how to buy gabapentin online Description

how to buy gabapentin online Description

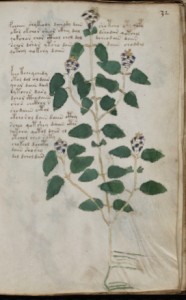

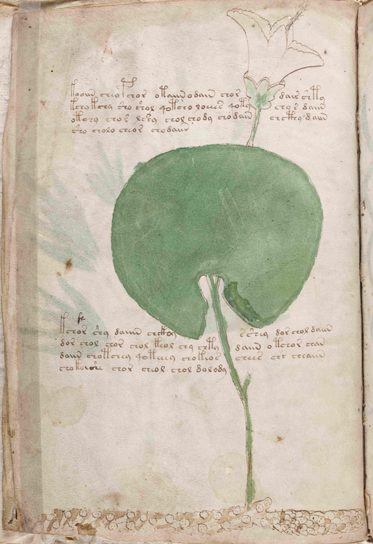

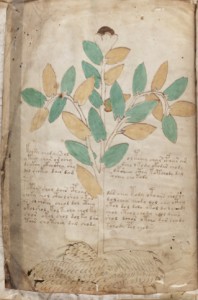

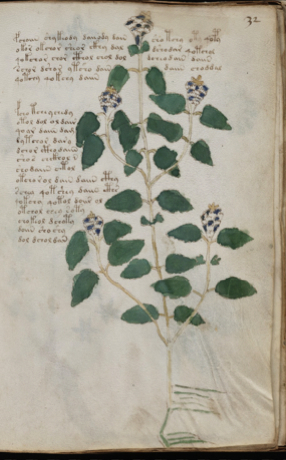

Plant 32r is an upright plant occupying a large portion of the page from bottom to top, interwoven with what appear to be two main blocks of text. The top “block” (assuming the lines on the left are associated with those on the right) is broken across the top of the plant.

The main plant colors are green leaves, brownish stems and blossoms, and alternating blue and clear for the scaly portion holding the blossoms.

The colors are somewhat crudely (hastily? impatiently?) applied but stay mostly within the lines. The blue, in particular, is “dabbed” with less concern for maintaining shape. This does not appear to be because of the space limitation since the blossoms, which are equally small, are more carefully rendered. Perhaps the blue pigment was drier and harder to spread smoothly.

Details

Leaves: Opposite, roughly between elliptical, cordate and deltate. There are smaller, somewhat irregular pairs under some of the larger leaves. The petioles are fairly short. The margins are serrated or irregular.

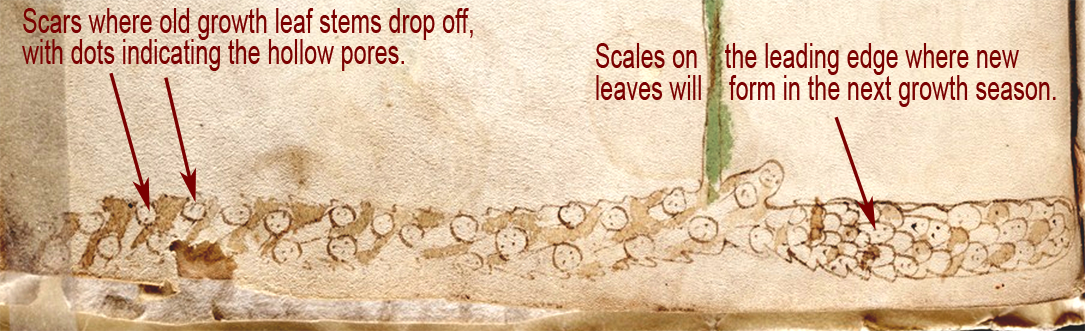

Flowers: Scaly/overlapping flower head, with a blossom protruding from the end that might have roughly three petals (or three petals visible from one side or may be trumpet-shaped).

Stems: Slender and regularly branching. Plant 32r shows a strong overall symmetry.

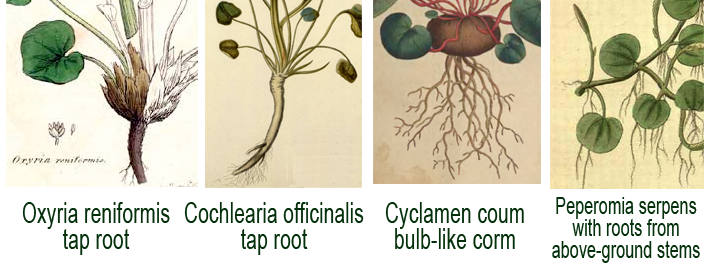

Roots: There appears to be a tap root with fine rather than thick tendrils, possibly asymmetric, or perhaps directional (more about this below). Most VM 408 plants are rendered in brown or brick red.

Prior Identification

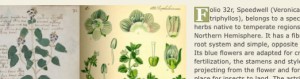

Edith Sherwood has identified this as Speedwell (Veronica triphyllos), but V. triphyllos differs from Plant 32 in a number of ways:

- V. triphyllos has small roughly palmate (somewhat digitate) leaf pairs at regular intervals along the stem (see illustration below), they are not the larger more elliptical/deltate leaves of Plant 32r.

- V. triphyllos blossoms don’t emerge out of a scaly head in the same manner as 324. There are sometimes clusters of leaves at the end of V. triphyllos stems, but the parts of the cluster are more distinctly separate and pointed than the heads of Plant 32r.

- The branching stems are not as symmetric as 32r.

- The pistils of V. triphyllos blossoms are quite prominent and might perhaps have been included by the VM illustrator.

- V. triphyllos stems and leaves are hairy and this too might have been included if the illustrator were trying to represent V. triphyllos.

I don’t see V. triphyllos as a good match for Plant 32r.

The palmate, somewhat digitate, leaves of Veronica triphyllos are distinctly different from Plant 32r. V. triphyllos is not as symmetrically branched as Plant 32r. The flower heads of V. triphyllos are more discrete and separate than the scaly heads of 32r.

Other Possibilities

Examples of possibile candidates for Plant 32r that more closely resemble the VM plant include the following:

Melampyrum cristatum (left) doesn’t appear to be close enough for consideration. The “scaly” section has long protruding tips and the leaves are too narrow but the pipe-shaped blossoms emerging from the end, the evenly branching stems and opposite leaf arrangement caught my eye. Melampyrum nemorosum (second left) has wider leaves but a more spiked and upright appearance.

Coridothymus capitatus is a medicinal plant mentioned in manuscripts like Materia Medica but the leaves are very small and not branched in the same way as 32r, and the blossoms at the tip of the flower head are more numerous than Plant 32r.

Thymus moroderi and Thymus serpyllum (middle right) are similar in structure to 32r, but the leaves are much smaller in proportion to the flower heads.

The Indian plant, Strobilanthes callosus, has some of the characteristics of 32r, but the blossoms are larger and are more numerous along the stems and the “scaliness” is not as prominent. Strobilanthes nutans is tempting, it has trumpet-shaped blossoms emerging from scaly flower heads and more closely matches 32r than S. callosus, but the branches tend to trail and the flower-heads to nod, while the Voynich plant appears to be upright. Strobilanthes dyerianus is more upright, but the blossoms protrude much farther than Plant 32r blossoms.

Possible Closer Matches

Agastache foeniculum (Anise Hyssop) and Agastache rugosa have longer, bushier flower heads and more pointed leaves than 32r. Agaste urticifolia (left, courtesy of Dcrjsr, Creative Commons), is a fairly close match for the 32r leaves, but it has more plume-like flower heads.

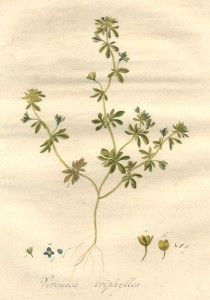

Stachys silvaticus (Hedge Woundwort, right) might be considered, it fits the overall proportions better than the previous examples. However, the leaves and flower heads are more tiered than the single flower head of 32r.

Plants of the mint family (Mentha), tend to have bushier flower heads than 32r and they rise in a tall spike, sometimes with several tiers. The leaf tips are a little more pointed than 32r.

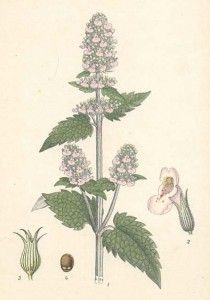

The blossoms of Nepeta cataria (Catmint, second right) tend to be more numerous than 32r but N. cataria might be worthy of consideration.

The Flower Heads

As far as matching the 32r flower head, lavender appears to be closer than most of the above.

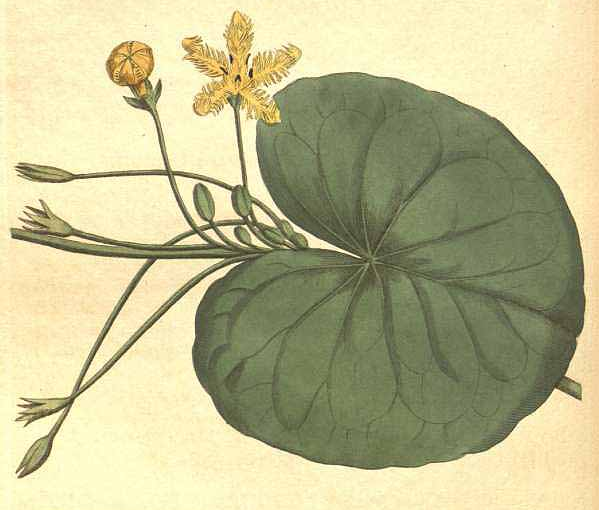

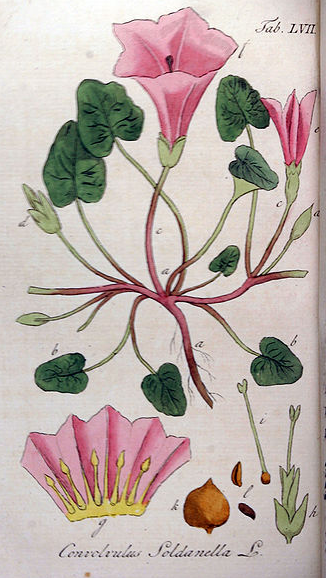

Lavender (middle) has flower heads simlar to 32r, with scaly, overlapping protrusions, and darker smaller blossoms within some of the “scales” and, in some varieties, like French lavender (right, Blackwell 1730s), a single larger blossom emerging from the end. However, the leaves are very narrow and linear, and not as distinctly opposite, compared to Plant 32r. The heads are a good match—the leaves are not.

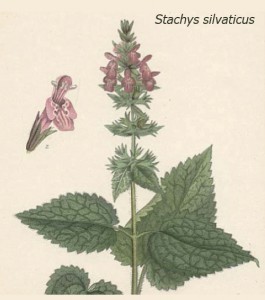

Which brings us to Prunella vulgaris, also known as Self-Heal—a plant with significant stature as a medicinal plant in the Middle Ages.

The leaf shape and general leaf-and-stem arrangement of P. vulgaris are a better match for Plant 32r, as are the scaled flower heads with protruding blossoms at the ends of the stems. The antique botanical print on the right shows tiny extra leaves reminiscent of the small leaves or bracts in Plant 32r. The distinction between the tiny florets within the “scales” and the end blossom is not as distinct as in the Blackwell French lavender illustration shown earlier, but overall, 32r is closer to Prunella or Catmint than to lavender.

Prunella (Self-Heal) is not an assured identification, but it is a step in the right direction and is a much closer match to 32r than Veronica triphyllos. Oddly, on a related note, Sherwood has identified Plant 14v as Stachys monnieri (Lamb’s Ear, Alpine Betony) even though the Voynich plant, 14v, is shown with large, heavily serrated, almost frond-like leaves, and S. monnieri has heads and leaves similar to Prunella. S. monnieri does have larger and more deeply serrated leaves, but even so, it is closer to 32r in general proportion of flowers to leaves than Plant 14v.

Roots

Also, as a point of interest, some of the old botanical illustrations (e.g., W. Baxter, 1837) show Prunella roots in a sideways orientation (left) and since the root tendrils come out of the root going down, it sometimes looks asymmetric like 32r (imagine it turned 90° as in the example in the middle so that it streams out of the main root to one side). This might be a stretch, to try to justify the arrangement of 32r roots but it’s something to think about. Some plants propagate by sending out root shoots to the side under the ground and perhaps this was the Voynich illustrator’s way of symbolizing it.

Summary

The above examples are not exhaustive. Each of the aforementioned plants may have relatives that more closely match Plant 32r and likely candidates from other species have been omitted for the sake of brevity, but it charts a path, based on details of the VM plant, to some of the more likely possibilities and explains why Sherwood’s choice of Veronica triphyllos seems unlikely.

Plant 32r Veronica triphyllos (Sherwood) Catmint Prunella

This is not a definitive identification but, for now, I’m leaning toward Prunella or one of its relatives as the inspiration for Plant 32r.

Posted by J.K. Petersen

Addendum: I’m not sure how the links to all the pictures disappeared (the pics were still visible in edit mode) but I have done my best to restore them to the originals. The article doesn’t make sense without them.