Yangiqo‘rg‘on  In the days before overpopulation and “private property” made it difficult to travel without getting permission or a passport, humans were nomadic. They followed the seasons and, when they had “used up” the resources in a particular spot, they moved to another one, eventually colonizing the whole planet, including places where the snow never melts. As resources dwindled, they changed from colonizers to conquerors, often displacing or assimilating earlier cultures.

In the days before overpopulation and “private property” made it difficult to travel without getting permission or a passport, humans were nomadic. They followed the seasons and, when they had “used up” the resources in a particular spot, they moved to another one, eventually colonizing the whole planet, including places where the snow never melts. As resources dwindled, they changed from colonizers to conquerors, often displacing or assimilating earlier cultures.

From Watering Holes to Warfare

Lyrica tablets buy online The Mongols have long been known for their great equestrian skills, and for their ability to travel long distances through harsh climates. In the 13th century they were ambitious invaders, making repeated efforts to conquer China, parts of Russia, and even eastern Europe—their campaigns ranged over thousands of miles. In so doing, they came in contact with diverse cultures, sometimes absorbing their ideas, other times influencing or extinguishing them.

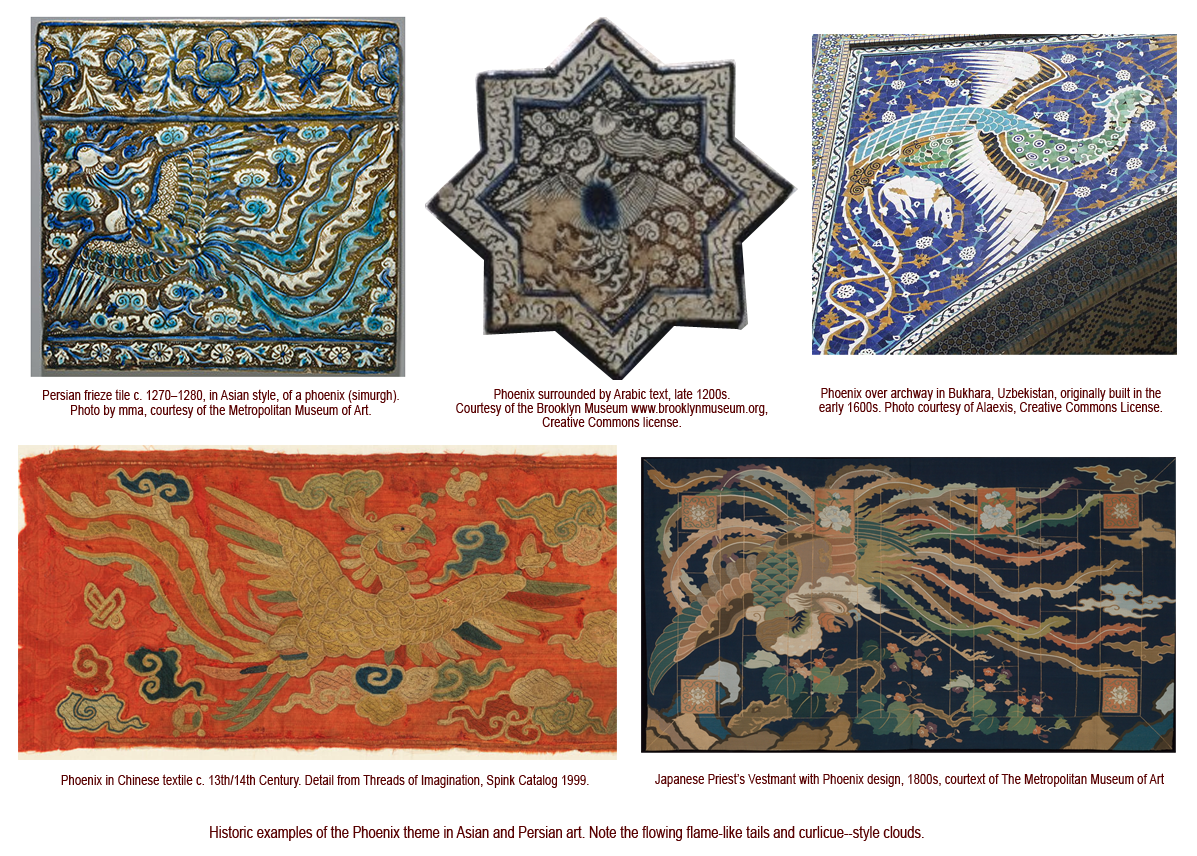

Some theorists say the Asian style of dragon that is especially prevalent in China, and to a lesser extent in Persia, was influenced by Mongolian art. I don’t have time to research this, it seems to me that 13th-century Mongolian art has a different look and different themes, and that a phoenix with flowing lines existed in early Japanese art and is found in Uzbekistan mosaic art, so perhaps it was indirect rather than direct influence that brought the extravagant flames and curlicue clouds to Persia in the middle ages. There were surely multiple lines of transmission, Mongol caravans with foreign goods, and new trade routes opened by Mongol incursions, but land-roving nomads were not the only visitors—seafaring traders were constantly moving goods between east and west and ship technology was constantly improving. Whatever the source, the ties with Asia are readily apparent in 13th-century Persian art.

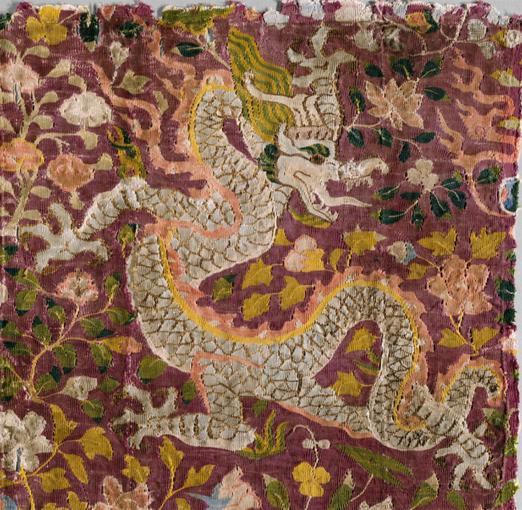

This fabulous textile art, created around the 11th or 12th century in east-central Asia, is thought to have been crafted by the Turkic Uyghur people, and might represent another route of transmission for east-to-west dragon imagery:

Note: Uyghur dragon textile was added a few hours after the blog was published. Note the tail snaking through the legs, a motif often seen in Mediterranean and western European drawings of lions. [Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.]

“In [book] illustration, new ideas and motifs were introduced into the repertoire of the Muslim artist, including an altered and more Chinese depiction of pictorial space, as well as motifs such as lotuses and peonies, cloud bands, and dragons and phoenixes.” –Suzan Yalman, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

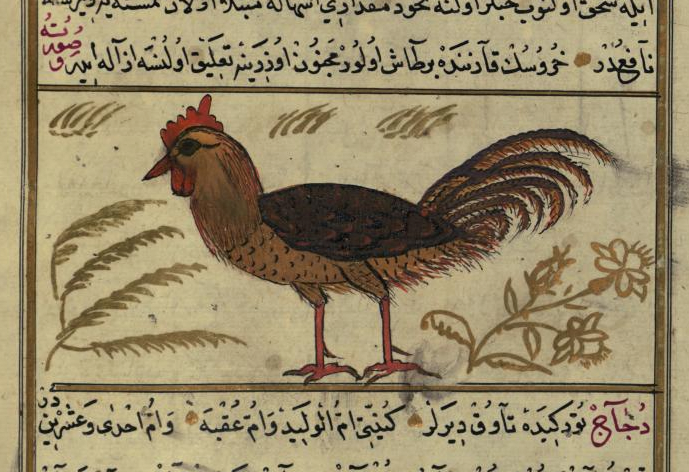

[Cockerel images added April 8, 2017] These examples from a group of Arabic manuscripts that were inspired by Al-Qazwini’s 13th-century bestiary, illustrate interesting differences in style:

Al-Qazwini’s bestiary, created around the mid-13th century, was reproduced in different versions. The top example of a cock from Walters MS 659 (1500s) is a traditional depiction, with no exaggeration in the landscape or details, the bottom one, from Bibliotèque Bordeau MS 1130, clearly shows eastern influence in the curlicue clouds, undulating landscape, and extravagant flame-like tail-feathers. The cock has almost been transformed into a phoenix.

Within the next few centuries, the eastern influence becomes even more apparent…

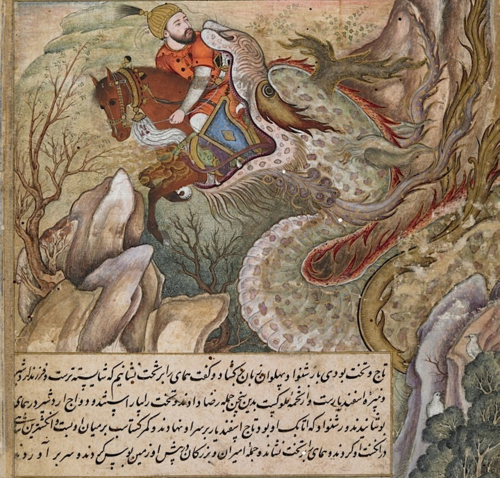

The British Library holds an illustrated Arabic romance of the adventures of the Persian King Darab, originally composed in the 12th century by Muhammad ibn Hasan Abu Tahir Tarsusi. The library’s copy dates to between c. 1580 to c. 1585, so it’s not as old as the phoenix tiles, but it shows a similar adaptation of eastern style in dragon art.

In this dramatic scene, Bahman and his horse are swallowed whole:

The nose looks like a camel, and it’s clearly a malevolent beast, but the tendrils on the lower jaw, the whiskers, eye-stripe, and mane are in the flamelike undulating style that is common to Chinese dragons.

[I had an example of an Asian-style dragon from western Europe that I found about three months ago but, unfortunately, despite a concerted hunt through my files, I can’t find it. If I do, I will upload it here.]

Summary

This is, in a sense, a follow-up to the post on the jongleurs, where the French illustrator used a different style to express itinerant performers (who may have been of eastern origin), but I also have a personal interest in Asian art and looked up some more specific examples that relate to cultural transmission to see when these particular styles were introduced to the Arabic world. Persia has had political ties with China at least since the 6th century (royalty intermarried), so there may be other examples, but unfortunately I can’t pursue all of them.

The images are interesting in their own right, so I decided to post them for Voynich researchers who may be curious about cultural influences between east and west.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2017 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved