Guatemala 9 April 2019

It was just pointed out to me by a Voynich researcher that Diane O’Donovan is writing about me on her blog. I took a look and was actually quite surprised that the information I posted in my columns blog was so badly misconstrued.

But before we get to that, let’s put this rumor to rest. Maybe someone was joking (if so, no hard feelings), but this was posted as an aside on O’Donovan’s blog…

(Some have suggested tongue-in-cheek that JKP is a pseudonym adopted by Rene Zandbergen who holds very similar views and is one of the very few who really has been constantly involved for ‘many years’ – but it’s just jeu d’esprit. I’m sure JKP is quite real).

D.N. O’Donovan, 9 April 2019

Yes, I am. And to anyone who may think the rumor is true, I’m not using a pseudonym—I blog with my real name. I’m assuming René Zandbergen is European. I am North American. There’s a rather long swim between us and we don’t know each other personally.

Also, as far as I know, Zandbergen has been involved with the VMS quite a bit longer than I have. I first learned of the manuscript through Edith Sherwood’s site sometime in late 2006 or early 2007. A Google search for Da Vinci brought me to her blog and then, in 2007, I noticed she had a lot of plant IDs, as well.

I’m very interested in plants, I love puzzles, I’m fascinated by history.

That’s how I got hooked on the VMS. I wanted to solve it and it’s a perfect fit with my interests. I never planned to blog about it (my friends talked me into starting a blog, they kept insisting I had something to offer) and I’m still not sure a blog was a good idea (it takes time away from research) but in the process of blogging and joining the Voynich forum, I have met some beautiful minds, so it’s probably worth the sacrifice of time.

Now, to other matters…

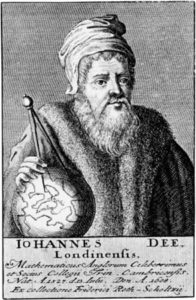

You know what. I was going to quote some of the “twists” on O’Donovan’s site and respond to them point-by-point, but I have changed my mind. There are too many. It would take too long. Plus, she chose to nullify the fact that Jacobi de Tepenecz was educated in Jesuit schools, administrated a Jesuit college, died in the hands of Jesuits, and left his estate to the Jesuits by declaring that he, “does not seem to have been an ordained member of any Jesuit community”.

If it walks like a duck and talks like a duck, then I don’t think it needs to be http://e17arttrail.co.uk/index.php?page=101 ordained as a duck to be included in general statements about the Jesuit community. My blog was not about Jacobi, it was about the column text.

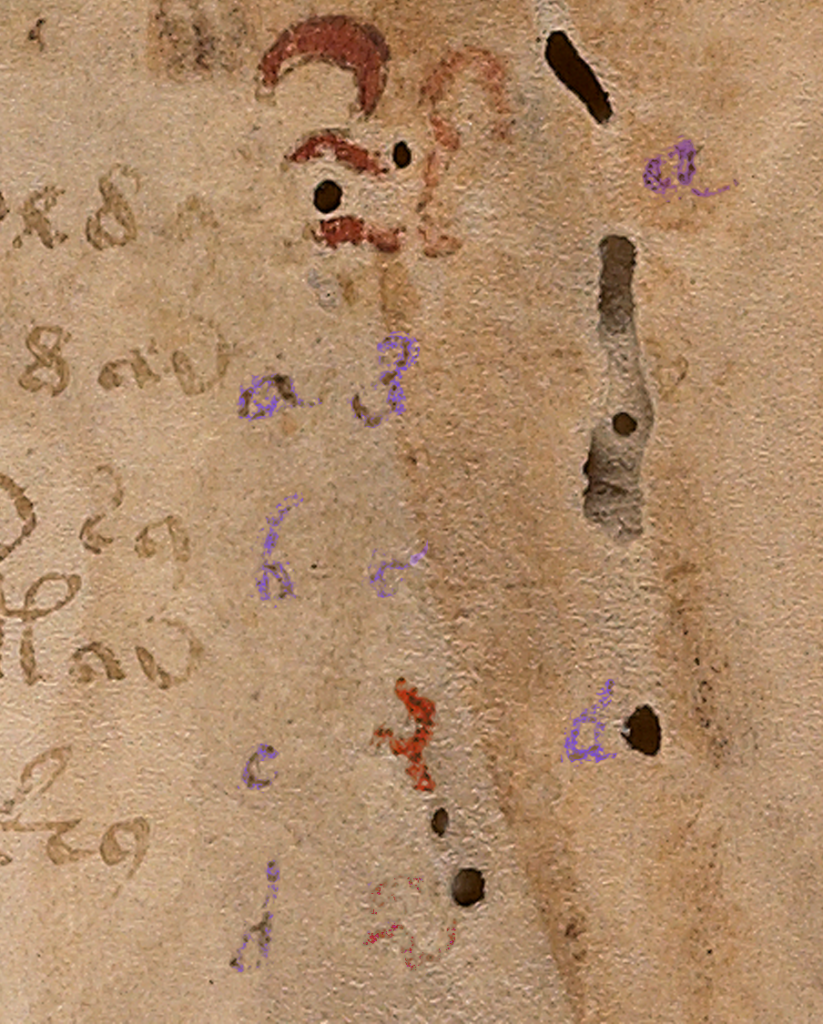

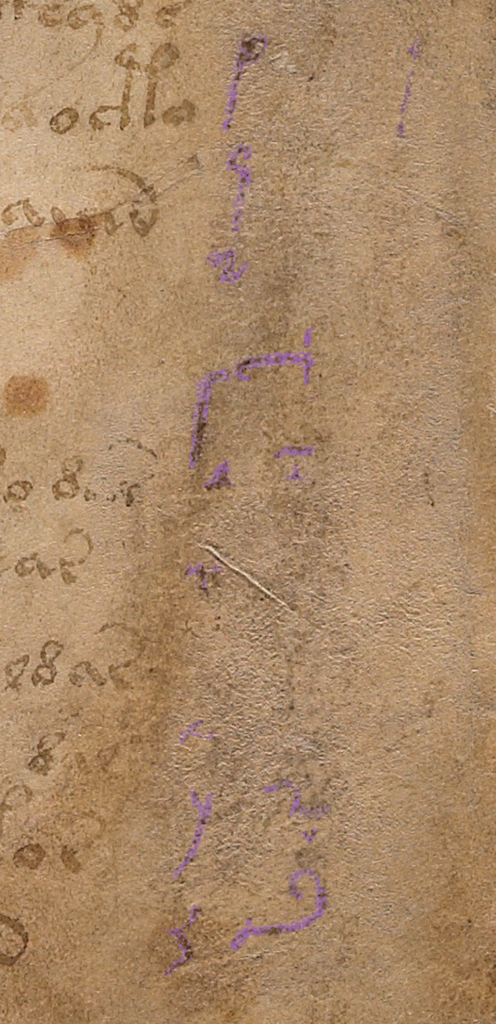

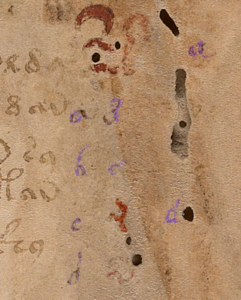

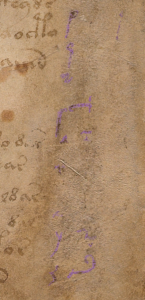

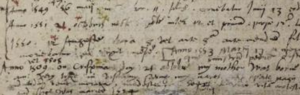

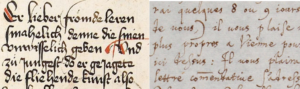

De Tepenecz Signature

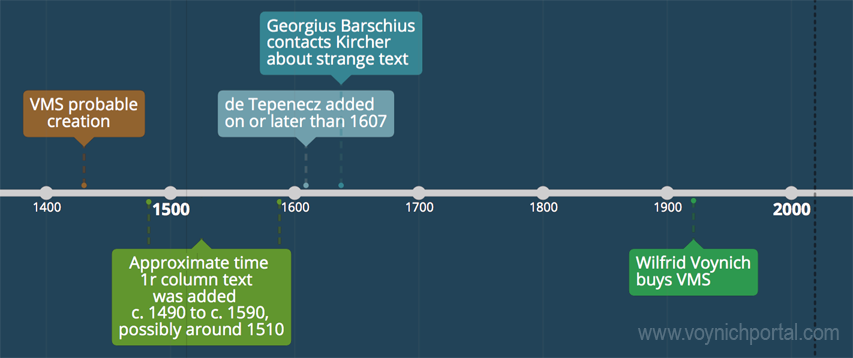

I’m also not sure why she posted a recreation of Jacobi de Tepenecz’s signature in connection with her comments about my study of the column text. It’s different handwriting. It should be in a separate section, not conflated with my column-text blog.

I didn’t discuss the signature because there might be a time gap between the writing of the column text and the addition of the signature at the bottom of folio 1r. We don’t know yet. I don’t have enough information on the signature to blog about it, and I think it’s premature to imply an association between them.

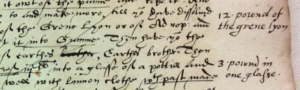

In my opinion there’s not enough research yet to draw any conclusions about Jacobi’s signature. In the scant examples that people have kindly posted on the Web (and which were probably difficult to find), the legal signature doesn’t match the other signatures and the other signatures almost look like two different hands, as though they were greatly separated in time, or perhaps because his name was added by someone else’s hand?

If you are interested in VMS provenance related to Jacobi de Tepenecz, Anton has been posting some very good research on the Wroblicionim annotations on some of Jacobi’s books on the Voynich.ninja forum. This enlightening detective work is slowly but surely helping to round out the picture.

Suffice it to say that in my previous blog, I presented needle-in-a-haystack work-in-progress to help fill out some of the missing corners of Voynich history, and presented it as simply as possible, and was not trying to change or misrepresent the manuscript’s provenance, as O’Donovan has implied.

J.K. Petersen

© copyright 2019 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved.