25 March 2020

In medieval times, people walked. Many cities were completely walled and you entered by the portal gate. Some cities had only one entrance. Some had three or four. If there was only one, it was important to know where it was or you could approach from the wrong side and spend hours or days backtracking along treachorous mountainous paths or deep forest.

To make it easier to recognize the gate from a distance, certain “signal” styles were adapted by builders and architects, many of which were specific to their region. It was common to build a tower, or a pair of towers, over the main portal. The extra height let the watchmen see who was coming, and visitors knew where to approach.

Portal-Tower Architecture

Most towers were built with brick and mud or stone according to local engineering and cultural traditions. Some had flat platforms, others had roofs.

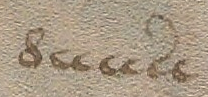

The Canaanite Gate in Tel Dan is several thousand years old and currently under restoration (the doorway has not been fully excavated). It features a heavy wall and a single portal in the central recessed portion of a thick wall. The portal is within a broad arch that predates Roman arches by about 1,500 years. There may have been a higher central tower above the doorway at the time of original construction:

This basic format, a strong wall, a central portal, and a raised platform or tower over the doorway was common to many countries.

There are a number of ancient gates in Bosra, in southwest Syria. They typically have arched doorways, but high towers above the gate are not usual.

The Gates of Istanbul are massive, with mostly-square towers, and very old. Some have been bricked up or restored over the years. This is the Belgrade Gate which still includes parts of the original wall:

Portions of the wall ran along the water and a chain was stretched over the canal to prevent undesired entry by boats.

Here are two examples of medieval tower portals from Cairo, Egypt. The well-fortified north-facing portal (left) has a platform and crenellations. The south portal (right) has elaborately carved minaret towers and stone roofs with sculptural finials:

The bastion style on the left was a common style. It was designed for visibility and also for protection. It enabled guards to drop arrows, rocks, and burning oil onto anyone trying to storm the gate. This form of tower is often depicted in manuscript illuminations.

The Porta Soprana of Genoa, built in the 11th 12th century, is similar to the north-facing portal in Cairo, although not quite as massive. Between the two round towers, and on the top, are Ghibelline merlons, but it’s difficult to determine exactly when they were added. It is possible, in this case, that they are original, since this is one of the pockets where there were Ghibelline supporters, but since the portals were intended, in part, to assert the independence of Genoa, it’s questionable whether they would include a symbol specifically supporting the Holy Roman Empire:

The little town of Münchenstein, on the northern Swiss border, had quite a simple portal with a square tower and crenellations:

The Augustus Arch, portal to Rimini, is very ancient and classical in design with an unusually large opening that probably never had a gate. The Ghibelline merlons were added in the 11th 10th century when the Ghibelline family took control of the city:

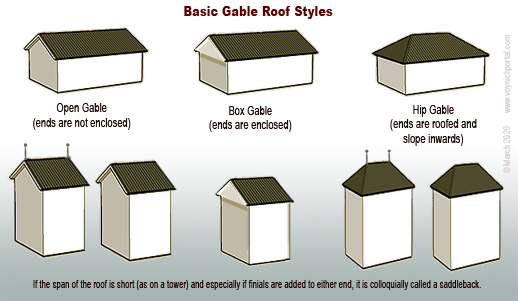

Gable Roofs

Sometimes towers had roofs similar to those on houses. A common style was the gable roof, seen in areas where ceramic or wooden roofs were added:

The span of a gable can vary. If it is a short-spanned gable with finials or raised peaks at either end, it is sometimes called a “saddleback” because of the resemblance to saddles with raised pommels and cantles (right).

Saddlebacks were common in Bohemia/Bavaria, Alsace, and parts of eastern France in the Middle Ages.

Historic Portals

The Butcher’s Tower (below) is a hip-style gable with inward-sloping sides and roofing materials on all four sides.

This picturesque watchtower was built in the 14th century, and stands above an entrance gate in a long wall.

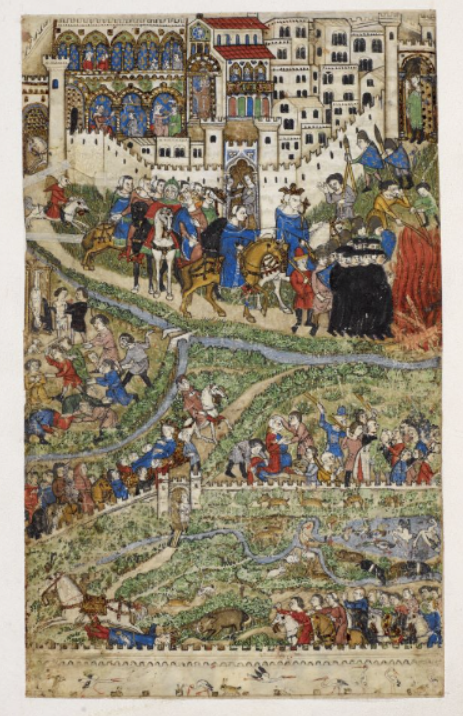

A similar style of portal can be seen in the Berner Chronik (Burgerbibliothek Mss.h.h.I.1), created between 1478 and 1483. It has a hip-gable saddleback roof with finials:

The main difference between this and the Butcher’s Tower is that the Berner Chronik portal has a crenellated level where the stone ends and the roof begins. In some cases, towers started out unroofed and roofs were added later. In other cases, there is a crenellated balcony at the apex of the stone that was part of the design.

In this illustration, there are two entrance portals built along the water for accessibility by boat and for extra security. Both portal towers have saddleback roofs with globe finials, but the tower on the left has a viewing window and the one on the right has a covered walkway leading to the opening:

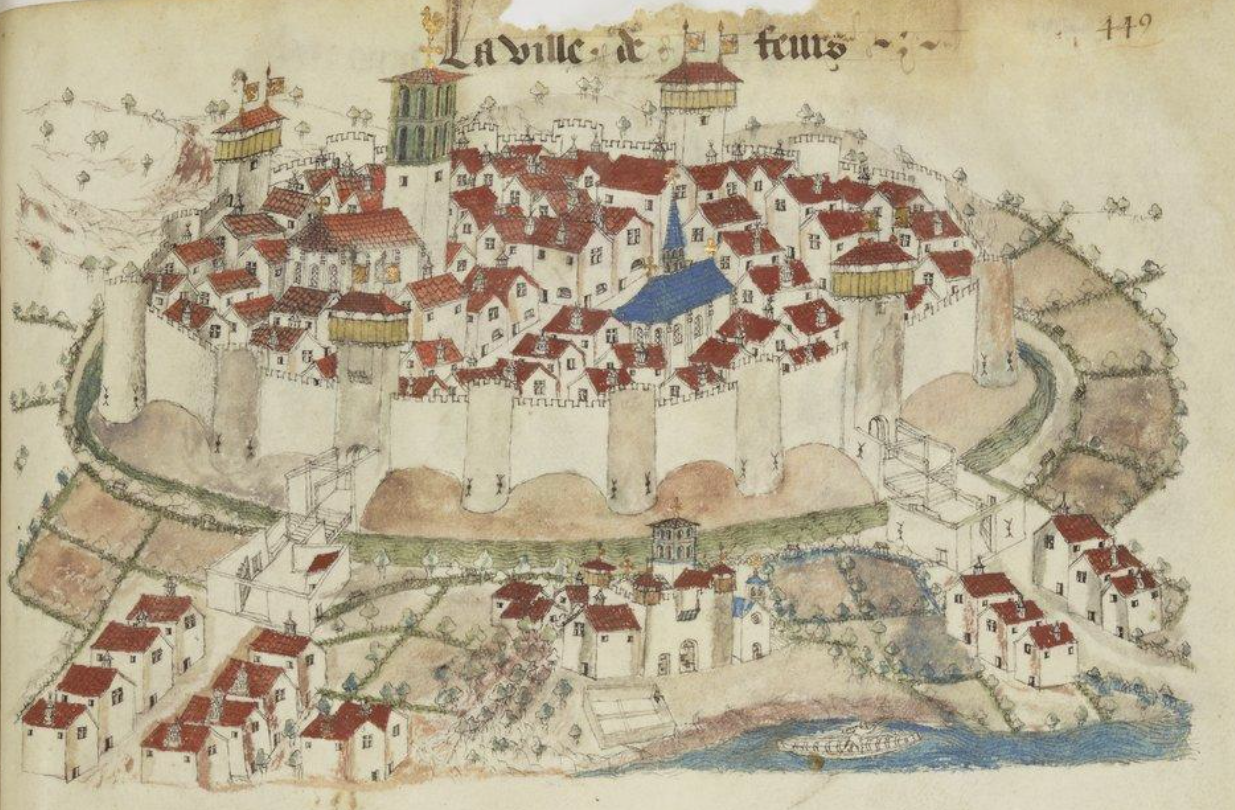

Postscript 29 March 2020: I forgot to add the following drawing when I posted this blog, but it’s worth including because it’s part of an extensive collection of town maps from the mid-15th century. The drawings of Guillaume Revel are generally more accurate than castle drawings in storytelling manuscripts because part of his purpose was to document ducal holdings.

Revel drew the town of Feurs around 1450. There are four saddleback portals, each with flag finials and, unlike most castle drawings, he included details of the archways and balcony just below the rooftops, a style that was fairly common in this area but not always elsewhere. Between the portals are semicircular wall towers with simple battlements:

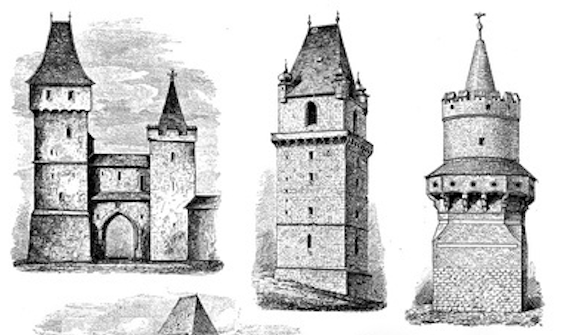

The following examples of German towers include 1) double towers, one with a hip-gable saddleback on the left and a cone-shaped tower on the right, 2) a single tower with a saddleback roof and globe finials, and 3) a finial-topped cone tower surrounded by a balcony with battlements:

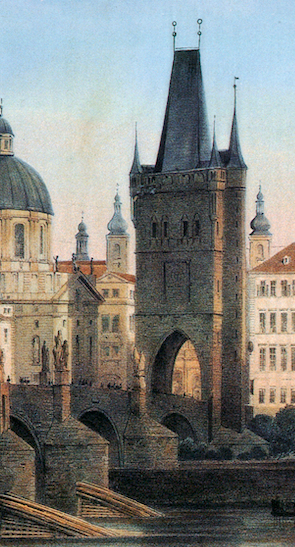

The Prague “Powder Tower” is situated on one of the main city portals on the Charles Bridge. During the reign of Emperor Rudolph II, it housed some of the alchemists

It has a hip gable with globe finials and turrets in the corners, similar to the tower in the center diagram above, but the Powder Tower was not built until 1475 and I couldn’t find any clear pictures of the original tower it replaced.

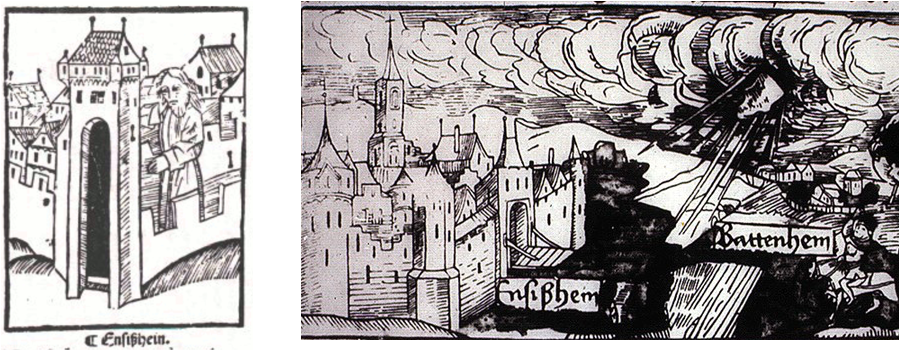

Towers similar to the Powder Tower served as portals to the cities of Batteheim and Ensißhein.

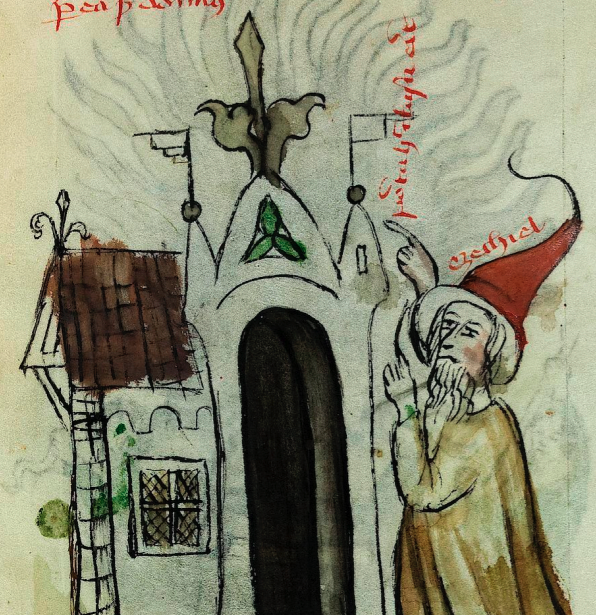

Sometimes local architecture was used to illustrate events in far-off places. For example, Vatican Pal. Lat. 871, includes a biblical story of Ezechiel that obviously didn’t take place in central Europe, and yet the illustrator drew local architecture, including a pair of flag finials facing outward:

On a side note… outside Ensißhein a meteorite boomed out of the sky and landed in a field November 1492. A number of woodcuts and drawings commemorating the event show a saddleback portal gate (a 15th-century drawing of Belgrade includes similar-looking portals):

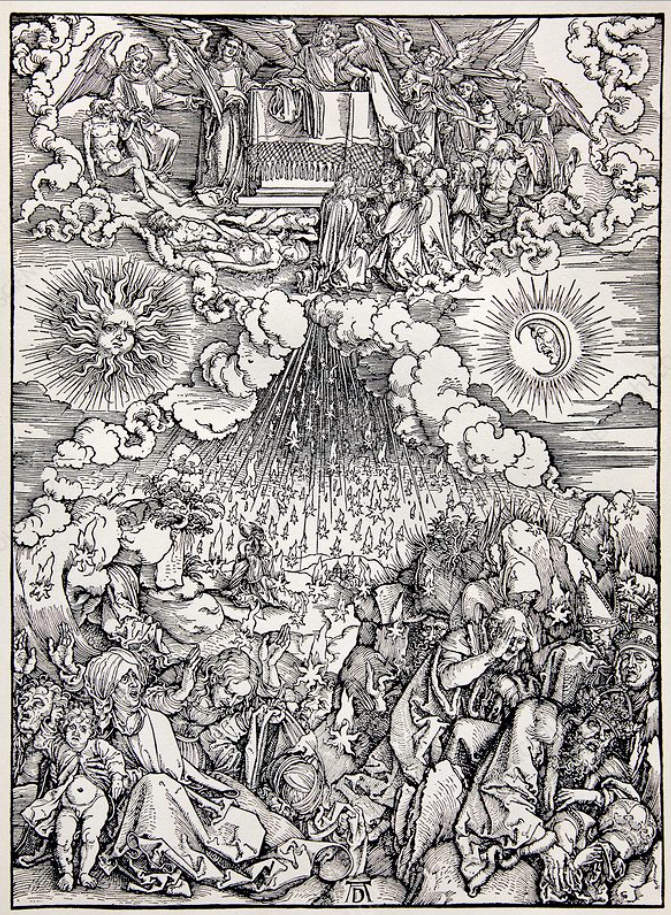

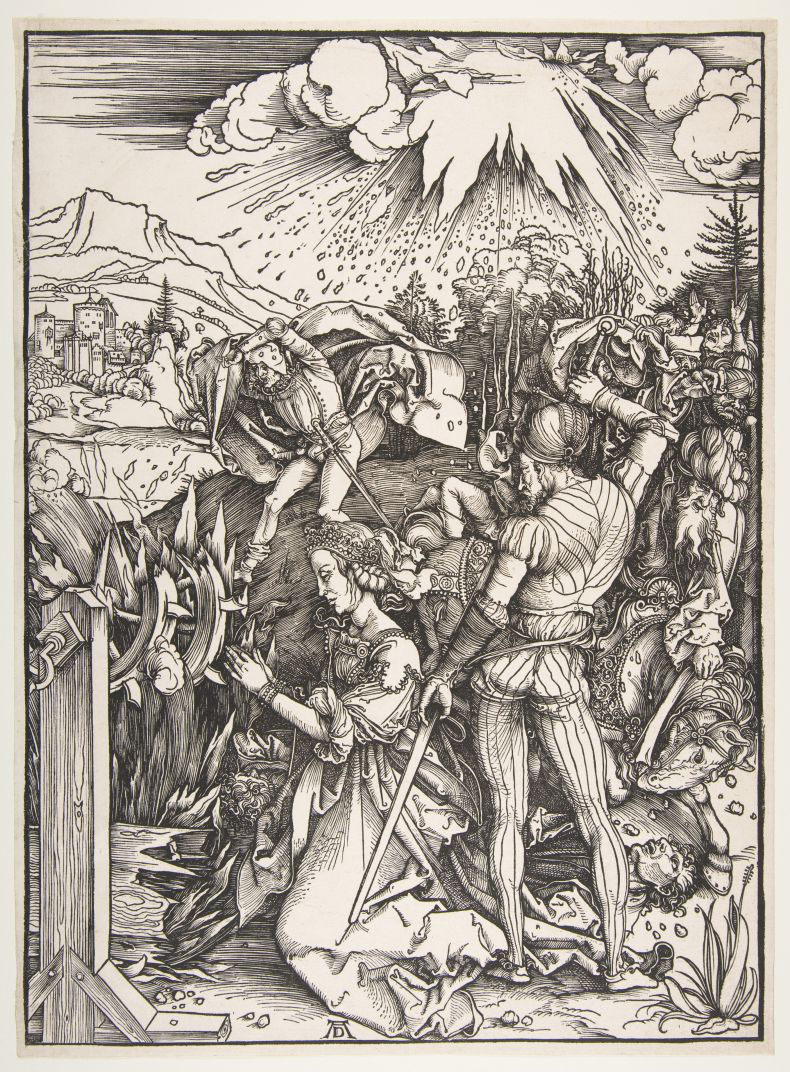

Albrecht Dürer created elaborate allegorical engravings of the meteorite event replete with sun, moon, stars, cloudbands, angels, and people cowering in fear. Here are two examples:

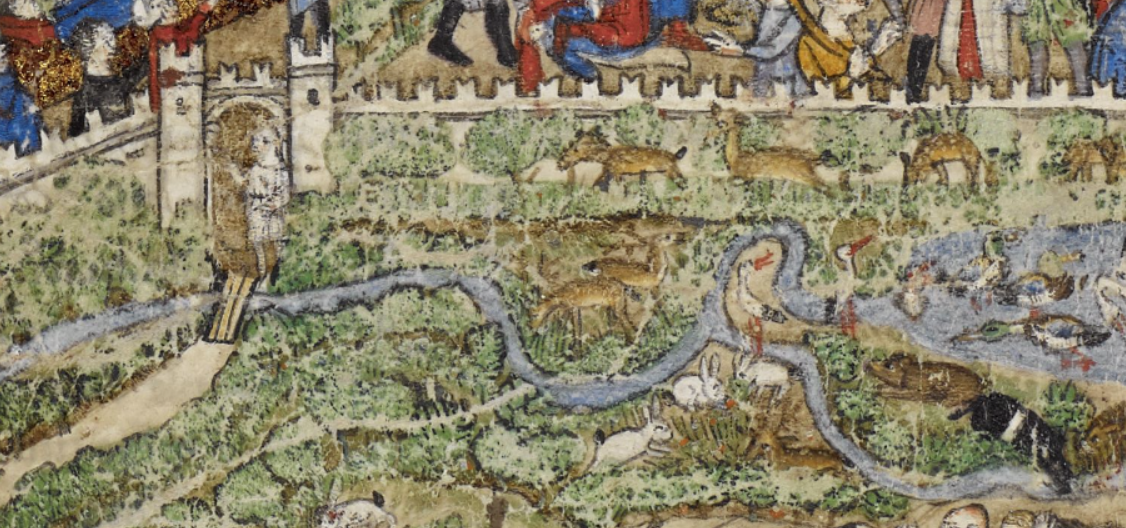

Ensisheim is in eastern France, near the Swiss and German borders and I was intrigued by a more humble drawing of the meteorite event. People are pointing, birds are knocked out of their flight by the boom from the “thunderstone”, and animals scurry for their dens:

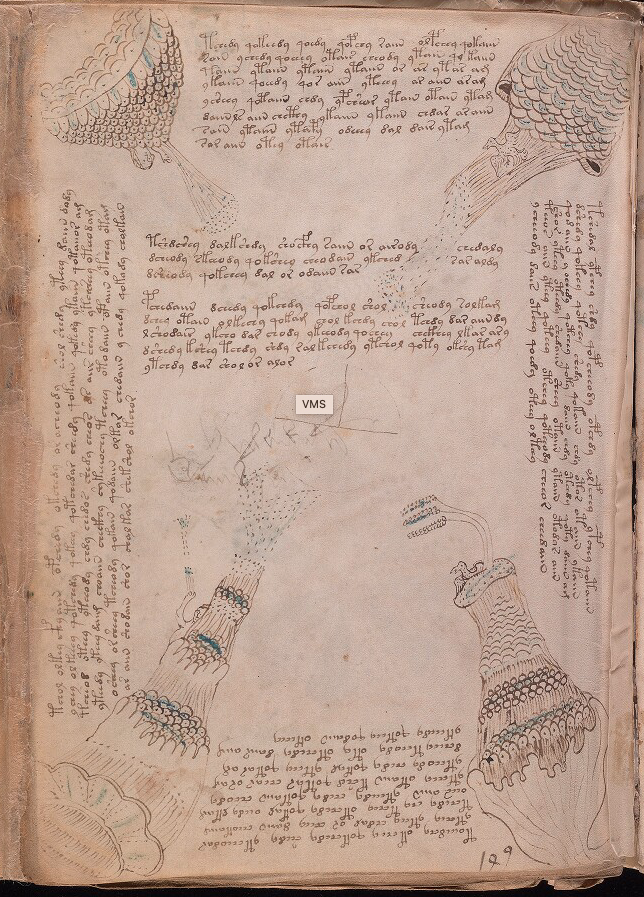

This illustration reminded me of the full-page drawing in the VMS that has multiple textures and emanations seemingly shaking the foundations of the earth. There is a person hiding or peeking out from behind a tor, a bird flapping by a cloudlike formation in the upper-right and another with wings raised as if to fly sits on the tor below.

I’ve already blogged about possible interpretations of this folio, and the Ensißhein meteorite event is probably too late to have influenced the VMS, but the fact that the folio has a narrative feel, like the Ensesheim drawings, makes me wonder if it chronicles a natural or mythical cataclysm:

Another meteorite hit the earth near Basel, Switzerland, in the 16th century but I wasn’t able to find any illustrations of similar events before the Ensisheim meteorite. There are some earlier drawings of “comets”, however, and since the word “comet” was used rather imprecisely at the time, maybe some of these sitings were meteorites.

U. dall’Olmo, in the Journal for the History of Astronomy, 1978, Vol. 9 searched medieval records for celestial events and describes a spectacular meteor shower in southern Italy in 1387 that was said to light up the sky. Three decades later, a meteor appeared after sunset and split into three while traveling west to east. If the VMS drawing has anything to do with meteor events, maybe it chronicles something earlier than the thunderstone of Ensesheim.

More on Portal Gates

Getting back to portal gate designs… the Helpoort gate in the Netherlands is a 13th-century entrance portal with an arched entrance, two round towers, and an asymmetric cone-shaped roof. I don’t know how old the finials are (they tend to wear and be replaced) but globe and flag finials were common in the middle ages.

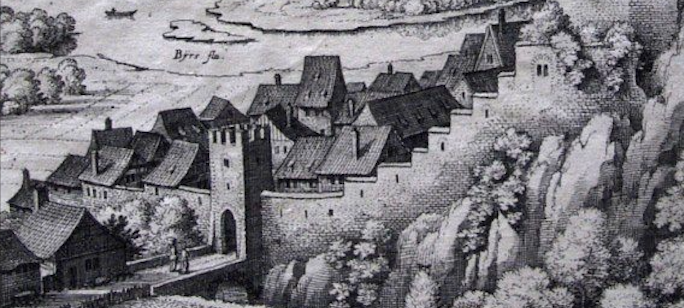

In the 17th century, Reims was drawn with two saddleback portal gates flanked by a pair of round towers with cone roofs. A series of round towers, some roofed, some not, are spaced at intervals along the city wall.

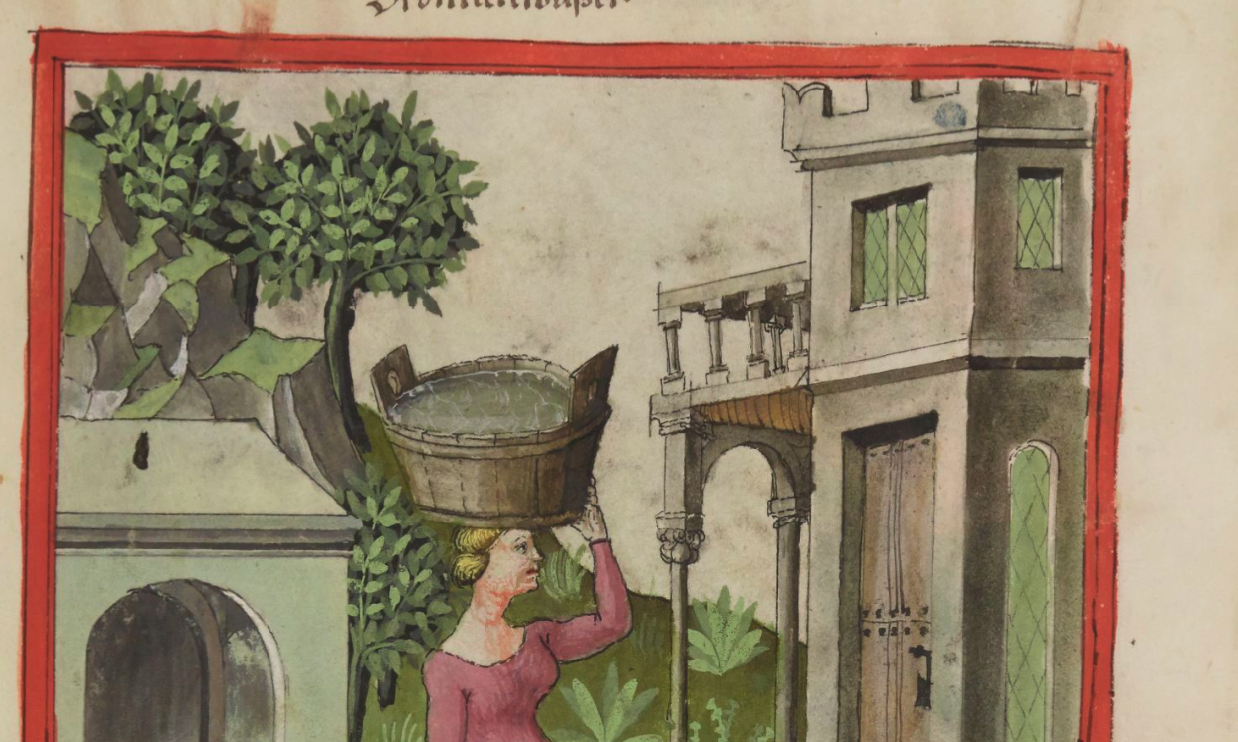

When Adam and Eve are driven from Paradise in this manuscript from Switzerland, we see them exiting through the portal gate roofed with a hip gable and two flag finials:

Roofs in the VMS “Rosettes” Folio

There are a number of corner towers and portal towers on the VMS “map” folio. The drawings are very tiny but still recognizable. The roofs are consistent with the styles of the towers and with each other.

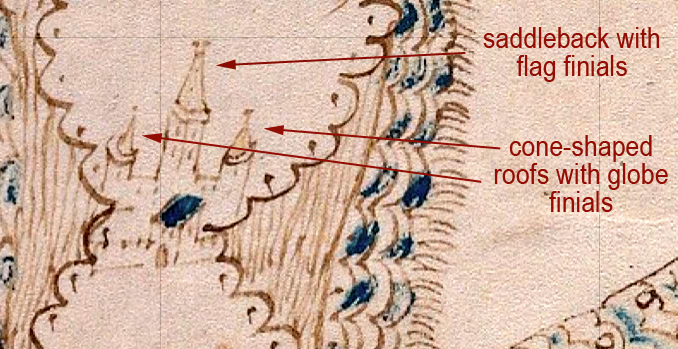

On the lower side of the top-right rosette, there is a simple square tower facing the rosette, but the tall tower is probably also a portal tower that faces the pathway on the other side (imagine standing on the rosette and looking toward the “path” as though you are seeing it from the back). The central tower roof is a gable with flag finials facing outwards, a typical saddleback, flanked by cone roofs with globe finials (I think the finial on the right is probably a smudged globe finial, but it may possibly be a flag finial):

On a circular wall within the rosette, possibly at the top of a steep area, there is another saddleback tower apparently attached to the wall, but it doesn’t appear to have a portal opening. It may be a watchtower rather than an entry point.

This one has a hip gable and a pair of finials that are so small, it’s difficult to tell if they are flag or globe finials. If it’s a watchtower rather than an entrance tower, they are probably globe finials.

I think it’s very unlikely that the drawing below represents a lighthouse. Lighthouses were generally round and even if they were square near the bottom, as in some of the most ancient, the top was usually round so the signal fires could be seen from multiple angles. All through history, the majority of lighthouses were round or rounded (octagonal) at the top. Even the tower of Hercules transitions from square to octagonal to rounded as one reaches the top.

I have never seen a historic lighthouse with a saddleback roof and, in general, lighthouses were not attached to walls at the tops of hills. More often they were on prominences jutting out into the water closer at sea level, or they were on small islands or rock formations in or near the harbor. This looks like a typical wall-tower:

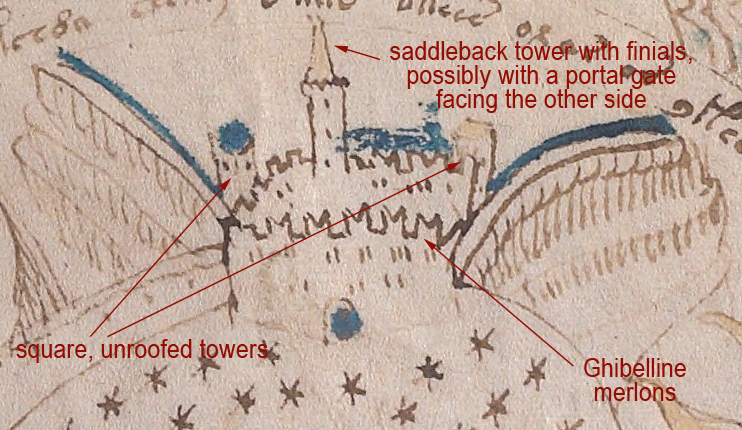

On the same wall, on either side of this tower, there are additional towers that appear to have cone roofs and finials. Moving to the left side of the rosette, facing another “pathway”, there is a wall castle or city with Ghibelline merlons, two unroofed towers, and a tall, narrow hip gable with finials:

Note also that the Ghibelline merlons are not on every side. The merlons on the left are the more common square merlons.

Pointed merlons are found in many areas of southern Spain, and if they are placed in pairs, they superficially resemble Ghibelline merlons, but they are not the same. The merlons on the VMS are straight on the outside and angled on the inside and join without reaching the base. The merlons in Spain are angled on two sides to create a different shape. There are some swallowtail merlons in Spain, but I haven’t found any that existed before the latter part of the 15th century.

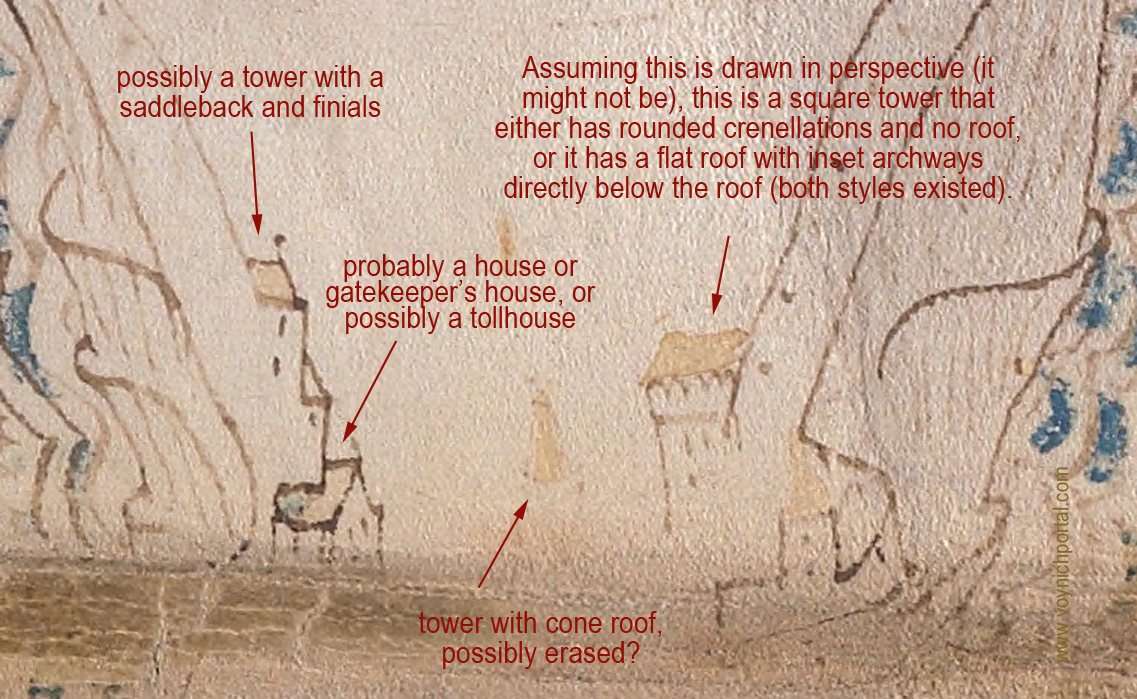

Beyond this compound, to the left, there appears to be a walled pathway with buildings and towers at intervals. On the outsides of the walls are what appear to be steep escarpments, very similar in shape to certain geological formations and also similar to the escarpments created by mining operations. The buildings on the left look like houses and possibly a tower with finials. On the right is a platform tower with crenellations, possibly roofed. In the center is a faint tower with a cone roof that looks like it might have been partially erased:

Mining was quite extensive in the Middle Ages. Silver, gold, and other metals, along with desirable stones such as gemstones, granite, and marble, were so heavily mined that entire mountains were sometimes reduced to foothills. During the process, narrow terraces were often formed. This makes it difficult to know whether the lines that look like escarpments in the VMS are natural or manmade.

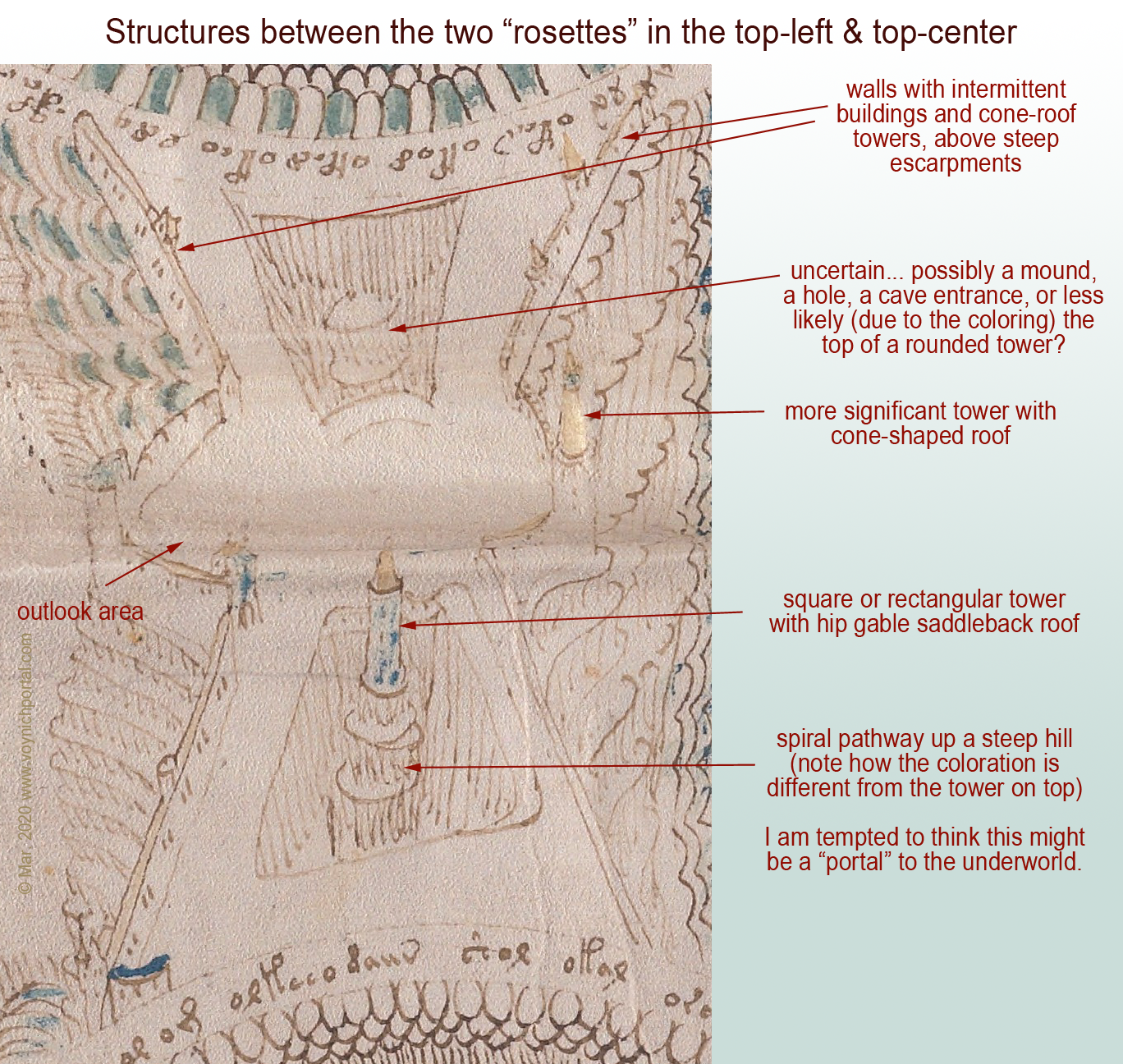

The next section in the top-left is quite detailed and it’s difficult to interpret the structures that appear to be inset into apparent hollows in the pathway:

The blue tower appears to be sitting on a steep tor with a spiral pathway to the top, and is colored to distinguish it from the structures under and around it. For this reason, I am reluctant to call the bumpy thing in the upper hole a building, as it is the same colors and textures as the “dirt” around the lower tower. My best guess at the moment is that the upper “hole” might be a cave entrance or a cutaway in a cliff as was sometimes created in the middle ages, with arched lookout points along the way.

Walls with Buildings

Walls with attached buildings were quite common in the Middle Ages. The way the path widens out where it appears to be steep is fairly common, as well, providing intermittent stopping places and viewpoints.

Tollhouses were installed at regular intervals on major rivers and paths, so the presence of a house attached to the wall might indicate a checkpoint or tollhouse.

At the bottom of the folio, we see a long wall of Ghibelline merlons, but no towers:

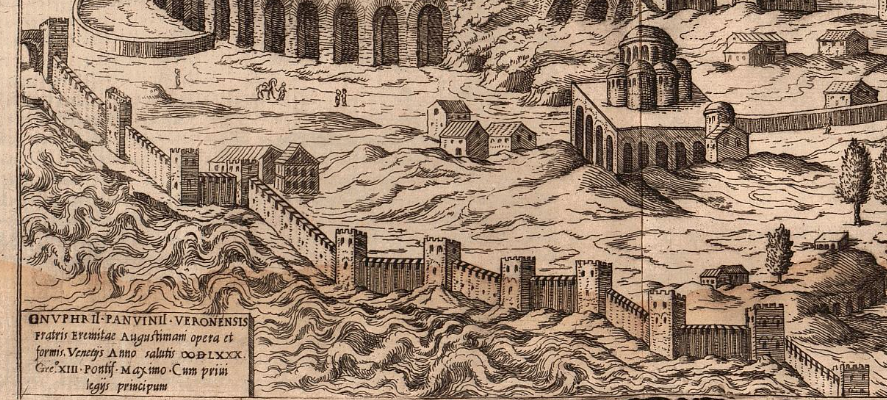

This drawing of a wall in Constantinople, published 1580, has numerous attached towers, but they are shown with flat, unroofed, crenellated tops:

Old paintings of Florence, Italy, have towers similar to those in the illustration of Constantinople, with the exception of one portal tower that includes a low-profile hip-gable roof.

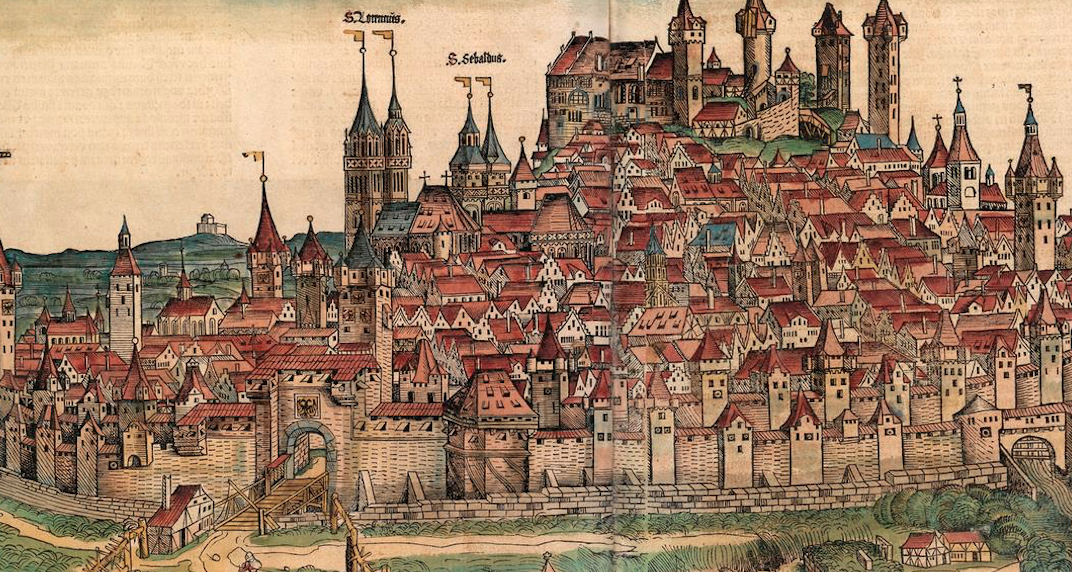

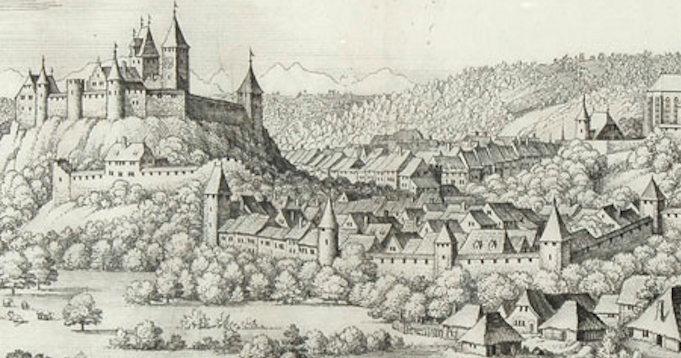

This image of Nuremberg published in 1493 includes numerous cone- and gable-style roofs, several with globe and flag finials:

Burgdorf was drawn very similar to Nuremburg, with a variety of gable- and cone-style roofs. Note the tall tower with the saddleback roof is plainly visible even though trees obscure the gate. The buildings on the hill have flag finials (perhaps more than actually existed at the time but which were not uncommon in Switzerland and can also be found in Thun, south of Bern):

The way the portal-style towers and gates are positioned in the VMS, at significant junctions between landmarks and pathways, makes sense in the context of the Middle Ages, a time when there were many walled cities.

Real or Mythical?

But are they real or mythical? Should they be interpreted as actual places?

The “tower in the hole” has always made me wonder if the illustrator were suggesting a link to the underworld. Oceanus was said to swirl around the earth in nine rings (there are nine circular “rosettes”), which hints at the possibility of myth. When Psyche planned to throw herself off a tower after Aphrodite gave her an impossible task, it was the tower that told Psyche how to get to the underworld and back without losing her life. Is the tower-in-a-hole a conduit between this world and the one below?

Summary

As can be seen by some of the examples in this and other blogs, illustrations of far-off places or mythical events were sometimes drawn with local architecture. The illustrators guessed, or simply drew what they knew. This means that the saddleback portals and Ghibelline merlons might not be literal, they could be symbolic, or simply familiar and thus easy to use.

Regardless of why they were chosen, the consistency among them suggests awareness of architectural styles that were common in the region stretching from Bohemia in the east and the Alsace and eastern France in the west, and from Bavaria in the north and Lombardy and the republic of Genoa in the south. If the “rosettes” folio is a map, it might represent this region and it might not, but even if it doesn’t, the illustrator chose elements that betray a specific familiarity with the southern portion of the Holy Roman Empire.

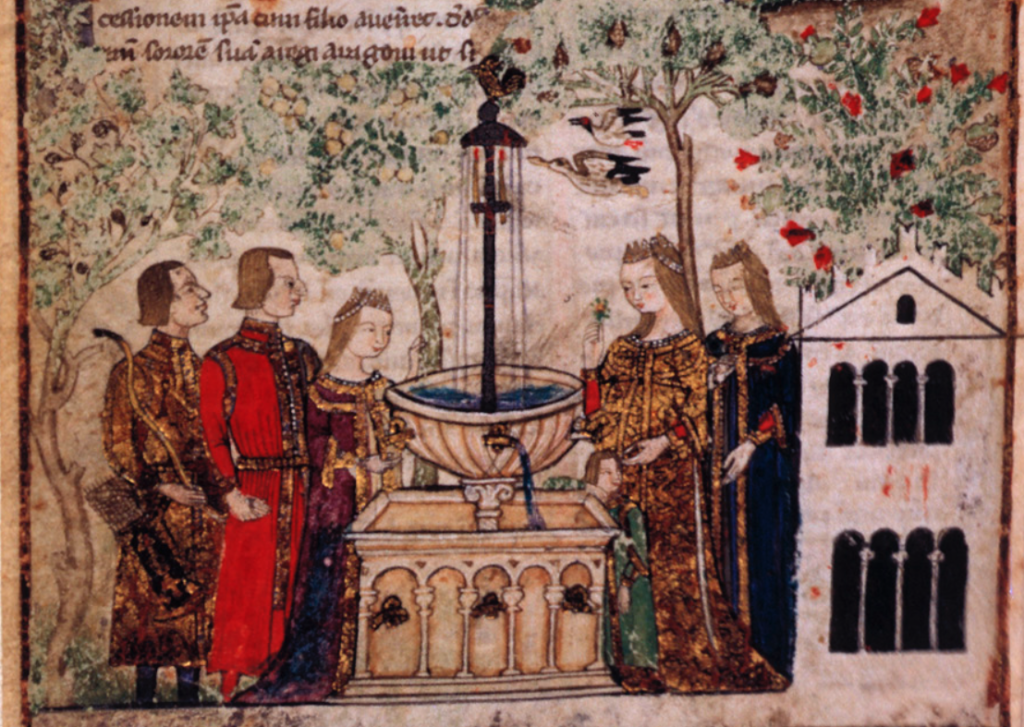

You might notice that the picture to the right has a saddelback portal flanked by two round towers with cone-shaped roofs, similar to the first VMS castle illustrated above. It could easily be a coincidence, but for the record, the image is from a chronicle of the crusades penned in the 1460s (Bibliothèque de Genève Ms. fr. 85).

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 25 March 2020 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved