Cesare da Cesto copy of a painting by Leonardo da Vinci showing Leda, Zeus in the guise of a swan, and the two eggs that hatched from their union—one with the sisters, the other with the brothers, Castor and Pollux.

The constellation Gemini is traditionally represented by male twins who were born to the legendary Leda, daughter of King Thestius.

The god Zeus desired Leda, but she was married to the Spartan King, so he came to her in the form of a swan that was fleeing an attacking eagle, thus contriving to fall into her protective arms with the intent to seduce her. In the process he impregnated her and she bore two sets of twins.

In one version, the male twins Castor and Pollux were fraternal twins, one born of King Tyndareus, the other of Zeus. In another version, two eggs result from the illicit union—one hatches into Castor and Pollux, the other into their sisters.

The twins were close, as many twins are, so when Castor was killed, his brother Pollux was devastated and begged Zeus to reunite them. To soothe the twin’s grief and perhaps to atone for his adulterous sin, Zeus turned them into the constellation Gemini, so they could be together forever.

Based on this legend, Greco-Roman images of Gemini typically show male twins closely associated, side-by-side.

The VMS Interpretation of Gemini

In contrast, the Voynich Manuscript Gemini shows a man and a woman clasping hands crossways (a posture that was noted by a number of Voynich researchers) in the center of a figural wheel.

Let’s look more closely at the details…

Let’s look more closely at the details…

The man wears a traditional belted pleated tunic, boots, and the larger floppier medieval version of a beret. The tunic and hat are painted green.

The woman is decked out in a flowing blue robe with wide sleeves with a scalloped edge (probably trimmed with ruffles or lace). An undergarment or shirt can be seen poking out past the outer sleeves. She has long hair and a blue band across her forehead. It’s interesting that the illustrator included this level of detail in the boots and sleeves considering this drawing is very small.

I wondered whether the VMS image were unusual or whether Gemini traditions changed during the middle ages, so I looked through hundreds of zodiac cycles to study the pattern of evolution.

Traditional Depictions

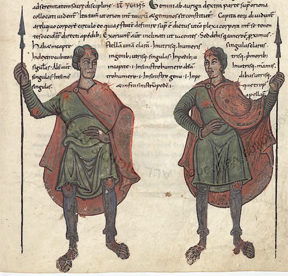

In ancient and early medieval zodiacs, male twins are usually shown side-by-side with their arms around each other’s backs as in this Mithraic Gemini (right) from the 2nd century CE (now in the Modena Museum). From about the 9th century, the twins are sometimes shown standing side-by-side holding weapons, musical instruments, or symbolic items. Ancient Geminis were usually nude or wearing scanty togas. The ones in Jewish synagogues were usually clothed.

In ancient and early medieval zodiacs, male twins are usually shown side-by-side with their arms around each other’s backs as in this Mithraic Gemini (right) from the 2nd century CE (now in the Modena Museum). From about the 9th century, the twins are sometimes shown standing side-by-side holding weapons, musical instruments, or symbolic items. Ancient Geminis were usually nude or wearing scanty togas. The ones in Jewish synagogues were usually clothed.

In Persia, we see a variety of cultural influences.

In Persia, we see a variety of cultural influences.

Some followed the Greco-Roman style of side-by-side twins and some depicted the twins with one body and two heads as in this 11th century “zodiac man” Gemini on the left. The Codex Vindobonensis (Austria? c. 13th C) has a similar image but the twins wear Phrygian caps rather than crowns. It would be easy to assume the two-headed Gemini was based on Janus, the ancient god who symbolized the beginning and the end and was often shown with two heads, but it doesn’t fit well with the legend of Castor and Pollux or the culture that created this variation, so it’s possible it’s based on something else…

The two-headed Gemini is mostly seen in Hebrew manuscripts or those written by Jews in other languages, so it may have descended from the mosaics in the Jewish synagogues. In the Beit Alpha mosaic (6th C), for example, Gemini is two figures clothed in one garment. Even though each twin has two legs and two arms, it’s an image that could easily be interpreted as conjoined twins because we can’t see what’s going on under the shared clothing.

The two-headed Gemini is mostly seen in Hebrew manuscripts or those written by Jews in other languages, so it may have descended from the mosaics in the Jewish synagogues. In the Beit Alpha mosaic (6th C), for example, Gemini is two figures clothed in one garment. Even though each twin has two legs and two arms, it’s an image that could easily be interpreted as conjoined twins because we can’t see what’s going on under the shared clothing.

Gemini in the Middle Years

In other cultures, the Greco-Roman tradition of nude male twins (sometimes with and sometimes without genitalia) and, in some cases, a nude male Virgo, continued for a few more centuries. The 11th-century image on the left is a Frankish zodiac that retains Roman influence.

In other cultures, the Greco-Roman tradition of nude male twins (sometimes with and sometimes without genitalia) and, in some cases, a nude male Virgo, continued for a few more centuries. The 11th-century image on the left is a Frankish zodiac that retains Roman influence.

So when did the creators of manuscripts decide to go their own way and clothe the twins?

One of the earlier examples of the break with tradition is Vatican Reg. Lat. 123, created at the St. Maria Rivipulli monastery c. 1056. The influence is clearly Greco-Roman, but Virgo and Gemini are fully clothed (right), thus imposing Christian modesty on legendary Pagan characters. Note that they also separated the twins with a wider space. The addition of clothing was picked up by some of the English and Frankish illuminators at around the same time, as in Arundel 60 and Royal 13 A XI, but some continued to depict the characters nude.

One of the earlier examples of the break with tradition is Vatican Reg. Lat. 123, created at the St. Maria Rivipulli monastery c. 1056. The influence is clearly Greco-Roman, but Virgo and Gemini are fully clothed (right), thus imposing Christian modesty on legendary Pagan characters. Note that they also separated the twins with a wider space. The addition of clothing was picked up by some of the English and Frankish illuminators at around the same time, as in Arundel 60 and Royal 13 A XI, but some continued to depict the characters nude.

Some illuminators compromised by drawing mostly naked twins in scanty breech cloths (e.g., Egerton 1139, c. 1130s CE) or, in later years, by hiding them behind a bush (the green kind).

In the Hunterian Psalter (left), the twins are fully clothed but display a further innovation… they share a common shield—an iconic representation of their commitment to stick together to defend one another as brothers. This detail is important because the shield becomes widely adopted later, first in England, then in other areas. Note also that the clothing is becoming more local than Roman.

One of the transitional zodiacs is the Stammheim Missal (Getty Ms 64, c. 1170s) which includes a mixture of Greco-Roman and biblical elements. Virgo is female, as in Jewish and Christian zodiacs, Sagittarius is a satyr with an animal head (Jewish), and Capricorn is a Roman-style sea-goat. I thought Gemini might be male-female, but on looking at a higher-resolution image, it appears that both are male.

Gemini Gender Reassigment

One of the more significant changes in Gemini is the introduction of male-female twins, and one of the earliest unambiguous examples is the c. 1300s Claricia Psalter (right). Why alter a tradition that had remained virtually unbroken for more than 1,000 years? Maybe the female twin was introduced because this psalter was created by nuns—most scriptoria were staffed by males.

One of the more significant changes in Gemini is the introduction of male-female twins, and one of the earliest unambiguous examples is the c. 1300s Claricia Psalter (right). Why alter a tradition that had remained virtually unbroken for more than 1,000 years? Maybe the female twin was introduced because this psalter was created by nuns—most scriptoria were staffed by males.

Hildegard von Bingen’s drawing of Gemini (c. 1200) might be male-female, but it’s hard to tell. There are definite differences between the twins, but the drawing is small and somewhat ambiguous. I suspect it’s male-male.

The Shared Shield

Coming back to the shield, the Henry of Blois psalter is an Anglo-Norman manuscript created in England in the late 12th or early 13th century that includes two seminude twins, probably both male, leaning toward each other over a shield-like central embellishment. Its identity as a shield is less definite than later manuscripts. If you separate out the blue background and orange cloaks, it’s unusually narrow, more like a decorative element than a shield, but it may have been perceived as a shield because shields became popular from this point on.

Coming back to the shield, the Henry of Blois psalter is an Anglo-Norman manuscript created in England in the late 12th or early 13th century that includes two seminude twins, probably both male, leaning toward each other over a shield-like central embellishment. Its identity as a shield is less definite than later manuscripts. If you separate out the blue background and orange cloaks, it’s unusually narrow, more like a decorative element than a shield, but it may have been perceived as a shield because shields became popular from this point on.

The introduction of the shield allowed the nude tradition to continue without offending people of more modest sensibilities, as in the Hours of the Virgin (right), which interestingly shows conjoined twins (as does Trinity B-11-7 from c. 1400). Morgan Ms M.153 and Ms M.283 (France) follow the same illustrative tradition. Note that the twins are still typically male. You may also have noticed from the examples (and as mentioned in the previous blog on Libra) that medieval zodiacs are frequently enclosed within circles.

The introduction of the shield allowed the nude tradition to continue without offending people of more modest sensibilities, as in the Hours of the Virgin (right), which interestingly shows conjoined twins (as does Trinity B-11-7 from c. 1400). Morgan Ms M.153 and Ms M.283 (France) follow the same illustrative tradition. Note that the twins are still typically male. You may also have noticed from the examples (and as mentioned in the previous blog on Libra) that medieval zodiacs are frequently enclosed within circles.

Diverging from Tradition

The Shaftesbury Psalter (England, c. 1237) is similar to the previous three in many ways, but introduces a new motif for the twins. They’re not standing or holding weapons, they’re not hiding behind cloaks or shields. Instead they are clasping each other by the shoulders and floating together in a boat with a nordic-style figure-head. The sign for Capricorn is also unique from other zodiacs. It is bright blue, has been liberated from his fish-tail, and is marching and blowing a horn, a theme possibly inspired by marginal drawings in manuscripts that don’t include zodiacs.

The Shaftesbury Psalter (England, c. 1237) is similar to the previous three in many ways, but introduces a new motif for the twins. They’re not standing or holding weapons, they’re not hiding behind cloaks or shields. Instead they are clasping each other by the shoulders and floating together in a boat with a nordic-style figure-head. The sign for Capricorn is also unique from other zodiacs. It is bright blue, has been liberated from his fish-tail, and is marching and blowing a horn, a theme possibly inspired by marginal drawings in manuscripts that don’t include zodiacs.

The Male-Female Theme Goes Mainstream

By the mid-to-late 13th century, male-female pairs show up independently of the Claricia Psalter. The Amiens Cathedral, near the north coast of France, has a stone-carved Gemini of a man and woman holding hands and gazing at each other with warm affection, exemplifying the break from Roman tradition. Closer to the source of the Claricia Psalter (and perhaps influenced by it) is Morgan Ms M.280 (right) with male and female clasping one another.

By the mid-to-late 13th century, male-female pairs show up independently of the Claricia Psalter. The Amiens Cathedral, near the north coast of France, has a stone-carved Gemini of a man and woman holding hands and gazing at each other with warm affection, exemplifying the break from Roman tradition. Closer to the source of the Claricia Psalter (and perhaps influenced by it) is Morgan Ms M.280 (right) with male and female clasping one another.

What is not known about these early examples of male-female Geminis is whether illustrators had lost the connection to the legend of Castor and Pollux or if this was a deliberate choice to create their own zodiac traditions at a time when the idea of “courtly love” (medieval chivalry) was gaining popularity.

What is not known about these early examples of male-female Geminis is whether illustrators had lost the connection to the legend of Castor and Pollux or if this was a deliberate choice to create their own zodiac traditions at a time when the idea of “courtly love” (medieval chivalry) was gaining popularity.

In Royal 2 B II, a French Psalter, the figures aren’t just sharing a filial hug, they are kissing one another, in a manuscript created for a nun. After the mid-13th century, many manuscripts include a shield (usually with male twins) or male-female twins clasping one another or holding hands.

Hebrew Traditions

The Michael Mahzor (right), a Hebrew document from the mid-13th century, has a unique interpretation of the twins. They are drawn with animal heads and face away from one another, with no physical contact. Virgo is also drawn with an animal head, possibly due to the prohibition against graven images.

The Michael Mahzor (right), a Hebrew document from the mid-13th century, has a unique interpretation of the twins. They are drawn with animal heads and face away from one another, with no physical contact. Virgo is also drawn with an animal head, possibly due to the prohibition against graven images.

The Schocken Italian Mahzor, Add 22413 mahzor (c. 1322, lower right), and Oxford Mahzor (1342) similarly have animal heads, but the figures face one another.

The Add. 26896 mahzor (c. 1310s) harks back to older versions with conjoined twins but with animal heads (rather than human heads wearing crowns, as in the Persian Gemini previously shown).

The Dresden Mazhor from 1290 contrasts with the previous examples by having male and female figures with human heads facing one another.

Innovations in the 13th Century

The twins-in-a-boat was an early 13th-century English creation. Half a century later, in Switzerland, there was another creative variation in which the twins (who may be male and female) are shown in a bathtub (or a wine-stomping barrel). The other zodiac signs in the Swiss manuscript follow traditional patterns for the region, so it’s not clear why the bathtub was added. The bathtub shows up again about a decade later in a manuscript from Liège that follows some of the conventions of central Europe.

The twins-in-a-boat was an early 13th-century English creation. Half a century later, in Switzerland, there was another creative variation in which the twins (who may be male and female) are shown in a bathtub (or a wine-stomping barrel). The other zodiac signs in the Swiss manuscript follow traditional patterns for the region, so it’s not clear why the bathtub was added. The bathtub shows up again about a decade later in a manuscript from Liège that follows some of the conventions of central Europe.

England diverged from tradition again in the early 1300s by drawing the Gemini twins and Virgo as merpersons. Around the same time, a manuscript from Bologna included two sets of twins (possibly because Leda’s swan eggs produced twin boys and twin girls).

Persian Manuscripts

Persian astronomical/astrological manuscripts before the 11th century typically didn’t include a full zodiac but, by the mid-1300s (right), we see male twins with a conjoined fish tail facing one another, holding a head on a staff. Later manuscripts from the 15th century had male conjoined twins sitting crosslegged in eastern-style dress. Clearly the VMS Gemini is not based on this model.

before the 11th century typically didn’t include a full zodiac but, by the mid-1300s (right), we see male twins with a conjoined fish tail facing one another, holding a head on a staff. Later manuscripts from the 15th century had male conjoined twins sitting crosslegged in eastern-style dress. Clearly the VMS Gemini is not based on this model.

The Exception Becomes the Norm

By the 14th century, male-female zodiacs were common in the Anglo-Frankish and Germanic regions (which included most of the Holy Roman Empire, including northern Italy down to Rome and Venice).

By the 14th century, male-female zodiacs were common in the Anglo-Frankish and Germanic regions (which included most of the Holy Roman Empire, including northern Italy down to Rome and Venice).

Not all illustrators made the switch, however. In Tractatus de sphaera (c. 1327), the traditional nude male twins and Virgo with wings are seen.

A Catalan breviary differs from most zodiacs by illustrating Gemini as a pair of male warriors going at each other in a very unbrotherly way.

Zeroing in on the VMS

By the mid-1300s, Gemini twins start to more closely resemble the VMS Gemini.

By the mid-1300s, Gemini twins start to more closely resemble the VMS Gemini.

There were still many Geminis with shields in France and England, and zodiacs from Genoa (c. 1365) and Padua (c. 1378) that include a traditional pair of nude males, but Germanic manuscripts (especially Swiss, German, and a few of the Czech zodiacs), and a few of the English and French manuscripts, illustrate the idea of “courtly/chivalric love” and are possible precedents. Getty Ms 34 (1395) takes it one step further and has the twins in an unusually tight hug.

Small Stylistic Changes in the 15th Century

Around 1418 there was a re-emergence of nude male twins in both France and Germany, but rather than drawing them like Roman warriors or gods, they look more like young men and boys. A manuscript from Germany takes a different approach and casts the twins as Adam and Eve holding branches against their groins.

The poses change as well. Rather than clasping one hand or hugging each other’s backs, the figures are commonly clasping arms at the elbow or stretching their arms so their hands are on each other’s ribs. To date, I have not found one in which the arms reach across each other as in the VMS.

By the 1440s, modesty again takes hold in parts of France, and the twins hide behind bushes. In one case conjoined twins hide their shared groin behind an oversized fig leaf (BNF Latin 924) and then the trend swings again toward depicting the twins as completely nude (and not hiding behind anything). In this way the French manuscripts generally differ from the VMS, which shows the twins modestly clothed with high necklines.

By the 1440s, modesty again takes hold in parts of France, and the twins hide behind bushes. In one case conjoined twins hide their shared groin behind an oversized fig leaf (BNF Latin 924) and then the trend swings again toward depicting the twins as completely nude (and not hiding behind anything). In this way the French manuscripts generally differ from the VMS, which shows the twins modestly clothed with high necklines.

While central and northern Europe were developing their own styles, the illuminators in southern Italy retained many of the Roman traditions into the 15th century, including togas, two-legged Taurus, and Virgo with wings (e.g., Codex Bodmer 7 from Naples). A 15th-century zodiac by Cristoforo de Predis of Milan follows the central-European models except that the nude male twins stand back-to-back.

Summary

The early 15th-century image on the right is not specifically from a zodiac cycle, but I’m posting it because it includes a clasping couple with text around the circle, reminiscent of the VMS, and helps to remind us that the VMS illustrator may have consulted non-zodiacal sources, as well.

The early 15th-century image on the right is not specifically from a zodiac cycle, but I’m posting it because it includes a clasping couple with text around the circle, reminiscent of the VMS, and helps to remind us that the VMS illustrator may have consulted non-zodiacal sources, as well.

It can be seen from the examples that the VMS Gemini bears little resemblance to the Persian, traditional Jewish, or southern Italian zodiacs, and only slightly resembles those from France and Spain. Like Sagittarius with a crossbow, the lizard/dragon Scorpio, and Libra without a figure, the ones that most nearly resemble the VMS in terms of subject matter, pose, and painting style, are the zodiac Geminis from Germanic Europe (the Holy Roman Empire).

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2016 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

I think there are plenty of reasons to look outside of the zodiac tradition for the imagery, as you demonstrate again here.

The sex changes of constellations is an intriguing matter as well, that I’ve been looking into lately. Also many Voynich nymphs show evidence of having been made female, and many look androgynous.

I wonder whether the custom of depicting such male figures without genitals (Ken doll look) is to be seen as an in between stage, that allowed later copyists to fill in the gender as they wished. In one of my last posts, I show an image of the constellation “Hercules” with clear female genitalia, obviously adapted from a “Ken doll” look.

Anyway, so far I haven’t found any image of a pair with crossed arms, though in my opinion certain Roman and Medieval wedding/betrothal images come close.

Hello, off topic comments: your blog posts are well researched (even if I don’t always agree with everything), congratulations.

I would be interested to read your take on f77v : at the top we see a woman on the left, a man on the right and the four elements in that order : air water fire earth.

It is tempting to try and investigate this in details (in particular, which languages, if any, show similarities with the voynichese there, and whether the four words appear elsewhere on that page, etc.).

Best wishes.

some_reader007 wrote: “I would be interested to read your take on f77v : at the top we see a woman on the left, a man on the right and the four elements in that order : air water fire earth.”

You bring up an interesting part of the manuscript.

When I look at an image like the one at the top of f77v I will, of course, be reminded of the basic elements because it’s a medieval drawing and people in those days believed everything was composed of simple building blocks, but… I don’t assume these images are air water fire earth in that order or in any order because I don’t want to make too many assumptions too soon. When I look at this drawing, I don’t see four “pipes”, I see five, each with some text nearby that *might* be a label.

Even if we could establish for certain that this drawing represents basic elements, different cultures have different interpretations of what they are.

Some cultures believe there are five elements: air water fire earth and aether, and this could fit the VMS imagery quite well since aether was considered the substance of the universe or, in alchemy, the spiritual being (which might be represented by the central pipe that has no physical substances poofing out of it). Some cultures include wood, others include metal.

Since the imagery looks very biological (a bit like arteries), it may have nothing to do with air water fire earth. Maybe these are references to phlegm, blood, black bile, and yellow bile, the basic building blocks of physical anatomy that were used by doctors to diagnose illnesses and prescribe treatments.

It seems that the simplest answer is that they are air water fire earth (and maybe the fifth one is aether or spirit) but then you have to wonder why something so banal and generally accepted would be represented in such an enigmatic way.

Thank you for that answer, and your caution is very commendable (to make a correction, I meant f77r but you understood).

To answer your last point, isn’t precisely the aim of the WM to obfuscate banal topics? If so, this page could be important to identify some words. The ‘o’ at the beginning of words is reminiscent of Portuguese for ‘the’ (masculine words) and Spanish ‘él’, so we might be seeing here ‘theair’ ‘thewater’ ‘thefire’ ‘theearth’.

Another interesting topic, totally different, is that of repairs (for example on f82), could one come up with clues here? For instance do the loose holes mean they have been made while the sheepskin was fresh? And is the size of the needle holes indicative of anything (location, era)? In all other manuscripts that I have seen repairs are almost always tidier, usually with still the thread in.

“To answer your last point, isn’t precisely the aim of the WM to obfuscate banal topics?”

If the text is written by the same person who created the drawings, this might be true. Herbals were not in the same secretive categories as alchemical, magical, or esoteric manuscripts, so if the VMS plant section is an herbal compendium, it seems the only reason to use unreadable text would be for the scribe’s convenience (e.g., to phonetically spell a language that doesn’t have a written script). Why hide it?

However, if the text were written by someone other than the illustrator or if the text is not related to the illustrations in any way (if it were sensitive political commentary, for example) the topics may not be banal. For the present, I prefer to assume there is some relationship between text and illustrations as there are clues pointing in this direction, but that brings us back to your comment—there’s no obvious reason to obfuscate herbal, zodiacal, or medical texts. Books on these topics may have been kept close at hand (by apothecaries, astrologers, and doctors who valued them as trade secrets) but one doesn’t usually see them enciphered.

“If so, this page could be important to identify some words. The ‘o’ at the beginning of words is reminiscent of Portuguese for ‘the’ (masculine words) and Spanish ‘él’, so we might be seeing here ‘theair’ ‘thewater’ ‘thefire’ ‘the earth’.”

I’ve long wondered whether the “o” is a marker or modifier. There are many languages that designate gender or a property of a word (e.g., that it is a noun or other grammatical element) with a letter at the beginning. This would work equally well for natural or constructed languages. I’ve also wondered whether some of them are nulls.

Assuming they are labels, and that the “o” is meaningful rather than a null character, labels might hold important clues. Labels next to imagery are usually harder to obfuscate than larger blocks of text because they are inherently short and specific.

But….

It has long been my opinion that the word-tokens in the VMS are atypically short and that there are far more 1, 2, and 4-letter glyph-groups in the main text than are usually acknowledged. If the VMS is a natural language rather than a constructed language, then it might be an abjad (with vowels omitted) or text that has been broken into smaller pieces before encoding it.

I didn’t blog about this back when I first noticed it (in 2009) because I was looking for evidence that this concept had precedents in the 15th century or earlier. Just because words CAN be broken into smaller units, doesn’t mean people did it. In Feb. 2016, when Pal. Germ 597 was mentioned by other researchers as containing a cipher, I took a look and noticed a large block of text (a page and a half) was broken into smaller units.

For example the word “decoratur” is written as “de co ra tur” and “scolastica” is written “sco las ti ca”. Since the document discusses alchemy (sulphur, mercury, etc.), is partially encoded, and the section that is broken up includes a lot of social name dropping, it’s doubtful that it’s intended to teach phonics. I assume the text has been deconstructed in preparation for encipherment.

Since deconstructed text did exist in cipher-related 15th-century manuscripts, one has to consider that the spaces between words in the VMS might be artificial, as well. Even if they are not, the spaces between the labels might be artificial and the syllables might have to be reconnected with their mates before they can be read or, alternately, they might be intended as a sentence rather than as individual labels.