Note, for example, the simple palette, rotum-with-face, and text written in circles. It’s a book of knowledge that covers many subjects, including Creation, sun and moon charts, ancient myths, former rulers, a wonderfully decorative (but very short) section on plants, real and mythical beasts (including a road-kill lion intended to represent a crocodile), Jerusalem, a lapidary, a history of nations, genealogies, alphabets, and number systems.Lambert St. Omer’s Liber Floridus is a delightful volume that I saw years ago, but which always draws me back because of a number of haunting resonances with the VMS.

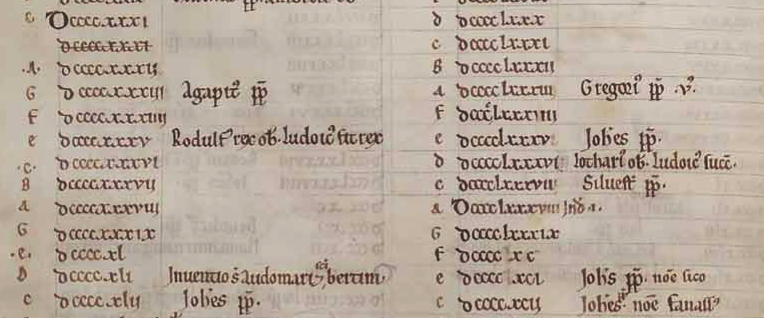

If you glance through it, you will see that the calendars and timelines are laboriously indexed with Roman numerals:

In previous blogs, I’ve written about ancient languages that used letters for numbers instead of separate glyphs for numbers. Similarly, the Romans used the letters M, D, C, X, V, I as both letters and numbers. Sometimes dots or a line were drawn above the characters so they would not be mistaken for letters. In some languages, the placement of the dots (or the number of dots) indicated the place-value of the character (e.g., hundreds or thousands).

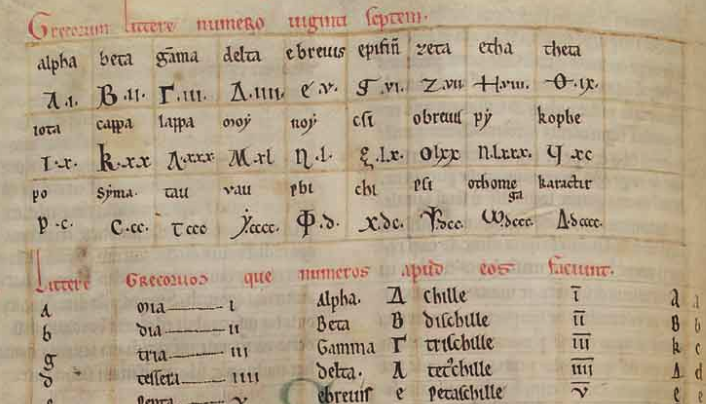

Most people probably zoom past the Liber Floridus chart on folio 55v, but it’s worth a second look because it describes the correspondence between Greek and Roman numerals.

Glance through it and you can see that the Greek system is more compact. For example, the single character tau (“t”) represents three hundred, which would be written as three characters (CCC) in Roman. It’s a trade-off… Greek takes less space to write (and probably saves wear and tear on the scribal hand), but requires more memorization.

Note that early Roman Numerals were “additive” in the sense that the number 9 was sometimes written as VIIII (rather than as IX):

As a small detail of interest to VMS researchers, the “a” in the left column is written 1) with a crossbar on the top rather than in the middle, and 2) without a crossbar. These forms are quite common in Coptic Greek and also in a number of early Latin texts. This shape was sometimes used for the letter “a” and was almost indistinguishable from the Indo-Arabic number 7 or Greek lappa/lambda. This shape is found in the VMS, as well, as one of the uncommon characters.

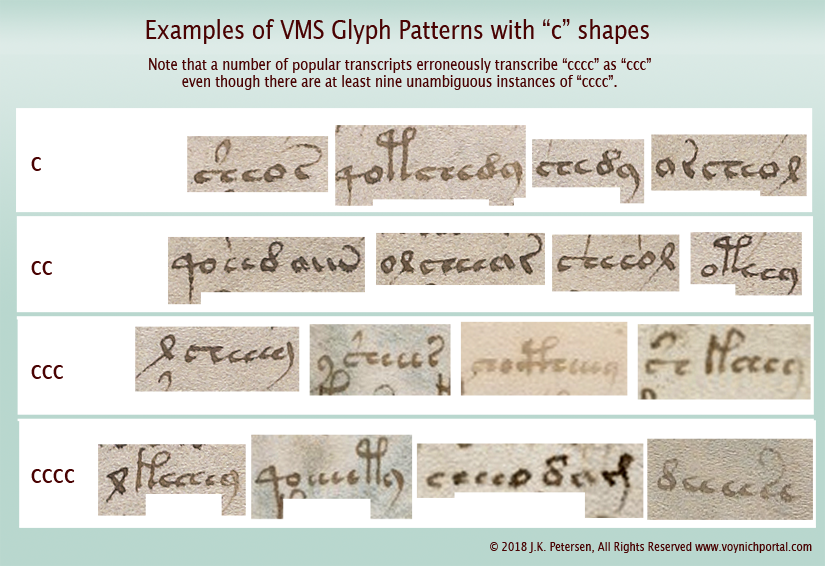

I’ve already pointed out similarities between the VMS and Roman Numerals in a previous blog, and how benched characters represented numbers in Greek and early medieval Latin, so I won’t repeat them here, but I would like to reiterate that patterns c, cc, ccc, and even cccc all occur in the VMS. Here are a few examples:

Linguistically, one doesn’t usually expect to see the same letter three- or four times in a row, but there could be a number of explanations for the uncommon “ccc” and “cccc” patterns. They might represent

Linguistically, one doesn’t usually expect to see the same letter three- or four times in a row, but there could be a number of explanations for the uncommon “ccc” and “cccc” patterns. They might represent

- the end of one token concatenated to the beginning of another, or

- symbols, modifiers, or numbers (similar to Roman numerals), or

- minims disguised as curves, or

- biglyphs. I have mentioned in previous blogs that “cc” represented the letter “a” in early medieval texts and, if superscripted, sometimes referred to the “u” sound (especially when combined with “q”), so biglyphs that stood for a single letter did exist in early Latin. Thus, “ccc” could represent “ac” or “ca” in early medieval Latin, and “cccc” could represent “cac” or “aa”. Note how some of the VMS “cc” combinations are more tightly coupled than others.

A Century of Transition

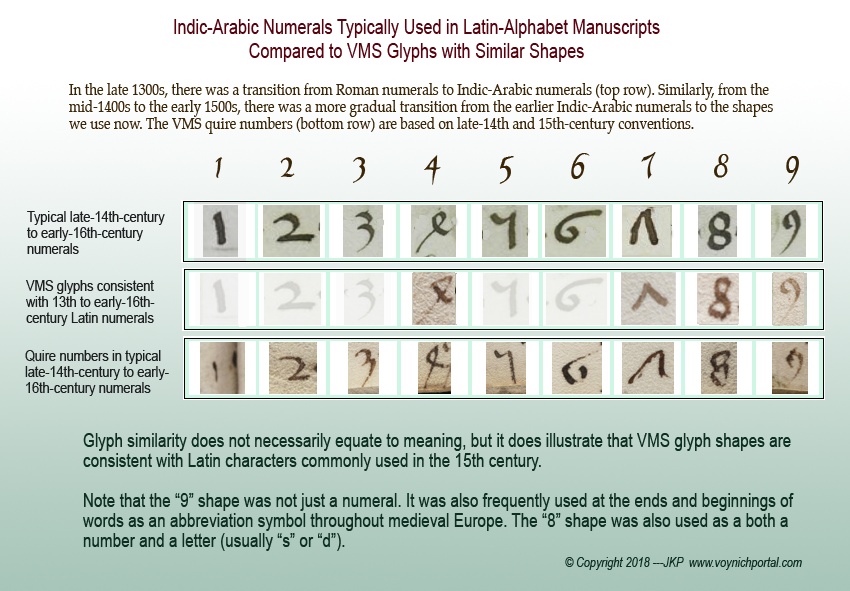

By the late 14th century, Roman Numerals were giving way to Indic-Arabic numerals, the system that was used to write the VMS quire numbers. Several of the VMS glyphs in the main text are the same shapes as Latin numerals, including 4, 7, 8, and 9:

In Latin, all of the VMS “numeral” shapes can double as letters:

In Latin, all of the VMS “numeral” shapes can double as letters:

- The “7” that looks like a caret sometimes stood for “a”.

- The “8” often stood for “s” or “d”.

- The “9” symbol could be a number or a very common Latin abbreviation used at the beginnings and ends of words.

- In early medieval Latin texts, EVA-l (numeral “4”) was used as an abbreviation symbol, a convention that had mostly disappeared by the 15th century.

Thus, three of these four glyphs were in common use as both letters and as numbers in the 15th century, which makes it more difficult to guess how to interpret them in the VMS. When you factor in the position-dependency of Roman numerals the similarity to the construction of VMS tokens cannot be easily dismissed.

Transitional Greco-Latin Forms

For centuries, Latin manuscripts made use of Greek scribal conventions.

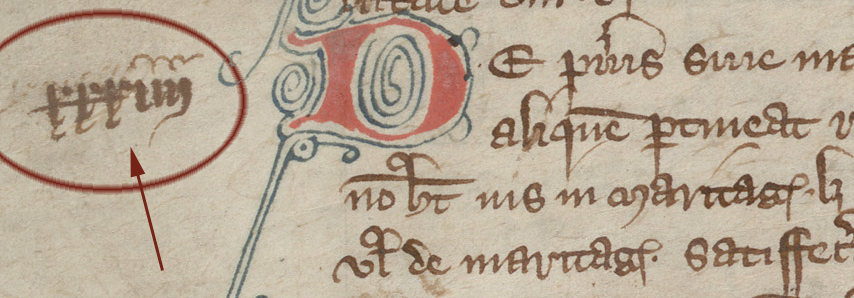

Here is an example of a notation that might help relate some of the examples I have shown in previous articles to those I have posted above. Other writers almost never comment on these marks, partly because they are concentrating on pictures and the primary text, and partly because most people can’t read them. I am, however, fascinated by snippets in the margins because many of them shed light on medieval conventions.

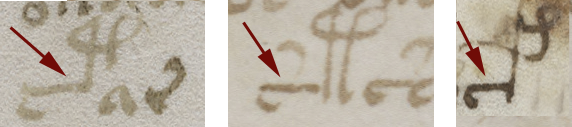

From a 14th-century book of statutes (Berkeley HM 923), note the marginal notation on the left: If you are unsure of what this represents, I’ll break it down for you…

If you are unsure of what this represents, I’ll break it down for you…

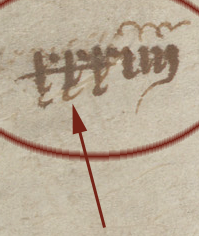

That’s not a “y” at the end, the resemblance is superficial—these marks stand for a Greco-Latin numeral (I say Greco-Latin because the Roman numerals are organized in the Greek style). The strokes at the end represent four “i” characters (the number 4)—it was tradition to lengthen the tail of the last “i”.

Now look at the left side. Notice how there are three characters that resemble “r”? Each one stands for Greek rho, the symbol for 100, Romanized to look like a Latin “r”. Note the line through the characters similar to the crossbar on benched gallows in the VMS.

I have shown examples of this form of benching in earlier blogs and I include an additional example of a benched-rho on a Greek coin (right). Note also the slash on the right.

Adaptation of Greek forms wasn’t always perfect. In a few Latin manuscripts of the 13th century, a benched-P-shape sometimes diverged from its Greek roots to represent the number 4 instead of 100. This may have been a corruption of Greek delta (4) which was sometimes written with extra descending hooks that resembled a bench. Thus benched-rho and delta with hooks might have looked confusingly similar to a Latin scribe. Greek theta (number 9) was also sometimes written with hooks to resemble a benched character. In other words, when manuscripts were translated from Greek to Latin, sometimes the original meaning was retained, and sometimes only the shape remained. In either case, the result was a traditional bench shape associated with a number.

Latin manuscripts of the 13th and 14th centuries sometimes had a single “c” on the left (rather than on both sides) for the number 4 (Ref. Gerlandus De Abaco and BNF Ms Lat Fds St Victor 522). In fact, it’s hard to tell if they are meant to be benched rho, or a Latinized rho with only the left part of the bench. Note these examples in the VMS that show a similar dynamic in terms of the half-bench:

In languages that use Latin characters, crossbars and benching were applied to both numbers and words.

The Mysterious Foot on Some of the VMS Ascenders

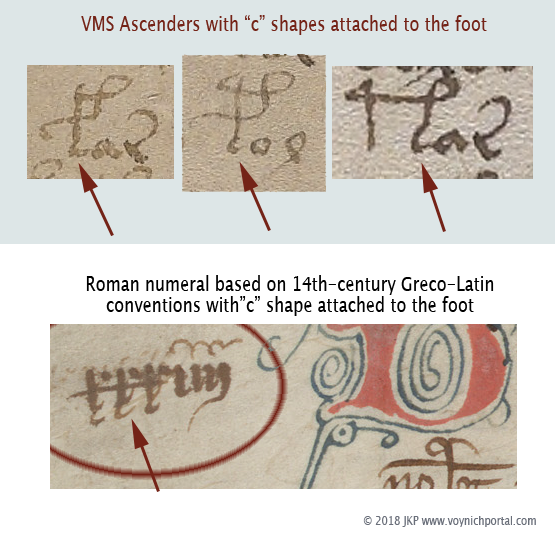

Here comes the important part… As far as I know, there is no previous explanation of this glyph-shape by any VMS researcher…

Look at those tiny tails on the bottom of the “r” chars in the Huntington marginal example. The manuscript was written in early Anglicana script, which has many right-swooping flourishes on descenders, so this would be easy to overlook as an embellishment, but if you are familiar with the Greco-Latin evolution of numerals, you know that these are not flourishes, but “c” characters, the Roman glyph for 100.

Look at those tiny tails on the bottom of the “r” chars in the Huntington marginal example. The manuscript was written in early Anglicana script, which has many right-swooping flourishes on descenders, so this would be easy to overlook as an embellishment, but if you are familiar with the Greco-Latin evolution of numerals, you know that these are not flourishes, but “c” characters, the Roman glyph for 100.

The two most commonly benched chars in Latin manuscripts using Greek conventions were rho (which resembles EVA-p when written in the Greek style) and tau (which could possibly be the inspiration for EVA-T). Here are examples of the same “c” shape in the same position in the VMS.

As has been mentioned, Latin scribes did not always retain the full meaning of the text they were copying. In Greek, when numbers were combined, they usually had additive or multiplicative effects. In Latin, the combination of characters didn’t always add up mathematically in the same way as they might in Greek. You have to look at context to figure out whether the combination of rho and “c” is simply a way of relating the Greek and Latin numerals as the same thing, or whether they must be multiplied to represent a larger number.

The Greek convention of combining shapes wasn’t limited to numbers. The system was used for letters as well, especially when a name or word had to fit in a constrained space. As an example, look at the characters on the left.

The Greek convention of combining shapes wasn’t limited to numbers. The system was used for letters as well, especially when a name or word had to fit in a constrained space. As an example, look at the characters on the left.

The first letter is “o” and you might think the second one that looks like a “p” is rho, but in fact the next letter down (the one that looks like a bench but which represents pi when read as a letter) goes first, and the letter it crosses comes next, so that we have “o pr odro” finished off with an angular slash across the base of the bottom rho, which represents a common ending (in this case “mos”). Together it reads “o Prodromos” which refers to John, Baptist. When writing Greek acrophonic numbers, certain rules of precedent were followed, so the reader would know which parts stood for tens, hundreds, or thousands. The rules for text were looser, however, since a name or word could usually be puzzled out by context, and aesthetics sometimes came into play, as well.

Summary

I have much more information on this topic but unfortunately, I’ve run out of time and this is already long, so I will continue later.

J.K. Petersen

© 2018 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

JKP,

your r or rhos with c extensions are x’es or Roman 10’s, your Huntingdon example is a Roman xxxiiij or Arab 34 and I am quite sure it is nothing to do with Voynich c ascenders

You know what, Helmut, you bring up a good point. I have examples that tuck the “c” underneath, a number of them, some of which are under the “bench” (the Greek letter pi used as a number) and I grabbed the wrong one. I will try to find time to correct this, as the concept is sound, there are examples of transitional Greek-Latin numbers with this construction.

I am mainly interested in the relationship between the Greek acrophonic traditions that were (imperfectly) carried into Latin manuscripts and will try to find the other examples (which are less ambiguous and which show some of the other traits of VMS benched characters) and post them.

Thank you for your comment.

Wow. Just wow. This is certainly good research in my opinion. I’d say you’re slowly puzzling towards the full picture. I can’t wait to see more on this topic.

Was it Brigadier Tiltman that suspected the aiir – groups might be numbers?

I don’t know who was first, Dennis, but the similarity to Roman numerals has no doubt been noticed by many people. In a previous blog, I went so far as to suggest that other VMS glyphs might possibly be interpreted as companion numerals (D, M, V, etc.) and I don’t know if anyone else has done this.

Even if they are similar, however, the challenge is to determine how deeply the similarity goes in terms of structure and whether it’s possible to extract meaning from these patterns. So far I have only posted about glyph origins in terms of shape and position, and haven’t yet had time to write about interpretation which, in the end, is the most important part.