Monthly Archives: July 2013

Voynich Large Plants – Folio 41v

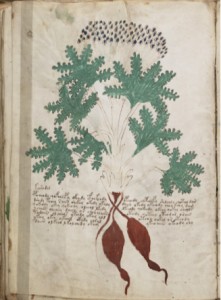

Folio 41v features a plant with tuberous roots that occupies most of the page. The text block covers seven lines that crosses the lower part of the plant, plus a single group of characters above the top left corner of the text.

The roots have been painted a solid brick red and are attached to the stem rather loosely, with strings, as though they might be rhizomes rather than roots or tubers. They have a double bump and a tendril coming from each end.

The leaves are complex, somewhat plamate, with lots of indentations that might be serrates, scallops, or perhaps ruffled scallops or lacinates. They tend to be concentrated at the base of the plant rather than branching up along a stalk.

The stems have been left uncolored and perhaps are lighter than the dark green leaves. They split, at the top, into many smaller stems with flowers or seedheads painted blue. The heads are small and numerous and might be umbellate.

Prior Identifications

It struck me immediately when I saw this, that it might be coriander. The complex leaves and umbellate seed heads look like the coriander I grew in my garden three years ago. I couldn’t remember, however, whether I pulled up the roots at the end of the year to see how they are shaped and I wasn’t certain whether coriander roots could have this yam-like appearance, so I looked around the Web.

It’s rare for me to agree with Edith Sherwood’s identifications, mainly because they seem to focus on one or two characteristics of the plant rather than the whole plant, but this time, she identified this as coriander and it seems possible. I still wanted confirmation, however, that coriander can have enlarged roots, and might have lighter-colored stems than leaves.

I looked at many different varieties of coriander, and couldn’t find any with ovate or dark reddish roots. They were all very parsnip-like, light-colored and carrot-shaped. A few were narrower and stringier. Since it’s my hunch that the VM plants are, for the most part, based on actual observations of plants, it seems unlikely the VM illustrator would make a mistake like this and put the wrong root on a commonly harvested food plant like coriander.

The Plant Hunt

Finding a root like this is not difficult. Ipomoae batatas, the sweet potato, comes immediately to mind. But… finding this kind of root with palmate leaves and a large umbel of small blossoms or seeds, can be a challenge. I discovered many possibilities.

Filipendula vulgaris has many small blossoms at the end of the stem, and similar roots to Plant 41v, sometimes with a smaller nodule at the end, but the leaves are very distinctive, with a small set of leaflets between each of the larger leaves. The VM illustrator probably would have included the leaflets, if this were Filipendula. Also, Filipendula isn’t palmate. The leaves are roughly elliptical and opposite, with a fern-like growth pattern.

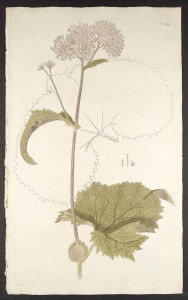

Cacalia, a member of the aster family, is quite a variable plant with almost any leaf shape, from delicate hairlike strands to pinnatisect, palmate, kidney-shaped or heart-shaped leaves, depending on the species. Illustrated here is Cacalia tomentosa from an 18th century herbal. In common with Plant 41v, Cacalia has very erect clusters of umbels and the roots or rhizomes (side-growing underground runners) can be rounded or tuberous and fairly large. Leaves are typically serrated. Cacaliopsis nardosmia has palmate leaves that would be challenging to draw but the umbel clusters are not as numerous as Plant 41v and it’s a west coast plant that wouldn’t have been known to Europe in the 15th century.

Cacalia, a member of the aster family, is quite a variable plant with almost any leaf shape, from delicate hairlike strands to pinnatisect, palmate, kidney-shaped or heart-shaped leaves, depending on the species. Illustrated here is Cacalia tomentosa from an 18th century herbal. In common with Plant 41v, Cacalia has very erect clusters of umbels and the roots or rhizomes (side-growing underground runners) can be rounded or tuberous and fairly large. Leaves are typically serrated. Cacaliopsis nardosmia has palmate leaves that would be challenging to draw but the umbel clusters are not as numerous as Plant 41v and it’s a west coast plant that wouldn’t have been known to Europe in the 15th century.

Parsley (Petroselinum) tends to branch more evenly than Plant 41v but parsnip can sometimes have more rounded tubers and palmate leaves that tend to concentrate at the base. However, parsnip tubers are typically light, not dark.

I didn’t want to assume the umbellate seedlike shapes at the top of Plant 41v were, in fact umbels—the stems leading to the flowerheads are quite long and not as parasol-like as one might expect. Somewhere in the back of my mind, I could remember a weed with a similar shape—one that rattles in the fall, but don’t know if I ever knew its name, which makes it hard to find it on the Net. I also considered that the thick seedhead (if indeed those are seeds rather than tiny flower heads) might represent multiple umbels that are simply hard for an amateur illustrator to draw.

Celeriac, a form of celery, can have large and quite variable roots, ranging from a pale color to a dark yellow, almost orange, but most of the time, the color of the root is light and it’s very knobby, unlike VM 41v, which is more smooth than rough. Celery seeds can be eaten, and thus might be represented as the numerous seed heads shown in VM 41v. Celeriac should probably be considered, but the dark red color of the Plant 41v roots invites us to keep looking.

Levisticum officinale, commonly known as lovage (left) is sometimes known as “Love Parsley” and resembles table parsley in many ways. It has trifolate serrated leaves that look rather palmate, umbellate seedheads that are more vertical than some, seeds that are harvested as a spice, and large, thick, dark roots. The roots are rougher and not as rounded as Plant 41v and the stems tend to branch more evenly than the VM picture, but Levisticum should probably be considered as a possibility.

Levisticum officinale, commonly known as lovage (left) is sometimes known as “Love Parsley” and resembles table parsley in many ways. It has trifolate serrated leaves that look rather palmate, umbellate seedheads that are more vertical than some, seeds that are harvested as a spice, and large, thick, dark roots. The roots are rougher and not as rounded as Plant 41v and the stems tend to branch more evenly than the VM picture, but Levisticum should probably be considered as a possibility.

Carum carvii (Caroway) has fairly upright umbels, distinctive seeds that are used in cooking and baking, frondlike feathery leaves that might look somewhat palmate in an inexpert drawing, and fairly dark thick tap roots. The roots are not as rounded as 41v, and the leaves don’t really match.

Another plant similar to Levisticum and Carum is Myrrhis ( left), known as cicely or chervil. It has umbellate flowerheads that tend to be a little longer and more vertical than some, the roots are large, dark, and sometimes rounded, and the brown seeds tend to stand up. This may be related to the weedy plant I’ve encountered on some of my hikes. The seeds are rather distinctive. One would be very tempted to say Plant 41v is some species of Myrrhis, but Myrrhis leaves are more frondlike than palmate, and larger than 41v. It’s probably a good contender, but may not be a match.

Another plant similar to Levisticum and Carum is Myrrhis ( left), known as cicely or chervil. It has umbellate flowerheads that tend to be a little longer and more vertical than some, the roots are large, dark, and sometimes rounded, and the brown seeds tend to stand up. This may be related to the weedy plant I’ve encountered on some of my hikes. The seeds are rather distinctive. One would be very tempted to say Plant 41v is some species of Myrrhis, but Myrrhis leaves are more frondlike than palmate, and larger than 41v. It’s probably a good contender, but may not be a match.

Crambe maritima (Sea Kale) has palmate, very ruffled leaves that would be challenging for the VM illustrator to draw, along with many round seedheads on vertical stems. It might be a tempting choice, the roots are thickened and dark, but they are not rounded and the leaves are rather large, not small or medium-sized as in Plant 41v.

Astrantia major, Masterwort, an attractive and much-cultivated ornamental, poisonous plant (and traditional medicinal plant) has traits in common with Plant 41v, including serrated palmate leaves, umbel-shaped flower heads, and somewhat thick darker roots. They’re not as ovate as the Plant 41v roots, but they are closer in shape and coloration than Coriandrum.

Astrantia major, Masterwort, an attractive and much-cultivated ornamental, poisonous plant (and traditional medicinal plant) has traits in common with Plant 41v, including serrated palmate leaves, umbel-shaped flower heads, and somewhat thick darker roots. They’re not as ovate as the Plant 41v roots, but they are closer in shape and coloration than Coriandrum.

There is a South American plant that almost fits the bill. Arracacia, Peruvian carrot. It has somewhat ovate roots that cluster and come in many colors. the leaves are serrated odd-pinnate and look somewhat palmate, and the umbels have many distinctive seeds. The leaves are concentrated at the base, rather than branching, similar to VM 41v. The stems can vary from light green to a fairly deep red. One might say it was the best match so far. Arracacia is in the family Apiaceae.

Pimpinella (salad burnet) has serrated, odd pinnate leaves that might be drawn as palmate. The small round seeds are on umbels, the root tends to be a fairly large tap root, and the plant is used medicinally, and as food. However, the root, while ranging from light to medium dark, tends to be more carrot-like than ovate.

Pimpinella (salad burnet) has serrated, odd pinnate leaves that might be drawn as palmate. The small round seeds are on umbels, the root tends to be a fairly large tap root, and the plant is used medicinally, and as food. However, the root, while ranging from light to medium dark, tends to be more carrot-like than ovate.

There are many plants with umbels, small seedheads, thickened roots, and palmate, or palmate-in-the-eyes-of-an inexpert-illustrator leaves, and there is one more worth mentioning. Conopodium majus is a plant with an edible root known as earth chestnut, or pignut. It has odd pinnate, palmate leaves, umbellate flowers, and the underground “chestnut” tends to be brownish-red and somewhat ovate. The leaves are concentrated at the base. The lower part of the stem can be light in color, almost white. The leaves are frondlike and so not a good match for the Plant 41v leaves, but in other respects, it bears consideration.

Summary

It’s difficult to make a definitive identification of this plant, with so many species having umbellate flowers and large roots. It’s probably best to leave the final determination of Plant 41v until more is known about the content of the text.

J.K. Petersen

Large Plants – Folio 41r

Large Plants – Folio 40v

Large Plants – Folio 40r

Large Plants – Folio 39v

Large Plants – Folio 39r

Large Plants – Folio 38v

Voynich Large Plants – Folio 38r

In 2013, I posted some initial impressions of Plant 38r, stating that the “apostrophes” probably represented droplets (sap), but I couldn’t find enough public-domain images to fully explain what I feel it represents (posting an idea is one thing, convincing people that it’s a valid idea is entirely another) and opted to redact it rather than leaving it half illustrated. Since then, many more botanical images have been added to the Web and I finally have enough visual aids to demonstrate the logic behind this choice. — May 3, 2018

Description

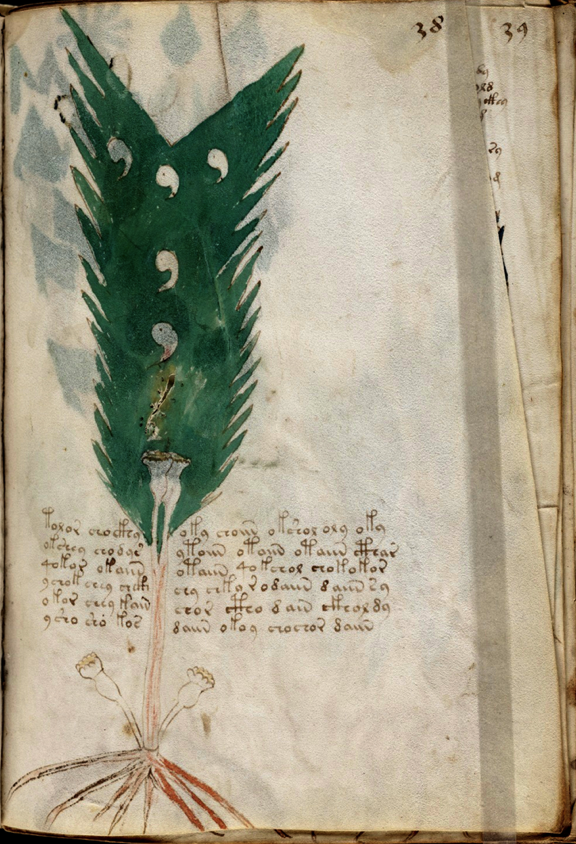

Plant 38r is a tall narrow drawing inhabiting the entire vertical space. Note how it has been slightly crowded toward the left of the folio. The sheet itself is narrower than others, with a long triangular section missing from the top right so that the text from folio 39r is visible.

Plant 38r is a tall narrow drawing inhabiting the entire vertical space. Note how it has been slightly crowded toward the left of the folio. The sheet itself is narrower than others, with a long triangular section missing from the top right so that the text from folio 39r is visible.

The drawing has a jagged green background against which are unpainted yin/yang-like symbols with a single carefully placed dot in each one.

There is a jagged line underneath them where the parchment has a hole that was at one time stitched and, below that, is a pair of vase-like shapes coming out of the stalk with a pale amber color painted inside, perhaps to give it a more rounded 3D look.

The vase shapes converge into a stalk that has been lightly brushed with reddish-brown and the bottom of the stalk sports two additional vase shapes splayed to each side. The base spreads into finger-like roots—brown on the left, reddish-brown on the right. A single paragraph of text fits around the plant where it narrows into the stalk.

When I first saw it, I wondered whether one could interpret the top green part as a river or stream. There are a number of herbal illustrations of water-cress, hepatica, and several aquatic weeds that are drawn within or along river-banks, but there are other aspects to this drawing that suggest the green area is probably representative of leaves rather than water.

I find it interesting that the average number of tokens per line on this folio has been reduced in much the same way as the width of the plant. Perhaps the scribe adjusted the text in anticipation of the sheet being trimmed to make it straighter?

Prior Identifications

I hadn’t seen any prior IDs at the time I worked out an explanation for this plant but it strikes me as metaphorical in some ways and literal in others and when I started exploring herbal manuscripts, I saw a pattern that might account for its features.

I think the height of Plant 38r, which touches the top of the folio and runs off the bottom edge, might be an indication of scale. The green area has a feather-, palm-, or fern-like quality, but if it’s meant to be a large plant, then some relationship to palm trees (or trees or large shrubs with fern-like leaves) seems more likely than allusions to feathers.

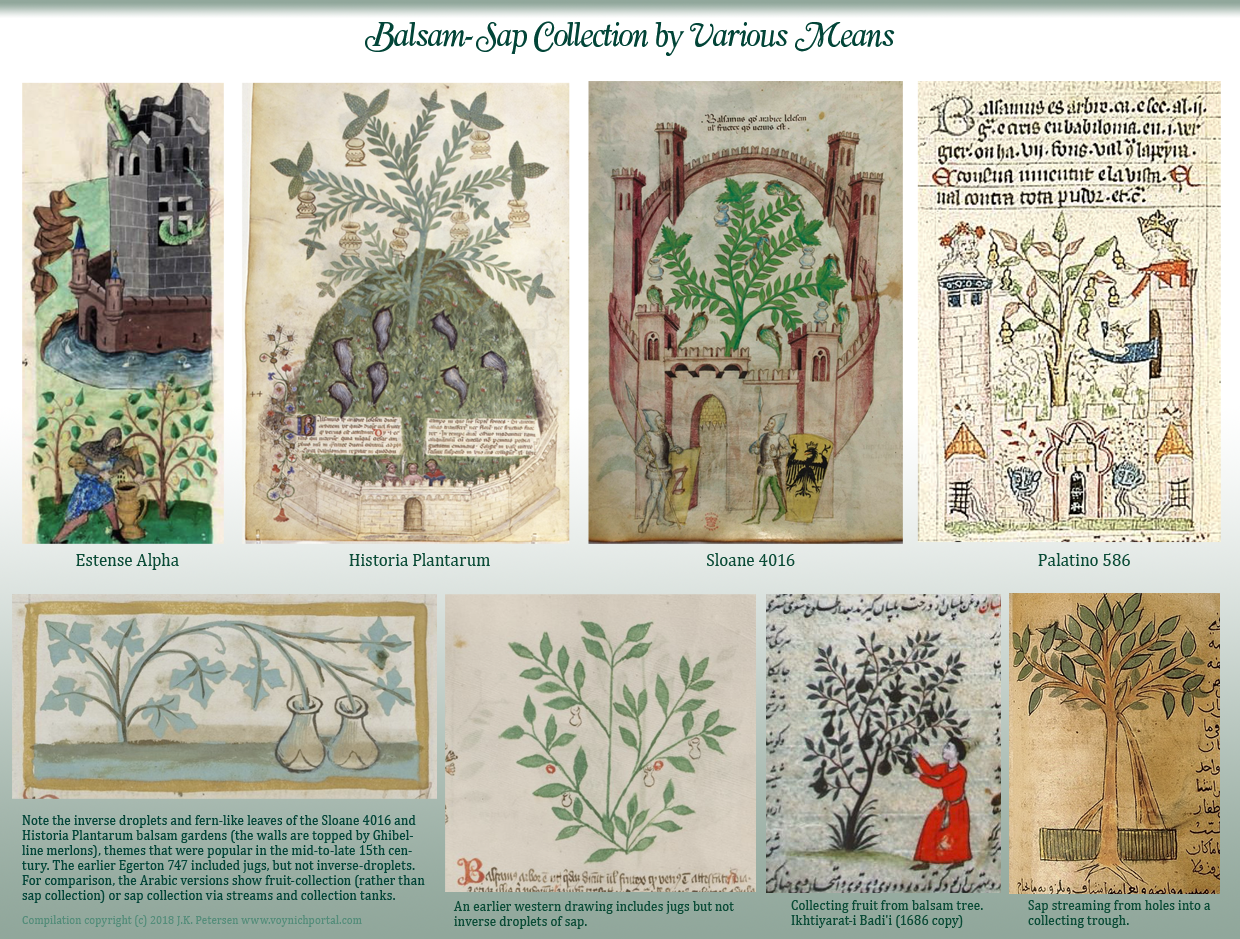

So, imagine for a moment that the green area represents leaves or a garden and the yin shapes are droplets, then the vase-like shapes beneath them might simultaneously represent flowers and receptacles for collecting sap. Sap was harvested from quite a number of plants, including date palms and the rare balsam tree, which is said to have been cultivated within guarded and gated gardens. The saps were variously used as sweeteners, perfumes, and medicinal resins.Thus, it’s not surprising that quite a number of herbal manuscripts include drawings of walled gardens and jugs for collecting sap, sometimes hung on branches, other times held in the hands of the workers [click to see larger].

Note how the droplets are drawn, with the tail facing down, the opposite of what one would expect if they were falling. The VMS drawing orients them tip-down, as well. Note also the fern-like way some of the leaves are drawn, even though balsam trees don’t immediately strike one as fernlike until one looks closely and simplifies their basic structure. The fern-like approach was more common in the 15th century. In the 14th century, the leaves were usually elliptical.

How Herbal Traditions Relate to the Voynich Plant

I am fascinated by the possibility that the VMS drawing depicts a plant that is harvested for sap, because there is still considerable debate over whether the VS plant images follow eastern or western traditions (personally I don’t think the dividing line is as cut-and-dry as some people suggest, since there was considerable copying in both directions, but there are some overall patterns). For example, the theme of vines twining around plants with oak-like leaves that I blogged about in 2013 is found in western manuscripts, but is it a solitary example (or a coincidence)? or are there several drawings in the VMS whose traditions can be identified?

I am fascinated by the possibility that the VMS drawing depicts a plant that is harvested for sap, because there is still considerable debate over whether the VS plant images follow eastern or western traditions (personally I don’t think the dividing line is as cut-and-dry as some people suggest, since there was considerable copying in both directions, but there are some overall patterns). For example, the theme of vines twining around plants with oak-like leaves that I blogged about in 2013 is found in western manuscripts, but is it a solitary example (or a coincidence)? or are there several drawings in the VMS whose traditions can be identified?

As far as I can tell, the inverse-droplet-and-jug theme is western, and wasn’t prevalent until the 15th century. You might notice that the Arabic manuscript included in the compilation above depicts sap collection in quite a different way, with liquid streaming from holes in the tree into a collection-trough at the base—no vases or droplets. The image to its left shows no sap collection at all, the “jugs” are actually fruits being harvested (probably Momordica “balsam apple” which is different from the resin-balsams). I am still keeping my eyes open for non-Western manuscripts with jugs and inverse-droplets but haven’t seen any yet.

As can be seen from the examples directly above, 14th-century images of balsam don’t typically include inverse-droplets (although sometimes they include vases or buckets), and tend to focus on naturalistic aspects of the plants. By the 17th century, accurate drawings of plants had largely superseded illustrations that incorporate the use and environment of the plant. So, the time period during which inverse-droplets were popular in herbal manuscripts is important to VMS research because it is temporally similar to the century during which crossbowmen appeared as Sagittarius in zodiac illustrations.

Why does the VMS drawing have dual-colored roots? I think it’s deliberate, not just haphazard paint application, but I’m hesitant to interpret it too soon. I’ll hazard a preliminary guess, however, that it might be because the Commiphora that produces Balm of Gilead and the Commiphoras that produce myrrh are quite similar, are harvested the same way, and are variously called “balsam” or, perhaps, that both balsam and date palm saps are represented.

Summary

Vase-like Commiphora bud [Photo detail courtesy of toptropicals.com]

If the VMS drawing represents balsam, or some kind of sap that is harvested like balsam, then it follows tradition in a number of important ways: it’s somewhat fern-like, includes a reference to collecting-vases, and includes droplets with their tails pointing down, all characteristics found in manuscripts of the early/mid-15th century. But it is also different in some significant ways. It is greatly simplified, includes no gates or castles, and yet has something lacking from the other medieval drawings… the unusual little flower “vases” characteristic of balsam trees, a detail that only someone interested in plants would notice because these buds quickly turn into little knobs. I’ve said many times that I think whoever drew the VMS plants wasn’t just a copyist, that it was someone who knew a few things about plants, and the addition of these buds seems to point in that direction.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright July 2013 and 3 May 2018 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved