Description

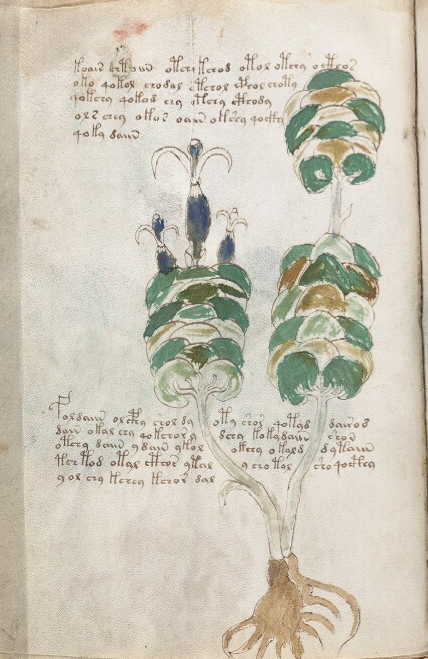

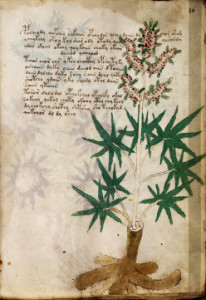

There is a large plant drawing occupying most of Folio 16r, accompanied by three blocks of text (if you consider the hanging indent as part of the first “paragraph” and the text at the top right a continuation of lines 1 and 2). The plant has some very specific and fairly naturalistic characteristics.

There is a large plant drawing occupying most of Folio 16r, accompanied by three blocks of text (if you consider the hanging indent as part of the first “paragraph” and the text at the top right a continuation of lines 1 and 2). The plant has some very specific and fairly naturalistic characteristics.

The root is thick, appears to have short root hairs, and is painted brown. The stems grow out from a bole (a diagrammatic representation of a tough woody base), something you might find on a sturdy shrub or tree.

The star-like serrated leaves have from seven to nine leaflets and are somewhat widely spaced along the main stem. The leaves are attached by fairly long stems and are peltate (centered) or nearly so.

At the top of the plant are what appear to be fruiting bodies or very small florets, with leaflets poking out from between them that are rounder than the lower leaves, singular, and painted a slightly lighter shade of green.

Identification

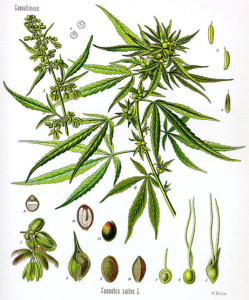

I didn’t bother to seek out identifications of this plant by other Voynich researchers because it looks so much like Cannabis it’s hard to imagine it as anything else. Cannabis plants can grow quite large and treelike, sometimes over nine feet high. They have distinctive buds at the ends of the stems, with leaflets visible between the numerous florets. The leaflets aren’t quite as blunt as FM 16r, but the lower leaves do tend to be a bit darker. As the fruiting bodies mature, the area around them darkens to a reddish brown.

I didn’t bother to seek out identifications of this plant by other Voynich researchers because it looks so much like Cannabis it’s hard to imagine it as anything else. Cannabis plants can grow quite large and treelike, sometimes over nine feet high. They have distinctive buds at the ends of the stems, with leaflets visible between the numerous florets. The leaflets aren’t quite as blunt as FM 16r, but the lower leaves do tend to be a bit darker. As the fruiting bodies mature, the area around them darkens to a reddish brown.

Small Cannabis plants have numerous fine roots and I wasn’t able to verify whether large plants develop the heavy roots illustrated in Plant 16r. If not, then either this is a different plant or the VM illustrator was guessing (or ascribing some unknown meaning to the shape of the roots).

Other Possibilities

No matter how much 16r looks like Cannabis, it’s important to consider alternatives.

Lupinus plants have star-like leaves, but the flower spikes differ markedly from Plant 16r. There are other plants with leaflets poking out from the florets, but their leaves differ significantly from Cannabis.

One could frame an argument that this is a chaste tree (Vitex agnus-castus), another ancient medicinal herb, but chaste-tree branches split and spread more broadly than plant 16r, and the more widely spaced florets have no significant leaflets poking out from the spikes. The leaves of V. agnus-castus are less serrated and have fewer leaflets than the lower leaves of Plant 16r. Vitex negundo has more distinct serrations than V. agnus-castus, but the leaflets are petioled and the stems are opposite.

Assuming for now that Plant 16r may be Cannabis, it’s difficult to say whether the drawing represents C. sativa or C. indica—both plants are similar in general morphology. Since Cannabis plants can be quite variable, depending on growing conditions and climate, the VM plant might even be somewhat generic, representing both.

Assuming for now that Plant 16r may be Cannabis, it’s difficult to say whether the drawing represents C. sativa or C. indica—both plants are similar in general morphology. Since Cannabis plants can be quite variable, depending on growing conditions and climate, the VM plant might even be somewhat generic, representing both.

We could hazard a guess that the wider spacing of the leaves and larger number of medium-narrow leaflets favors sativa, but that assumes the illustrator knew there were two species and was intending a naturalistic representation rather than a schematic one. Since there are stylistic choices in some of the other VM plants (roots with heads, roots as animal shapes), we can’t assume all the plant drawings are strictly literal. Nonetheless, if this is Cannabis, it’s a pretty good drawing, better than most botanical drawings of the time, and almost as recognizable as a real plant as the viola on Folio 9v.

J.K. Petersen