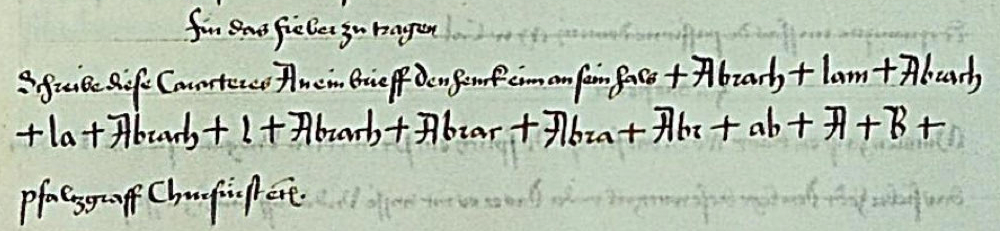

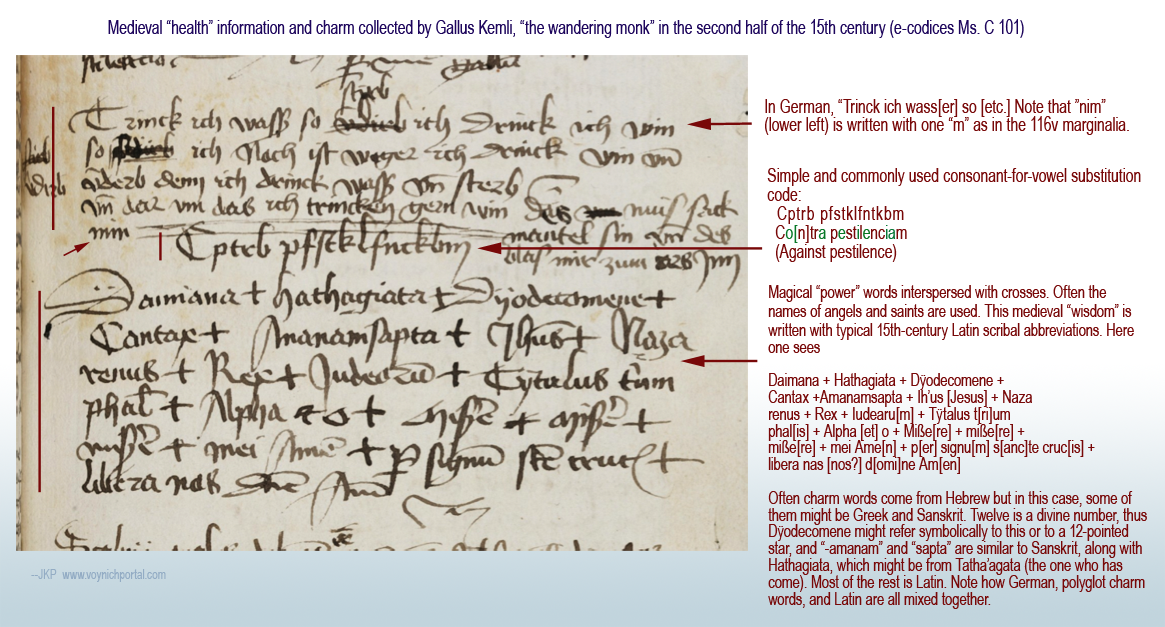

26 April 2016

Have you ever come across a single piece of information that gives everything a different perspective?

In 2008 and 2009, I obsessively perused every herbal manuscript I could find, going back to them again and again (you know you’ve been looking at too many herbals when you recognize crudely drawn plants without looking at the labels).

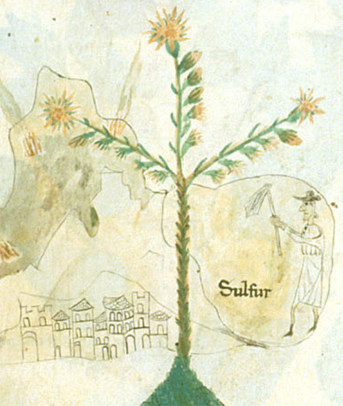

But I didn’t know this… I didn’t understand why some odd ingredients like storax (styrax), turpentine, and castoreum showed up together with leaves and roots, sometimes even interposed between plants that were not in alphabetical order. Not that it’s unusual to find these items in medicinal concoctions, but why these particular ingredients, and not the dozens of other commonly used non-leaf-or-root ingredients?

Castoreum

First let’s summarize castoreum, sometimes written as “castor”. Castoreum/Castore is not the same as the Ricinus (castor oil) plant. Ricinus is included in many herbal manuscripts—it’s an ancient medicinal plant—but castoreum or castore (castor) is an animal product that seems oddly out of place with sage, rosemary, and thyme. In fact, references to castoreum can be startling when you first see them as images of animals castrating themselves by biting off their testicles:

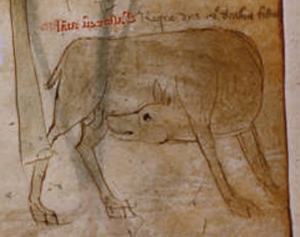

These animals can be stags or mythical animals, but a favorite is the poor beaver, which can look like anything, including a deer, fox, boar-with-webbed-feet, or dog-with-fat-tail to an anatomically correct (or sometimes anatomically bereaved) beaver:

As can be seen from these examples, the animal is recognized more by context (and labels) than the accuracy of the drawings. And their bizarre actions are not as masochistic as they seem. The beaver (shown here as a boar with webbed feet and scaly fat tail) knows the hunters are after his jewels and discards them in their path so he can escape with his life.

Testicles as ingredients are popular worldwide for a variety of medicinal concoctions and were featured in Galen’s famous Theriac recipe, originally developed as a cure for snake bites, but which was gradually marketed as a tonic and general panacea, one that remained popular for almost 2,000 years. Galen was a highly revered physician and scholar, and theriac became a staple in apothecary houses that catered to wealthy patrons.

I must have compartmentalized my familiarity with Galen and my reading of the contents of medieval herbals, because I never directly connected the herbals with theriac. I assumed castor and storax and a few other oddballs were in herbal manuscripts due to their general use in remedies but now I realize due to the express absence of other similar ingredients, they may have been there specifically because they were part of Galen’s famous remedy.

Snakes have long been used in medicinal concoctions and continued to be popular in the middle ages. There was a widely perpetuated myth that male vipers inseminated the females through their mouths and their young would later gnaw their way out of their mother’s body (right). This magical property probably elevated the status of viper as an ingredient in herbal remedies.

Snakes have many meanings in herbal manuscripts.

Often, they indicate a plant that is suitable for curing snake bites. Sometimes they refer to the name of a plant (like snake-weed) or the shape of a plant (e.g., one with a snake-like root). Snakes and dragons can mean a plant is toxic, the way we use a skull-and-crossbones symbol.

Often, they indicate a plant that is suitable for curing snake bites. Sometimes they refer to the name of a plant (like snake-weed) or the shape of a plant (e.g., one with a snake-like root). Snakes and dragons can mean a plant is toxic, the way we use a skull-and-crossbones symbol.

But… there are times when a snake appears on its own, and I now realize it might be because viper was an essential ingredient in Galen’s formula, along with castoreum.

Relevance to the VMS

In the Voynich Manuscript, there’s a distinct lack of non-root/leaf ingredients. There are no pictures of bitumen or chalciditis, nothing that looks like styrax or gum arabic in its chunky resinous form, and no gated balsam orchards, as there are in many other herbals. There are a few drawings that resemble snakes or worms, but they appear to be associated with the roots of plants, not with snake as an ingredient on its own. In other words, if there’s a strong Theriac influence in some of the other herbals, there’s no obvious corollary in the VMS.

But… is there a reference to castoreum?

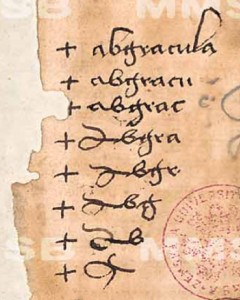

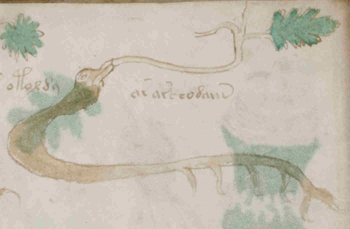

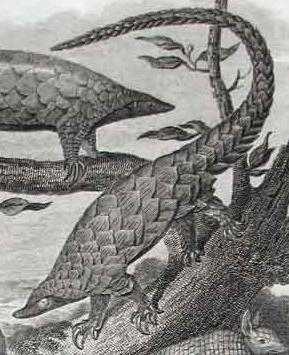

Is it possible the strange unidentifiable critter that looks like pangolin, sheep, and anteater all rolled into one could possibly be a beaver? Could the scales be like the scales sometimes depicted on medieval beaver’s tails but applied to the whole body in the VMS?

Is it possible the strange unidentifiable critter that looks like pangolin, sheep, and anteater all rolled into one could possibly be a beaver? Could the scales be like the scales sometimes depicted on medieval beaver’s tails but applied to the whole body in the VMS?

I honestly don’t think the VMS “pangolin” looks anything like a beaver, but neither do many of the other medieval depictions of beavers.

Maybe it’s a pangolin, an animal that curls up like an aardvark to protect itself, as has been put forth by quite a few Voynicheros (I like the idea of a pangolin), or a rain dragon, as been suggested on the Voynich forum, or if we glance back at a similar curled-animal drawing on another page…

Researchers have suggested the dead-looking creature on folio 79v might be a fleece (see earlier post). Could the pangolin-like creature also be a fleece? Could the curled-up creature be a pointy nosed lamb? Maybe those lines are nebuly lines after all and they indicate a dearly departed creature rather than a live one. The problem is it doesn’t look like the other sheep-like creatures in the VMS, it has a very sharp snout and the others are blunt, and the illustrator has made the back very scale-like—quite different from most sheeply creatures.

Researchers have suggested the dead-looking creature on folio 79v might be a fleece (see earlier post). Could the pangolin-like creature also be a fleece? Could the curled-up creature be a pointy nosed lamb? Maybe those lines are nebuly lines after all and they indicate a dearly departed creature rather than a live one. The problem is it doesn’t look like the other sheep-like creatures in the VMS, it has a very sharp snout and the others are blunt, and the illustrator has made the back very scale-like—quite different from most sheeply creatures.

Could it be a beaver about to become a beaveress or some other animal making a lifestyle change? Looking at the drawing by itself, it seems possible that it is eyeballing its undersides but… context should never be overlooked, and beneath the critter is a woman with a ring, and the animal seems to be suspended above her as though on a cloud or canopy. That seems an odd place for him to aim his teeth at his chestnuts.

Well what about the fleece idea? Golden fleece pendants were worn by members of the order of the Golden Fleece in the 15th century, but could a door above a meeting place have a suspended fleece as a sign? They have them now, but that doesn’t mean such a thing existed in the early 1400s. As usual, the way it’s presented in the VMS makes it hard to pin down.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2016 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

Postscript 9 Nov. 2019: I’ve been meaning to add this for months… it occurs to me from time-to-time that maybe the VMS illustrator used a minimum of visual exemplars (it wasn’t easy to get access to books in the Middle Ages) and perhaps was drawing from written (or verbal) sources.

Not all manuscripts were illustrated. In fact, many of them weren’t. For example, there are numerous medieval descriptions of plants and plant-based remedies that don’t have illustrations.

So, if the VMS illustrator heard (or read) the following passage in Revelation, how might they interpret an image of a fleece, sacrificial lamb, or lamb of God?

Worthy art thou to take the scroll, and to open the seals of it, because thou wast slain, and didst redeem us to God in thy blood, out of every tribe, and tongue, and people, and nation, and didst make us to our God kings and priests, and we shall reign upon the earth.

The reason I looked up this passage is because early depictions of Agus Dei (often called “the lamb of God”) generally show the lamb standing, while depictions from the latter 15th century and onward often show the lamb lying down or even sagging down. Is this due to a subtle difference in how passages such as “thou wast slain” were interpreted or iconographically represented?

Another thing I noticed while reading through the Bible was that the word “kid” is generally not used to distinguish a baby goat from a baby sheep. In fact, one passage in particular suggests the word “lamb” could refer to either a sheep or a goat:

…a lamb, a perfect one, a male, a son of a year, let be to you; from the sheep or from the goats ye do take. — Exodus 12

If the critter in the VMS were interpreted as Agnus Dei, then perhaps the idea that either a baby sheep or goat could be sacrificed might result in a drawing with appendages that could be ears… or perhaps could be horns.