I wasn’t sure what to title this blog because it’s not clear what is going on at the bottom of Folio 66r. Is this a murder mystery? Is that a dead body?

I wasn’t sure what to title this blog because it’s not clear what is going on at the bottom of Folio 66r. Is this a murder mystery? Is that a dead body?

Audrey the ailing plant begs for blood in Little Shop of Horrors, courtesy of Warner Brothers, 1986.

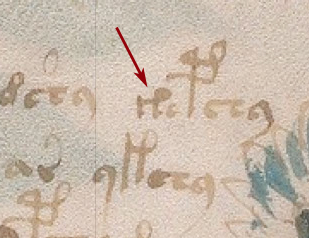

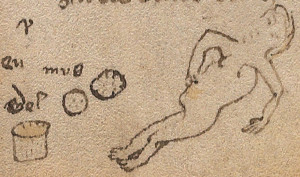

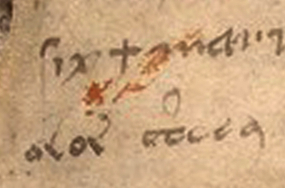

In fact, Folio 66r is unusual in many ways. Not only is there a mystery pic at the bottom, with some altered text beside it, but the upper left is full of character glyphs that differ from the majority of the text in both shape and position.

Since there are enough head-scratchers on this page to fill several blogs (perhaps several papers), I’ll start with the image and marginal text at the bottom. It might be a mistake to describe it out of context with the text at the top but, since we haven’t deciphered the big block of text, maybe it’s okay to start with the picture.

What is Going On Here?

It’s possible the Voynich Manuscript is a medical text, with a particular emphasis on women’s health. It is full of plants (plants were medicine in the Middle Ages), nude ladies bathing, women’s cycles, and stylized drawings of internal body parts.

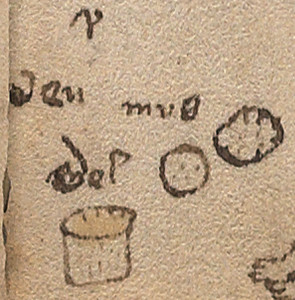

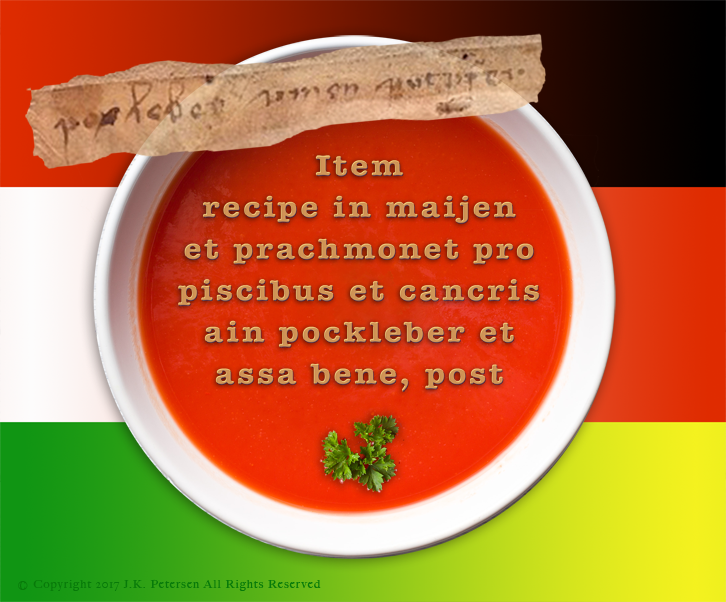

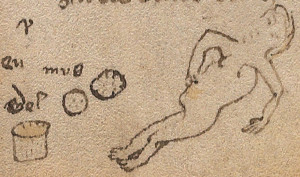

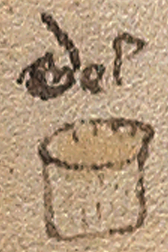

On Folio 66r, there is a figure in the lower left, presumably female, with a distorted stomach and an oddly curved back. The back might be some excess poundage or maybe some swelling. It may also be an example of weak drawing skills.

The bottom of the stomach is sticking out in an oddly irregular way, compared to the round bellies in other parts of the manuscript. Nearby are three objects: a spotty irregular mass that resembles a sponge but could be almost anything, a rounder spotted object (a lid? a rock? a rounded tuber?), and what might be a container of some kind (it has lines on it like a woven basket, but it’s very hard to tell—it could be a bucket, a cup, or a chamber pot).

Dead or Alive?

Is this prostrate figure a corpse? Or a figure looking toward us, with eyes open? Is it the face of distress or someone lying on a board waiting to be examined? Is she pinching her stomach? With so few details, it’s difficult to tell.

The face of the woman is faded, as though the quill were running out of ink, but it looks like the eyes might be open, and her right arm seems to be pinching and pulling the stomach, so maybe it isn’t a dead body after all—it might be someone in distress. Assuming for the moment that the prostate figure is alive (and female), what could be causing a problem?

- Stomach ache?

- Dysentery? (King Henry V is said to have died of dysentery in 1422)

- Injury?

- Appendicitis?

- Menstrual cramps?

- Childbirth pains?

- Post-partem distress?

I hate to suggest abortion, because it’s always a touchy subject, but we have to consider this possibility. In medieval times, many girls, from peasants to royalty, were sold off as wives in their mid-teens and sometimes endured fourteen or more pregnancies when they scarcely had food to feed two or three mouths and, if their husbands were soldiers, the breadwinner was frequently away from home burning and pillaging, leaving the women to cope with the household and children alone.

They were turbulent times. People were hung, dragged behind horses, burned at the stake, castrated, and drawn and quartered in the public square, where even the smallest child could sit and watch. Explicit examples of these procedures were recorded by 15th century artists such as Giovanni Boccaccio (right).

They were turbulent times. People were hung, dragged behind horses, burned at the stake, castrated, and drawn and quartered in the public square, where even the smallest child could sit and watch. Explicit examples of these procedures were recorded by 15th century artists such as Giovanni Boccaccio (right).

Given this attitude toward life and death, abortion was a very common occurrence and abortifacient plants are mentioned in many herbal manuscripts, sometimes euphemistically as, “a plant that encourages courses” (“courses” meaning menstrual bleeding).

Maybe the other objects can shed some light on what’s happening to the recumbent figure.

Perhaps the explanation is simple—the naked damsel might have a tummy ache. The irregular mass could be an unfortunate consequence of diarrhea, or it might be the afterbirth following pregnancy and childbirth. Maybe it’s a tumor or cyst (surgery has been around since Egyptian times and even Caesarian sections were performed in centuries past).

Perhaps the explanation is simple—the naked damsel might have a tummy ache. The irregular mass could be an unfortunate consequence of diarrhea, or it might be the afterbirth following pregnancy and childbirth. Maybe it’s a tumor or cyst (surgery has been around since Egyptian times and even Caesarian sections were performed in centuries past).

Note that images of children are conspicuously absent in the VMS. If you consider it’s full of cavorting naked women and women in various stages of pregnancy, it’s surprising there are no offspring. It does show a few girls on the cusp of puberty in the zodiac wheels, but they are included to show the beginning of the maturation process and very young children are not shown.

Men are not completely absent from the VMS. There are illustrations of men both clothed and naked, and details of body parts engaged in ejaculatory activity, as in the left margin of Folio 77v. If the drawing on 66r is a reference to childbirth, it would not be out of place.

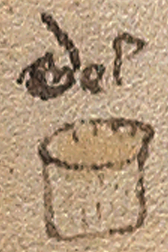

What’s the Yellow Stuff in the Bucket?

If you look closely, you’ll note that the inside of the bucket (assuming it’s some kind of container) is a pale golden color. Maybe it was painted this way to make it look three dimensional and there’s nothing in the bucket, but there’s a splotch on the woman’s stomach that seems to match, so perhaps there’s a connection between the two.

If you look closely, you’ll note that the inside of the bucket (assuming it’s some kind of container) is a pale golden color. Maybe it was painted this way to make it look three dimensional and there’s nothing in the bucket, but there’s a splotch on the woman’s stomach that seems to match, so perhaps there’s a connection between the two.

It’s difficult to tell from a digital scan if the spot on the stomach is a natural discoloration in the page (it matches the ragged yellow edge of the parchment on the right) or is intended to refer to the contents of the bucket, but let’s assume it was painted there.

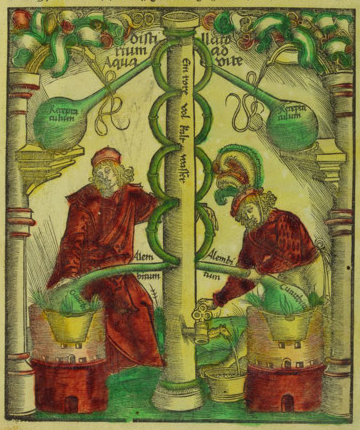

Urine chart illustrating different possible colors, Wellcome Library, London. Epiphaniae medicorum, Pinder, Ulrich, 1506

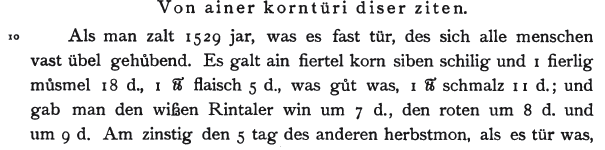

Could the substance be a salve to relieve distress, or a reference to something going on inside the belly? Is the yellowish color urine?

Diagnosis with urine specimens was a hot topic in medieval circles. Many herbal compendiums include wheels showing beakers filled with liquid in a range of colors. When urine was reddish, dark brown, or even purple, it was assumed some disease or internal malfunction might be present, but the substance in the VMS bucket is the color of healthy urine so it seems unlikely it relates to someone lying down, pulling on her belly.

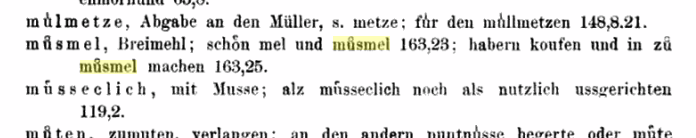

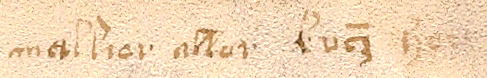

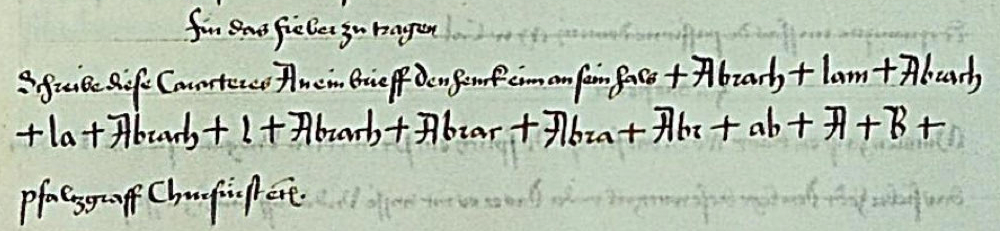

Maybe it’s not urine; maybe it’s something used to treat disease or injury. Medieval pharmaceutical recipes often recommended mixing oil, wine, or honey with herbs for making ointments for external use, or potions for internal use. Assuming white wine rather than red, all of these might be a pale yellowish color. So how do we know? There might be a clue. If you look at the text above the container (which has been altered, but which may have originally read “mel”), then you have the word for honey that was commonly used in herbal manuscripts.

Maybe it’s not urine; maybe it’s something used to treat disease or injury. Medieval pharmaceutical recipes often recommended mixing oil, wine, or honey with herbs for making ointments for external use, or potions for internal use. Assuming white wine rather than red, all of these might be a pale yellowish color. So how do we know? There might be a clue. If you look at the text above the container (which has been altered, but which may have originally read “mel”), then you have the word for honey that was commonly used in herbal manuscripts.

Which brings us to the text. Can the text help us understand the puzzling image?

Did the Right Hand Know What the Left Hand Was Doing?

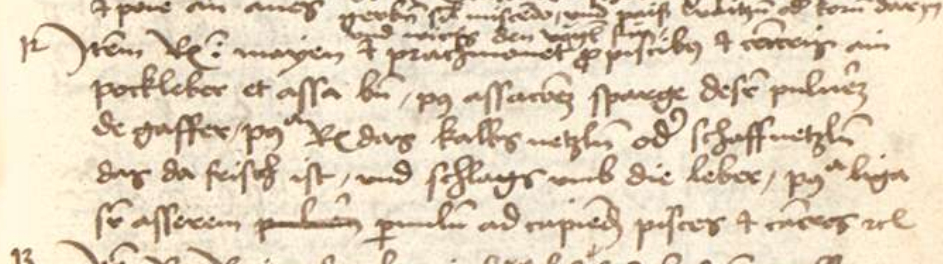

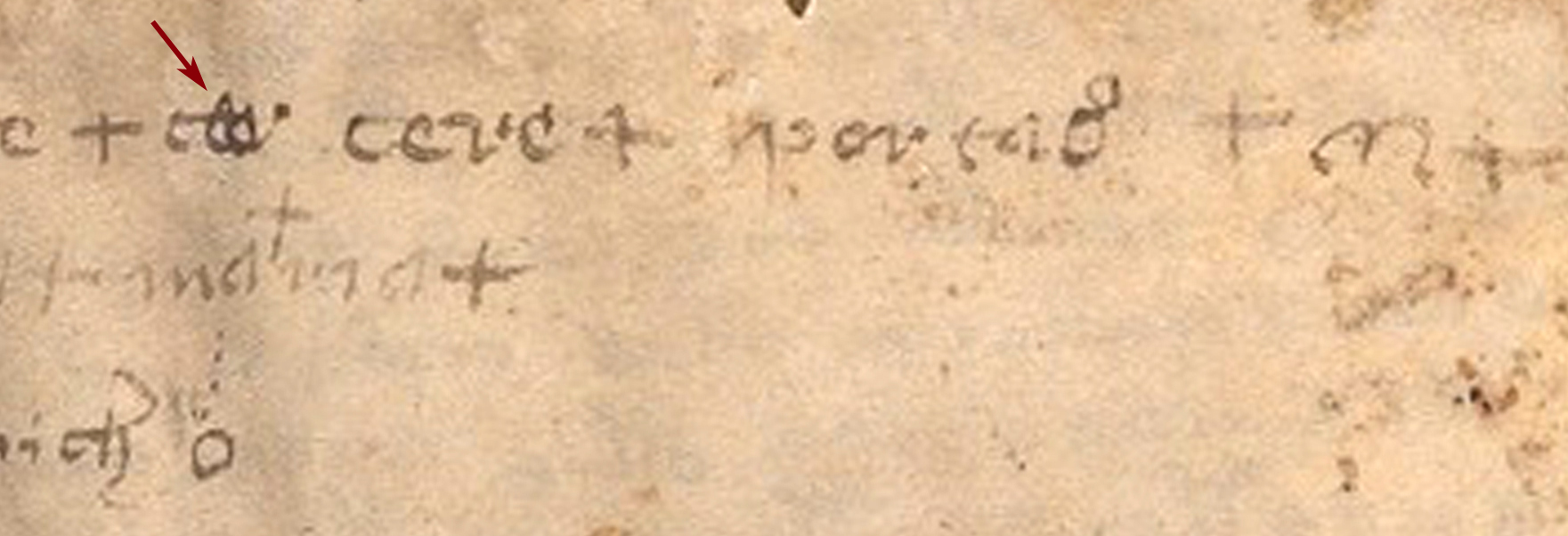

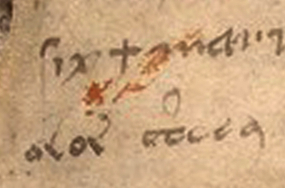

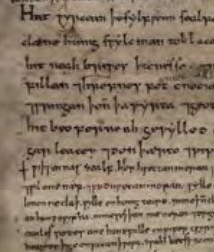

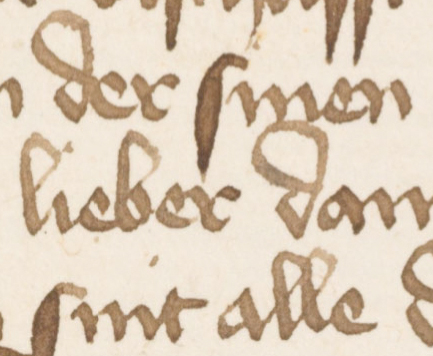

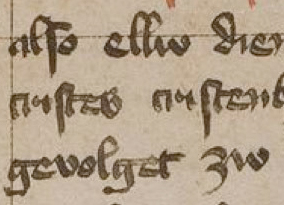

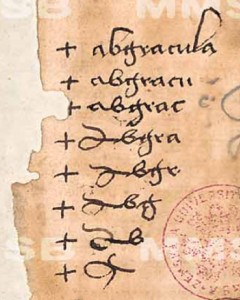

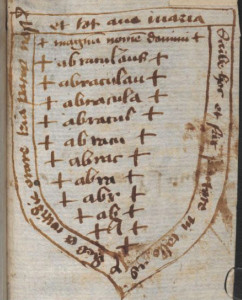

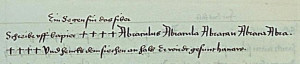

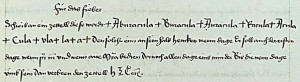

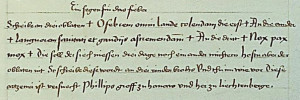

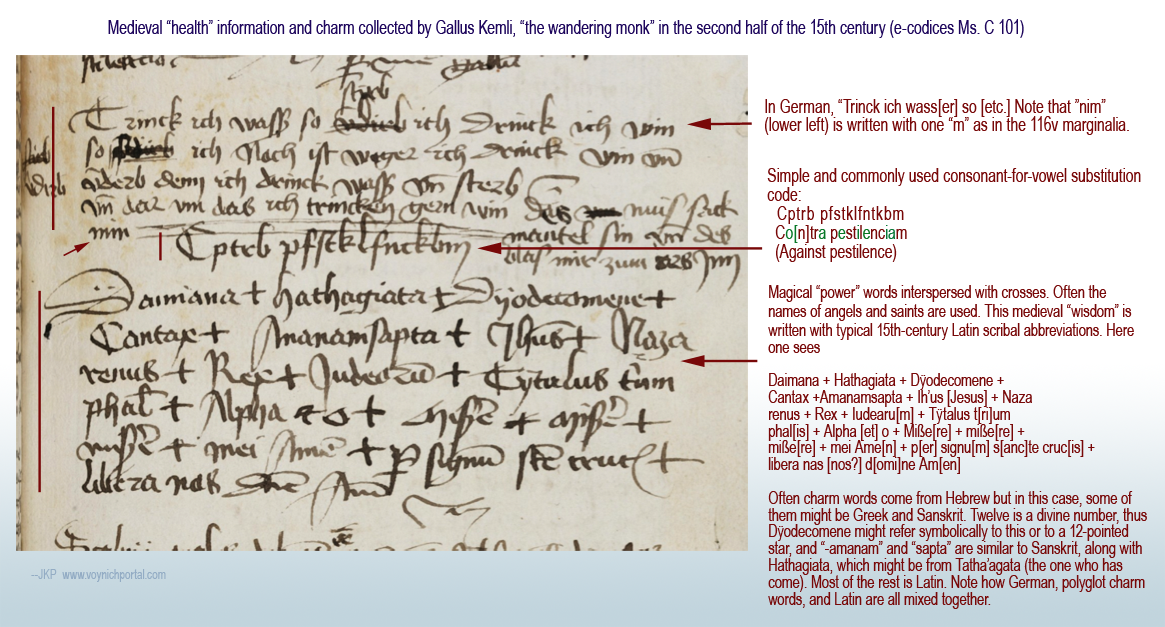

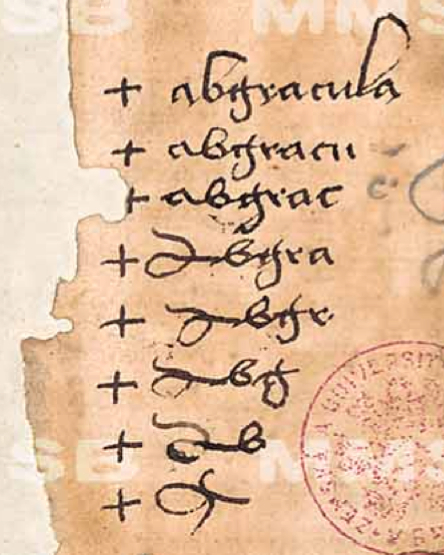

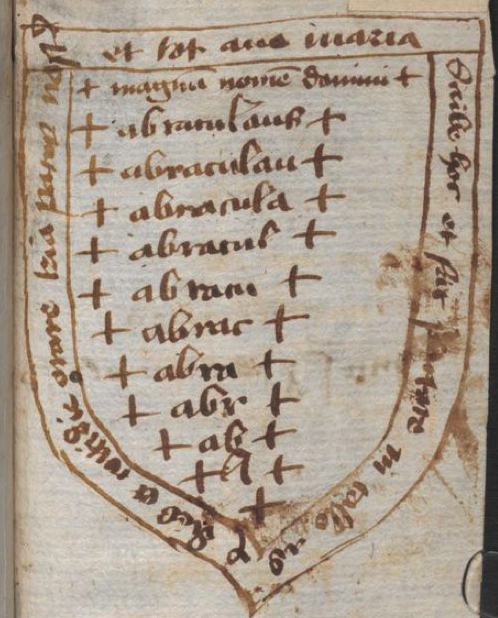

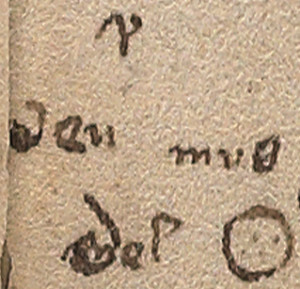

There are a few places in the Voynich Manuscript where we see marginal text in a Gothic cursive hand, separate from the main text. Normally Voynichese and marginal text are not combined, but there are some instances where it happens, as on Folios 116v (right) and 17r. This only deepens the VMS mystery. Do different hands represent different people? Or did the VMS scribe write the marginal notes as well?

There are a few places in the Voynich Manuscript where we see marginal text in a Gothic cursive hand, separate from the main text. Normally Voynichese and marginal text are not combined, but there are some instances where it happens, as on Folios 116v (right) and 17r. This only deepens the VMS mystery. Do different hands represent different people? Or did the VMS scribe write the marginal notes as well?

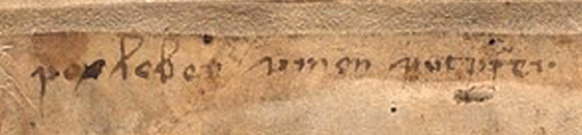

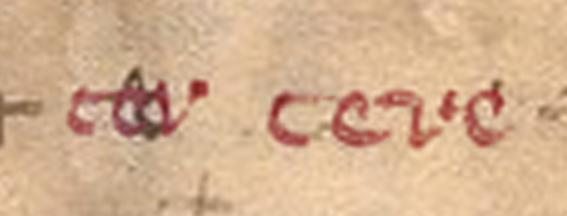

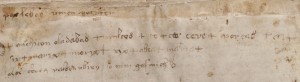

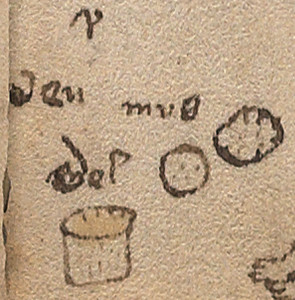

On 66r, the two forms of script are not intermingled, but there are definitely two different scripts—Voynichese above the drawing, and Gothic cursive (or something close to it) above the bucket. We don’t know which was added first, but the drawing was possibly there before the Voynichese was added, as the tail of the glyph next to the head looks like it has been shortened so the tail doesn’t clobber the head.

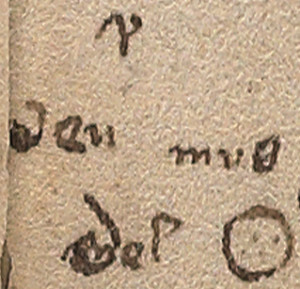

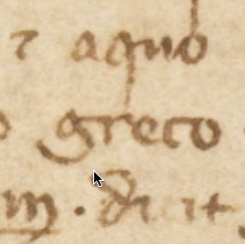

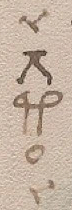

Looking at the text on the left, I can’t interpret the lonely letter at the top because it’s halfway between an “r” and a “v” as they were written at the time, or perhaps it’s the Greek ypsilon.

Looking at the text on the left, I can’t interpret the lonely letter at the top because it’s halfway between an “r” and a “v” as they were written at the time, or perhaps it’s the Greek ypsilon.

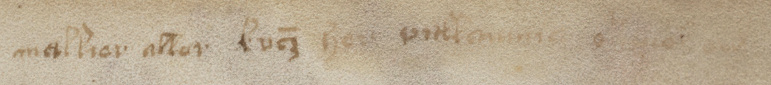

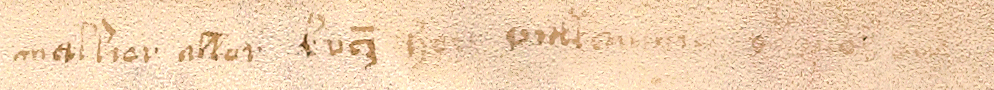

The text by the bucket is similar to the Germanic hand on Folios 17r and 116v.

As with the other marginal texts in the VMS, this one is difficult to read, but ignoring the over-writing, it looks like “ven muß mel” in Germanic or a mixture of Germanic and Latin.

As with the other marginal texts in the VMS, this one is difficult to read, but ignoring the over-writing, it looks like “ven muß mel” in Germanic or a mixture of Germanic and Latin.

It’s tempting to interpret this as “when one should use honey” or “in this situation one must use honey”. This assumes the first letter in the bottom word was an “m” before it was obscured.

In modern German, honey is “honig” but in the 15th century, throughout Lombardy, France, Italy, and Greece, variations on “mel” included meile, melle, meli, etc., and were used to notate honey in herbal documents, plus most scribes knew Latin, in which honey is “mel”. Honey is frequently mentioned in herbal compendiums in combination with Artemisia, Viola, garlic, and horehound. Examples of honey recipes can be seen in Ms. Egerton 747 and many others.

In modern German, honey is “honig” but in the 15th century, throughout Lombardy, France, Italy, and Greece, variations on “mel” included meile, melle, meli, etc., and were used to notate honey in herbal documents, plus most scribes knew Latin, in which honey is “mel”. Honey is frequently mentioned in herbal compendiums in combination with Artemisia, Viola, garlic, and horehound. Examples of honey recipes can be seen in Ms. Egerton 747 and many others.

What about that first word of “ven muß mel”? Could it be something besides an old Germanic reference to “when”? Is it possible it relates to the old Anglo-Saxon word for swelling which is “wen” or “wenn”? Then the phrase might mean, “honey should be used for a swelling” (note that in German, a “w” is pronounced as a “v” in English).

Honey as Traditional Medicine

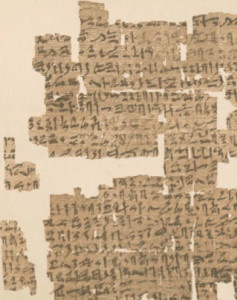

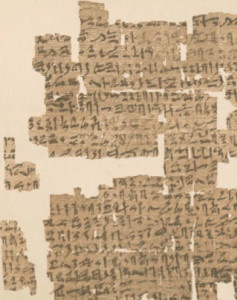

Honey was used as traditional medicine at least as early as Egyptian times. In the Ebers Papyrus of c.1550 BCE, which was found between the legs of a mummy, are passages about women’s health, with honey mentioned as a base for salves for treating wounds and other disorders.

An even earlier document, called the Kahun Gynecological Papyrus, dating from c.1800 BCE, is specifically devoted to women’s health.

An even earlier document, called the Kahun Gynecological Papyrus, dating from c.1800 BCE, is specifically devoted to women’s health.

Here are some examples of medical recipes from the Ebers and Kahun papyri related to complaints of the belly, or conception and childbirth:

- A paste of honey and yellow ochre was suggested for intestinal or urological complaints.

- “For the evacuation of the belly: Cow’s milk 1; grains 1; honey 1; mash, sift, cook; take in four portions.”

- “To prevent conception, smear a paste of dates, acacia, and honey to wool and apply as a pessary.”

- Another recipe for contraception was a paste of crocodile dung, honey, and sour milk (hopefully the document also includes a treatment for crocodile and leech bites).

- “hin of honey, sprinkle over her womb, this to be done on natron bed”

Herbal traditions in ancient Rome included honey as a barrier method to contraception. Mixed with sodium carbonate to create a paste, it was used to cover the cervix.

Medieval Use of Honey

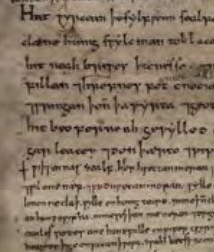

In the Wellcome library there’s an interesting 11th century folio that was preserved in a book from the 9th century, in which medical recipes have been added in more than one hand, apparently by monks. Here is a translation of a section that mentions honey as a treatment for “wenns” (which can mean either tumors or swellings):

To make yourself an ointment for tumours [wenns], one shall take pure honey, such as is used to lighten porridge, boil it to almost the thickness of porridge; take radish, elder, wild thyme, cinquefoil, pound them as well as you can; and when it is almost done mix in a good measure of garlic and put to it as much pepper as you think.

To make yourself an ointment for tumours [wenns], one shall take pure honey, such as is used to lighten porridge, boil it to almost the thickness of porridge; take radish, elder, wild thyme, cinquefoil, pound them as well as you can; and when it is almost done mix in a good measure of garlic and put to it as much pepper as you think.

A salve against tumours, water cucumber, a handful of spearmint, dittany, woodwax, mulberry; boil in malt-ale; squeeze through a linen cloth, boil in honey-droppings; take then clean spring barley, grind (it) in a handmill; then take madder, dry it in (an oven); grind a handful of red-cabbage seed in a peppermill; boil all together, not too hard. Use it three times a week, as is most convenient.

This salve is good for tumours and for the bleeding of piles. But it should be stirred up, lest it should be spoiled.

Summary

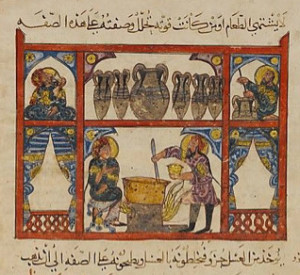

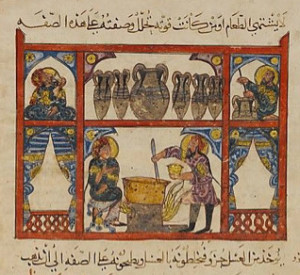

Preparing honey in an Arabic version of De Materia Medica from c.621 AD

The use of honey for belly complaints or gynecological purposes has been passed down for thousands of years and was not new to medieval physicians and midwives. Oils and wines were also used for tonics and salves, but it’s harder to reconcile those with the word “mel” appearing above the bucket.

We don’t know if the label in another hand accurately represents the drawing (or possibly a translation of the text above the drawing). Maybe the person who wrote the marginal notes was guessing, just as we are, but if it’s the same writer who added notations to f77r and f116v, it’s possible he had some knowledge of what was in the VMS.

Until we can decode the rest of the text, the purpose and contents of the bucket will remain a mystery and the status of the woman uncertain, but it’s reasonable to think it might be honey, and that’s a more pleasant note to end on than some of the other possibilities.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2016 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved