“…some symbols in the Voynich Codex show similarities to letters found in sixteenth century codices from New Spain (Tucker and Talbert 2013; Comegys 2013) particularly the Codex Osuna (Valderrama 1600; Chávez Orozco 1947).” —Janick and Tucker, Aug. 2018

The authors are talking about shapes that roughly resemble EVA-k and EVA-t. The following statement is much more surprising:

“We thus conclude that the author of the Voynich Codex made up his syllabary/alphabet, and the letters were borrowed from contemporary post-Conquest MesoAmerican manuscripts such as the Codex Osuma.”

In scholarly circles, “conclude” is a strong word—a word that needs to be backed up with solid evidence. Unfortunately, I find this conclusion highly questionable. The examples the authors use in their arguments are conventions that originated in Old World Latin scripts long before the 16th century. How can one use Old World scribal conventions to argue for a New World conclusion?

Is There a Preponderance of Evidence to Support the Conclusion?

Perhaps the authors felt that if the glyph shapes are taken together with botanical and biological identifications, there is enough evidence to support a New World origin, but the botanical and biological identifications of Tucker, Talbert, Janick, and Flaherty are highly questionable, as well. If you haven’t been following this discussion, then at least scan-read the previous blogs:

- Mistaken botanical and biological identifications?

- Is it a sunflower, or could it be something else?

Even though the VMS 93r “sunflower” has a number of possible identifications (both New and Old World), Janick bases broad conclusions on this unproven ID as though it were fact:

“Simply put, there is no way a manuscript written on vellum that contains a sunflower and an armadillo could have been written before 1492,” —quoted on Purdue The Exponent news site, 10 Sep. 2018

There isn’t any proof of the identity of the “armadillo” either. It looks more like an Old World pangolin than a New World armadillo, but even this identification can be contested.

What I see in the papers and book by these authors is a collection of inadequately researched suppositions combined in a circular argument to support a New World theory. They pick out a few similarities and ignore the larger body of contrary evidence. They identify two completely different fish as the same fish. One of the plants they identified doesn’t even grow in MesoAmerica. They ignore numerous significant details like the cloudband under the “armadillo”. They ignore alternate IDs for the sunflower.

Unfortunately, the authors’ identification of Voynich-like glyphs suffers the same lack of critical evaluation as the plant and animal IDs, so let’s take a closer look at those.

The VMS-like Letters in the Codex Osuna

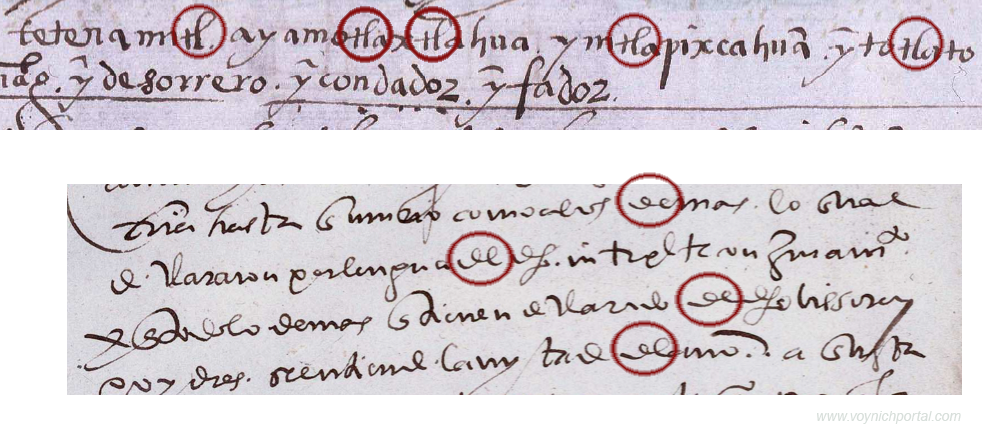

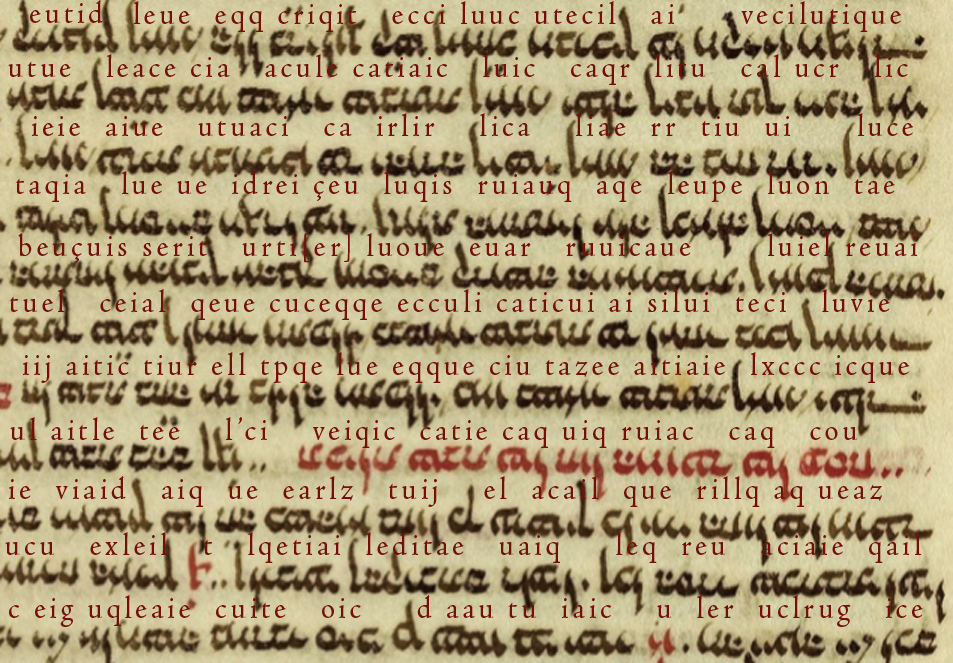

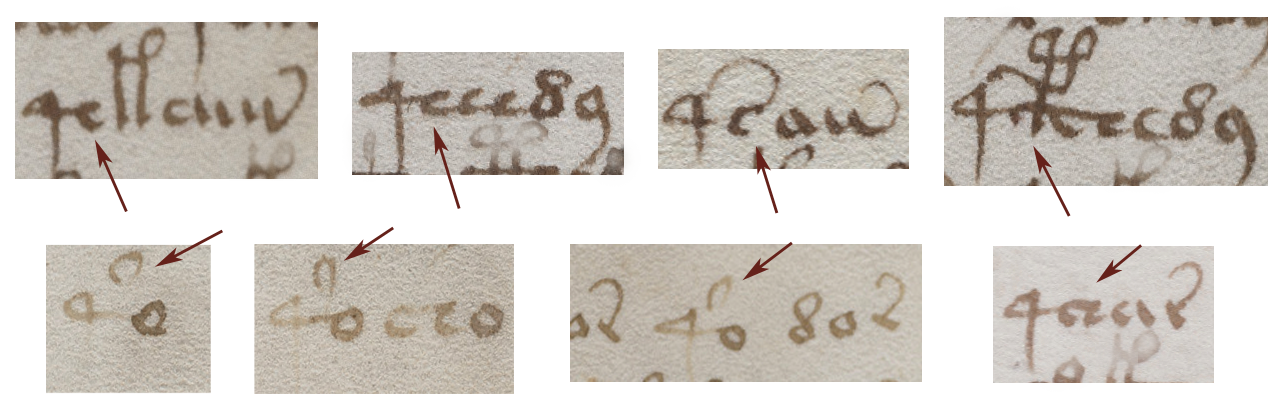

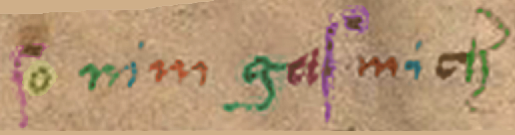

Here are examples of the Voynich-like glyphs cited by Janick and Tucker (and by Tucker and Talbert in a previous publication) in the Codex Osuna.

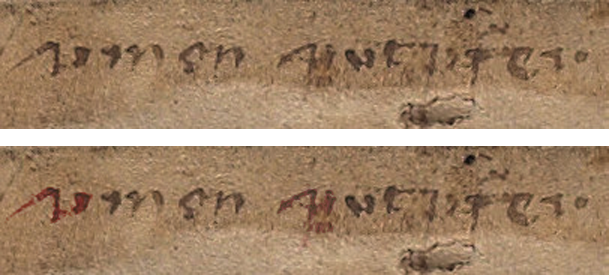

EVA-k is at the top, and EVA-t is at the bottom. Note that the handwriting is different:

Before you say, “Oh, those are similar”, make sure you read the rest of this blog. Bats and owls might look similar to a visitor from another planet, but one is a mammal, the other is a bird, and they are not closely related.

buy Lyrica mexico Visual Similarity is Not Enough (especially when they’re not actually that similar)

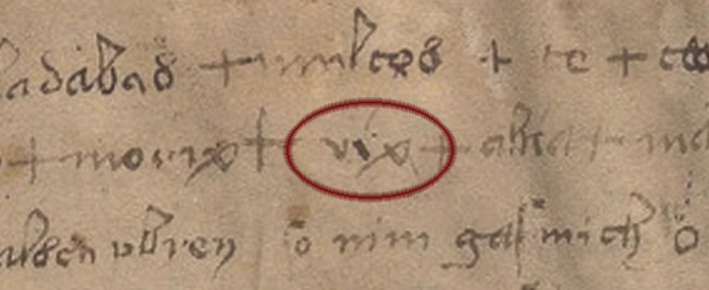

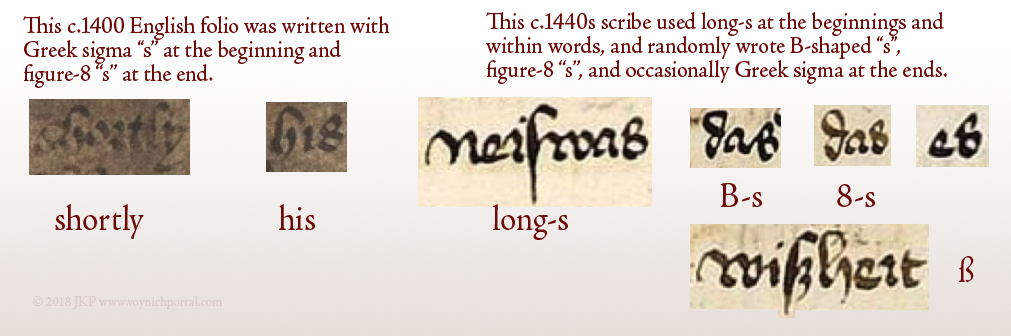

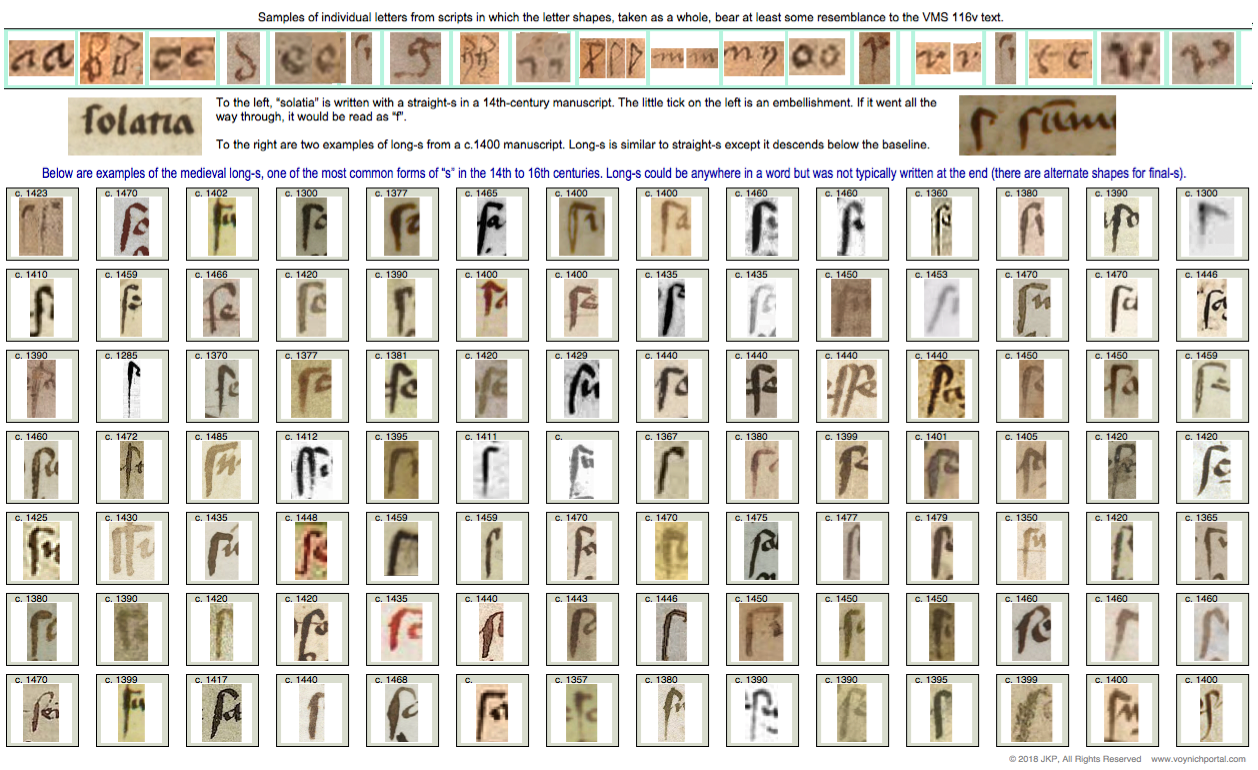

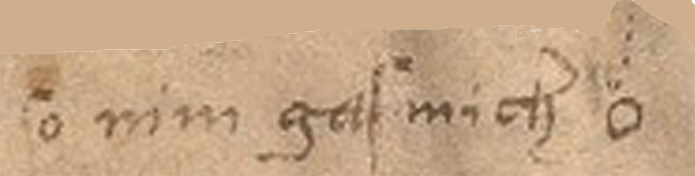

Something important Janick and Tucker did not mention is that the letters that appear to resemble EVA-k and EVA-t exist in two different scripts in two different languages. Failing to mention this distinction obscures the origin of these shapes, so I will fill in the missing pieces:

- The EVA-k shape is in the sections written in Nahuatl.

- The EVA-t shape is in the sections written in Spanish.

There are simple reasons for this, but they are important ones because there is no specific relationship between the Spanish and Nahuatl shapes. The similarities are coincidental, but some background might be necessary to make this clear…

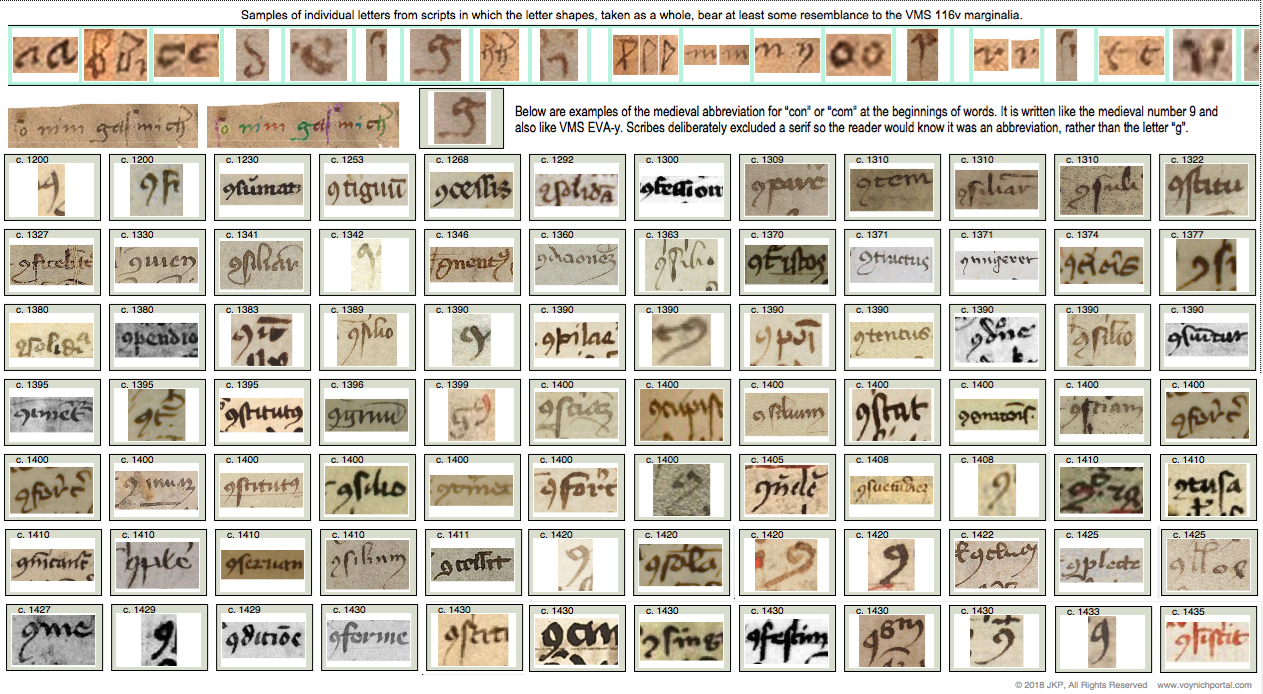

Nahuatl Version of EVA-k

If you’ve heard the Bushmen click language, you know it can be very difficult to express this with Latin letters.

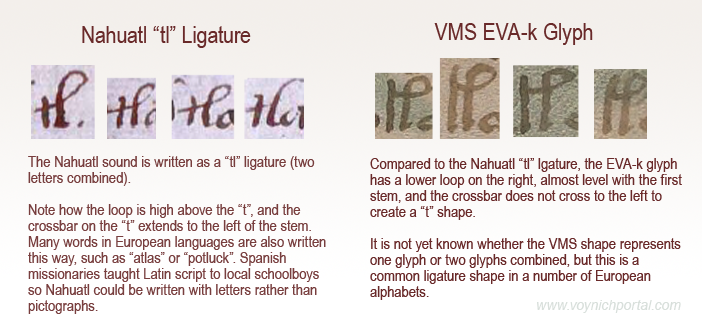

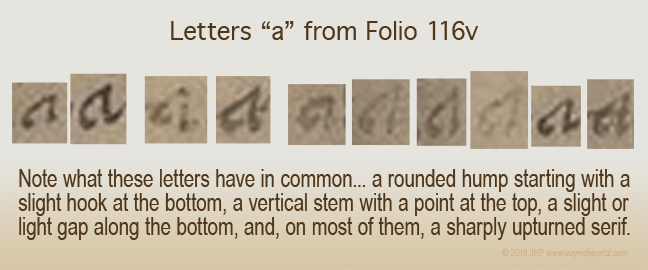

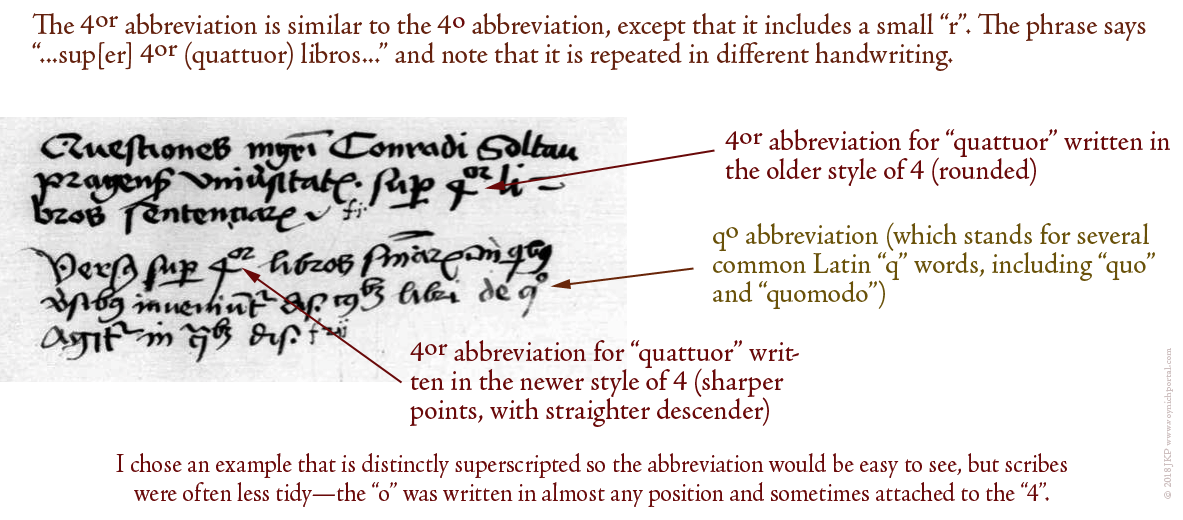

Similarly, there is a sound in Nahuatl that is hard to write. It’s made with the tongue against the back of the teeth, so the Spanish missionaries chose to represent the sound as the letters t + l and they wrote it as a ligature tl, with the crossbar of the “t” connecting to the loop of the “l”.

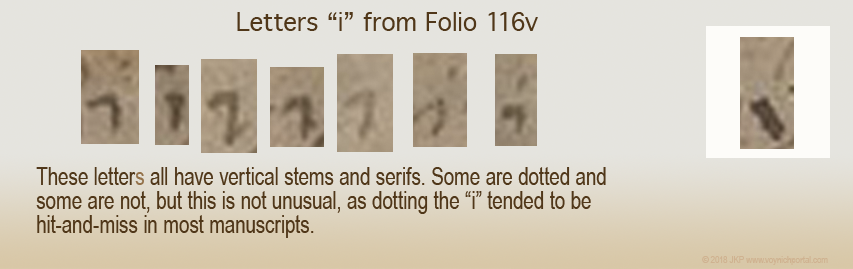

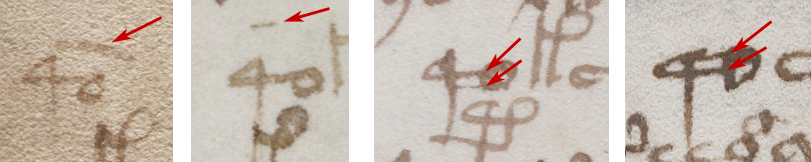

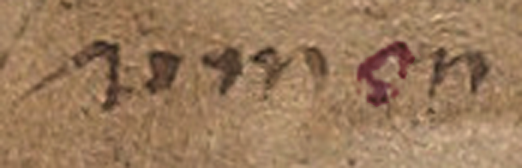

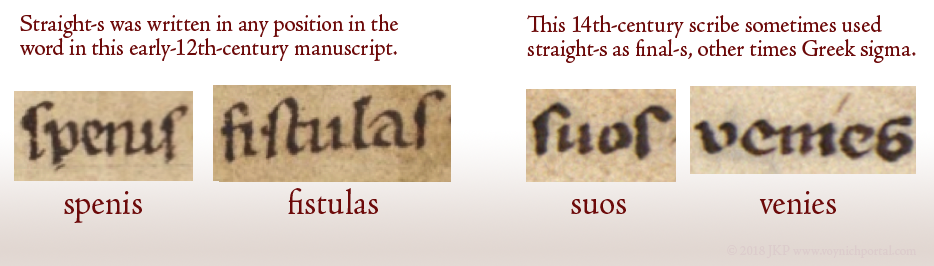

This ligature is not specific to Nahuatl or to the New World. It exists in Old World words like “atlas”, “battle”, “gatling”, etc. Note that the crossbar in the first letter “t” always extends some distance to the left of the stem, which is different from the way EVA-k is written:

It’s possible EVA-k is a ligature (two shapes combined) but if it is, then it follows age-old scribal conventions that are not specific to the New World (or to Nahuatl script). It doesn’t seem likely that VMS EVA-k was copied directly from Nahuatl if one goes by shape alone. It is more similar to some of the European ligatures and abbreviations such as “Il” (French) or “Item” (Italian, German, Latin) than the ligature on the left.

What About EVA-t?

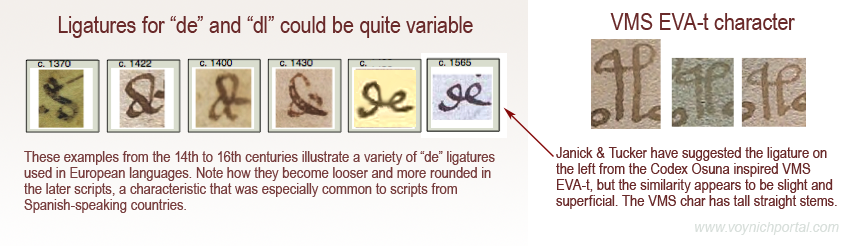

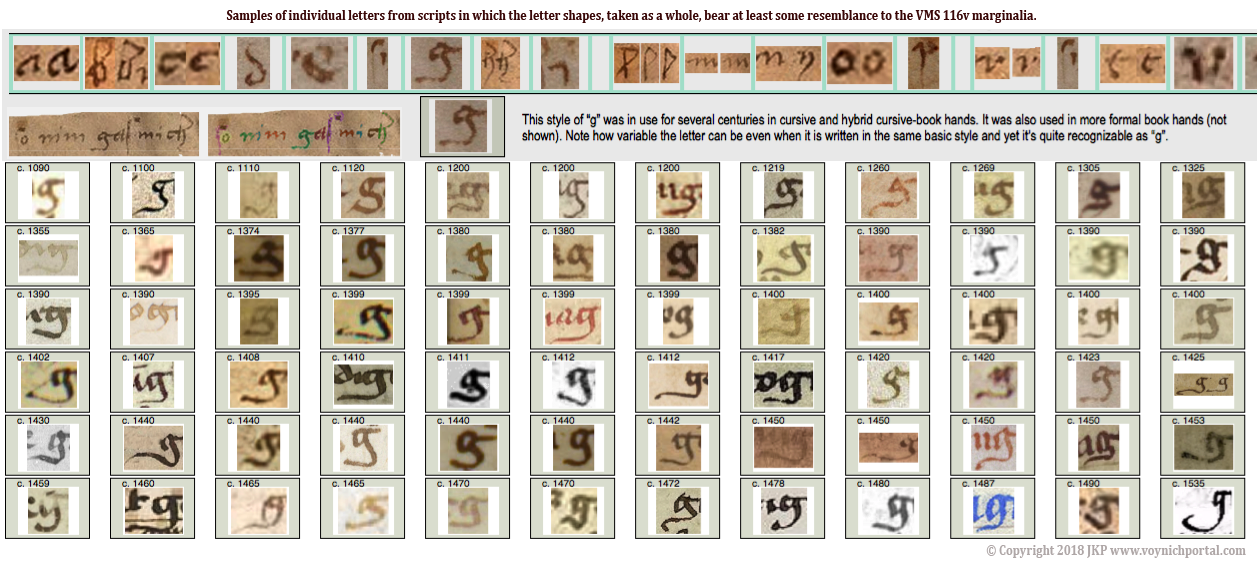

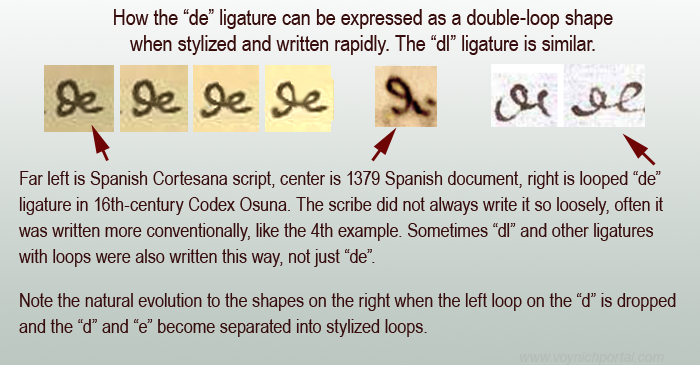

Another common ligature in Old World languages that used Latin characters was the d” + “e” and since the letter “d” was written a dozen different ways, the “de” ligature is quite variable. A similar ligature combines “d” and “l” as in words like “headless”. Sometimes they are hard to tell apart from each other and from ligatures like “il”, but the concept is the same—two letters are combined so they can be written faster or in less space.

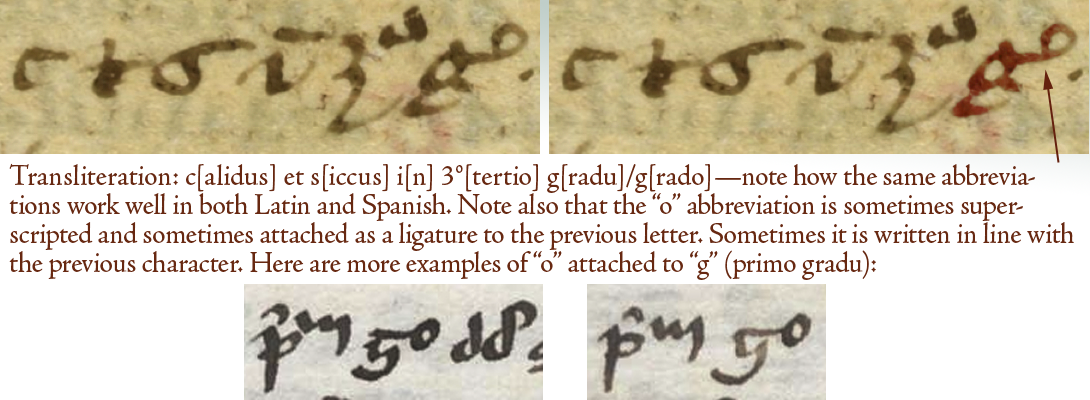

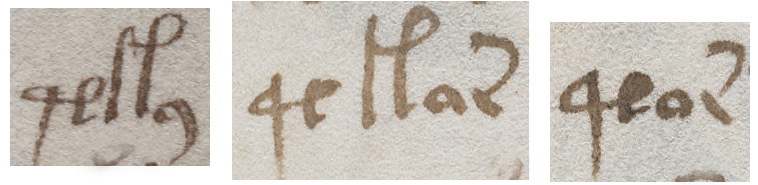

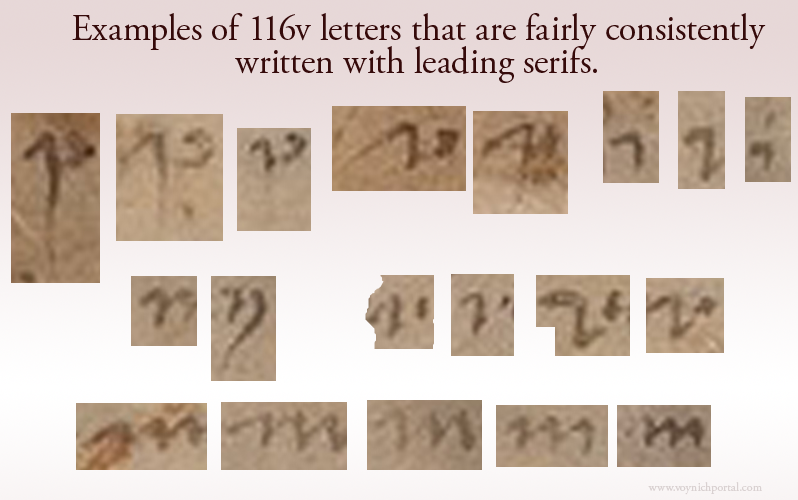

Here are examples of how “de” and related ligatures were sometimes written in Spanish scripts from the 14th to 16th centuries. The two on the right are from the Codex Osuna. The faster and loopier the writing, the more it resembles EVA-t (sort of):

The examples on the right illustrate how loose a ligature could be and how combinations like “de” or “dl” or “Il” or “Ie” need to be seen in context to be distinguished from one another, especially if it is an open-loop “d” followed by a very round “e” or “l”.

The examples on the right illustrate how loose a ligature could be and how combinations like “de” or “dl” or “Il” or “Ie” need to be seen in context to be distinguished from one another, especially if it is an open-loop “d” followed by a very round “e” or “l”.

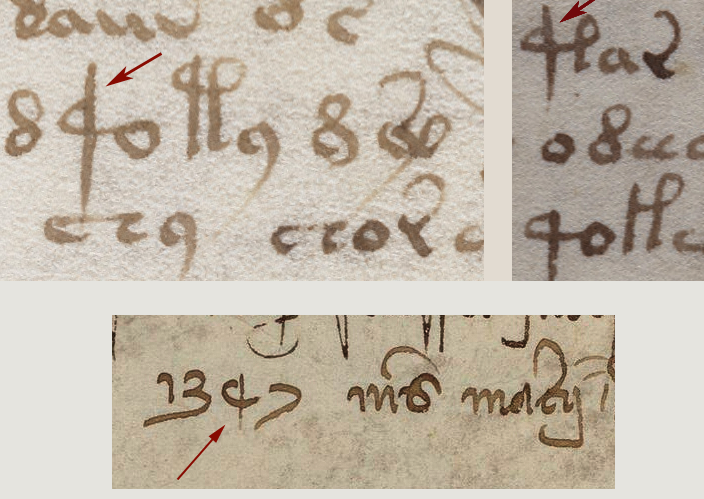

It has been suggested by Janick and Tucker that the glyphs above-right inspired EVA-t in the VMS, but this seems unlikely. EVA-t has long straight stems:

It’s possible the VMS char is a ligature, but even if it was inspired by “de” (I highly doubt that “de” was the inspiration but let’s pretend for a moment that it was), this ligature was common in many Old World languages.

The authors of Unraveling the Voynich Codex didn’t mention that the two shapes that resemble VMS glyphs are taken from two different sets of scripts (one in Nahuatl, the other in Spanish) and, more importantly, that these shapes were part of the normal scribal repertoire of Old World Europe and thus might have been seen by the creator of the Voynich Manuscript long before the conquest of MesoAmerica.

Summary

The authors didn’t provide any solid evidence that the inspiration for these shapes was specifically New World sources. In fact, the position of EVA-k and EVA-t within VMS tokens doesn’t match well to Nahuatl letter order, either, which further weakens the authors’ interpretation of the VMS script as a Nahuatl substitution code.

I’m not entirely opposed to New World interpretations. I think the VMS is probably Old World, but I will listen to New World arguments, as long as they are good ones. Unfortunately, many New World theories are marred by faulty logic and hasty conclusions.

J.K. Petersen

© 2018 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved