It’s almost impossible to search through medieval manuscripts without seeing the Ex Libris of the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits) on the fly leaves of books. The Jesuits also feature prominently in the provenance of the Voynich Manuscript, as there was correspondence among them about a mysterious unreadable book, and it was Jesuits who purportedly sold the manuscript to Wilfrid Voynich.

A commemorative gold piece featuring the five-petaled rose and diagonal bars of Wilhelm of Rosenberg was minted to honor his investiture as a member of the Order of the Golden Fleece in 1585. [Photo by Matthias Kauerhase in the Národní museum, Prague.]

The “Societas Jesu” (Society of Jesus) was officially established in the mid-16th century through a commendation by Pope Paul III. After a limit on membership was lifted, in 1550, Jesuits rapidly spread across the globe.

One of the first missions of the Society of Jesus was to establish schools. The Jesuit college at St. Clement’s in Prague became a university in 1562. In 1566, the college in Moravia did so, as well. In 1572, a college was founded in Brno. A year later, with support from archduke Charles, a college was chartered in Graz and attained university status in 1586.

buy gabapentin online overnight delivery Jesuit Missions and Jakub Horčický

Not to be outdone by Prague to the north and Graz to the south, Wilhelm of Rosenberg (Rožmberk), the nobleman who ruled Krumlov, invited Jesuits to establish themselves in his realm, in 1584, as part of the counter-reformation.

As a result, in 1588, the Jesuits founded the Krumlov school that admitted the young Jakub Horčický, as a poor student with scholastic potential who later became Emperor Rudolf II’s physician and herbalist (and whose name appears on the first page of the Voynich manuscript).

Despite their relatively small numbers, the Jesuits emerged as a unifying force among scholars in the 16th century and provided a regular communications conduit between Rome, Bohemia, and other outlying missions. Their students were not all Jesuits (although a number of them joined the order later in life)—scholarships were given primarily on the basis of need and academic potential, not on the basis of religion.

Georg Baresch (Jiří Bareš), attended the Jesuit college of Prague in the late 1500s and probably knew, or knew of, fellow Bohemian Jakub Horčický, who arrived in Prague in 1598 to study logic and sciences at about the same time Baresch was working toward his baccalaureate. There were about 800 students by this time at the Clementinum (Berenger, Simpson, 2014).

The Jesuits were probably a tight-knit group, being in the minority in Protestant Bohemia, with less than 300 officially recognized in the early 1600s.

The Jesuit Passion for Books

Libraries were an important aspect of Jesuit schools, and donations were sought to populate the shelves. The Clementinum library became the third largest of all the Jesuit libraries:

In 1562, the Clementinum college became a university and inherited a number of manuscripts that had come to St. Clement’s from the Celestine monastery of Oybin (about 150 km north of Prague). Jakub Horčický moved to Prague to study at the Clementinum in 1598. The University of Prague library, which originated sometime around 1366, had its holdings turned over to the Jesuits and incorporated into the Clementinum library in 1622. [Image courtesy of Bruno Delzant, Wikipedia]

By the mid-1700s nobleman are known to have bequeathed entire libraries to the Jesuits, and by the time the Jesuit holdings of Krumlov, a relatively small town, were transferred to Prague, in the late 1700s, there were enough books to fill 44 cases [

encyklopedie.ckrumlov.cz]. Unfortunately, details of the collegiate library in the 1500s are scanty, so it’s difficult to know whether the

Voynich Manuscript might have passed through Jesuit hands in Krumlov.

VMS correspondence is not explicit enough to tell us if the Voynich Manuscript was in Jacobi Horčický’s/Sinapius’s hands around the time that Rudolf died, but I’ve often wondered if Sinapius, or one of his Jesuit colleagues (many of whom were interested in herbs), brought the manuscript to Prague rather than the oft-cited John Dee or Edward Kelley (or someone else who purportedly sold it to the emperor).

If we go back a few years, there are a number of possibilities…

Champion of Catholicism in the 16th Century

British Library: print of Edmund Campion, published in 1631.

Edmund Campion (1540–1581) was the son of a London bookseller, and deacon of the Anglican church. His eloquence impressed everyone, and he became a patron of Lord Dudley, with the opportunity of living a pleasant life, but Campion was uneasy in his conscience, a Catholic at heart, and left England for Ireland. Suspected of being a papist, he fled Ireland and his belongings were apparently confiscated. He made it to France and continued by foot to Rome, and became a Jesuit in 1573.

Thereafter, he traveled through Moravia, was ordained as a priest and became a professor at the Jesuit college in Prague.

As the son of a bookseller, it’s possible Campion had an eye for books. His parents hoped he would apprentice as a merchant, perhaps to help in his father’s business, but the boy was more interested in matters of the soul. Nevertheless, given the Jesuit passion for learning, it’s possible Campion picked up books along the way. If he did, some may have ended up in his father’s shop or in the hands of his Jesuit colleagues and friends.

Campion’s comfortable life as a college professor ended when tensions rose between Protestants and Catholics and he was summoned to Rome. From there, he was sent on an evangelistic mission to England, traveling in the guise of a jewel merchant, in 1580.

He was soon captured and given a stern admonition, and then released and treated as a gentleman, but Campion was resolute—he refused to be won over, and continued his campaign of conversion with unflinching ardor. After writing and distributing materials denouncing the Queen’s religion, in 1580, he became a hunted man and was captured for sedition, imprisoned in the tower of London, tortured, found guilty of treason, and executed, in 1581.

More Connections…

Campion’s father, the bookseller (and perhaps Campion himself), would surely have been known to John Dee. Dee was born in 1527, not far from London, when the elder Campion was probably in his teens or twenties, and Dee ardently collected books wherever he could find them and probably made many trips to Paternoster Row, where Campion’s bookstore was surrounded by other booksellers and publishers.

Olbracht Łaski, Prince Albert Lasky, who hosted Dee and Kelley before they moved to Prague. [Image courtesy of Jan Matejko, Wikipedia]

Philip Sydney, an English poet and diplomat, accompanied Prince Albertus Laski (

Olbracht Łaski/Albert Lasky) on some of his sojourns around London and may have helped promote the meeting between Lasky and John Dee. Dee was formally introduced to Lasky in the chambers of Campion’s former patron Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester, in May 1583. Sydney had also known Edmund Campion at Oxford, and met with him in Prague.

Three months after meeting Lasky, Dee packed up his family and moved, with Edward Kelley and Kelley’s wife, to Krakow and, about a year later, to Prague, the capital of the Holy Roman Empire.

Dee apparently did not impress Emperor Rudolf II and failed to secure patronage as a court mathematician. Eventually, Count Rožmberk provided him a place to stay in Třeboň, where he lived from 1586 to 1589. Třeboň is less than 50 kilometers northeast of Český Krumlov (see map above), so there’s a possibility Dee visited the Rosenberg residence in Krumlov, and perhaps saw the Jesuit library. He may even have crossed paths with the young Jakub Horčický who was four years older than Dee’s son Arthur.

Dee was more interested in collecting books than selling them and his diaries don’t mention anything we can definitely link to the VMS. The various mystery texts connected to Dee have been identified by historians as the Book of Soyga and various notes authored by Dee and Kelley related to the angelic language eventually called Enochian.

In contrast to Dee, Kelley would probably sell a book in a heartbeat if he could talk it up and get a good sum for it, so it’s possible Kelley or Dee conveyed the VMS to the emperor, as has been suggested, but the possibility that the Voynich Manuscript reached Prague through the Jesuits (or by other means), rather than directly through Dee or Kelley, should also be considered.

Jakub Horčický, tended botanical gardens and trained under an apothecary and distiller, and thus had a personal interest in both plants and alchemical processes. In mid-life he reaped a financial windfall from sales of his elixir and might have acquired a book of plants independently of the emperor. As a successful herbalist, distiller, and entrepreneur (so successful he ended up lending money to Rudolf II) perhaps Jacobi de Tepenecz was entitled to put his name on the VMS, and the “600 ducats” recorded in the letter from Marci was paid for something else.

The New Regime

It’s not unreasonable to think that Jakub may have snitched Rudolf’s book when Rudolf died, but it’s also possible Horčický was legally entitled to the Voynich Manuscript. If so, the secrecy surrounding the mysterious book in Jesuit correspondence might have less to do with it being contraband, than its appearance as a book of the occult (“black arts” were banned at the time), or possibly its immodest contents (by 16th-century standards). There are many possible reasons Horčický’s name was on the manuscript and was later expunged.

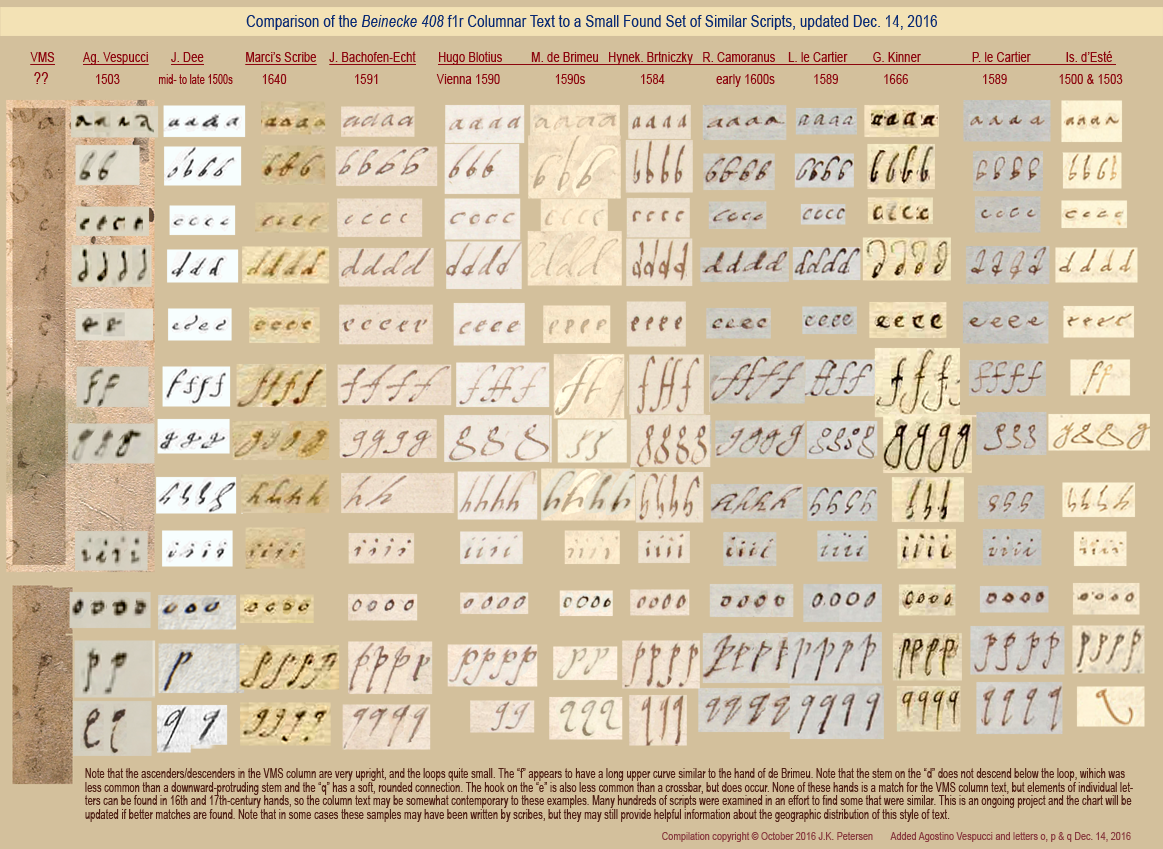

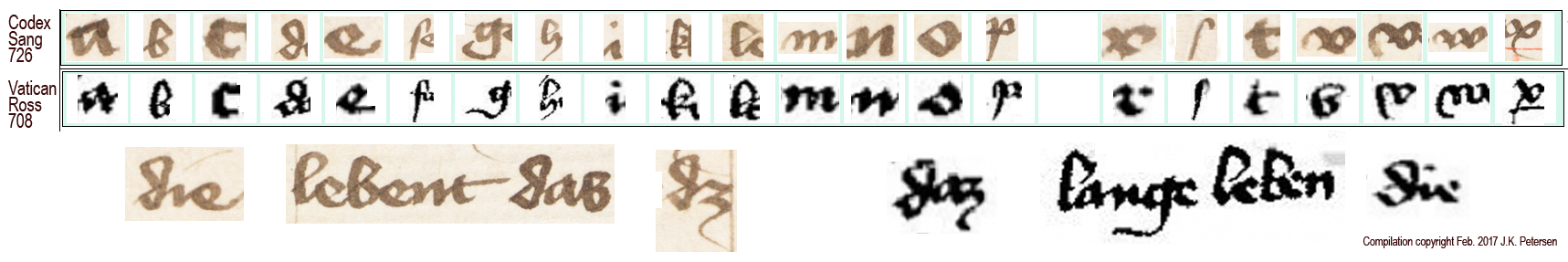

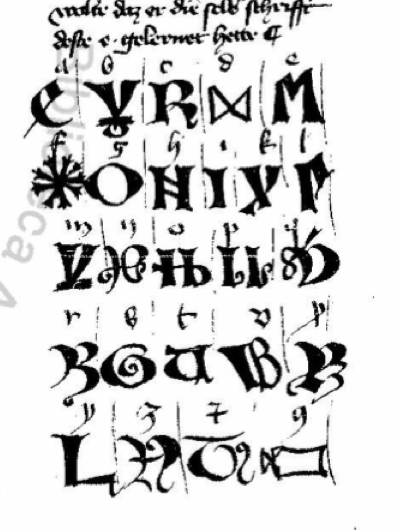

Before trying to decide whether John Dee sold the VMS to the emperor, let’s re-examine the handwriting in the VMS.

The Role of Paleography in Unraveling History

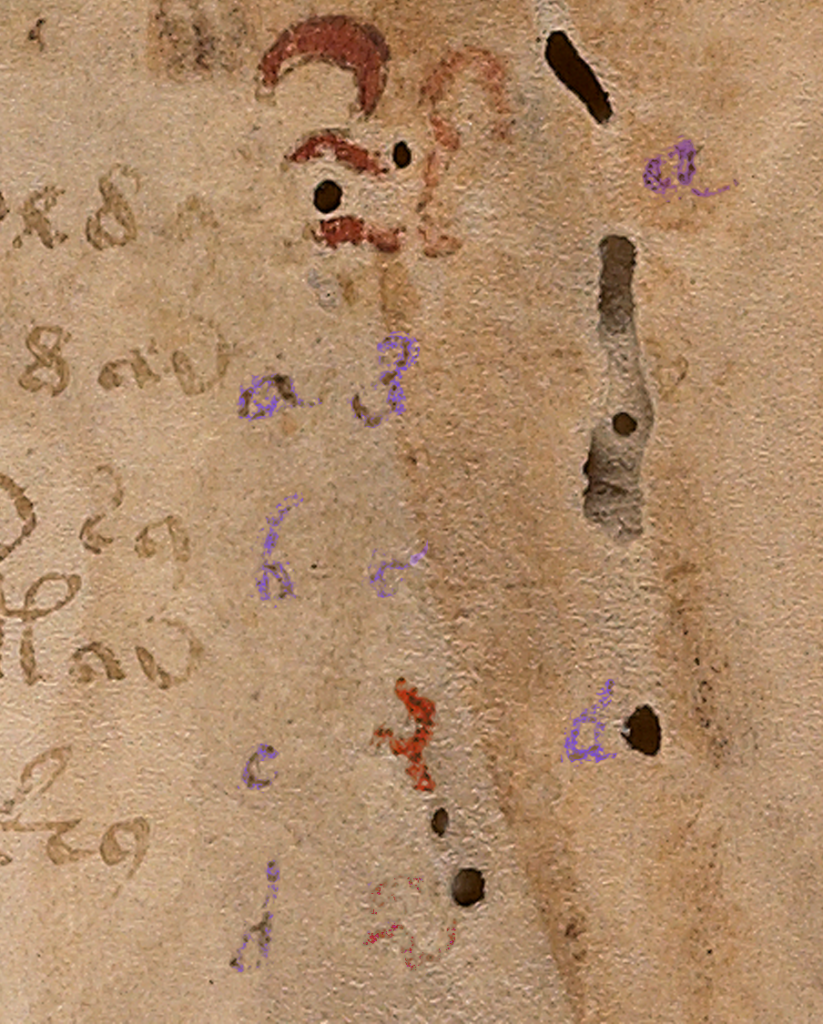

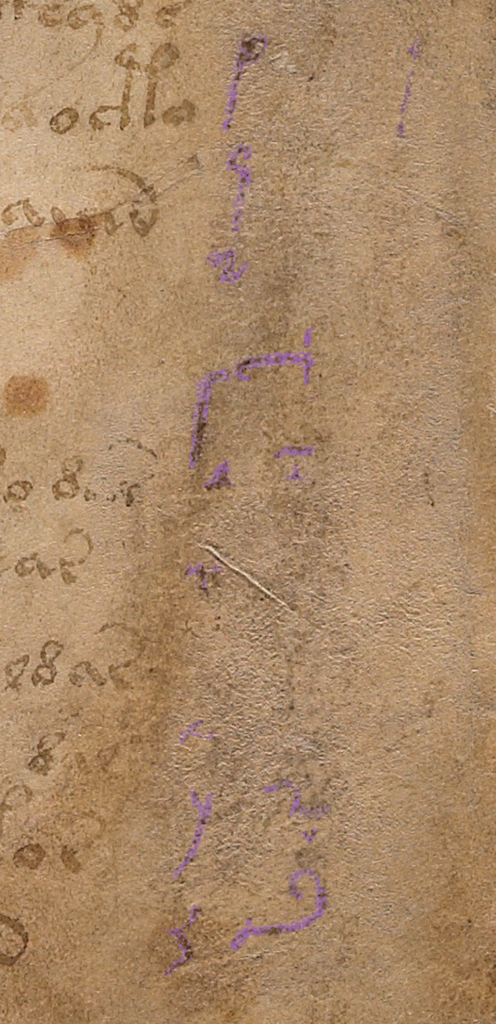

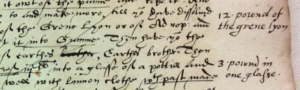

It has been said, as per expert opinion, that the VMS foliation is in Dee’s handwriting. I had to do a search, just now, to see who stated this, and found the name of A.G. Watson mentioned on the Voynich.nu site and thereafter found Kennedy and Churchill’s book, The Voynich Manuscript, in which I noted the following (courtesy of Google books):

“Most importantly, as Professor Watson wrote in 1986 to Yale University, ‘the foliation in the Voynich manuscript is Dee’s…even allowing for the notorious difficulty in deciding that figures are or are not in one hand, I am sure as I can be’. He refers to comparisons made with two Dee documents in the Bodleian Library’s Ashmole Collection…” (Kennedy & Churchill, 2006)

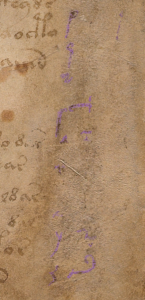

I am somewhat in sympathy with Professor Watson’s opinion, the handwriting is very similar to Dee’s handwriting, even given that Dee had three hands: a scrawly note hand, a script hand, and a calligraphic hand. Even though Dee’s handwriting is variable, there is still a reasonable amount of consistency in how he wrote numbers (with the calligraphic hand having slightly more serifs).

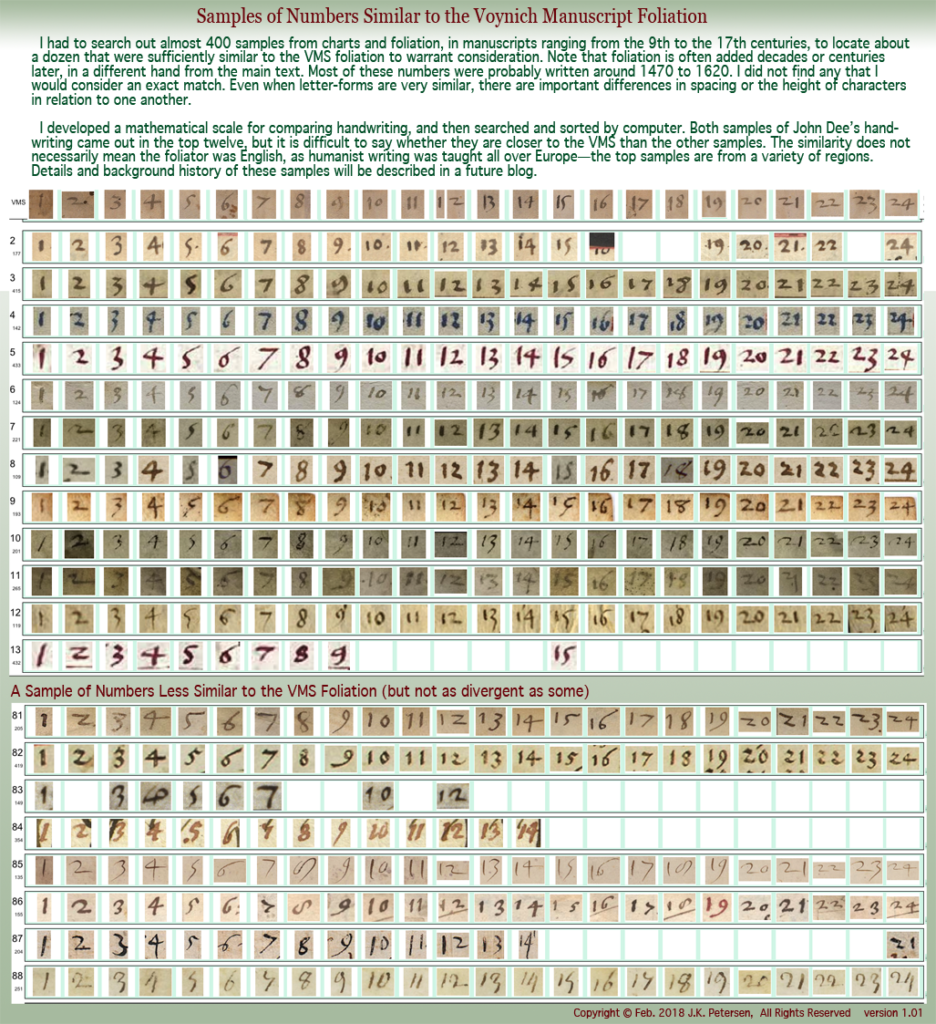

However, unlike Professor Watson, I cannot say that I am “sure as I can be” because I have found examples of numbers in other manuscripts, from other regions, that are arguably as similar or more similar to the VMS foliation than Dee’s.

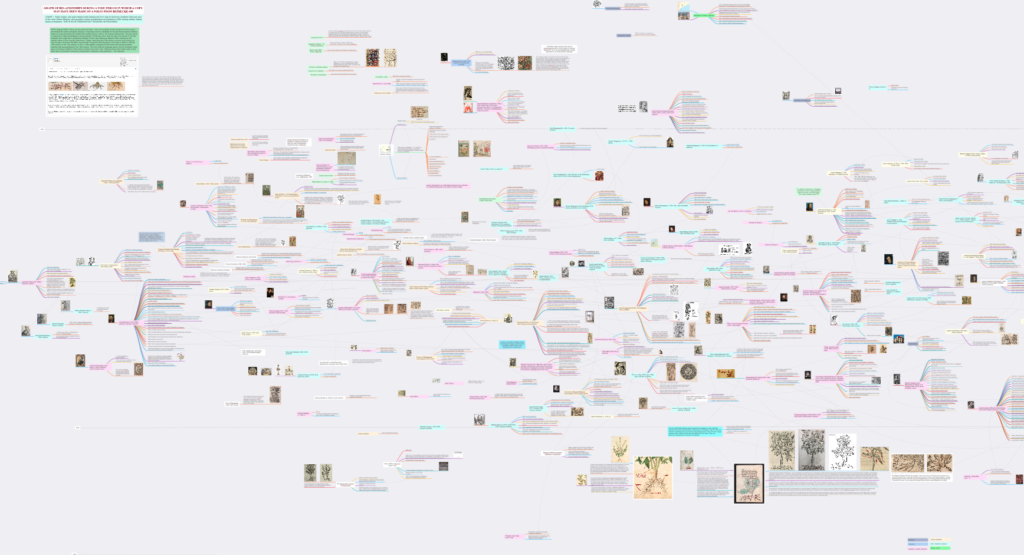

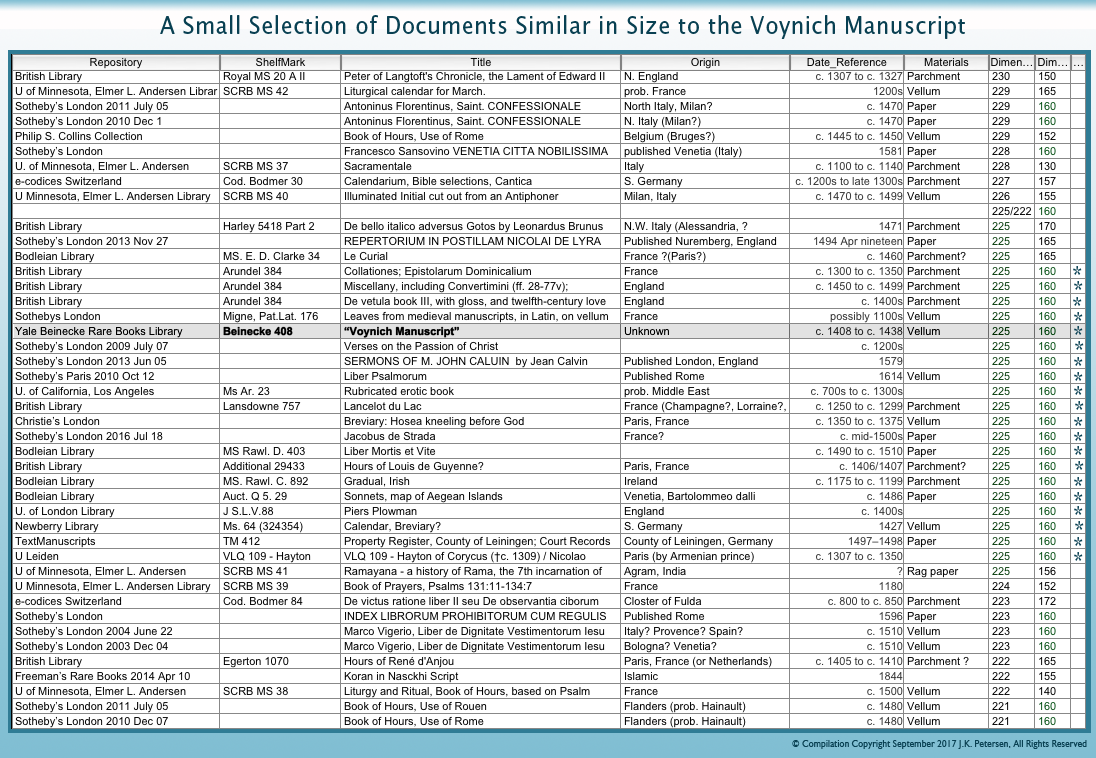

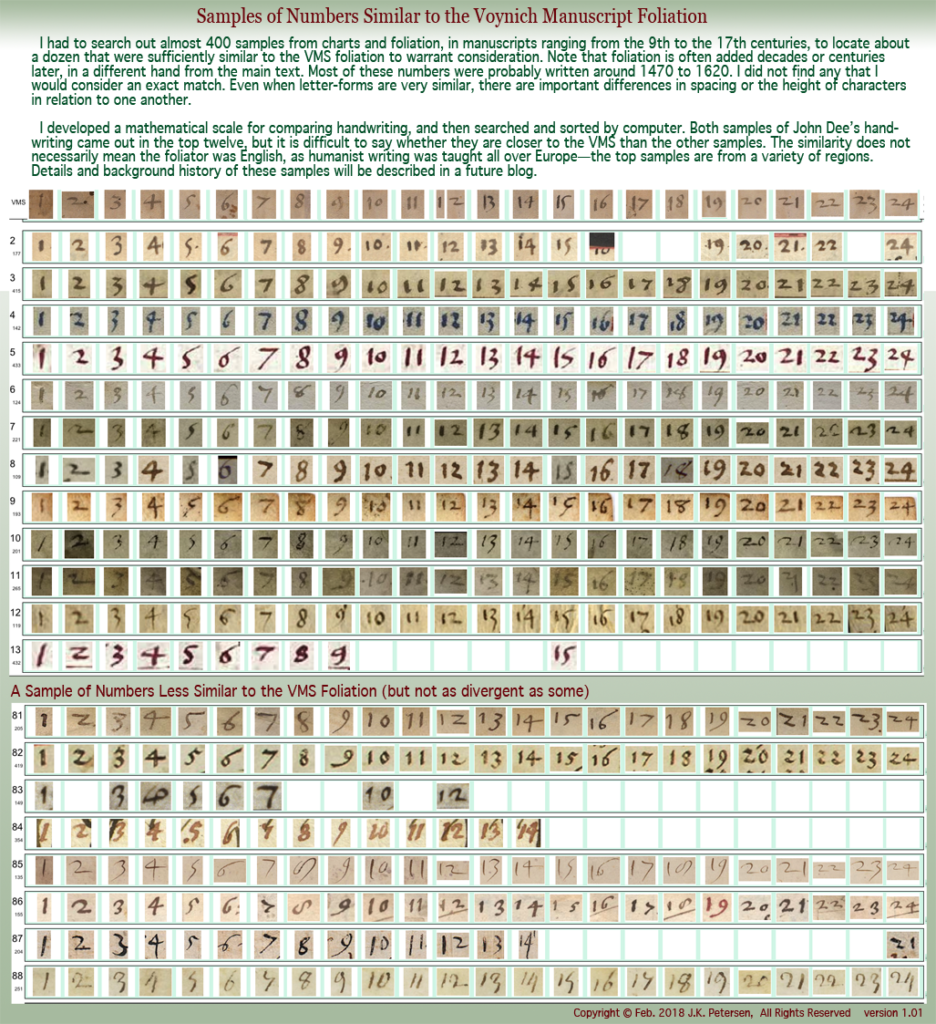

It wasn’t easy to come to this conclusion. I had to collect almost 400 samples of late Medieval and Renaissance numbers to locate about a dozen that were similar to the VMS foliation. In particular, the way the 3, 5, 7, and 9 are written in the VMS are specific to this scribe and difficult to find elsewhere as a group.

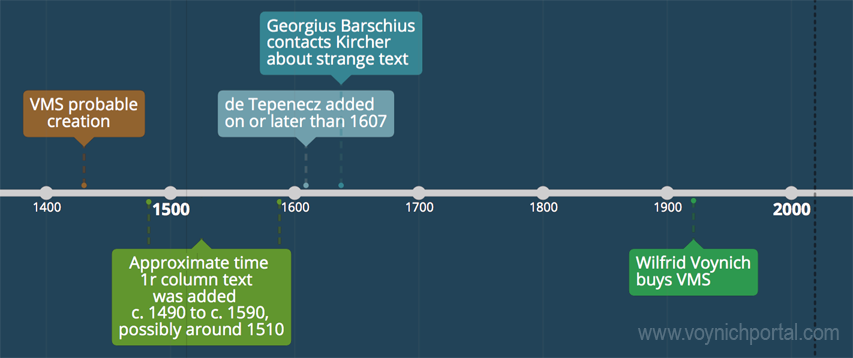

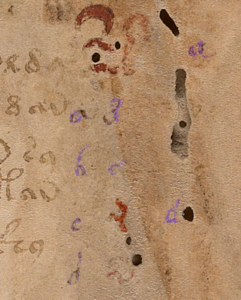

Note that the number system used for the foliation is of a later date than that of the quire numbers:

Comparing VMS Numbers to Those on Medieval Manuscripts

I consciously searched for samples that were similar to the VMS, and developed a mathematical scale for comparing the shapes more objectively so they could be searched and sorted by computer.

This is work-in-progress, but I am uploading a sample of what I have so far so the reader can decide whether the foliation can definitely be traced to John Dee (note that folio 12 is missing from the VMS, so the number has to be estimated by looking at others).

When sorted for the closest matches, two samples in Dee’s hand appeared in the top twelve. To convey a sense of how differently numbers could be written at the time, I have also included examples that scored in the middle, from 81 to 88.

I will discuss the results in more depth, with details about origin, date, and content, in a future blog. In the meantime, I’ll let you guess which ones are in John Dee’s handwriting (click to see full-sized):

From a total of nearly 400 samples gleaned from a variety of manuscripts dating from the 9th to 16th centuries, only about a dozen were significantly similar to the handwriting of the Voynich Manuscript folio numbers. Samples were taken from foliation and from number charts within the manuscripts themselves.

Summary

By itself, this chart does not disprove the possibility that the VMS was sold to Rudolf II by Dee and/or Kelley, but it does cast doubt on the assertion that it was John Dee who foliated the manuscript, as there are other hands that are similar and none appears to be a perfect match.

If Dee is eventually ruled out as foliator, then a Jesuit connection to the VMS, perhaps Jakub Horčický himself, might be more important to the manuscript’s provenance than previously thought.

J.K. Petersen

Copyright © 2018, J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved