The Lure of Mythical Creatures

We are fascinated by mysteries—the glimpse through a keyhole, a whisper behind the door, a rabbit pulled out of a hat, the Loch Ness monster, unicorns, fairies and the Voynich Manuscript.

Lady and the Unicorn tapestry. Courtesy of the Cluny Museum.

We also have a propensity for mutating our favorite myths into something more glamorous than their original models. Hence the cloven-hooved goat—the original unicorn—becomes a silvery horned horse and the horse, already a fleet animal, becomes even fleeter when it takes to the skies on Pegasus wings.

The Water Sprite Who Desired a Mortal Existence

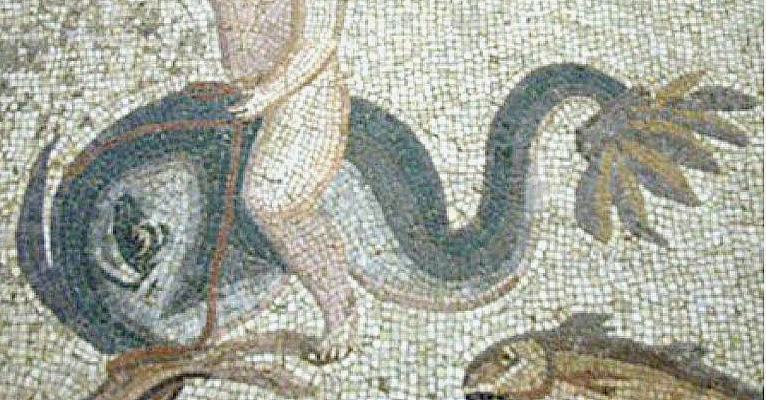

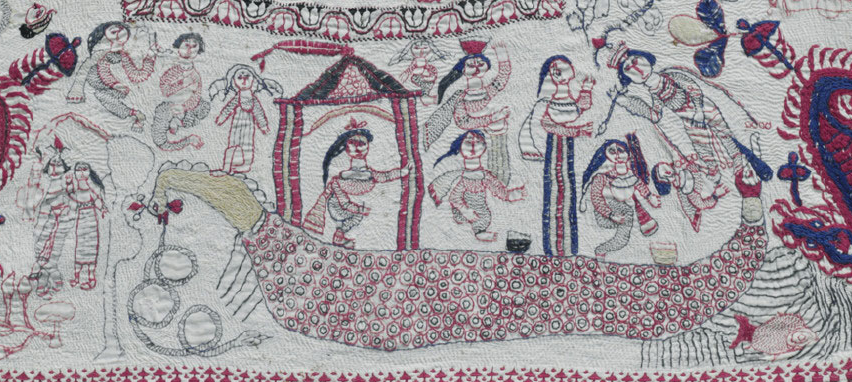

The legend of the melusine, a fairy with scaly legs, was passed down through oral history with certain monstrous characteristics not unlike those of the serpent in the Garden of Eden or the sirens of the seas, but also with qualities of beauty and sincerity and, in later retellings, of maternal devotion. Her union with a mortal resulted in children with defects, yet she and her husband loved them all.

The legendary half water-sprite, half mortal, was sometimes shown as serpent, sometimes as fish, but was usually distinguished from mermaids and sirens by being a fresh-water fairy or sprite, rather than a temptress of salt waters. Not always, however. It depends who is telling the story. In coastal locations, the melusine sometimes comes from the sea or, in others, Mélusina is a fresh-water sprite but her mother was a salt-water siren.

The legendary half water-sprite, half mortal, was sometimes shown as serpent, sometimes as fish, but was usually distinguished from mermaids and sirens by being a fresh-water fairy or sprite, rather than a temptress of salt waters. Not always, however. It depends who is telling the story. In coastal locations, the melusine sometimes comes from the sea or, in others, Mélusina is a fresh-water sprite but her mother was a salt-water siren.

In the story, Raymond is wandering disconsolate through the forest because he accidentally shot an arrow through his host while aiming at a boar and can’t go back because he will be charged with murder. Unexpectedly he hears a sweet singing voice and is enticed by a lovely sprite by a fountain and she, in turn, falls for Raymond, a mortal of noble blood. Unfortunately, his fate is insecure and his material prospects not too bright, so Mélusina helps him avoid the gallows and attain his desires, and gives herself to him on the stern promise that he never watch her on Saturdays, the day that she bathes. Raymond readily agrees.

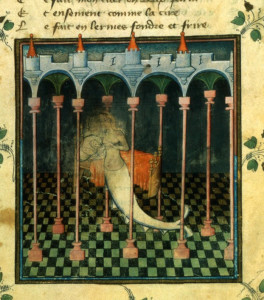

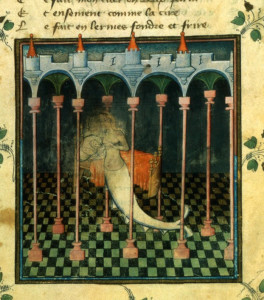

Mélusine and Raymondin in Marital Bliss

Bibliothèque Nationale de Luxembourg

At first, Mélusine’s husband honored his promise and they had a happy union. She furthered their fortunes by clearing land and building castles. But first Raymondin needed to acquire the land, so he asked for as much land as would fit on a hide. Laughing, a nobleman granted his wish—how much land can fit on a hide? But the clever Mélusine instructed Raymond to cut the hide into long fine traces that would stretch for miles and surround a good bit of property. Then she blessed him with numerous children.

Being a mixture of mortal and fairy blood, the children were robust but born with unsightly disfigurements. Nevertheless, their parents loved them dearly and the family grew large.

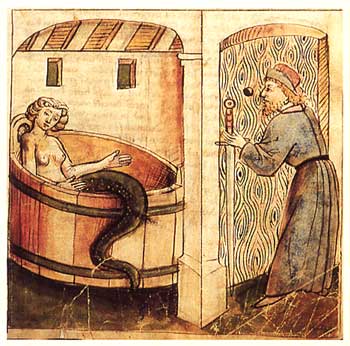

Mélusine in her bath. Book of Hours of Duc de Berry, 1392/1393.

Then a zealous (or perhaps jealous) brother put a bug in Raymond’s ear to erode his faith in his wife and convinced him to find out what she was doing behind his back. So Raymond spied on her during her bath and discovered she had the legs of a serpent.

Mélusina cried out in anguish at his betrayal and he swooned when he realized she had done no wrong and that his actions had doomed her to spend eternity in an uneasy spirit world.

In some versions, she disappears into netherlife with the children, in others, she stays but the children spiral downward into unspeakable acts and Raymond blames her because she is an unnatural creature. Either way, the trust is broken and the relationship irrevocably destroyed.

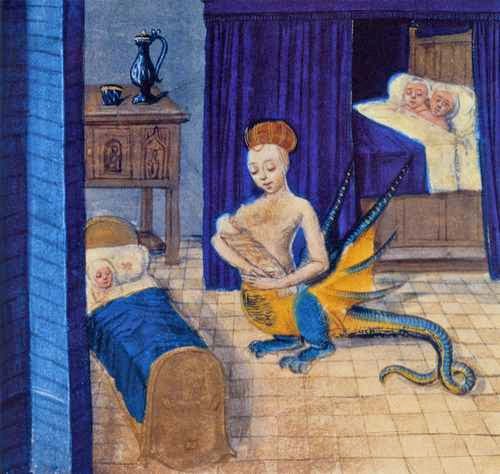

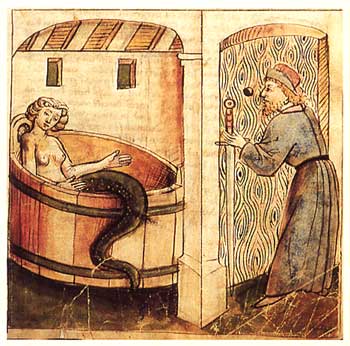

Mélusina with her numerous children from Historia de Melusina, by Couldrette, París, 1401, Courtesy of Biblioteca Nationale de Francaise..

Written Versions. The legend of the melusine, passed down through oral history, was popularized in Roman de Mélusina, written for Jean, duc de Berry and Guillaume l’Archèvesque by Jean d’Arras in 1392/93. In 1401, it was retold in verse by Couldrette, with Mélusine depicted not only with a serpentine lower body, but also bird legs and wings.

The story spread through textual and illustrated manuscripts across Lombardy through the 14th and 15th centuries. A “mermaid” illustrated on land, keeping company with her children or being spied upon in a bath isn’t a mermaid at all, it’s a melusine, a water sprite. Mélusine is sometimes shown combing her hair in the bath when she is discovered by her husband, but she is not typically shown with a mirror.

Mermaid, Melusine or other Mythical Creature?

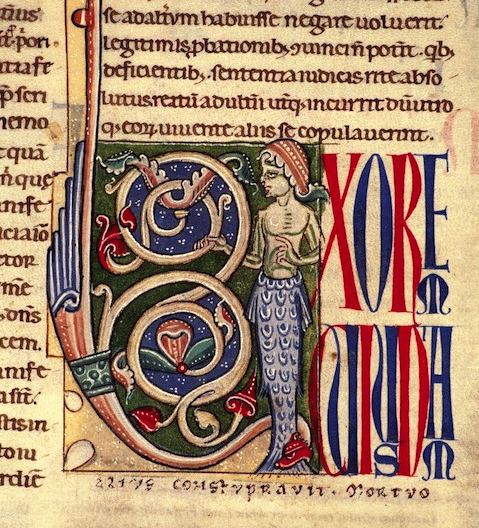

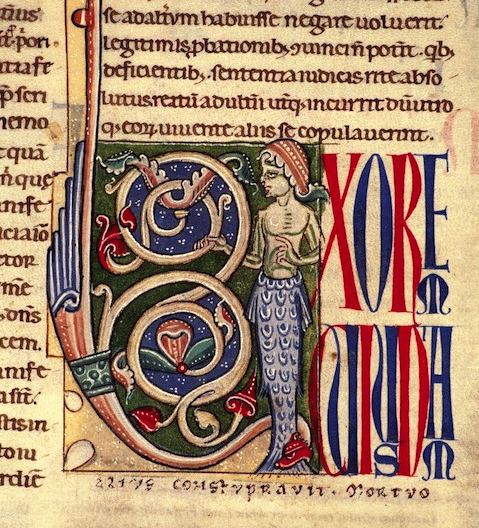

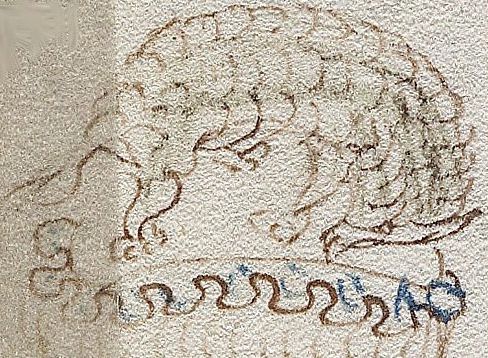

In the Hunterian Psalter, an ecclesiastical manuscript of the early 12th century, “Psalm 89” has been illuminated with an initial of a long-haired man or woman with a comb, climbing out from a scaly tail. There’s not enough context to know if it’s a reference to the legend of Mélusine—a story of faith, trust, and betrayal—or to something else. There are a couple of mentions of the sea and other water in the verse, but they are not central to the words of Ethan, the Ezrahite, who rebukes God for making and breaking a promise and cries out, “Lord, where is your former great love, which in your faithfulness you swore to David?”

In the Hunterian Psalter, an ecclesiastical manuscript of the early 12th century, “Psalm 89” has been illuminated with an initial of a long-haired man or woman with a comb, climbing out from a scaly tail. There’s not enough context to know if it’s a reference to the legend of Mélusine—a story of faith, trust, and betrayal—or to something else. There are a couple of mentions of the sea and other water in the verse, but they are not central to the words of Ethan, the Ezrahite, who rebukes God for making and breaking a promise and cries out, “Lord, where is your former great love, which in your faithfulness you swore to David?”

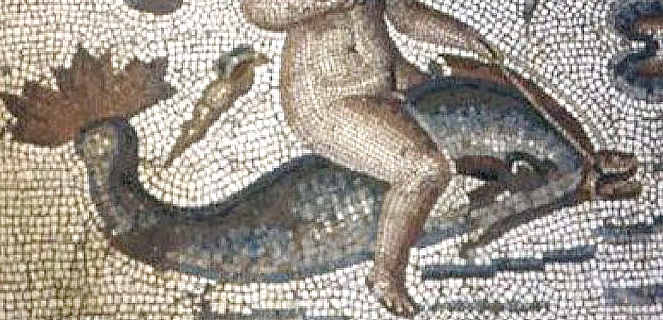

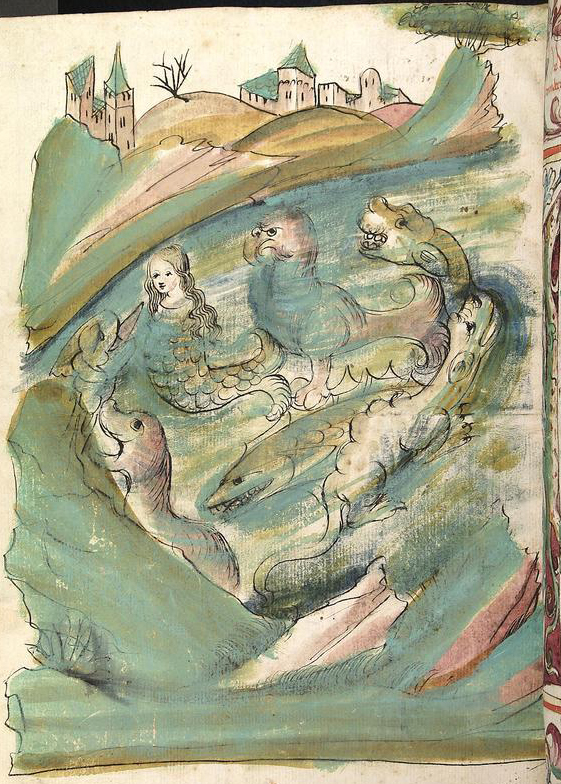

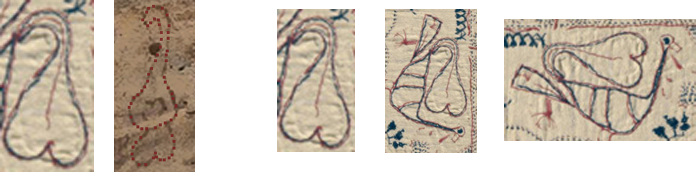

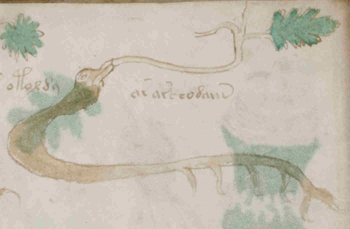

There is also a mermaid-like creature in the Voynich Manuscript, at the bottom of Folio 79v—half-woman, half-fish, immersed in a pool of green water. Except, like the embellished initial, it’s not one creature but two—a woman with regular legs and what looks like a spotted fish with two eyes and an unusual mouth. You almost expect to see a zipper. The mouth looks more like a costume than a natural fish, especially if you consider the rest of the fish looks more natural than many drawings of mermaid tails. I wondered sometimes if this were a variation of the Noah’s arc tale, but somehow it doesn’t feel that way to me.

There is also a mermaid-like creature in the Voynich Manuscript, at the bottom of Folio 79v—half-woman, half-fish, immersed in a pool of green water. Except, like the embellished initial, it’s not one creature but two—a woman with regular legs and what looks like a spotted fish with two eyes and an unusual mouth. You almost expect to see a zipper. The mouth looks more like a costume than a natural fish, especially if you consider the rest of the fish looks more natural than many drawings of mermaid tails. I wondered sometimes if this were a variation of the Noah’s arc tale, but somehow it doesn’t feel that way to me.

Without the text, it’s difficult to explain this creature or the tube-like drawings up along the left side, or the other critters on the right side of the pool but I believe there are some important clues on this page and that the fish-woman may relate to the tale of the melusine, either directly or indirectly.

Similar Story and Illustrative Traditions

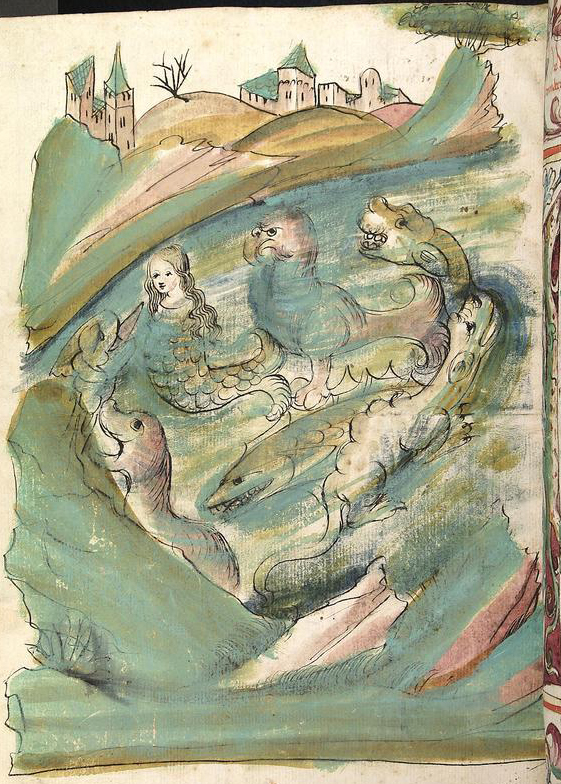

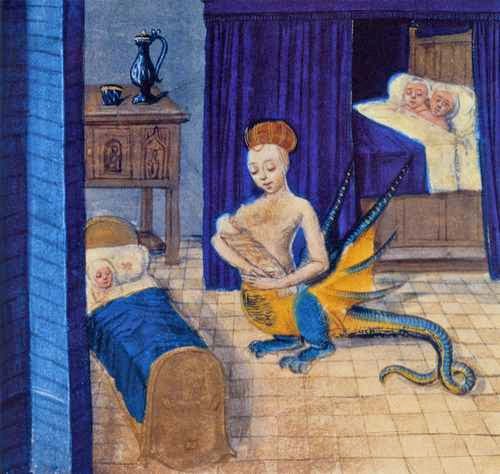

Das Buch der Natur, Lauber Workshop, Hagenau, Alsace, c.1440s

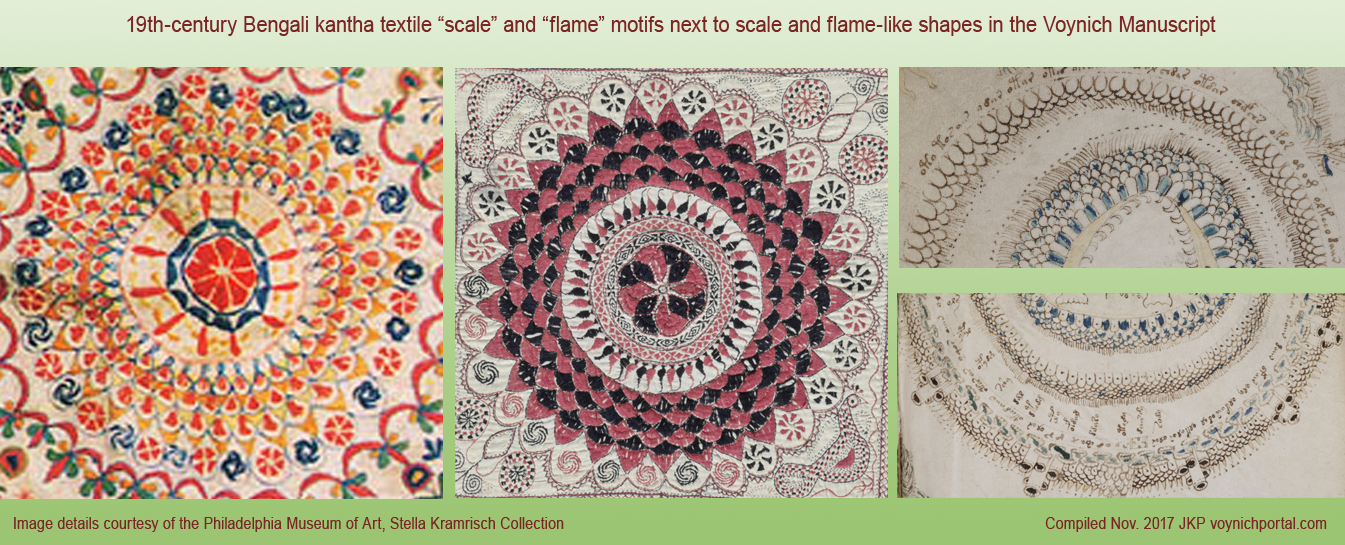

A few years ago, I began tracing the script styles on the last page of the VMS and discovered some illustrations, accompanied by Gothic Cursive text, that were hauntingly similar to the “mermaid” page in the VMS.

Even though the mer-creatures aren’t the same as the VMS woman-in-fish creature, the way the animals were drawn and the pigments used, have many commonalities. I’m fairly certain it’s not the same artist—the water is always drawn differently, as is the fish-like creature in the VMS version, and the parchment of the commercial document appears smoother than the VMS—but otherwise, except for the obvious difference in drawing skills, they are so similar, it’s tempting to wonder if the two illustrators might be related in some way or if the VMS illustrator were somehow connected to the workshop by friendship or by blood.

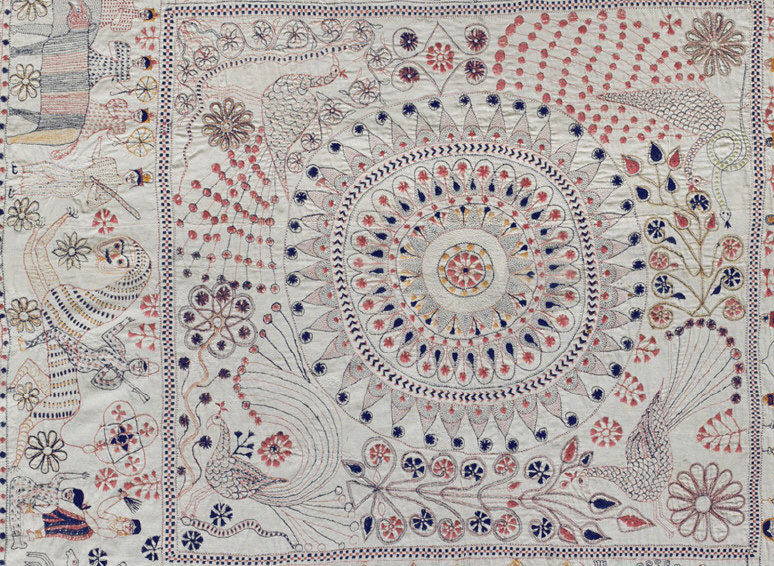

First notice the pigments—simple greens, blues, bluffs, and browns, quite subdued compared to Spanish and French illuminations of the time that included vibrant blues, greens, and golds.

First notice the pigments—simple greens, blues, bluffs, and browns, quite subdued compared to Spanish and French illuminations of the time that included vibrant blues, greens, and golds.

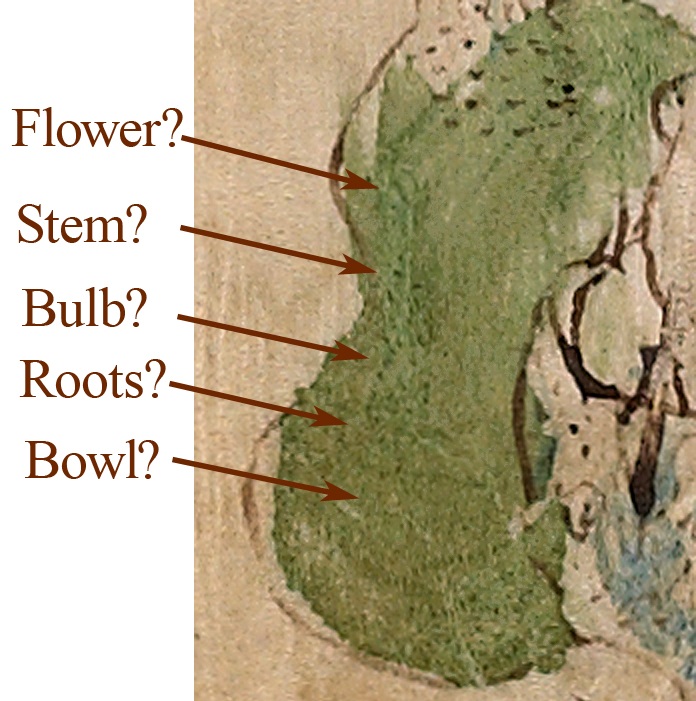

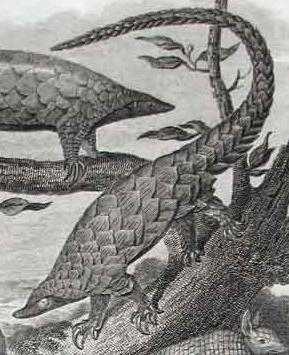

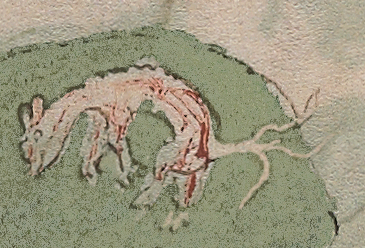

In addition to the limited palette, note the indistinct way the animals are drawn—you can’t quite tell what they are. This is also true of the critters on Folio 79v. They are not quite a dog, a lion, or a fox and the creature below the fish tail doesn’t quite resemble a lizard or salamander, either, not with that kinky tail.

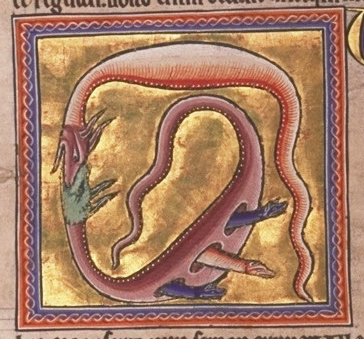

Now, if you inspect the illustration of the “melusine” from Das Buch der Natur (note the serpent’s tail rather than a fish tail) and look closely at that little creature caught up in the tail on the top right you might note its resemblance to one of the VMS critters. Also note these details:

Now, if you inspect the illustration of the “melusine” from Das Buch der Natur (note the serpent’s tail rather than a fish tail) and look closely at that little creature caught up in the tail on the top right you might note its resemblance to one of the VMS critters. Also note these details:

- the little animal has a happy face,

- the tail belongs to the melusine, not the little animal, and

- the VMS critter (which I have rotated to make it easier to see the similarities), has the tail originally drawn, but then painted over.

This painted-over tail is likely a coincidence (rather than a sign that the VMS illustrator may have copied and corrected the little critter) as Das Buch der Natur probably post-dates the VMS by as much as 20 or 30 years, but is it possible that both the VMS and Das Buch der Natur were taken from a common source? The workshop that created Buch der Natur is thought to descend from a similar workshop that operated in the early 15th century (one with a more formal and traditional illumination and script style but in the same region).

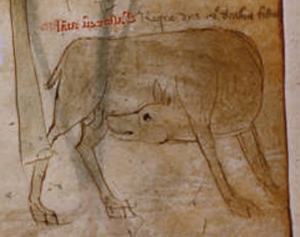

Also, note an even more important detail that I mentioned in my 2013 post on the zodiac symbols—the VMS illustrator had difficulty drawing hind legs.

Also, note an even more important detail that I mentioned in my 2013 post on the zodiac symbols—the VMS illustrator had difficulty drawing hind legs.

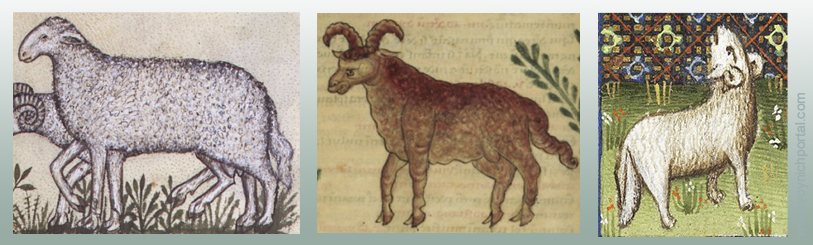

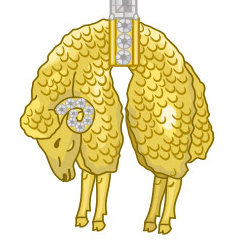

Look again at Taurus and Aries. The illustrator doesn’t quite get that the “elbows” of the hind joints point backward rather than straight down or forward, an anatomical detail that is usually drawn correctly in medieval manuscripts and which is semi-flubbed in the VMS.

In Das Buch der Natur, we find this same quirk! In both drawings, the hind quarters are indistinct and ambiguously drawn—the illustrators apparently can’t envision the inner structure of the bones and joints even though the other parts aren’t drawn too badly. In fact the illustrator on the right drew a pretty good face.

Summing Up

So what does all this mean?

Pigment and writing traditions can sometimes help identify a place of origin as can the way parchment is obtained and prepared. The palette and writing style on the last page closely match those of Das Buch der Natur. The VMS main text doesn’t match anything that can be specifically identified and we don’t know if the person who did the drawings and the person who added the text are the same.

It’s not certain whether the woman in the fish (if it is a fish) is separate from the fish or allegorically related to the fish, but the drawing could be derived from one of the popular legends at the time, especially considering there are other critters on the same page that evoke the same “feel” as the critters in Das Buch der Natur.

It’s not certain whether the woman in the fish (if it is a fish) is separate from the fish or allegorically related to the fish, but the drawing could be derived from one of the popular legends at the time, especially considering there are other critters on the same page that evoke the same “feel” as the critters in Das Buch der Natur.

Maybe the woman on Folio 79v is a melusine donning her fishtail during her Saturday bath, or maybe there’s no connection to mythical creatures at all. I think we can say, however, that it’s probably not a mermaid, since the fish and woman appear to be separate creatures, and there’s no sign of a mirror as seen in most pictures of mermaids.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2016 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

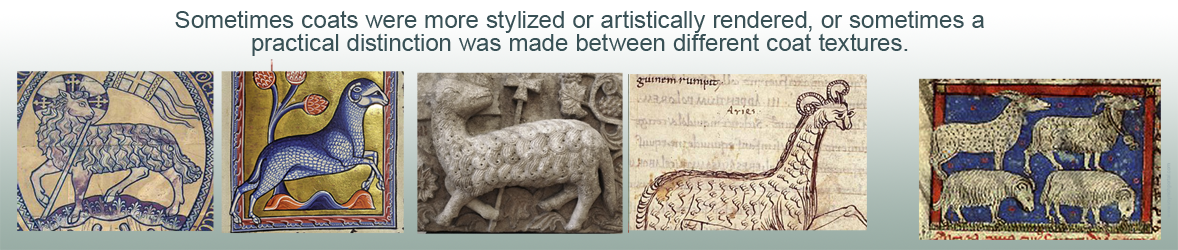

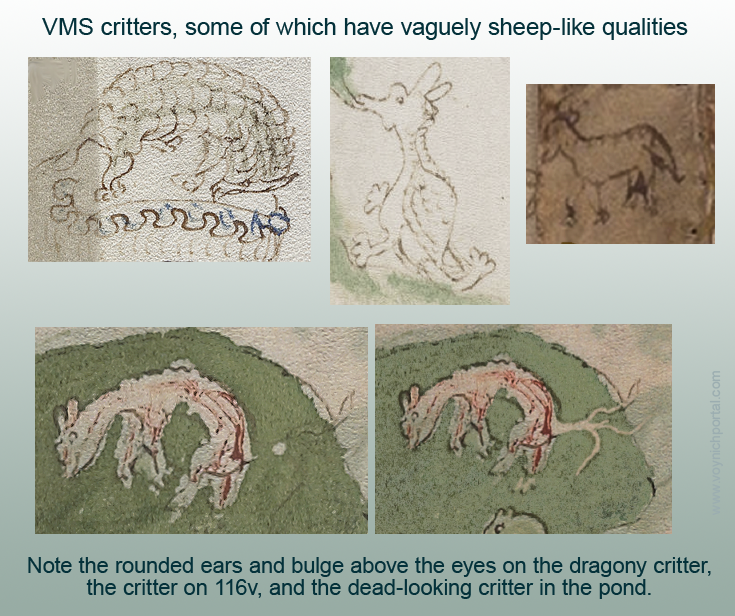

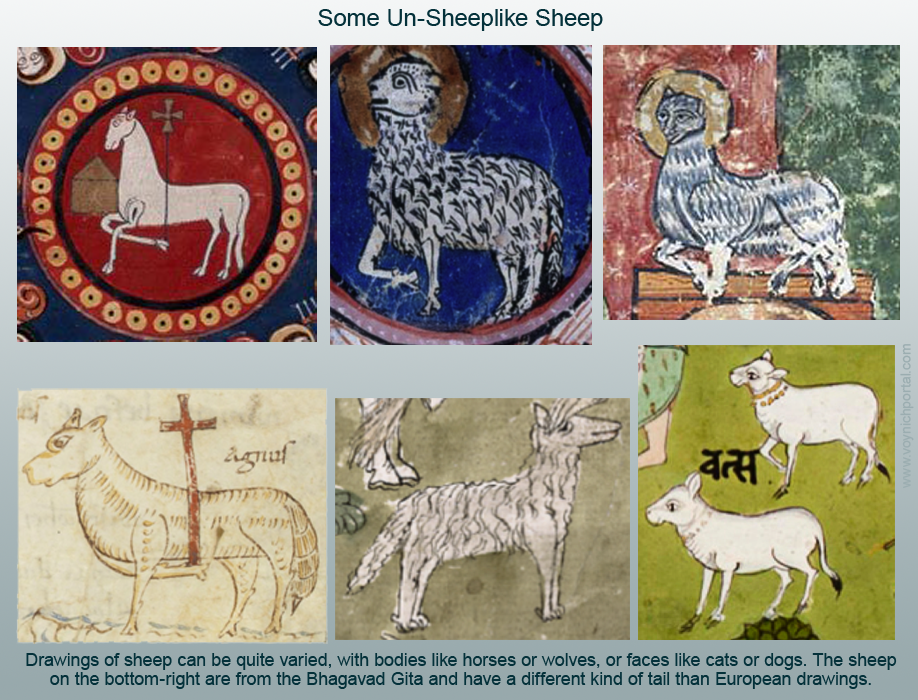

The most common way to draw the sheep bodies was with lines following the direction of the coat, especially tufts:

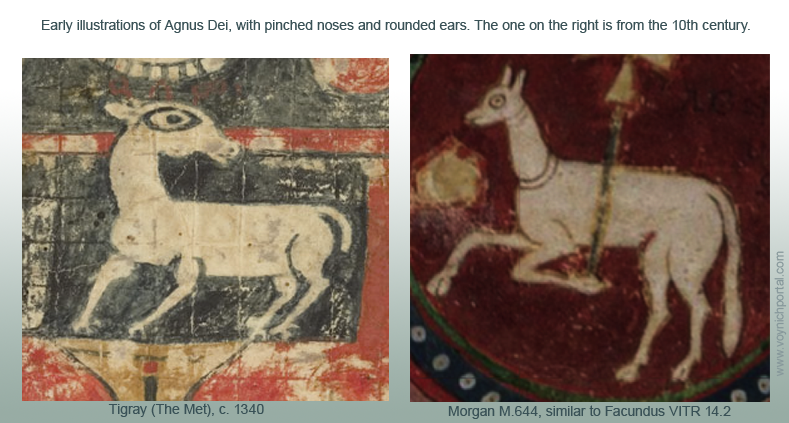

The most common way to draw the sheep bodies was with lines following the direction of the coat, especially tufts: In terms of drawing style, there were two very early drawings that caught my eye. They have the pinched nose and pointy rounded ears one sees on the VMS dragony critter and dead-looking pond critter. This doesn’t necessarily mean a connection, but I found them interesting nonetheless. Note that the one on the right, which illustrates the lamb of God, has a body that looks more like a horse than a sheep and the one on the left also has a rather long neck for a sheep (even one that is recently shorn):

In terms of drawing style, there were two very early drawings that caught my eye. They have the pinched nose and pointy rounded ears one sees on the VMS dragony critter and dead-looking pond critter. This doesn’t necessarily mean a connection, but I found them interesting nonetheless. Note that the one on the right, which illustrates the lamb of God, has a body that looks more like a horse than a sheep and the one on the left also has a rather long neck for a sheep (even one that is recently shorn): The VMS drawings sometimes have more in common with drawings of the early and middle medieval periods than the late 15th century. This might indicate access to a library that included early manuscripts, or it might be a consequence of limited drawing skills. Note that the sheep on the left has paws, just as the VMS zodiac hooves are somewhat rounded and paw-like.

The VMS drawings sometimes have more in common with drawings of the early and middle medieval periods than the late 15th century. This might indicate access to a library that included early manuscripts, or it might be a consequence of limited drawing skills. Note that the sheep on the left has paws, just as the VMS zodiac hooves are somewhat rounded and paw-like.

It’s not unusual to find a feathered tail on images of animals that look like lions, but the critter top-right has a very strange branch-like (or root-like) appendage where one would expect a tail and the lower-left one is unusual too.

It’s not unusual to find a feathered tail on images of animals that look like lions, but the critter top-right has a very strange branch-like (or root-like) appendage where one would expect a tail and the lower-left one is unusual too.