14 August 2019

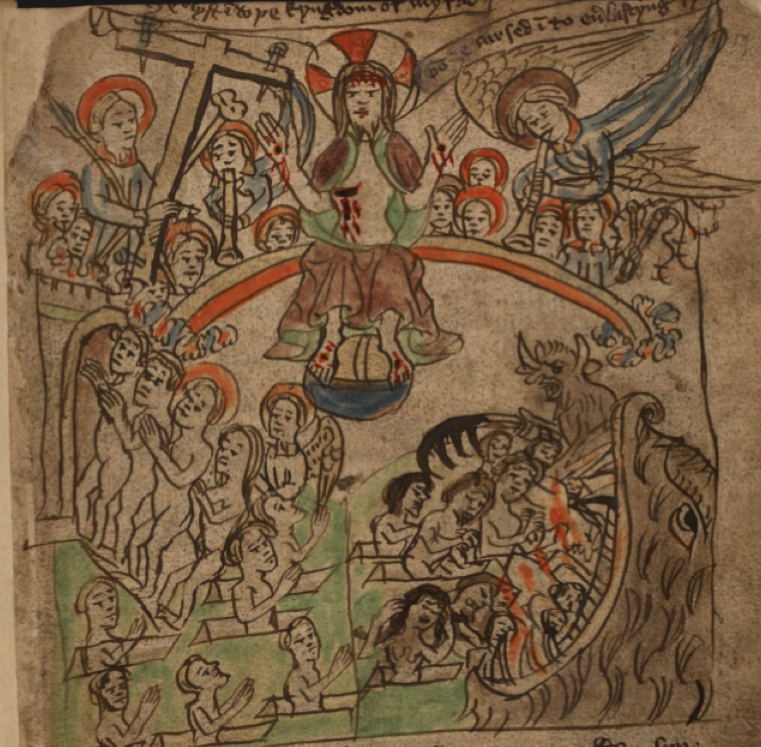

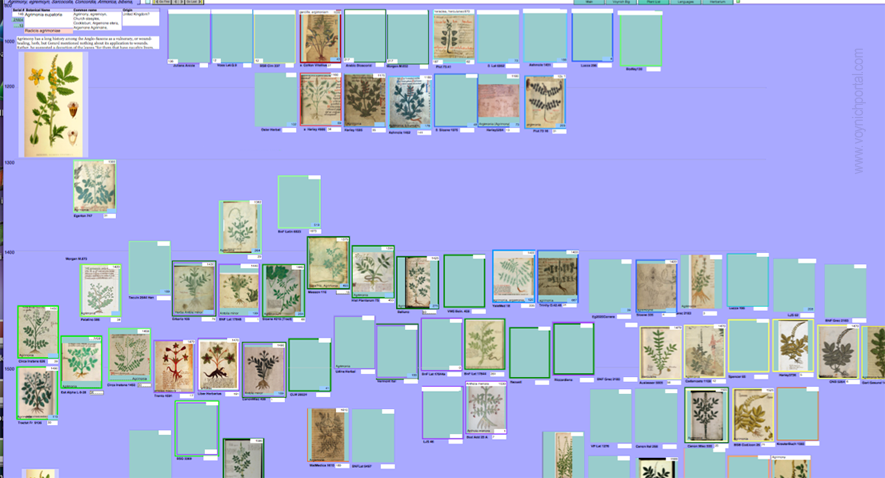

The transition from Judaism is marked in Christian history by the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ. These events are illustrated in ways that were surprisingly similar in distant lands such as Ethiopia, Armenia, and northern Germany. But there were also traditions specific to certain areas, so, I’ve been wondering if parallels exist in the VMS.

Ecclesia

Let’s look at Ecclesia. She personifies the church and shows up in medieval art a couple of centuries before she was paired with the second figure in this drama.

This is how to recognize her…

In these four interpretations Ecclesia carries a wine chalice (which holds the blood of Christ) or a monstrance, which in turn supports the “host”, a round bread-like object symbolizing the body of Christ. Note the cross and two lines on either side lightly inscribed on the host in the image on the right. Sometimes the name of Jesus is abbreviated around the image of a cross, sometimes a drawing of the Christ child is attached to the host (usually in Eucharist drawings).

In the two images on the left, Ecclesia holds a cross-staff. Sometimes she is nimbed, but often the halo is reserved for Mary and St. John and helps distinguish them from Ecclesia and her counterpart. Ecclesia is virtually always wearing a crown:

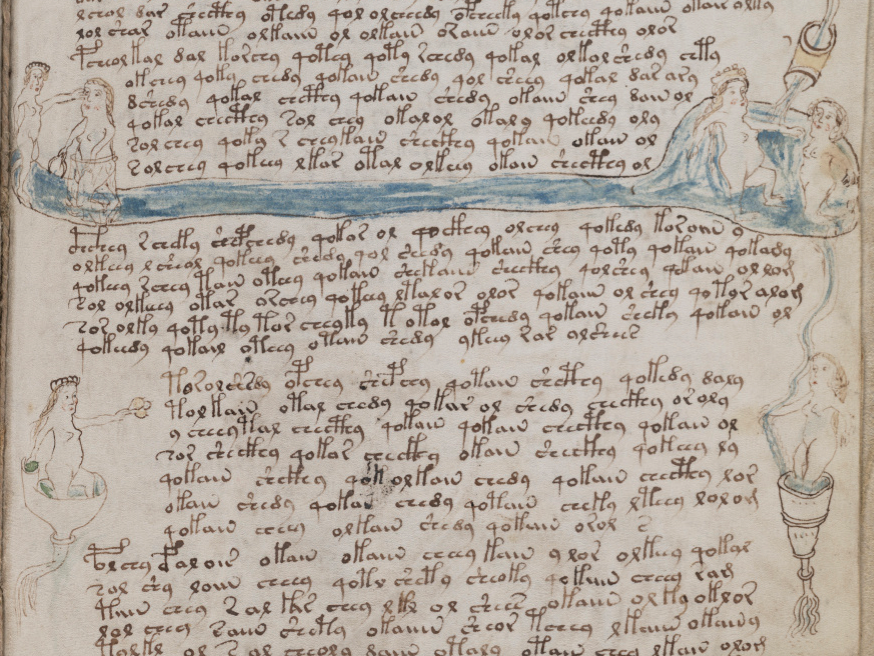

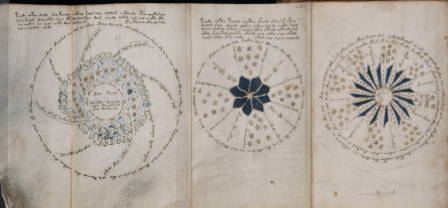

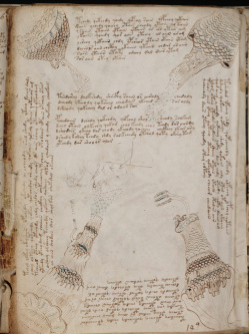

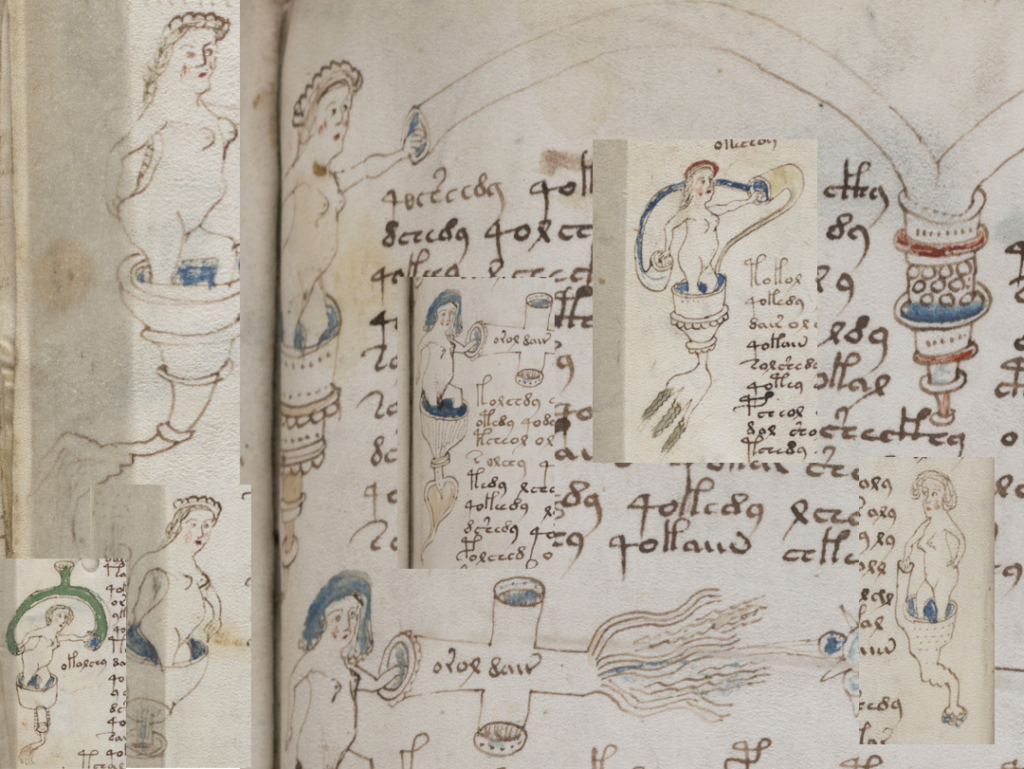

In this VMS image, a nymph holds out a stick with a cross shape. It might be a tool (like a sighting stick) or a cross, or a cross-staff. We can’t tell if she’s wearing a crown. I’m beginning to think the nebuly-like parasol represents religious authority:

Maybe there are other elements on the folio to help identify her, but we’ll come back to that after we meet her partner…

Synagoga

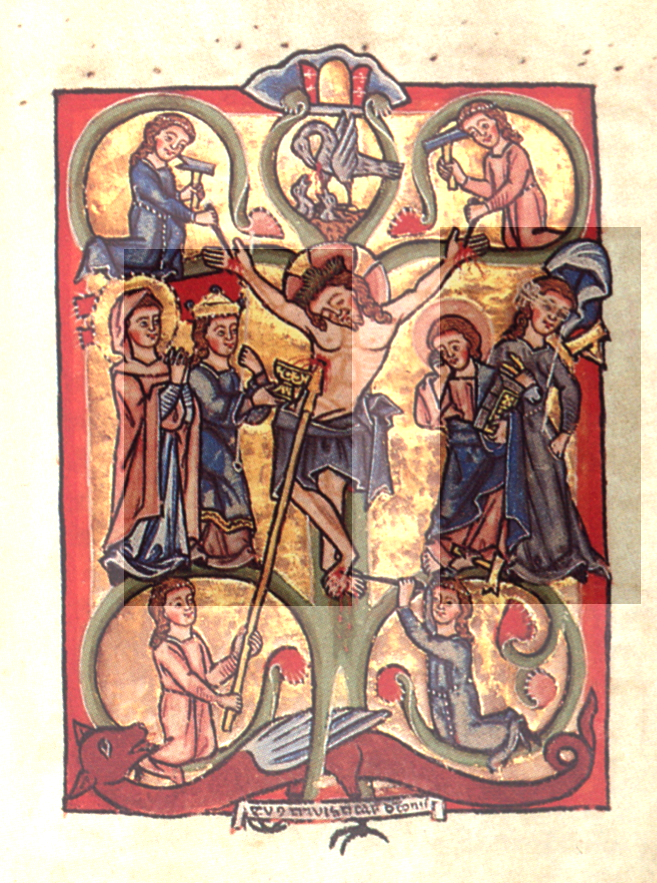

Typically, Ecclesia is paired with another figure known as Synagoga. In a specific illustrative branch of the crucifixion, Ecclesia and Synagoga are paired on either side of Jesus on the cross.

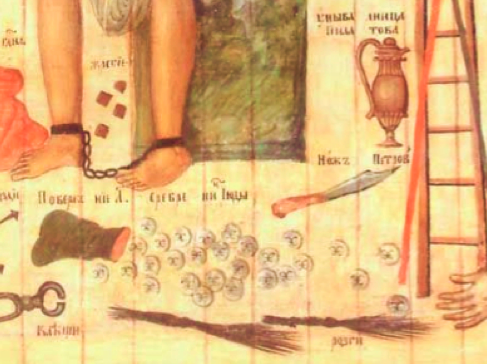

Synagoga is always placed on the right and wears a blindfold (a Christian political symbol of her inability to see the message of the Messiah). She is frequently shown with a tablet in one hand, a broken staff, and sometimes a crown falling from her head. In contrast to Ecclesia, her posture is slouched and defeated:

Early depictions of the two women were not openly hostile but the intended message of the Christian religion being superior to pre-Christian beliefs was made iconographically clear.

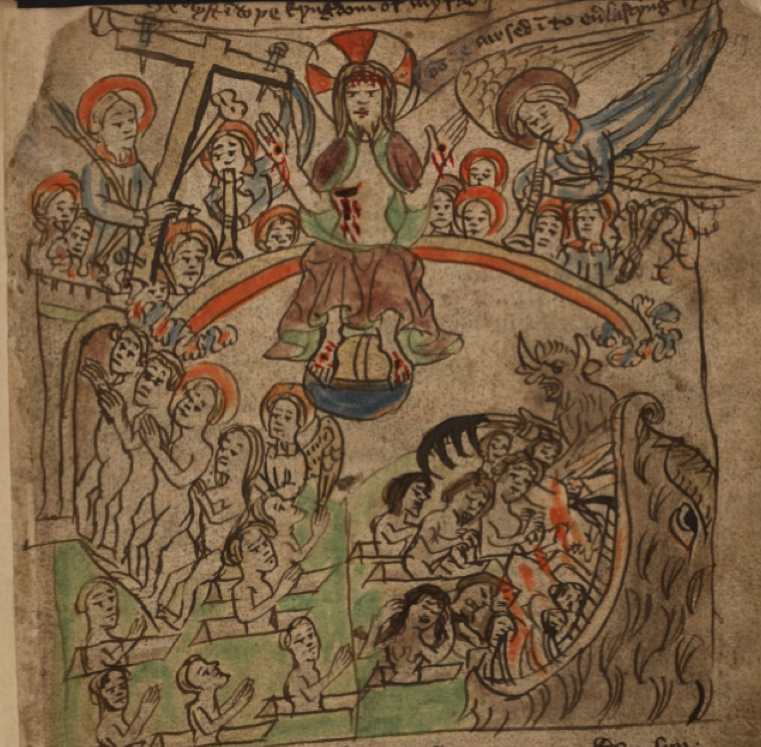

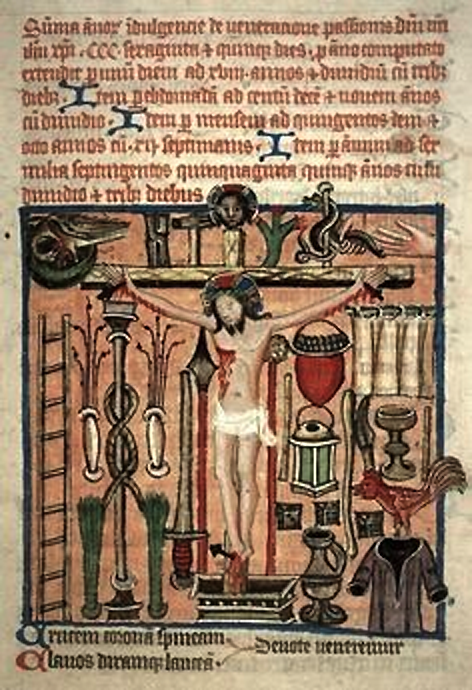

In the next example, Ecclesia is shown in a variety of poses in the top panel. She stands tall and proud, carrying the torch that doubles as Christ’s blood in a wine goblet. On the left is a chalice with the crossed host, and a cross-staff.

In the panel below Ecclesia, Synagoga wears her customary blindfold (a reference to the veil of Moses). She looks tired and beleaguered and has lost her crown.

The odd “thing” in her hand on the far left might be hard to recognize unless you knew the story, but it is the head of a goat or ram, representing ancient rites of sacrifice. In her other hand is something resembling a bell (this is usually a tablet, but this odd detail might be important later). In this case, it is an overturned torch-chalice, like the one in the upper panel, except now it is hanging empty:

Postscript 17 March 2020: Here is essentially the same image (which I personally find distasteful now that I know what it means) from a c. 1420s Rheinland manuscript (Cod. pal. germ. 432):

This scene of the crucifixion shows the two women in context. Ecclesia catches Christ’s blood in her chalice while Synagoga, on the right, is losing her crown:

In an earlier crucifixion from Hildesheim, Germany, Synagoga is identified with a conical hat, while Ecclesia, on the left, wears a crown:

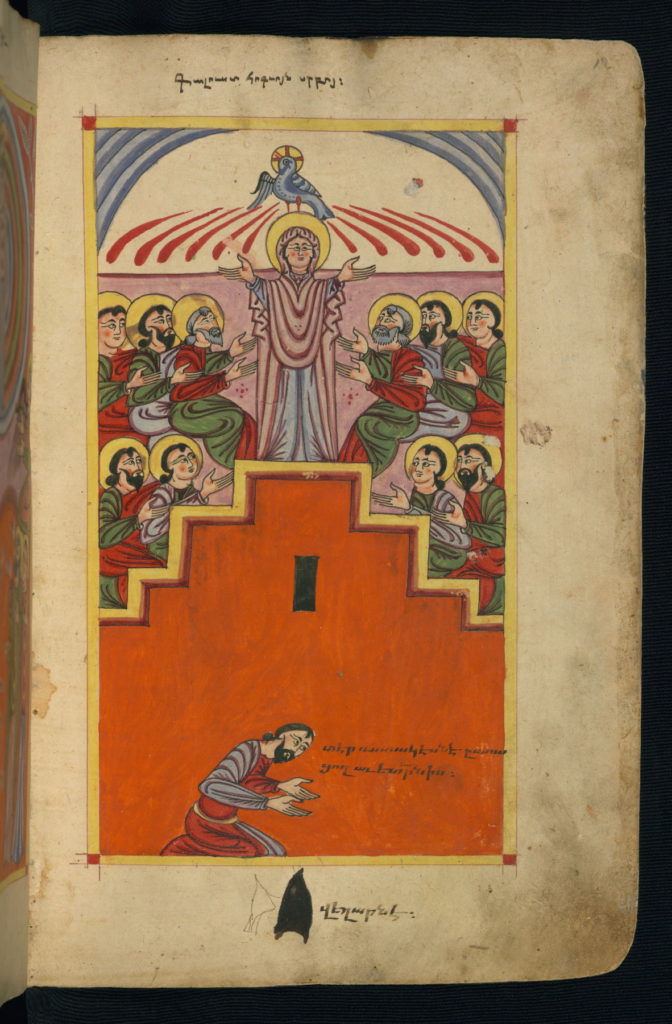

An Armenian manuscript from the 14th century shows Ecclesia with crown and chalice, while Synagoga has had her crown lifted off by an angel. You can view this version on Getty Images.

Sculptural Media

The theme of Ecclesia and Synagoga appears in medieval in church architecture, as in this blindfolded Synagoga with tablet in one hand and a broken staff in the other:

Are Ecclesia and Synagoga in the VMS?

Compared to many medieval manuscripts, the VMS is conspicuously nonviolent. There are smiling animals, clawless felines, and a notable lack of weapons. Yet one of the few images that has been interpreted as violent (at least by some) might, in fact, be our iconic pair.

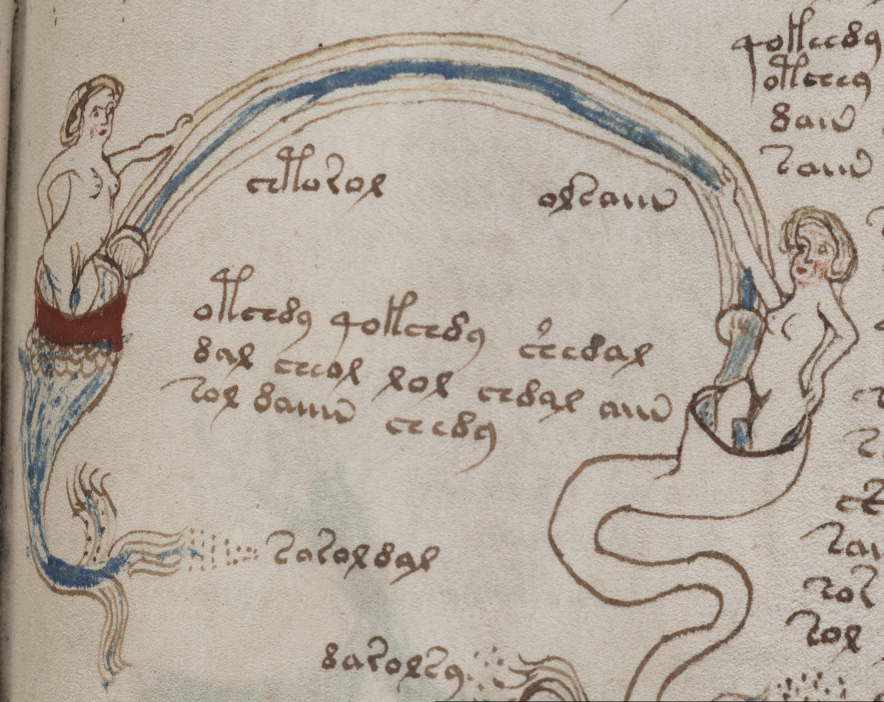

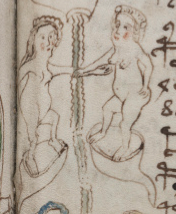

In this drawing on f82r, the nymph on the left looks like she is poking the other one in the eye. But I’m not sure. Maybe she’s pointing at the eye or brushing away a tear. She is wearing a crown or some kind of fancy head-dress. Could she be Ecclesia indicating blindness?

I always thought the nymph on the right was carrying a pair of pincers, or a badly drawn compass. But what if this is Synagoga’s tablet, or an overturned empty torch or chalice as in the Darmstadt manuscript above? If it is an empty torch or tablet, it is artfully hidden in plain sight by not having a dark line across the bottom to distinguish it from the water:

I’m really not sure whether the nymph on the left is pointing or poking out an eye—blinding or indicating blindness in the other nymph. The only somewhat aggressive version of Ecclesia and Synagoga I’ve found so far is this one, by Pisano.

On the left, an angel escorts Ecclesia with her chalice toward the cross. On the right, another angel escorts the aging Synagoga away from the action:

It’s not exactly on the same level of aggression as poking out an eye. Assuming for a moment that the nymph on the right might be Synagoga, can we confirm it by examining the other elements?

Is the “thing” in her hand an empty torch? Or is it a tablet?

If it’s a tablet, it’s a direct reference to Moses in the Old Testament. When Moses was a baby, he was set adrift in a basket so he would not be killed by the king. Could the nymph’s “skirt” be a basket? Is this why her hand looks like it’s inside the rim instead of outside? Is she standing in the river where Moses was found?

Has the illustrator combined Moses and Synagoga, male and female references to the Jewish faith, into one nymph? Is this why several of the VMS nymphs are sexually ambiguous (because they represent more than one thing)?

We know that Ecclesia is usually depicted on the left wearing a crown, Synagoga on the right without a crown (or in the process of losing it) and the nymphs happen to follow the same pattern.

Context

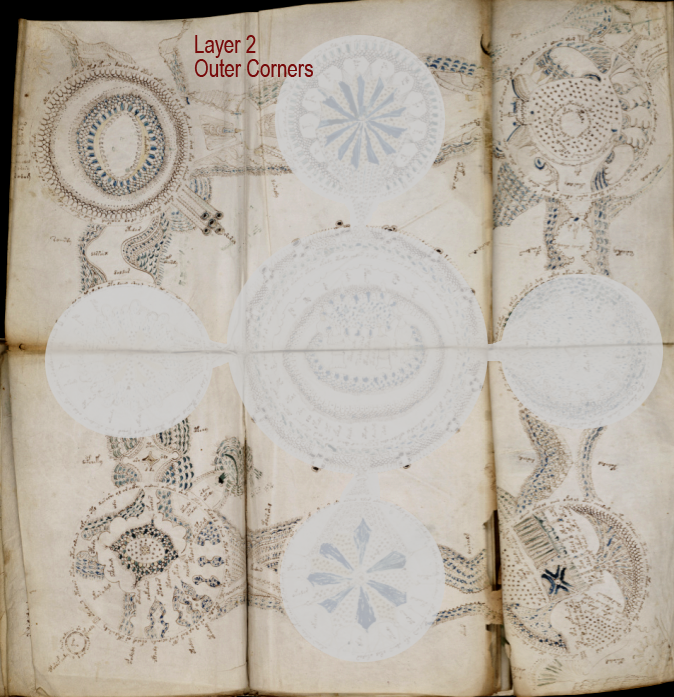

What about the other elements on the page?

I like K. Gheuen’s suggestion that the figures across the top of this folio might represent a story from Ovid. Most medieval scholars were familiar with classical history and myths, including Herodatus, Virgil, Ovid, Hesiod, and others, so I wouldn’t be surprised if this turned out to be Philomela’s story. The part that Gheuens quoted about the king seizing her hair and using it to tie her hands behind her back is especially convincing:

I couldn’t find a better explanation for the series, not even in Bible stories. It’s true that Eve was often drawn with long hair, and the spindle became her avatar when she was expelled from the garden, but I couldn’t find a good explanation for the other figures in relation to Eve.

Would the creator of the VMS have transitioned from Ovid at the top of the folio to Biblical references in the middle? I’m a bit uncomfortable with that idea, but given that the story changes from thread and spindles at the top to water and matched pairs of nymphs in the middle, maybe it’s possible.

So, moving down to the center of the page, we have the eye-poking nymph and a long river linking two nymphs on the right who look like they might be the same pair of nymphs repeated (this would not be unusual in medieval drawings)—the main difference is that the nymph on the far right has no attributes:

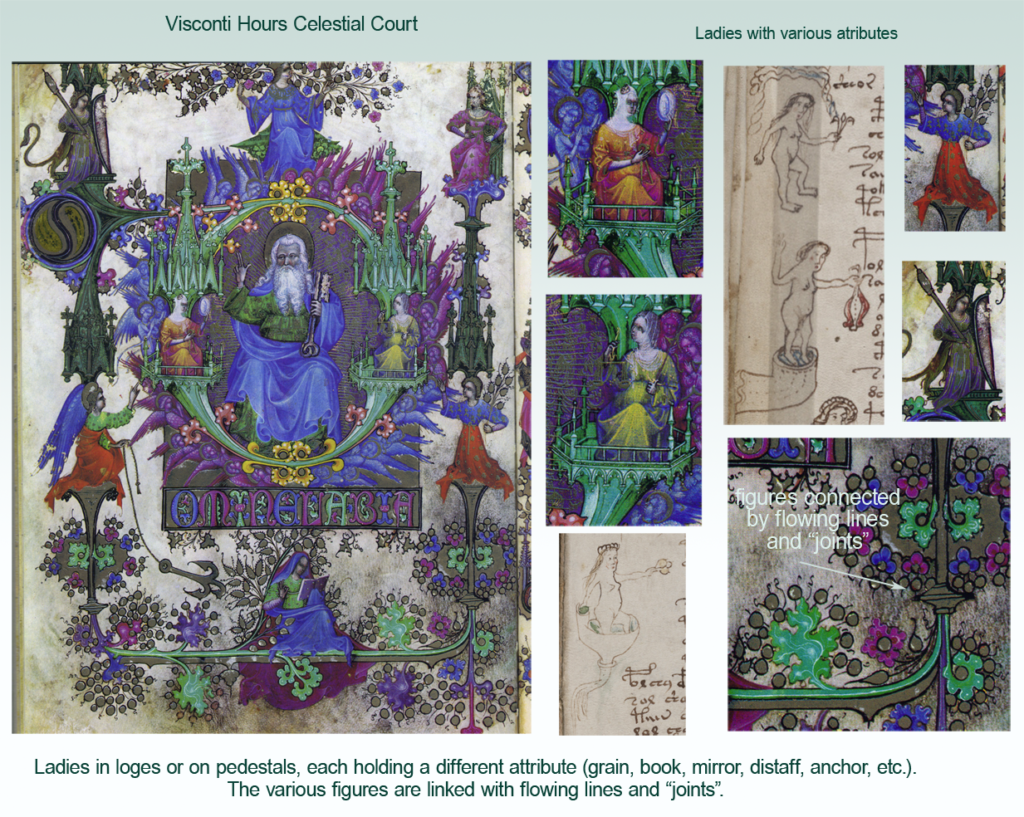

The nymphs on the bottom also look like the nymphs on the middle-left repeated, except that they are now shown separately, in elevated loges, rather than standing together in a river. The nymph on the left is holding another of the mystery items (or possibly three mystery items) but it doesn’t look like a host or chalice.

Can these two figures be found elsewhere in the VMS?

If we move to an earlier section of the quire, there is a nymph on 70r with the same kind of headdress as the nymph on 82r, and her counterpart is also like the nymph on the right on 82r—she’s slightly heavier, has no crown-like head-dress like the nymph on the left. In the earlier image, their arms cross.

If this is Ecclesia and Synagoga, might this symbolize the beginning of the transition from Judaism to Christianity?

More Instances of Possibly the Same Nymph

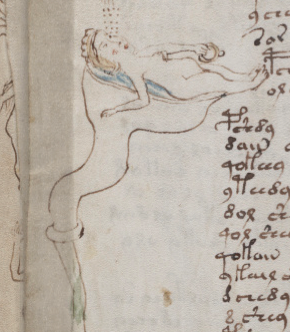

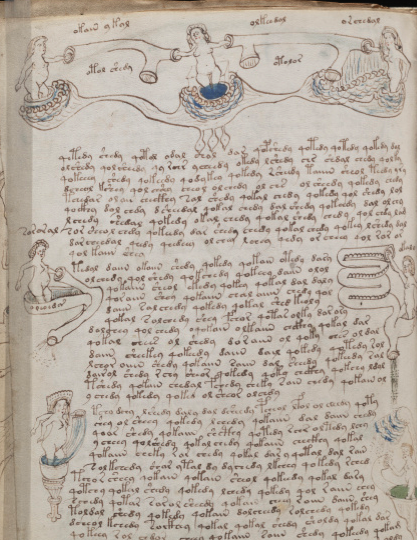

The nymph with the fancy headdress shows up again on 79v and this version really caught my attention because she’s on a wide elevated loge holding a ring, and she’s lying down. She’s not wrapped in a shroud, so I don’t think she’s dead. Is this a marriage bed?

If this nymph is Ecclesia, then the picture fits, because Ecclesia was expressly described in medieval literature as the bride of God.

Above her is the nymph holding out the cross (possibly a cross-staff?). The cross-staff was one of Ecclesia’s attributes, but the celestial parasol is hiding the top of her head, so it’s hard to know if it’s the same nymph.

The nymph on the lower rung is drawn more like the one that might be Synagoga and doesn’t have a head-dress. The position on the lower rung would fit with how she was treated iconographically in Christian literature—slouched, defeated, or in a lower panel as in the Darmstadt illustration.

Is there a larger story being told across a series of folios? The story of a transition from the Old Testament to the New, from the old religions to Christianity, with Ecclesia, the bride of God becoming the dominant nymph and expressing anger that Synagoga doesn’t want to “see” the Christian point of view?

What happens on the rest of the folio? Can it help us confirm or deny any of this?

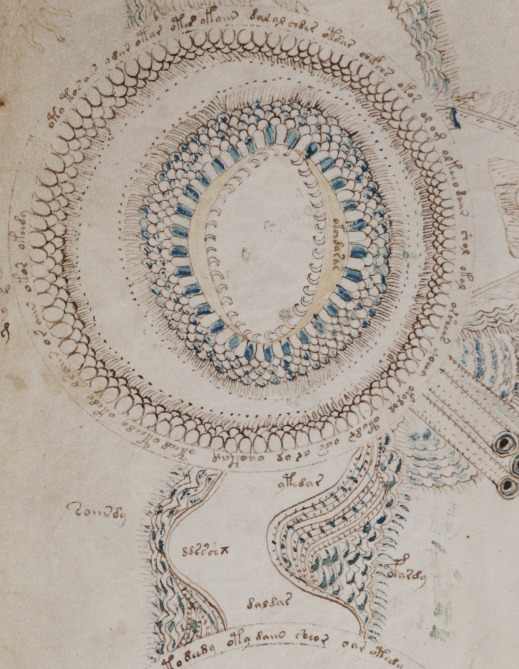

Below the nymph with the ring and the one without a crown is the famous wide-mouthed fish in a pond full of strange critters:

I’ve always been reluctant to interpret this as the story of Jonah. For one thing, it just seems too easy. For another, some of the critters don’t look like sea monsters (except for the giant fish). The Creation cycle often includes a variety of animals, but not a giant fish (and this image doesn’t fit creation stories as well as some of the other drawings of the VMS).

If it’s two narratives rolled into one (if the imagery on the left is a different place or time from that on the right), it would be even harder to guess what it represents. I’m not sure what to make of it, but let’s see if it might be Jonah…

If the nymph in the fish’s mouth is Synagoga (note how the uncrowned nymph in each of these panels has shorter, colored hair and a slightly bigger belly and hips to distinguish her from the one with the longer hair and fancy head-dress), then perhaps the Jonah story is appropriate.

When a storm boils up at sea, Jonah’s companions question him, suspiciously trying to determine who is responsible for unleashing God’s wrath on the tossing boat, but Jonah answers quite simply as a God-fearing man, “I am a Hebrew”. What could encapsulate the identity of Synagoga more succinctly than, “I am a Hebrew”?

Classical Stories Mixed with Bible Passages?

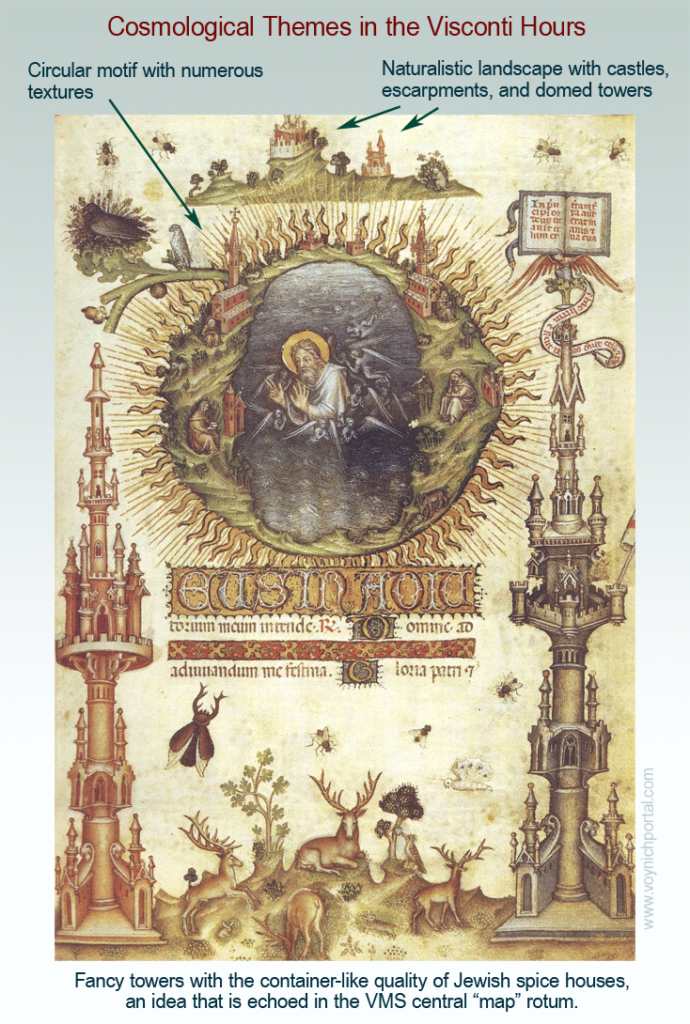

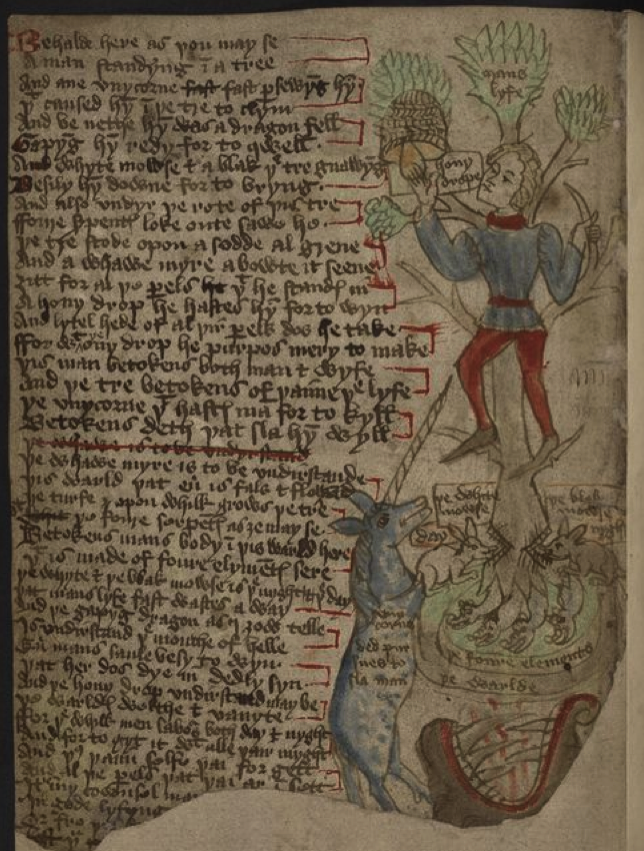

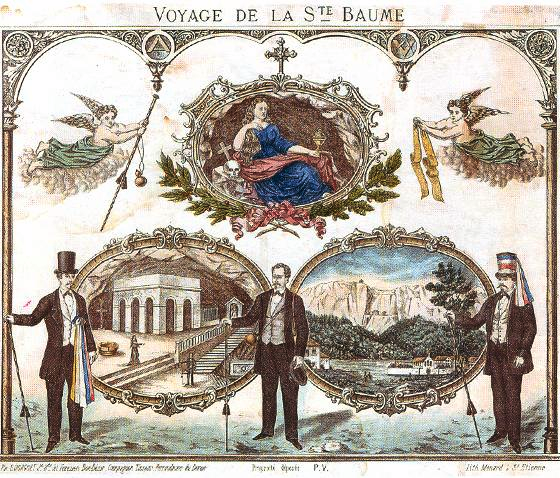

It seemed strange to me that the VMS might mix classical history (e.g., Herodatus, Ovid, etc.) with Bible stories… until I came across Speculum Humane Salvationis, which freely combines them.

In the Speculum Humane Salvationis, which was popular in the 15th century, the story of Adam and Eve, the Deluge, and Anna and the Annuciation are immediately followed by the less-familiar prophetic vision of Astyages, the last king of Media. Astyages dreamed of a vine growing from the belly of his daughter Mandane, a vine that would spawn a boy (Cyrus) to challenge his grandfather for the empire. In a Persian version, Cyrus was suckled by a dog, similar to the infants Romulus and Remus.

Our information about Astyages comes almost entirely from Herodatus. The Bible includes only this one brief reference from the Book of Daniel:

And king Astyages was gathered to his fathers, and Cyrus the Persian received his kingdom.

Connections?

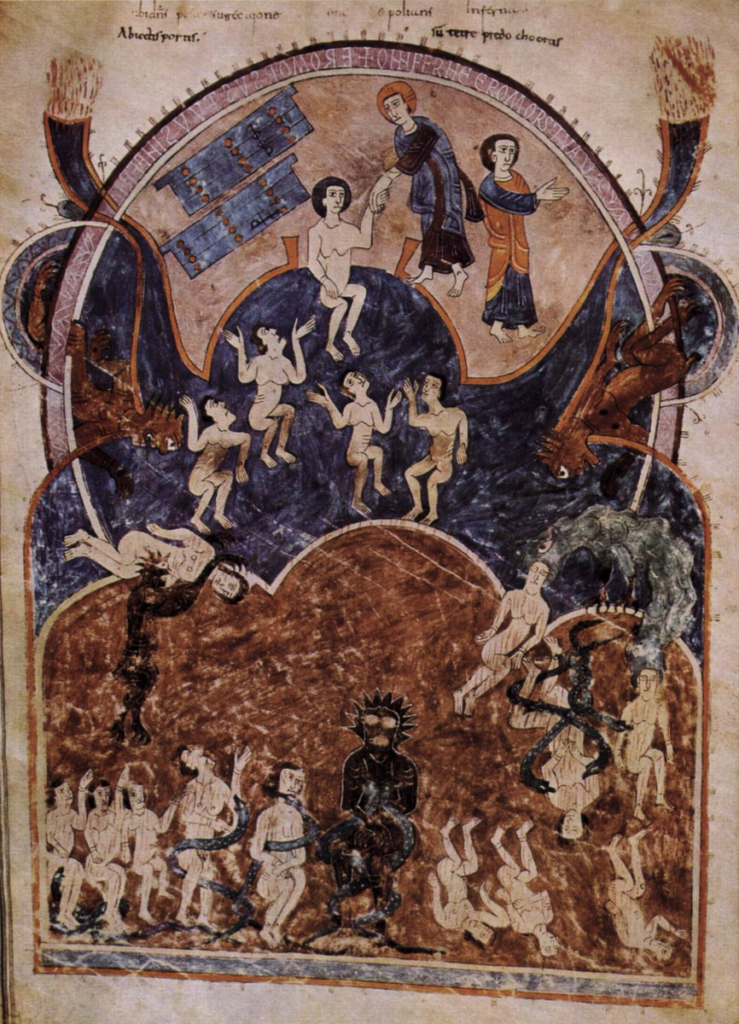

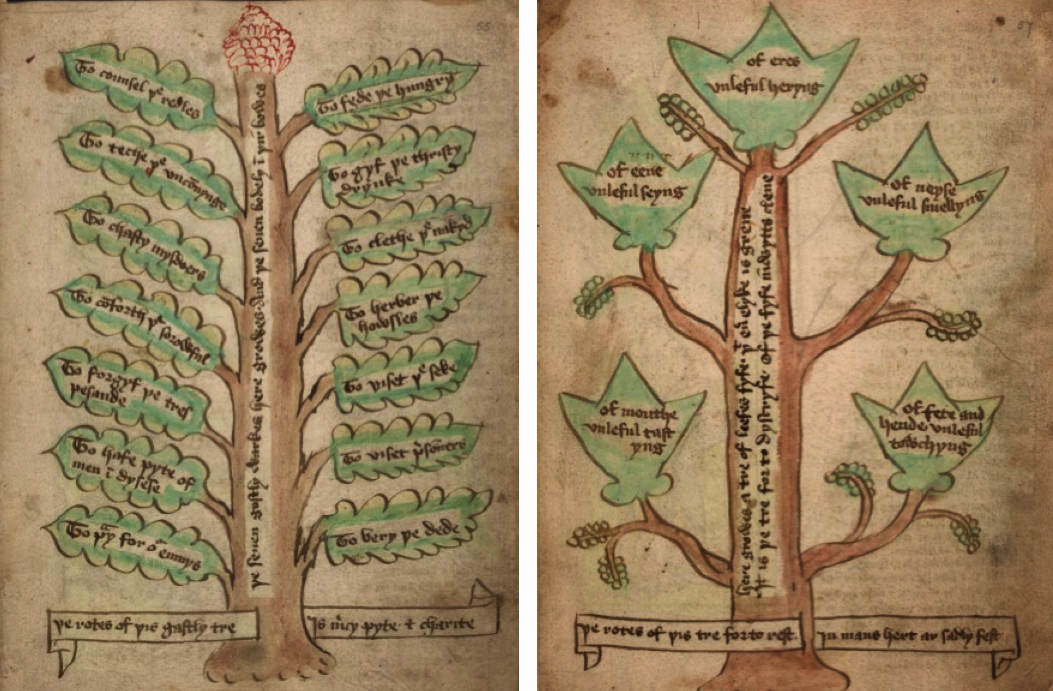

The idea of a vine growing out of Mandane’s belly to symbolize her son’s growth and eventual possession of the empire is echoed in the story of Jesse, in Isaiah 11. Jesse is shown lying down, at the base of the folio, with a vine growing from his “root” (it usually grows from his chest or belly).

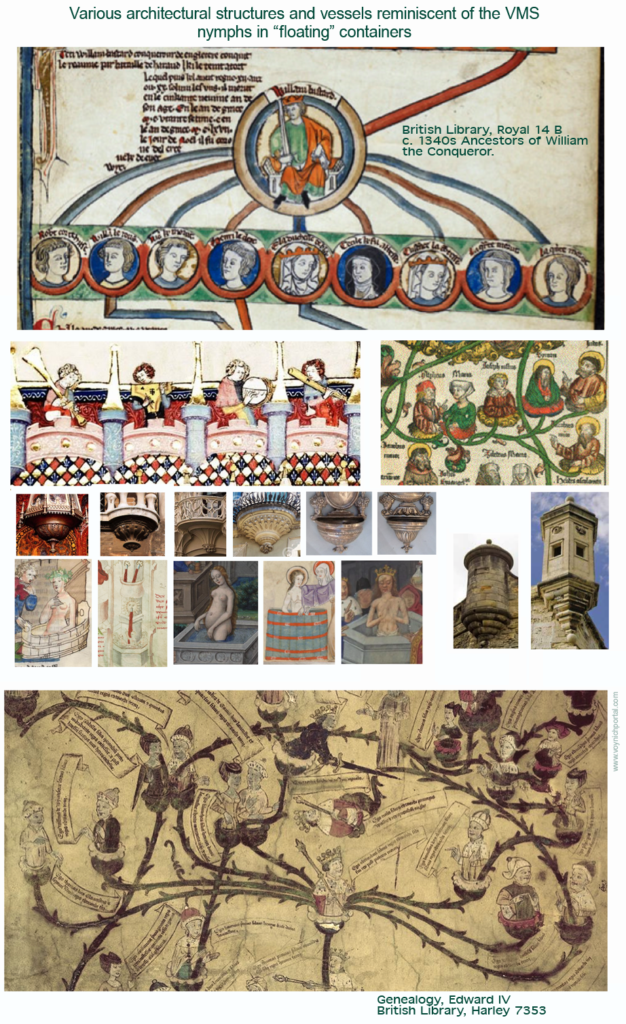

This symbol of biblical genealogy came to be known as the Jesse tree.

I’ve always wondered if the clothed figures around the bull in the VMS zodiac-figures section are related to genealogy. Could it be a VMS version of a Jesse tree?

Jesse trees came in many different formats, some almost menorah-shaped (a reference to the tree of life). Often the figures are shown only from the waist up. But the main difference between a Jesse tree and the VMS drawing above is not the absence of a tree, but the absence of Jesse himself, who is usually shown as a man with a beard under the figures, dreaming.

So perhaps this is not a Jesse Tree, but there might be one somewhere in the VMS, just as Jacob’s ladder might be included (e.g., the image of nymphs one on top of the other within a green “waterfall”).

I have much more information on this line of thought, but it’s far too much for one blog. I will have to split it into two sections.

Summary

I am beginning to believe that some of the VMS nymphs appear more than once in several places, acting out a story that stretches across multiple sections or folios. There is a certain consistency to the way some of the pairs have been drawn.

I am not entirely sure that the pair described in this blog is Ecclesia and Synagoga, but I think it’s possible and I will discuss this more in Part 2. I also think it’s possible that more than one person might be represented by a single nymph, but this is harder to ascertain, so I will tackle that after some of the easier questions have been solved.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2019 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

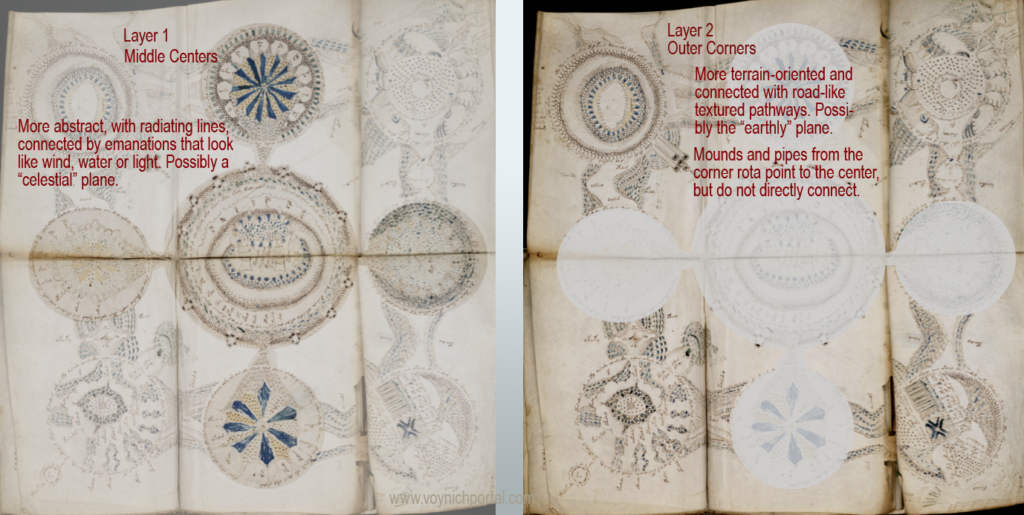

![Emanations from an architectural support (under which is a dove) [BNF NAL 3226]](https://voynichportal.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/HoursBNFNAL3226.jpg)