27 June 2019

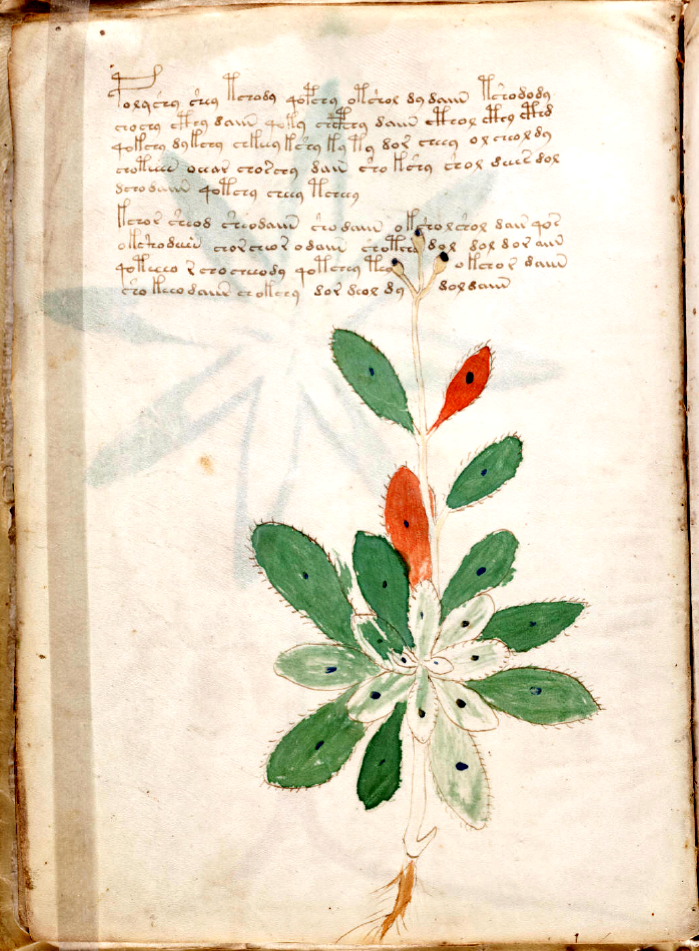

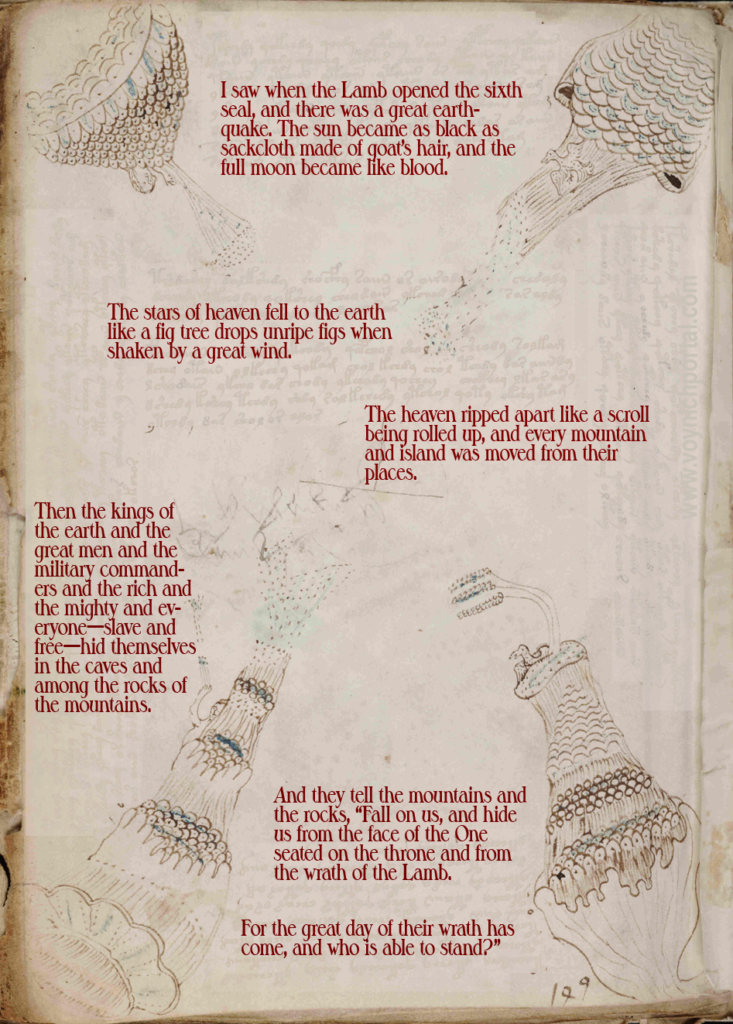

On folio 84r of the Voynich Manuscript, there is a drawing of textured niches, with a row of nymphs below its arches. Between groups of nymphs one might expect columns, but instead there are wavy lines painted blue, resembling a flow of liquid. The nymphs are thigh-deep in water that has been painted green. As with some of the other water-related drawings, the textures and “drips” give it a grotto-like feeling.

To the left is a pipe-shape with a large opening at the top and a smaller one at the bottom. A thinner rivulet connects the image to another pond pic at the bottom. Note that the water-like pools and rivulets on the left are blue.

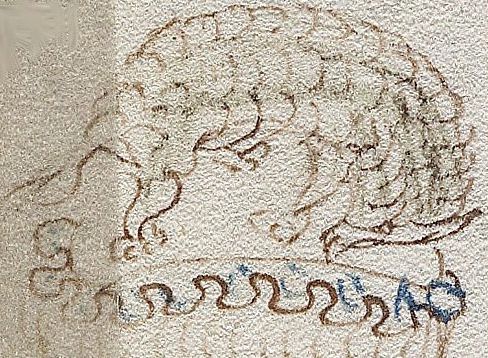

In the top-left is a scaly textured mass that reminds me of the shape in the corner of 86v (right). It holds a high position and appears to have something pouring out of it (air? water? spiritual emanations?).

Each archway is adorned with hanging-bead curtains, but since I don’t think the VMS is a drug-induced 1960s-era hallucination, perhaps the “curtain” shapes represent dripping water or an artistically shadowed backdrop.

Pinpointing the Poses

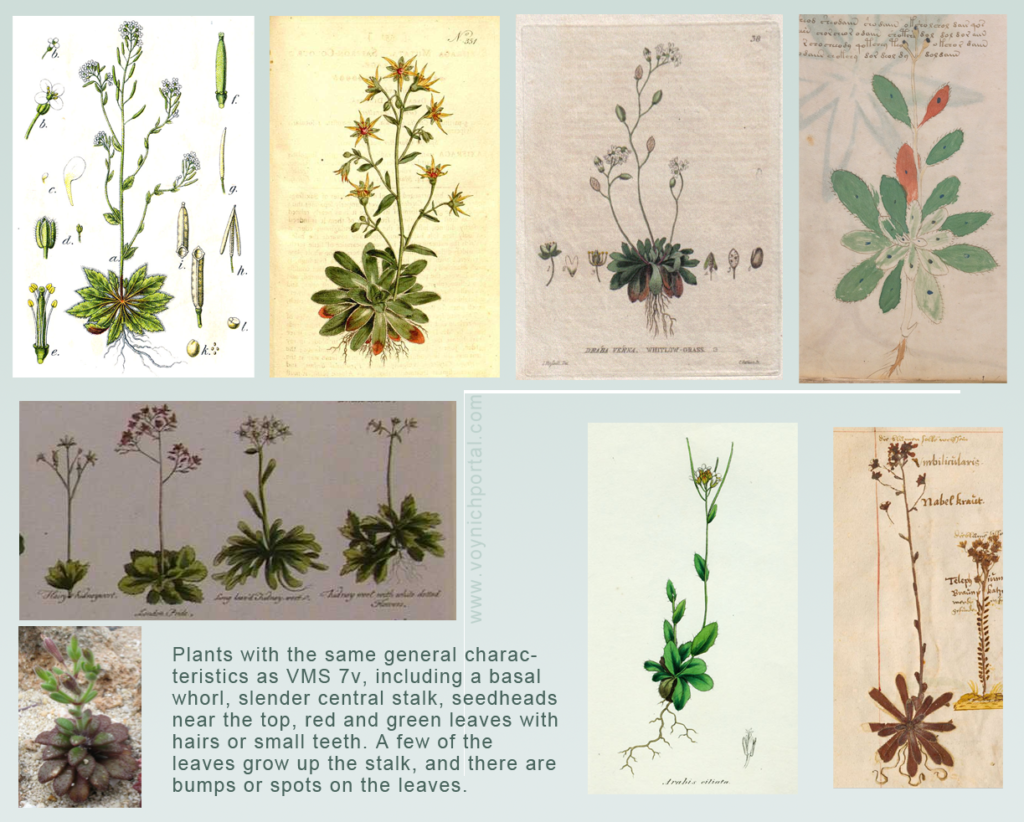

To me, the nymphs have always looked very posed, like actors demonstrating something, or as though they were frozen in time. When I first saw it, the middle illustration on 84r reminded me of frames from an animation, or a sequence of movements in which one nymph’s motion follows from that of the previous, as though each one were waiting her turn in line:

Part of the reason they look so posed is the formulaic way in which they are drawn, but these poses have always intrigued me because they seemed somehow familiar.

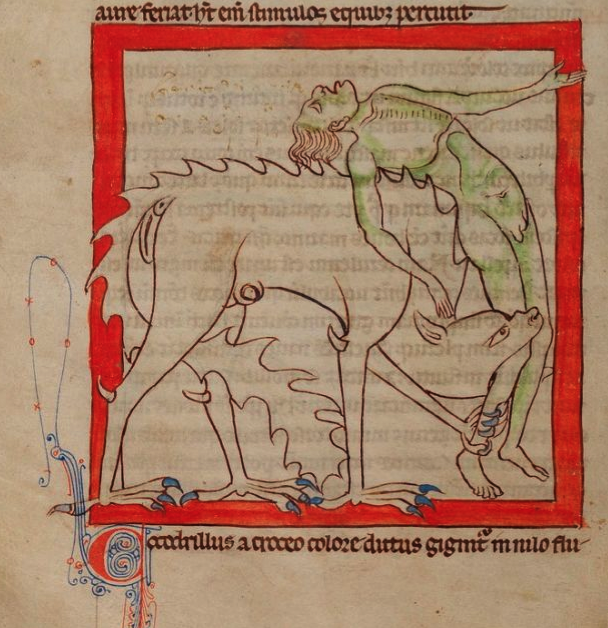

Here is a 13th century image of Tisbe and Piramus, the famous lovers who whispered sweet nothings through a crack in the wall—the forbidden love that inspired Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream:

Even though they are quite posed, I don’t get the feeling the nymphly pool party was inspired by this story, so I looked for other examples.

There is too much on this folio to cover in one blog, so I’ll constrain my comments to the nymphs at the top, under the arched textures.

Posing in Pairs

Let’s look at how the nymphs are arranged…

At the top of 84r are four tightly coupled pairs and two nymphs who look like they might be holding hands from farther away. Flanking them are two additional nymphs that seem slightly set apart from the others, as though engaged in a different role.

Some of the nymphs are partly obscured by their pair-mates, and the paired nymphs are back-to-back as though they just passed each other.

I can’t quite tell if some of the couples have their elbows entwined, because the drawing isn’t very good, but there is almost a suggestion of this in at least one of the pairs. Their gestures are distinctive because they are expansive and seem to point beyond the confines of the niche:

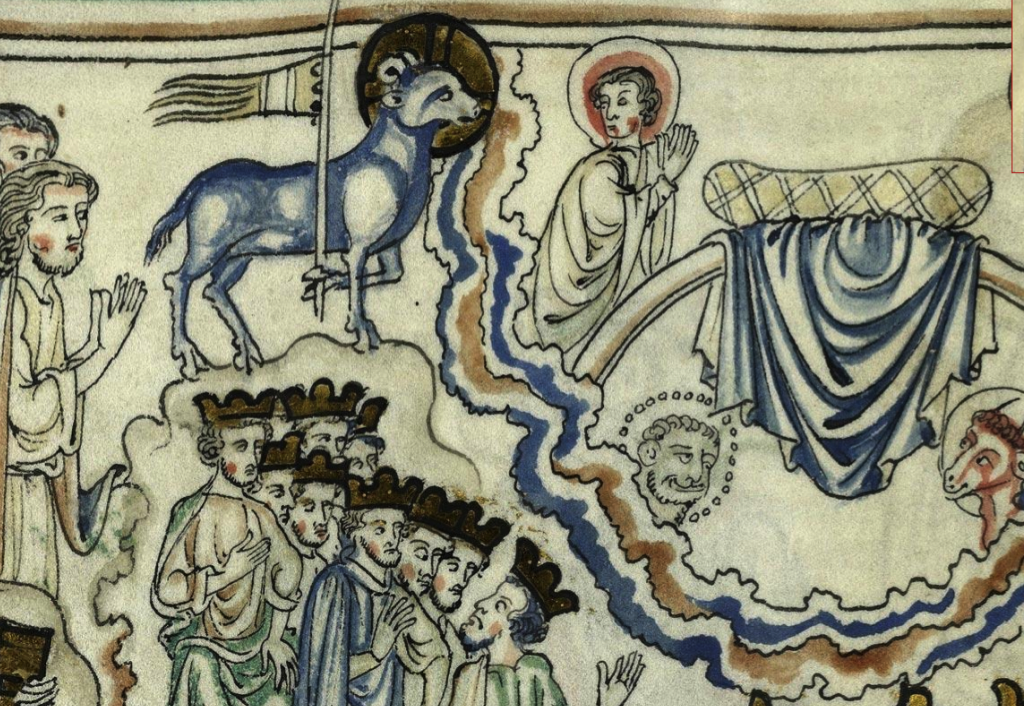

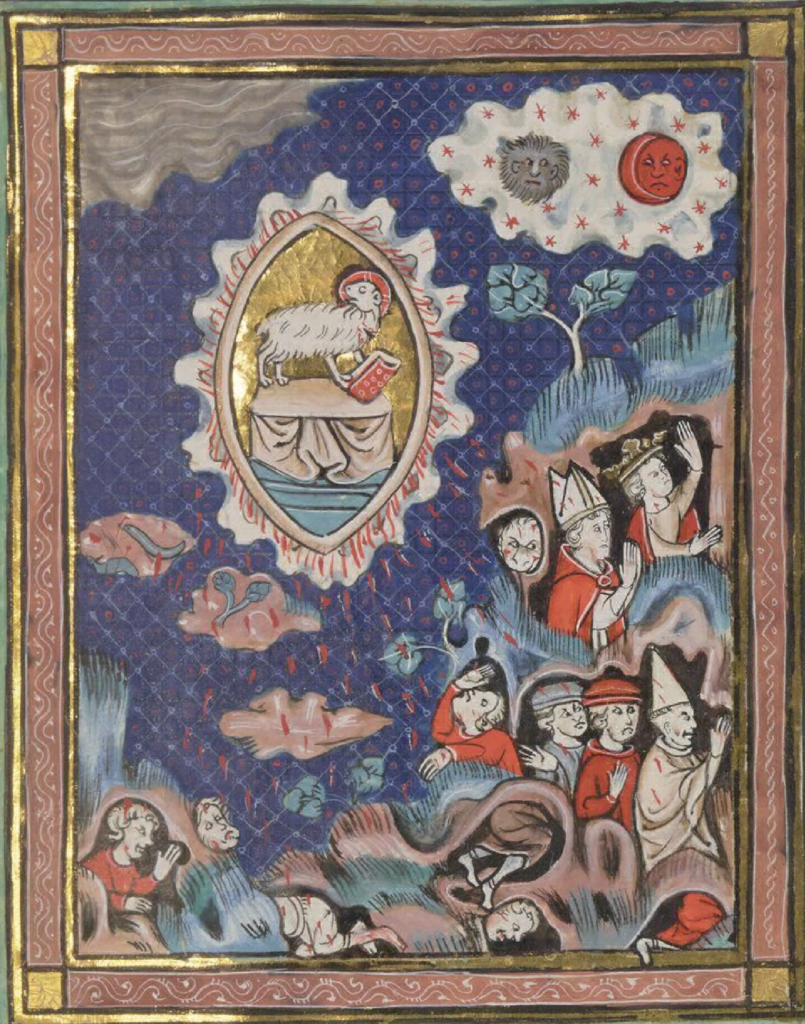

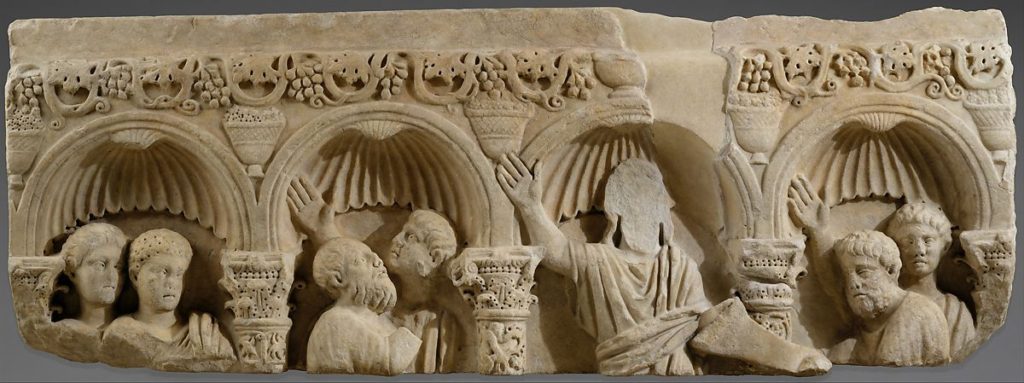

It was the pairing and extended hands that drew my attention to a Byzantine relief sculpture with archways and paired figures:

Note the shell-like “curtains” at the back of the niche, with their downward-pointing lines and lightly scalloped edges, and how the gestures of some of the figures seem to point at something beyond the archways:

The nymph on the left is posed similarly to the figure on the sarcophagus, but the one on the right seems to be in some kind of LSD-induced reverie. She looks like she is about to serenely leap off a cliff. Or perhaps, in a moment of zen, she knocked her opponent to the ground with the heel of her board-breaking hand. Well, maybe not. There might be other explanations…

For some interesting ideas on VMS poses, refer to K. Gheuen’s blog.

Is there some overall pattern to the nymphs’ gestures that might explain the poses? Are these poses typical or uncommon?

Pairs and Poses on Sarcophagi

This row of figures, similar to the fragment in The Met, is on a sarcophagus from the Alyscamps cemetery, in Arles, Provençe:

Christ stands in the center, flanked by figures in twos and threes within scalloped archways, but the gestures and poses in this relief are not as close to the VMS as the relief in the Met.

The arrangement of the figures in pairs, with one obscured by the other, and the slightly more expansive gestures, is similar to another 4th-century sarcophagus in the Gregoriano Profano Museum, but it lacks the shell-like embellishments and archways:

The theme of many of these sarcophagi is traditio legis and Christ is often shown at the center of apostles and evangelists handing a scroll to St. Peter. There are twelve nymphs, a number associated with apostles, but there is no suggestion of a Christ-like figure or evangelists in the VMS pool party.

This example of traditio legis, from Chartres cathedral, differs from the VMS and The Met sarcophagus in a number of ways, including the elevated position of Christ and symbols for the four evangelists. Below them, each apostle has his own archway, in groups of one or three between the pillars. The poses are constrained, and the gestures do not point to a distance beyond:

The tympanum of the south portal of the Abbey Church of St. Pierre, Moissac (12th century) is similar in arrangement to the one at Chartres, except that the apostles are sitting, and a wavy cloudband (instead of arches) separates the Christ imagery from the apostles:

The figures of a sarcophagus from the Basilica of S. Ambrogio, Milan, are also quite constrained. They are arranged in a tidy row, slightly overlapping, and there are no fully-extended hand gestures. There are archways, but they are narrow, and placed behind (rather than around) the figures:

There is a large, very ornate relief in the tympanum of the abbey S. Foy à Conqes in France. The lower left corner feature twelve figures in pairs within archways, surrounding a Christ figure with his arms around two smaller figures:

But the figures all look very respectable and constrained, no expansive gestures.

What we find is that pairs of figures within archways, combined with expressive highly extended gestures, are not common. It also seems to be easier to find VMS-like paired-poses in relief sculptures than in manuscripts, a situation that is reminiscent of some of the earliest VMS zodiac themes, which appeared on churches before they became common in manuscripts.

Another Viewpoint

Moving away from the arches for a moment, could there be another reason the nymphs are extending their arms and shown in pairs? Is it possible they are dancing?

The two VMS nymphs to the right look like they might be holding hands through the stream of liquid, and the two on the left look like they might be about to touch hands, so there is a hint of interaction between them. In fact, pairing may exist in two different senses. There are pairs in which the nymphs are very close together, but back-to-back, and there might also be pairs where the nymphs are farther apart but making eye contact:

Are these poses similar to historical images of dance?

In this c. 480 BCE cippus (tomb-marker), a piper stands in the middle as two toga-clad figures dance with gestures that are reminiscent of Egyptian styles, and similar to today’s Middle Eastern and Eastern dances (note the angles of the elbows and wrists). The style of pose is even more apparent on the accompanying face (right) with three dancers:

This style of cippus and dancing pose was commonly depicted on funerary art in central Italy around the 5th century BCE, when Etruscans flourished in this area.

It has been asserted that the Etruscans came from a different language-family than Indo-European and that their DNA history is somewhat diverse (with a segment originating in Turkey). It is, in some cases, unique (neither European nor Middle Eastern). It has also been suggested that the Etruscans originated from the Sea Peoples, some of which are said to have migrated to the Middle East. Whatever their origin, these poses are more similar to Middle Eastern than to early modern European dance styles, perhaps through the Turkish connection.

If the VMS nymphs are dancing, the cippus style is not the style we see in the drawings.

And where are the women?

Woman in Motion

By now it should be apparent that most of the previous examples of figures in archways are male

Are there women in archways posed like the VMS nymphs? Do they compare to the VMS in terms of organization and gestures? Are the nymphs symbolic of mythical figures, people in general, or are they specifically meant to be female?

Here is an early Roman relief with three nymphs dancing:

The background is plain, no archways or shells. The head poses are provocative, but otherwise these nymphs look very chaste, dressed from head to ankle, with their hands barely showing, and the hands are simply clutching the drapes of the nearby nymph, not calling attention to themselves.

Women within Archways

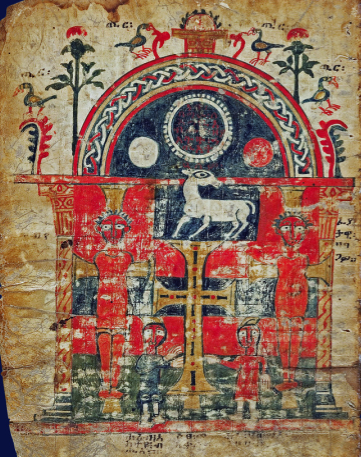

This old Pagan relief found in Carrawbrough features three water nymphs each with her own containers—one held high, the other illustrating the flow of water, each within her own archway:

This imagery probably descended from Pagan representations of the three water-nymphs (a trio of nymphs was a very common theme in Roman art) flanked by the god Zeus and Pan, but this older example does not include archways and the figures look at the viewer rather than interacting among themselves:

There is a relief of three dancing nymphs from Saladinovo (c. 2nd century BCE) in the Archaeological Museum of Sofia where the nymphs are more animated and the scarf-like fabric that flows around them almost has the effect of archways (the image is copyrighted by the Lessing archive, but you can view it here).

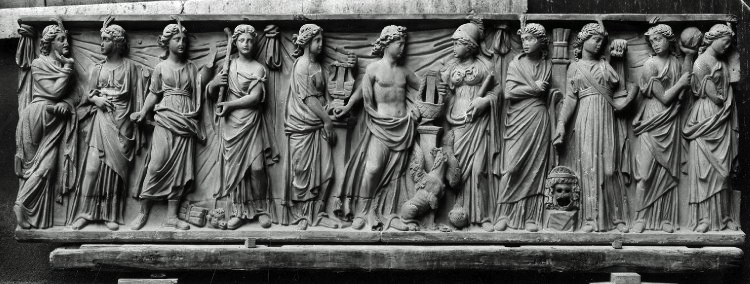

Here is a scene with Apollo, Athena, and the nine Muses, with two pairs on either side of the central figures, but the gestures are not expansive and the figures are not within archways:

Another Christian-themed example of figures within arches is the story of Adam and Eve and their expulsion from the garden, shown here in a Modena relief by Wiligelmo:

The Modena relief is interesting because it doesn’t just show a static event, it is, in a sense, a cartoon-strip style, with each section representing a different event in time. In other words, this storytelling format existed not only in medieval manuscripts, but in relief carvings as well, lending strength to the possibility that the multitude of figures in the VMS might not always be different people, perhaps some of them are the same figure in different points of time.

Myths and Muses

Something a little closer to the VMS pool party is an Italian sarcophagus with nine muses. In the center is a single figure separated from the paired nymphs on either side by two theatrical masks. It is similar in form to the traditio legis except it has a Pagan rather than a Christian theme.

So one can find women in pairs in archways, but the figures don’t overlap as much as the VMS characters and the gestures are less expansive:

As we go farther east, we see increasing differences in clothing and the ethnic features of the figures, but there are some similar themes. Here is one with figures in groups of two to four within niches, but there are no arches or out-reaching hands

It seems that groups of woman in motion are largely dance-themed.

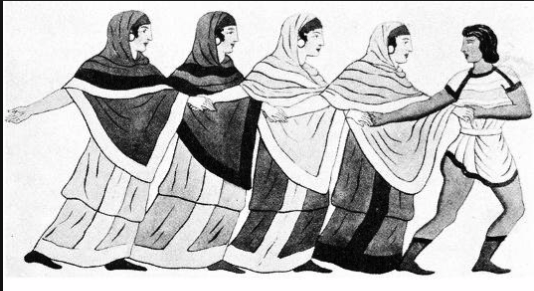

There is a pre-Roman Peucetian fresco in Ruvo di Puglia, Italy (c. 5th century BCE) that features a row of fully robed women dancing, each one holding hands with the second person behind:

There are no arches, but the gestures are a little more expansive and interactive than most of the relief sculptures.

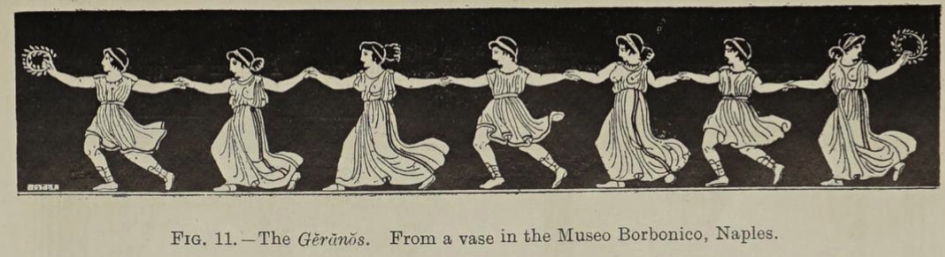

In the next example, male and female dancers alternate and the action of their feet is more lively (this particular theme of “line dancing”, with hands touching, is quite common in ancient Greek art):

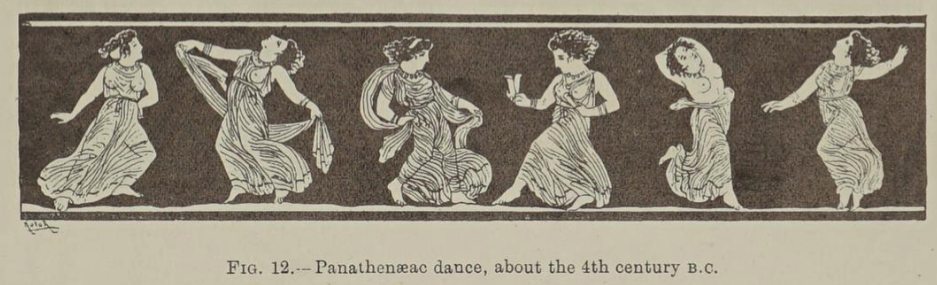

And this example from the 4th century BCE is quite unrestrained, one of the few with truly expansive gestures (perhaps a little too much Retsina), although there’s no actual physical contact between the figures:

There is a legend about the nine muses dancing with Apollo, and here we see them in a painting by Baldassare Peruzzi (c. 1510) based on traditional imagery:

In some of the earlier depictions, Apollo was to one side of the muses, playing a lyre.

Stylistically, these western dances are quite different from eastern depictions, some of which can be seen here.

Illuminations

The above images are mostly on frescoes and relief sculptures. What about imagery in manuscripts? As I’ve mentioned before, when writing about the zodiacs, it was easier for most people to view architectural art than to have access to a manuscript. A manuscript cost about a year’s wages, sometimes much more. There were a few chained libraries, but most of the manuscripts were in the private collections of kings and nobles. Embellishments on public buildings and open-air sarcophagi were free.

Nevertheless, I tried to find examples that might bear some relationship to the VMS in manuscript art.

In the Florentine Homer (1466), Homer is surrounded by nine muses (one behind his shoulder) and four wise men. There are roundels rather than arches, and each nymph is in a different pose. In total, there are 14 figures, so it doesn’t quite match up with numbers in the VMS:

But muses would only account for nine dancers and the VMS has 12. If there is any connection between the VMS and classical literature, that discrepancy might be resolved by the three graces, who were sometimes shown together with the nine muses:

And then, of course, to come back to a more literal interpretation of the VMS drawings, there are images of bathers in outdoor environments.

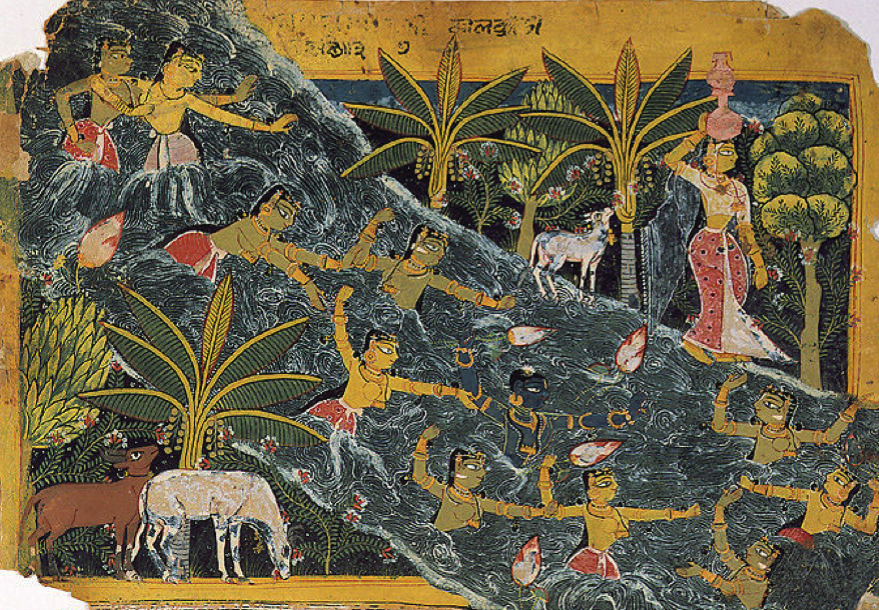

In the Bhagavatapurana, in a tropical locale with fast moving water, the gestures of bathers are quite expansive and almost like dancing. However, this version postdates the VMS by about a century-and-a-half. In general, expansive gestures are easier to find in later manuscripts than in earlier ones:

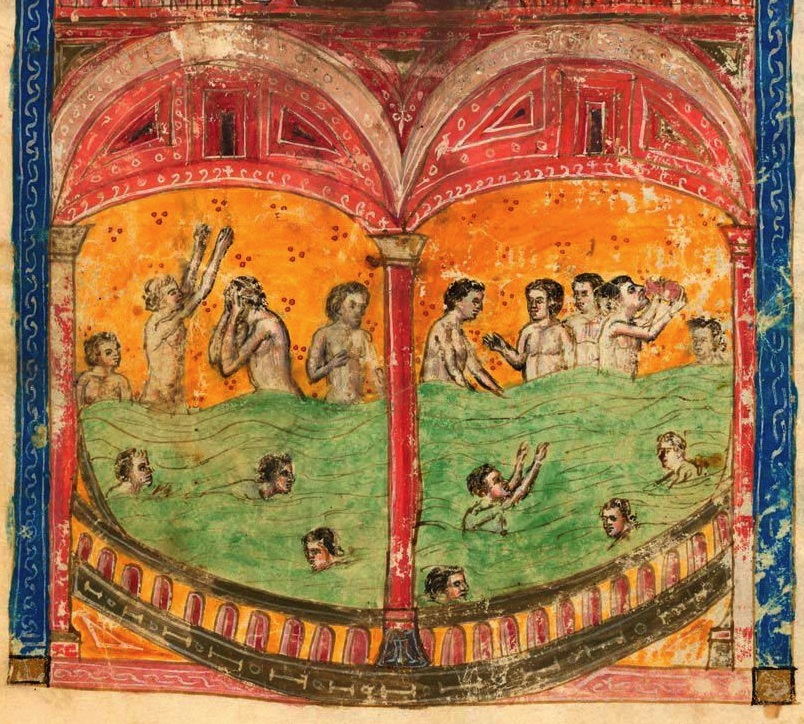

In De Balneis Puteolanis from the 14th century, bathers are shown within archways, in groups of two or three. This spa in the Naples region was still in operation at the time the VMS was created (it was destroyed by a volcanic eruption in 1538):

This c. 1400 version of De Balneis from Italy not only has bathers within arches, but the gestures are fairly lively:

The figures don’t quite have the “posed” look of the VMS nymphs, however. The Pozzuoli image looks more like recorded history than a morality play.

It is interesting to note, however, that the image expresses two sets of activities. At the top are people rinsing their faces and talking, on the bottom are people more fully immersed, some of whom might be swimming.

The VMS also has levels. In the top image, the nymphs seem to be dancing. In the second one, below it, they look more like they are washing. In the third, one is bent over with her hand on her buttocks (washing her butt?) and most of the others have their hands by their butts, as well. A nymph on the left holds out an object… is it a sponge?

Here is a 17th-century depiction of nymphs bathing in arched grottoes, with the natural structures enhanced with added stonework. Could the VMS setting be based on something like this?

Summary

I can’t tell if the top pool of the 84r is meant to be literal or allegorical, but I think there’s something extra going on in the arrangement of the nymphs. If it’s a literal representation, maybe the pool party included dancing. Dancing was a very popular form of entertainment before television was invented, and every well-born person was expected to know basic steps.

Or maybe the nymphly poses are telling some kind of a story, as in the panels of Piramus and Tisbe. Either way, pictures of dancers with expressive gestures in the style of the VMS, set within archways, were not common in the early 15th century, so it might be significant that the closest parallel I have found so far for the gestures, was on a Byzantine sarcophagus that traveled from Rome, possibly through Paris, and eventually ended up in the United States.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2019 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved