15 June 2019

There’s been a fervor of renewed interest in the VMS mystery animal on folio 80v (including a post about the catoblepas on Nick Pelling’s blog), so I looked at the folio again (and glanced back through my blogs) to see if there was anything that could be said about the critter that hasn’t already been thoroughly investigated.

Looking at the Details

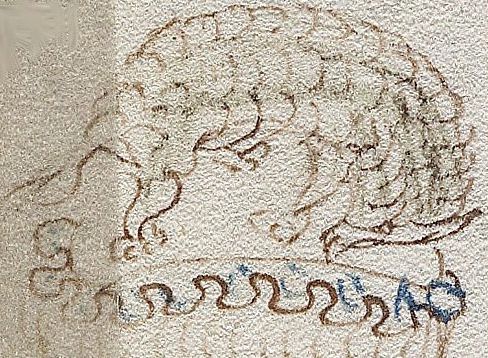

The mystery animal usually goes by the working name of “pangolin” or “armadillo” since it appears to have scales and to be in a curled-up position.

The scales are not certain, however, since the bumps are pointing in the wrong direction, and they don’t really look like the plates of an armadillo. They might be scales (they do appear to overlap), or maybe it’s a VMS version of bumpy fur or wool.

The Wispy Tail

The tail is quite ambiguous. Are those untidy hair strands or is it a forked tail? In other VMS drawings, fish tails are quite detailed:

If the “pangolin” has a fish tail, why is it so tentative—why is it strandy instead of loopy? Is it intentionally vague? Or did the different context inspire the illustrator in another direction? Or is it a different kind of tail altogether, like a hairy tail? Maybe it’s vague because it’s an animal the illustrator has never seen.

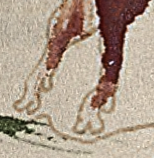

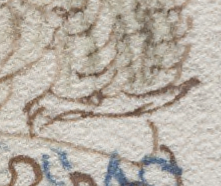

The Feet

The mystery animal’s feet look like cat’s paws without the claws showing. They look nothing like the feet of a pangolin or armadillo. But the VMS illustrator wasn’t exactly a rock star in the matter of drawing feet, as can be seen by the drawing on the right. These are the hooves of Taurus in the zodiac-figures section. Unlike most medieval drawings of hooves, they have soft edges.

This peculiarity is even more apparent in the feet of the dragon-like critter on the right. Instead of the fearsome eagle-like claws often seen on mythical animals, they are distinctly round, like those of the the mystery animal on f80v. Also, like the 80v animal, this critter has a long nose, long ears, a somewhat ambiguous tail (is it a medieval flower-tail? if so, why does it look like an extra paw?). It has some scaly stuff on its back (are they wings or a turtle shell?). Even though it somewhat resembles medieval dragon drawings, it’s hard to pin down the details.

The Head

The head of 80v, depending on how you interpret it, has a pointy upturned snout, possibly a round eye, and possibly a pointy horn or ear.

If it’s a horn, then it might be a reference to Jason and the golden fleece, something I’ve blogged about previously. Or maybe it refers to Aries.

If it’s an ear, then it seems to be one that’s long and pointy.

Other Possibilities

I try to look at the animal in as many different ways as possible (fur? hair? scales? leaves?).

Catoblepas?

Here is Pliny’s description of the catoblepas from Pelling’s site:

“…the source of the Nile… In its neighbourhood there is an animal called the Catoblepas, in other respects of moderate size and inactive with the rest of its limbs, only with a very heavy head which it carries with difficulty — it is always hanging down to the ground; otherwise it is deadly to the human race, as all who see its eyes expire immediately.”

When I read it, I thought to myself, that sounds like a warthog. The warthog roots along the ground with its head down, is somewhat hairy with a long mane that blows up when it runs. It has a very heavy head and is a very aggressive animal, dangerous to humans. In other descriptions, a mane like a horse is mentioned:

The rhinocerous also has a very large head and forages with its head down, but it doesn’t have a mane, and most of the descriptions of catoblepas fit better with warthogs.

The range of many African animals has greatly diminished. There used to be lions as far north as the Caucasus and giraffes in northern Africa, so it’s possible the warthog ranged farther north in medieval times than it does now. It is closely related to the wild boar and it’s possible their range originally overlapped. They are very similar in form, but the wild boar does not have the long distinctive mane of the warthog. This Roman mosaic shows a mane and also buffalo-like shoulders:

Here is another from the Bardo Museum with the mane and forelock standing up:

Warthogs are not especially known for smelly breath (it’s dangerous to get close to a warthog so it’s hard to get a whiff), but they do root around in poo, which might give them a reputation for smelly breath.

So I think there’s a fair possibility that catoblepas was inspired by the warthog. I noticed that Pliny does not mention scales, a feature that appears to have been added in later descriptions.

Other animals, like the wildebeest are also possible. In basic form it is similar to the warthog, with heavy shoulders and a mane, but it is much larger and has the snout of an ox. In proportion to its body, however, the head is not as big as a warthog’s.

Both warthogs and wildebeests are very aggressive animals…

I wonder if an animal as aggressive and smelly as the catoblepas would be portrayed as the mellow-looking creature in the VMS. Are there other possibilities a little more in keeping with nymphs and cloudbands and more pleasant topics?

The Amiable Aardvark

On the voynich.ninja forum, I’ve suggested the critter on 80v looks like an aardvark (they often curl up like a cat when they are sleeping). The problem is that aardvarks don’t have scales and the critter on 80v might. They do sometimes have fur up to about 4″ long, depending on the climate and variety (seven species of aardvark have been merged into one, so they no longer consider them separate species, but the length and color of their coats can vary widely):

The nose of the ardvaark is a good match for the VMS critter. It turns up at the end, like a pig’s snout, and is used to hoover up ants and termites:

When foraging, aardvarks always keep their noses to the ground and hunt by smell. For a long time it was thought that aardvarks and pangolins were related, perhaps because of their long tongues, and similar overall form and diet:

Could the VMS creature be a cross between an aardvark and a pangolin, cobbled together from a confused verbal report that describes ant-eating animals? There are many strange African animals in medieval bestiaries drawn from poorly understood verbal descriptions.

Part of the aardvark’s distribution is Ethiopia, a pilgrimage site sometimes included on medieval maps with a little line of European castle icons. The aardvark is a more amiable creature than the warthog—it is sometimes kept as a pet.

Back to the Beaver

In a 2016 blog, I suggested the critter might be a beaver, the animal most often depicted in herbal manuscripts and bestiaries as the unwilling donor of castorum, a substance in testicles that was thought to have medicinal value. Beavers were often drawn with scales, long ears, and long snouts, as in this example from the previous blog:

It was the curled-up position and scales that made me wonder if it might be the castorum beaver, since it is usually drawn with its nose in its groin, biting off its testicles. A cloudband might also be relevant since the beaver is making a choice between death or life without progeny.

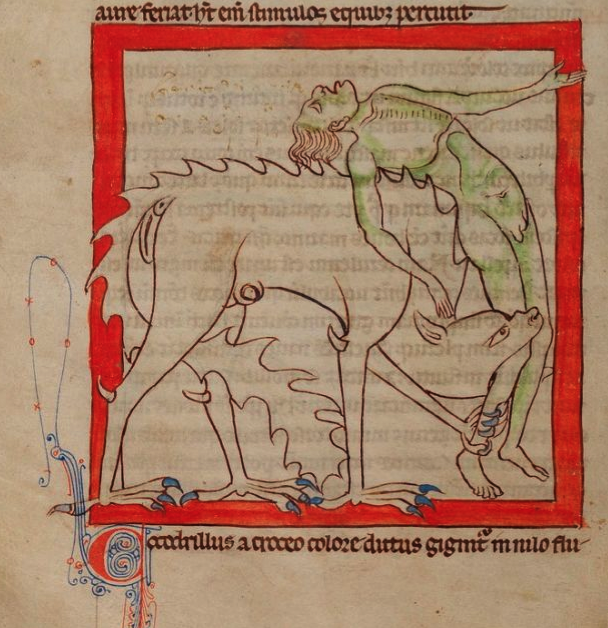

Reptilian Possibilities

I wanted to include these enigmatic drawings because they show how far medieval drawings can diverge from nature. This furry doglike creature with chicken legs is from the Northumberland bestiary (c. mid-13th century):

And this c. 1315 creature has long ears, a wavy mane, fluffy tail and doesn’t look reptilian at all (BL Royal 2 B VII):

It may be hard to believe, but both of them are crocodiles. However, a crocodile is not really designed to tuck its head under its body.

The Folio as a Whole

What else is going on on the folio? Critter 80v is sandwiched between hovering nymphs holding a spindle and a ring. And, oddly, the critter is lightly dabbed with streaks of green, a color associated more with reptiles than mammals.

In the green pool at the base of the folio is a nymph that started out with no breasts and has an unusually shaped pair of “eyeball” breasts quite different from the other nymphs (they look like they were added by a different hand).

There’s a lot going on on the right-hand side, too much to cover in this blog. K. Gheuens has suggested an interesting possibility—a connection with constellations. That’s a provocative idea and a topic in itself, so I’ll leave it to the reader to consider his interpretation while I get back to the critter…

What about the scalloped shape under the critter?

Is that a cloudband? Do the vertical lines represent rain?

Is it water, do the scallops represent waves?

There is certainly the hint of a cloudband in the middle-right rotum on the VMS “map” folio. But similar shapes also appear to resemble fabric.

On folio 79v, which is stylistically similar to 80v, the scalloped shape looks like an umbrella or tent-top with a finial. I don’t think we can assume every wavy shape is a cloudband.

If it’s fabric, maybe critter 80v is curled up on a cushion—a squarish cushion with a scalloped trim. Is this some nobleperson’s pet taking a nap?

The idea of a pet aardvark or catoblepas doesn’t quite fit the context of hovering nymphs with attributes. The nymph above the critter sits in something resembling a double cloudband, at an elevated position on the folio, all of which makes her seem somewhat important. The one below holds out a ring… which brings me back to the idea of Agnus Dei (the lamb of God) that I suggested in a previous blog.

Agnus Dei

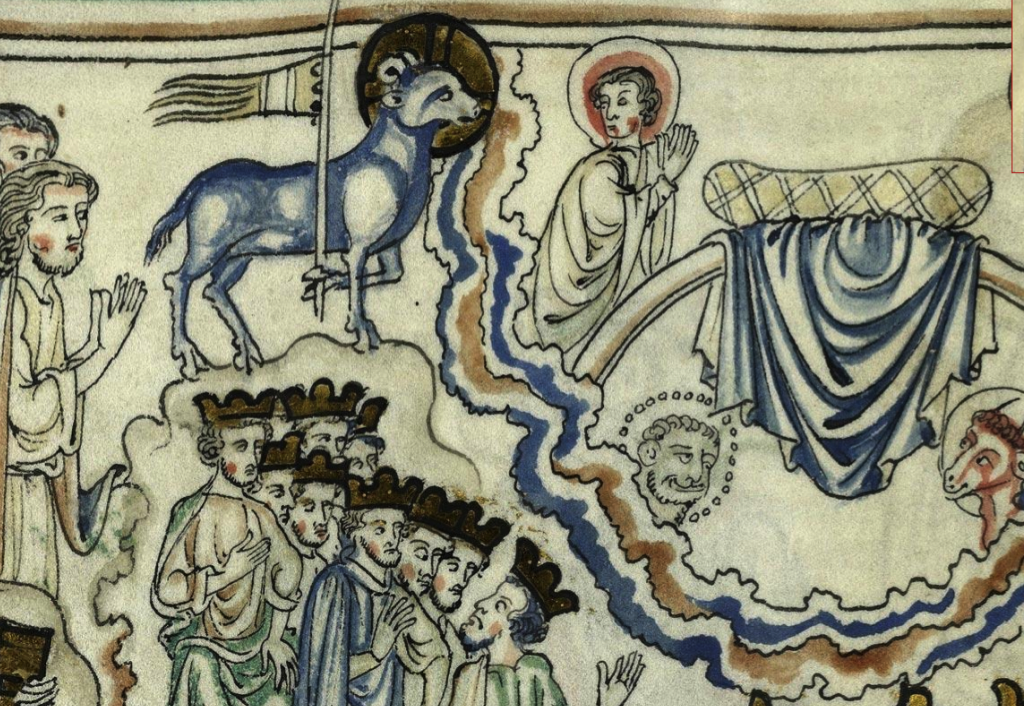

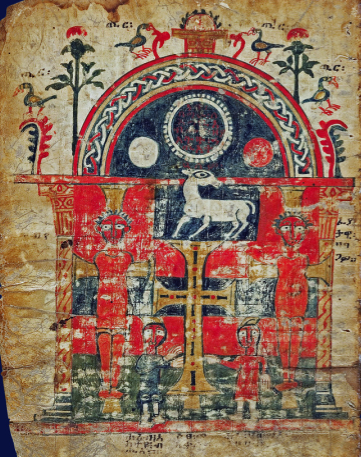

The lamb of God is associated with ascension and redemption, based on biblical passages. Much of the time, Agnus Dei is represented like this, standing in a prominent position, with a cross-staff and banner, often nimbed:

Here is another from British Library Additional 17333, with the lamb standing on an altar:

The lamb is often surrounded by a wreath or a rainbow, or decorative elements that one sees in church alcoves.

In almost all instances, the lamb is on some kind of pedestal or cloudband, or perched on the top of a crucifix. Frequently it is positioned midpoint on the page or fresco, between earthly matters and God:

In a 6th century mosaic in the Basilica of Santi Cosma e Damiano, the lamb is standing on a base with water flowing out below its feet. Pagan influences are still present in this very early depiction:

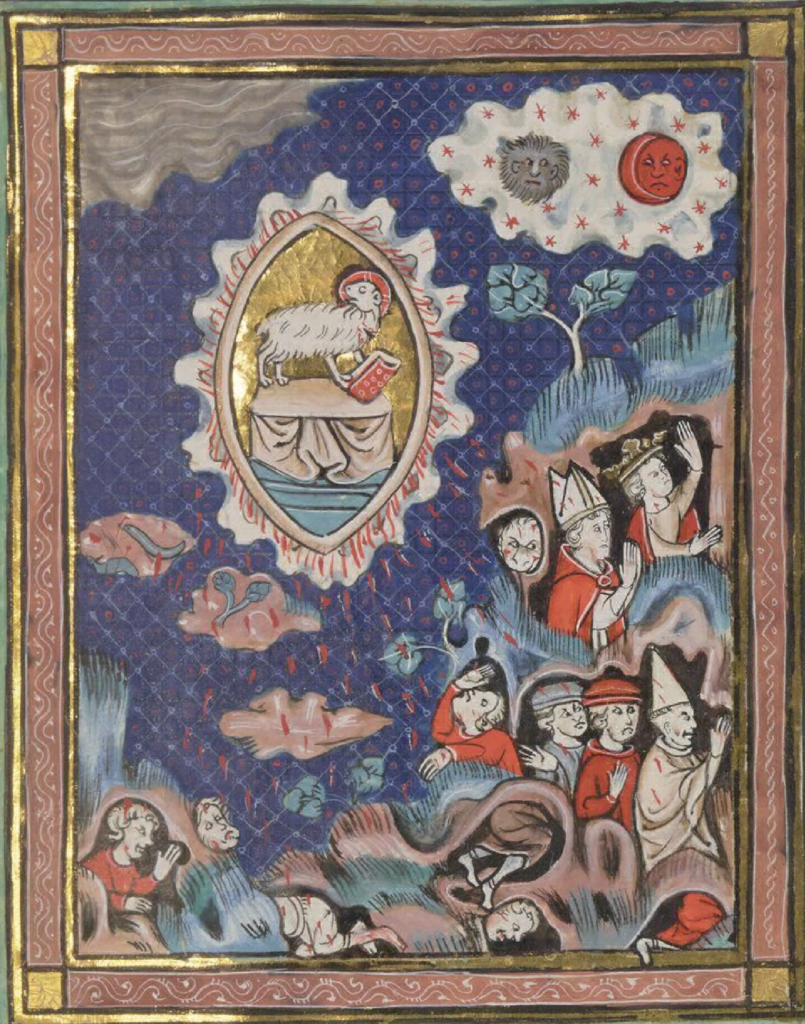

Toward the Middle Ages, it became popular to add a scroll or book with seven seals dangling from the base:

Another popular medieval theme was setting the lamb on a cushion, cloudband, or book with seven seals dangling from the edge, as in this early 14th-century example in the Martini church in Braunschweig, Germany:

This 19th-century interpretation retains the traditional cross-staff, book, and seven seals, and places the book with the seals on a cloud-cushion:

Could the lines under the VMS “cushion” be rain? Or does it represent movement (ascension?), or possibly an abstract reference to the seven seals?

In this c. 1260 drawing, the lamb stands on a cloudlike line above the heads of watchers, facing an empty cushion, a place for it in heaven ringed by a double-layered cloudband:

The Sacrificial Lamb

This version has blood pouring from the chest of the lamb, a detail that might be relevant to the VMS…

The lamb was used for sacrifices and one of those sacrifices occurred after a woman had given birth. There are many hints at ob/gyn themes in the VMS and perhaps this is another one. Below the 80v animal we see a ring, often representing marriage, then we have the lamb, used as a sacrifice following childbirth, above it a woman with a spindle—spinning was an activity that many women took up when the children were grown and their nest was empty. Is there a life-story narrative here?

Notice also, in the St. Antonius example, that the texture of the fur has been drawn as scales.

Notice also that a turned head is very typical for lamb-of-God imagery.

The lamb doesn’t always look like a lamb. Depending on the skill of the illustrator, sometimes it looks like a kangaroo with its head down:

Sometimes the lamb looks vaguely like the VMS drawing of Aries, drawn within a circle, with a leg held high:

This example has a couple of things in common with the VMS: the drawing is not professional level and the “pedestal” is hard to identify. Is it water or a cloudband? Given its early date, it’s probably water:

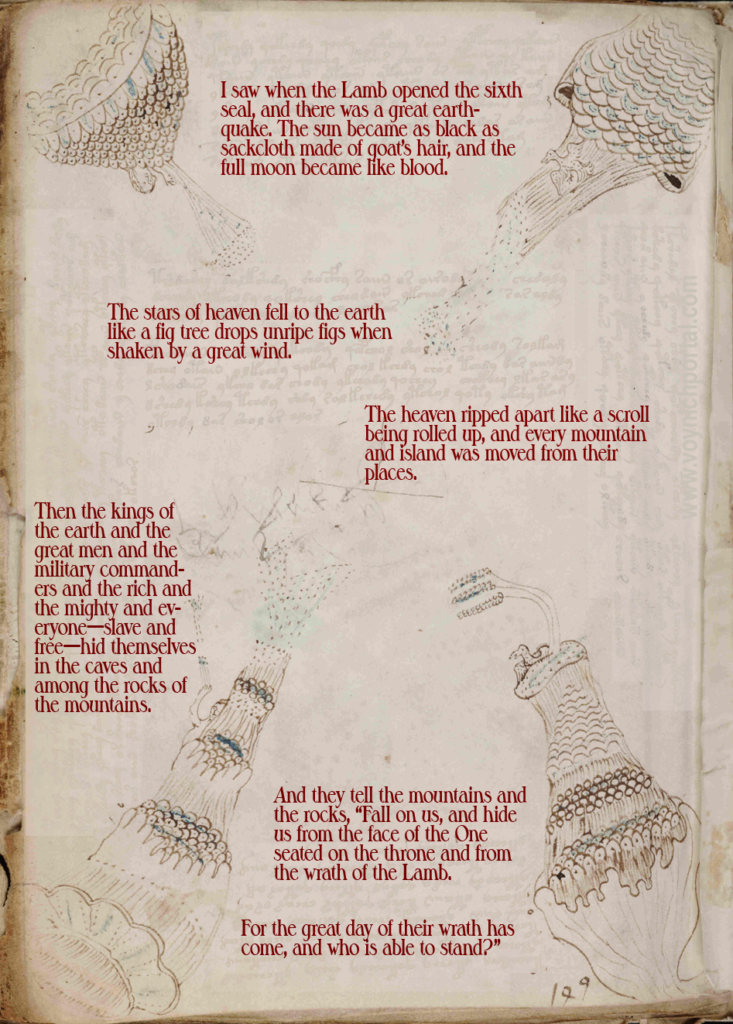

This example is interesting because it combines Agnus Dei on a fabric platform with imagery that is similar to VMS 86v, and also represents an early example of a sun and moon with faces:

Here is one possible interpretation of 86v that I posted in a previous blog:

Could the 80v animal be somehow connected to the imagery on this folio, as well?

Is it possible that the object and wavy lines under the animal represent water, clouds, and cloth all at the same time, and thus encompass all the popular ways of representing it?

Could the nymph holding the ring under the animal represent a marriage scene, as in some of the English apocalypse manuscripts from the 13th century?

As an aside, I thought I’d share this little gem I stumbled across in an early medieval manuscript. The scribe has turned a flaw in a piece of parchment into a “holy” lamb.

Summary

I have tried hard to find an explanation for the animal on 80v that fits as many aspects of the folio as possible. I suggested the idea of Agnus Dei in a previous blog, but the blog was already too long to add all the pictures, so consider this a continuation.

I rather like the idea of an aardvark on a nobleman’s pillow, or the infamous life-or-death castorum beaver, but the folio does not look like a bestiary—the relationship of the images to one another has a more narrative feel. I wanted to explain the relationship of the lamb to the other figures and to the various props in the margins and, hopefully, to some of the other VMS folios.

The idea of Agnus Dei seems more cohesive than the other possibilities and the fact that the animal appears to have scales is apparently not a problem, since the St. Antonious lamb does, as well.

Many medieval drawings are ambiguous, it may turn out to be something completely different, but at least this idea relates to some of the other elements in the VMS.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2019, All Rights Reserved

Interesting, I had never noticed those wedding scenes before.

One problem I have with Agnus Dei specifically is the general lack of Christian symbolism in the MS. It would be strange to get a full-blown Jesus-as-lamb here, I just don’t buy it. There’s also no wedding between the (apparently rather upset) ring-holding woman and anyone else. She does point the ring to the other side of the page.

I’ve always been sceptical about the possibility of it being a lamb or sheep, but you do make some good points nonetheless and I may have to reconsider.

One thing we must keep in mind is that pesky VM visual polyphony. It could be a sheep because of the two toes on the front paw, but it can’t be because of the three toes on the back. And even bad artists would most definitely have known the proper amount. So this is likely intentionally ambiguous.

And those scales. They look like scales. But they are drawn the other way around, leaving room for them being something else. Like, I guess, wool.

What I find more likely than Agnus Dei is the sacrifice of a lamb after childbirth as described in Leviticus. It would explain the lifeless appearance of the thing, as well as perhaps its being placed above some kind of basin.

The VMS has never struck me as Christian either. It has always felt rather pagan to me, although I’ve always looked for Jewish influences since I first saw the text on 116v (I wondered whether the German parts might be Yiddish) and also because many translators and scribes were Jewish.

I was keenly aware when I was writing this that references to Revelation and Agnus Dei are New Testament stories, undeniably Christian in origin. But I wanted to put those ideas aside and simply try to describe what I saw in terms of similar iconography in medieval literature and so far, the best explanations I can find for the various elements on the folio combined with a critter on something like a cloud-pillow are: the castorum beaver, a conflation of the pangolin with an aardvark, a golden fleece, a sacrificial lamb on its way to heaven, or Agnus Dei.

If I can come up with something better, I’ll certainly post it, but this is what I have so far. 🙂

P.S., I had intended to include a quote about the sacrifical lamb from the Old Testament, but while hunting for it I got sidetracked… and forgot. Plus, even now, I can’t think of a short way to include it, there’s so much history to sacrificial lamb rites that the subject requires a full blog.

Looking back through this, I hope people don’t think I’m rejecting other ideas about the critter on f80v. At this point I think almost anything is possible, including animals suggested by others. But these are the ones that specifically came to my mind that I thought might be relevant and which appeared to have at least some relationship to other elements on the folio.

There is no “label” next to the critter, but that may not matter, since “labels” don’t appear to be particularly enlightening at this point. We’ll just have to figure out the main text. 🙂

Sounds to me like the catoblepas is an African Buffalo.

Interesting speculation, but some of the Roman images appear to be boars, not warthogs.

In the discussion of the first image in ‘Reptilian possibilities’, you say it “doesn’t look reptilian at all”, but look at the feet. Are they bird / dragon feet?

So many interpretations to consider, but still no mention that a line with bulbous crests and troughs fits the heraldic definition of a nebuly / gewolkt line. And both of these terms through their etymological origins imply a cloud-based interpretation. As a first approximation, perhaps the separate interpretations of the critter and the “wobbly” line structure should work together.

I used to think the nebuly line meant clouds but i an starting to think it denotes shoreline, as it does in such maps as the Tabula Peutingeriana. I think it is there to show the location and shape of the Alps in that region. That it turns a corner implies to me the location of the bay in which Marseilles is found, and the Rhone delta. This fits well with the hindleg being situated near Monaco. If you look at Portolan maps of the time, or even long after, the Alps might have green or brown scales but are not shaped correctly, more like a boomerang standing on end, and many are placed too far east and/or north, or sometimes are replaced by a painting of Genoa harbour, which also resembles the creature somewhat in shape. If you compare the creature with an elevation of the Alps, many features seem to correspond very well, such as backfacing scales, squared scales, double eye, and other small features that can’t really be explained by other means.. This logo features an elevation that suits such a comparison, just remove the Austrian part of the Alps, the dark part on the top right.

https://homoalpinus.com/img/graph/capleymar_alps.png

On closer examination, I think you’ve got it. Look at the example image you posted that is fourth from the end. The lamb is in the vesica piscis, which is a cloud-band, and beneath it are scattered red markings, apparently intended to represent drops of blood.

This shares a similar construction as the VMs illustration. The same three parts are in the same relationship.

1. Lamb, VMs critter; 2. cloud-band, nebuly line; 3. blood of the lamb, ambiguous precipitate

It’s about the parts *AND* their relationship in combination.

Leave it to the VMs to be ambiguous. Is it rain or is it blood? Without the use of color, who can say? It almost constitutes a modus operandi: illustrations that correspond in their construction, but contrast in visual appearance.

Interesting. I am interested in the presence of the birds on 86v in a Christian context as well. There are currently two other MSs which I feel excited about in relation to the VMS, and both of them are Christian. One, however, features an image of what seems to be a bird—with a halo?—anointing Jesus at his baptism (or something along those lines). Here is a link to that image https://tinyurl.com/y4c8h6vm if you’re interested. The context for the second MS bird illustration is less clear to me, but its similarities to VMS illustrations strikes me and it is in an Italian translation of Nicholas of Lyra’s Apocalypse commentary. I am probably biased because I have always felt like the VMS had the feel of a Christian text, potentially produced “on the side” or “underground” by individuals who could have been members of a more traditional religious order, like the Franciscans for example, but who secretly held heretical views. That is very speculative of course, but just want to acknowledge my bias! You can see the second bird image here https://tinyurl.com/y5w8rd96 if you’re interested.

Although I am sure you will have seen them before, JKP. You have an astounding breadth and depth of knowledge. Thanks for taking the time to share your insights and observations with the rest of us.