7 May 2019

You may remember an announcement by Gerard Cheshire that he had found a proto-Italic solution for the VMS. There was no corroboration for his theory by any of the scholars who are well-acquainted with the text and, to date, I haven’t seen Cheshire provide an objective verifiable solution.

He has now completed his Ph.D. and is making a bold and possibly proposterous claim that he solved the Voynich Manuscript shortly after discovering it and that his so-called solution “was developed over a 2-week period in May 2017” [Tandfonline.com 2019 Apr 29].

Who would claim to solve the VMS and then post a series of papers (Jan. to Apr. 2018) based on a few isolated sections that do not provide a convincing solution? Proposing that it is an extinct language is no more valid than any other VMS theory.

Since I am not willing to pay $43 (or even $4) to download the current version of his paper, I will restrict my remarks to the last of the previous papers, dated April 2018, which I only just read for the first time today (the link to Cheshire’s paper redirects from The Bronx High School of Science student newspaper’s site to sites.google.com).

Cheshire’s “Linguistic Dating” Theory

In the introductory section Cheshire states, “…in this regard, manuscript MS408 is ‘manna from heaven’ to the linguistic community, as it offers the components necessary to compile a lexicon of proto-Romance words, thanks to the accompanying visual information.”

He then claims that his “proto-Italic alphabet is shown to be correct, so we know that the spelling of the words is also correct, even if unknown”, and then goes on to say that pages without illustrations “will, of course, be more of a challenge…”

Besides the dubious claim that the “proto-Italic alphabet is shown to be correct…”, I’d like to point out that most VMS folios include illustrations. If you can decipher 200 pages with help from illustrations, then the ones without shouldn’t be too difficult, considering that Voynichese is reasonably consistent from beginning to end.

Cheshire then claims labels are easier to interpret (personally I haven’t seen anyone translate the labels in any verifiable way, but let’s continue):

“The longer sentences are filled with conversational connectives, pronoun variants, singular-plural terms, gender specifics and so on, that make it necessary to identify the unambiguous marker words and then make sense of the equivocal words by a process of sequential logic.”

This stopped me in my tracks. One of the characteristics of the Voynichese that truly stands out is the similarity and repetitiveness of beginnings and endings. How can one identify singulars, plurals and gender specifics in text where the beginnings and ends appear to be stripped of their diversity? I guessed that Cheshire must be either shuffling spaces or breaking up tokens (or both).

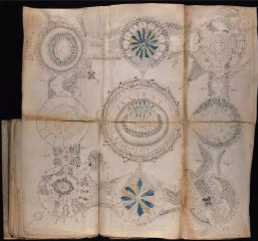

The 9-Rotum Foldout as Example

To demonstrate his claim that the VMS uses a proto-Romance language and proto-Italic alphabet, Cheshire presents a partial analysis of the 9-rotum foldout folio, which he refers to as the Tabula regio novem.

He claims the correlations, “…are beyond reasonable doubt in scientific terms. Most of the annotations are translated and transliterated with entire accuracy…”

Another bold claim that doesn’t live up, in my opinion. But let’s look at his analysis…

Cheshire identifies Rotum7 as a volcanic eruption. I think this is possible, based on visual similarity alone, and others have suggested this possibility. However, it could just as easily be an image of mountain springs (the source of water) or a river delta as it spreads out in an alluvial fan or… something else.

So how does Cheshire support his claim?

Rotum7 Translation

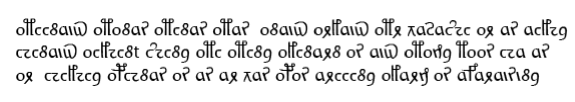

Cheshire transliterates the text around the circumference as follows [I’ve added a Voynichese transcript to make it easier for readers to compare them and to see how Cheshire has broken up VMS tokens to create “words”]:

om é naus o’monas o’menas omas o’naus orlaus omr vasaæe or as a ele/elle a inaus o ele e na æina olina omina olinar n os aus omo na moos é ep as or e ele a opénas os as ar vas opas a réina ol ar sa os aquar aisu na

Note that EVA-ot is alternately translated as part of a word or as a separate letter with apostrophe to separate it from the following chunk. The breaking of words in various ways is, of course, subjective interpretation, and would have to be verified by testing the more common divisions on larger chunks of text.

Cheshire translates the above passage as follows:

people and ship in unity take charge mothers/babies of ship to protect life-force pots [he says this is pregnant bellies] yet in he/she at inauspicious/unfavourable he/she is in a/one omen to look it is man not mouse epousee and embrace an opening thus you go but carefully to the queen to facilitate not getting wet with seawater

So before we look into the details of the translation, this supposed narrative seems to me to relate more to river basins and seaports than it does to volcanoes. Cheshire’s contention that this text helps pinpoint the location and time period of the VMS’s creation via a volcanic eruption can definitely be challenged.

But let’s look at the interpretation. Here are some observations:

- Cheshire has chosen a rare character to represent f/ph, and u/v. Less than 50 instances of one of the most common letters in Latin and Italian in c. 38,000 words of text is hard to believe. In classical Latin versions of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the u/v character would occur about 15,000 times in 38,000 words (that’s not even including the f).

- There’s no word “inaus” in Latin, Italian, French, or Spanish (in fact, it’s more Germanic than Romance), so Cheshire has expanded it to mean inauspicious via Latin inauspicatus. Presumably he feels it’s acceptable to subjectively choose which tokens might be truncated.

- Obviously Cheshire is using variations of “om” to mean homo/people, thus om (people) omas (mothers/babies), omo (man), but he chose to interpret “omenas” as o’menas (take charge) rather than as om enas (people swim). People swimming is arguably more consistent with the surrounding subject matter. This illustrates that his interpretation has a strong element of choice. I’m not even sure why o’menas would mean “take charge”.

- Some of the translation seems rather nonsensical and hard to relate to volcanoes, such as “to look it is man not mouse and marry and embrace an opening thus you go carefully to the queen to avoid not getting wet with seawater”. Consider that “aisu” is neither Italian nor Latin and the grammar is seriously questionable.

- I’m not sure why Cheshire seguéd to Persian for “moos” (mouse). Moos is an acceptable alternate spelling for “mus” in western languages. Perhaps it was to justify his choice of Persian to explain another word “omr” which has no equivalents in Romance languages. Going to non-Romance languages when a word doesn’t fit his theoretical framework introduces yet another level of subjective interpretation.

- The choice of phrase-breaks is clearly also subjective. Cheshire separated “opénas” from “os” even though they go together better than combining “os” with the following phrase. The word “opénas” itself is questionable—it’s not likely to be expressed this way and it could be interpreted quite differently as a penalty, punishment, or even as sympathy.

Overall, there is only a vague coherence to it, one that does not evoke thoughts of volcanoes, and one that makes little grammatical sense.

In his summation of the text, Cheshire does not explain why text unrelated to volcanoes would confirm that the Rotum7 IS a volcano and avoids any explanation of why marriage and the queen would be included.

Confirmation Bias?

In the next section Cheshire identifies the symbol bottom-left as a compass (I personally think it looks more like a sextant, which was used for surveying as well as navigation, but I’m not sure what it represents). His transliteration is “op a æequ ena tas o’naus os o n as aus[pex]”, which he translates to “necessary to equal water balance of ship as it is propitious”.

A compass doesn’t really have anything to do with a ship’s water balance (and doesn’t relate to volcanoes either) and I would like to know why he says “op” means “necessary” when the root “neces-” is common to all major Romance languages. In Romance languages “op” is more likely to equate to “work/produce” than to “necessary”, and once again the grammar is abnormal.

From these two pieces of “translation”, Cheshire takes a logical leap that only two volcanoes might be plausible for Rotum7: Stromboli and Vulcano and states:

“…Vulcano is known to have erupted very violently in the year 1444, which corresponds with the carbon-dating of the manuscript velum: 1404-1438.”

He further translates the Rotum7 inner annotations as “of rock, both directions, not so hot, veers here, it twists, reducing, it slows, middling/forming, of rock it is”.

This could describe mountain springs (the source of water) just as easily as a volcanic eruption. I’m not denying that Rotum7 might be volcanic flow, it’s on my list of possibilities, only that Cheshire’s argument is not as definitive or scientific as he claims. Also, I would like an explanation of how he turned “oqunas asa” into “both directions”.

Origins of Glyph Shapes

Cheshire has this to say about VMS glyph shapes:

“…the symbol is an inverted v with a bar above. It seems to derive from the Greek letter Pi in lowercase (π),…”

I disagree. Pi was rarely written like EVA-x in medieval manuscripts. However, alpha and lambda are sometimes written this way, including Greek, Coptic, and old Russian scripts (I have collected many samples). I think it’s unlikely that EVA-x is based on the shape of Pi.

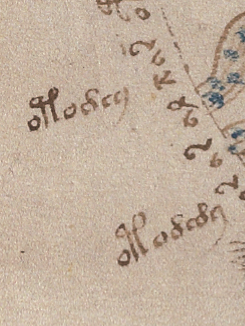

Rotum7 Side Labels

I can’t go through every translation point-by-point, but if you are reading along, on page 7 of his paper, you’ll notice Cheshire inserted the word “lava” many times when it wasn’t part of the translation. I don’t know if he was trying to convince us or himself.

Note that in two places, he translated “omon” (EVA-otod) as lava. Now take a look at this:

Cheshire translates EVA-otodey as omon ena and EVA-otody as omon ea. In his system, this translates to “lava largest” and “lava smaller”. If this system were applied consistently throughout the manuscript then we are looking at root-suffix constructions, with EVA-ey as largest and EVA-edy as smaller. This has significant implications for interpretation of the rest of the text but Cheshire didn’t address this.

If you’ve been paying attention to the translations, you might have noticed certain inconsistencies. Cheshire presents omo as people/humans and omon as lava, and now omona as “big man” (it’s not hard to follow the logic) but does not explain why these words would occur in other places in the manuscript where the context does not seem relevant. He also inserts increasing levels of subjective interpretation to explain the “story” behind the rosettes folio and asserts that Rotum8 depicts emergency refuge from the eruption and Rotum 9 is emergency relief in the form of free bread on tables.

Summary

As for the letters “o” that occur so frequently at the beginnings of words, Cheshire variously interprets them as conjunctions and articles. I’m not going to argue with this because I think it’s possible the over-abundant leading-“o” glyphs could have a special function as markers or grammatical entitites, but even with this flexibility, Cheshire’s grammar falls apart upon inspection. Even notes and labels usually exhibit certain patterns of consistency, that are not readily apparent in the translation.

I’m also not going to argue with the choice of location for these volcanoes (if they are volcanoes), because I’ve considered the Naples area many times, have blogged about it, and it’s still on my list of favored locations.

But I have trouble accepting the translation in its current form because

- there are a lot of nonsensical word combinations,

- there’s almost no grammar,

- the letter distribution is quite different from Romance languages (it would take a whole blog to discuss this aspect of the text, but take 4 as an example, which almost exclusively is at the beginnings of tokens—Cheshire relates it to “d”, and “9” which is usually at the end and sometimes at the beginning, but almost never in the middle, which he designates as “a”),

- the words still match the drawings if the drawings are interpreted differently (which means the relationship isn’t proven yet),

- some of the transliterated “words” don’t show any relationship to Romance word-structures (and the author neglected to explain how specific non-Romance words were derived), and

- the same words (e.g., “na”) are sometimes interpreted differently.

If Rotum7 turns out to be flows of water, rather than flows of lava, Cheshire’s arguments about time period and location are seriously weakened. Even if it turns out to be lava, the problems with the translation have to be addressed, because it seems more relevant to water than it does to lava.

Consider also that Cheshire’s word “naus” (EVA-daiin) is translated as nautical vessels, but the author doesn’t explain why this exceedingly common Voynich chunk, that is usually at the ends of tokens, would occur in almost every line, and sometimes more than once per line, throughout the manuscript.

Cheshire hasn’t given a satisfactory explanation of why a mid-15th-century scribe would use an undocumented proto-Italian script from c. 700 C.E. or earlier.

And let’s be honest, the translations are semantically peculiar. The human mind is designed to construct meaning from small clues, to fill in the gaps, so it’s easy to read meaning into almost any collection of semi-related words, but it’s very difficult to confirm anything that doesn’t quite hold together in normal ways.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2019 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved