Introduction

I have a particular reason for uploading this information ahead many of the other Voynich-plant articles that are sitting on my hard-drive. I have not spent extensive time looking at other Voynich sites (very little actually) but it’s impossible to look up pictures of plants without Edith Sherwood’s name showing up in the search. Her plant pages have been online for many years and thus have filtered into the blogosphere to the point where it’s almost impossible to not see them and many of the identifications, like this one, take me by surprise.

Sherwood has identified Voynich Folio 30v as a plant named dodder.

First let me make it clear that I am not a botanist. I like plants but have no time to garden or to study the correct technical terms for their parts. I understand that the colored part of a plant that looks like petals is not always a petal, it’s sometimes an extended bract or calyx, sometimes it’s a colored leaf, but that’s as far as my botanical knowledge goes. Nevertheless, despite this lack of background or training in botany, I think I can say, with considerable confidence, that this plant is not dodder. First I’ll describe the Voynich drawing and then I’ll explain my reasons for rejecting Sherwood’s identification.

Description

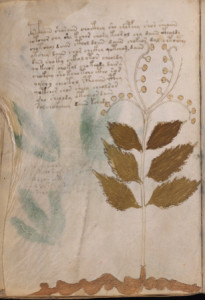

Folio 30v features a plant that covers most of the page from bottom to top. It has an erect stem that is left unpainted except for the part that connects to the roots. Along the stem are three sets of opposite elliptical leaves. The leaves are distinctly serrated, perhaps even toothed, and have been colored a greenish-brown. Unlike many of the VM plants, the veins have not been included, so it’s impossible to know if they are parallel or, more commonly, have veinlets that extend out from a central vein.

Folio 30v features a plant that covers most of the page from bottom to top. It has an erect stem that is left unpainted except for the part that connects to the roots. Along the stem are three sets of opposite elliptical leaves. The leaves are distinctly serrated, perhaps even toothed, and have been colored a greenish-brown. Unlike many of the VM plants, the veins have not been included, so it’s impossible to know if they are parallel or, more commonly, have veinlets that extend out from a central vein.

Above the leaves, the stem branches into four curving stalks that have evenly-spaced berry-like structures with a dot in the middle. The very tips of the upper stalks include a curved leaf-like endpoint that extends past the last “berry.”

The upper part of the stalk is embellished with long delicate lines that resemble hairs and between the pairs of “berry” stalks on each side is a feathery extension with asymmetric “hairs.” Whether these are left-over branches from a previous year (or a previous blooming in the same year), a differentiated structure, or something else, is not clear from the drawing.

The roots are distinctive— long wiggly rhizomes extending off the page on both sides. They are painted a brown color but not quite the same greenish-brown as the leaves.

The text occupies three lines across the top and wraps along the lefthand side of the plant for another eight lines, brushing the edge of the plant in four spots.

Prior Identifications

As mentioned, Sherwood claims this VM drawing represents Cuscuta europeaea, known as dodder. Dodder is a common plant growing in many parts of the world. I’ve seen it on some of my hikes, without knowing its name.

The first time I noticed dodder, many years ago, the twining string-like stem had a vertical strangle-hold on a pair of wetland plants growing by a slow-moving creek. Slender tendrils snaked around the tangle of stems, binding the two plants together in a lover’s knot, with intermittent puffs of pale flower clusters serving as the nuptial bouquets.

As sinister as it was lovely, the twining dodder had no leaves of its own, preferring to parasitize the plants it so tightly binds together.

The picture on the left, which I added the day I uploaded this blog, shows the twining tendrils, courtesy of Wikipedia, and I discovered from the wiki that dodder goes by names such as hellbine, devil’s guts, strangleweed, and witch’s hair and that it does, in fact, have leaves, but the vestigial structures are little more than tiny scales. Without significant leaves or chlorophyl, it cannot draw energy from the sun in the same way as other plants and makes up for this by pushing sharp little “suckers” into the host plants to vampirize their nutrients.

So why would Sherwood identify the Voynich plant as dodder? As far as I can see, they have nothing in common. Dodder is a virtually leafless vine with intermittent flower clusters and, once it insinuates its suckers into another plant, it sheds its roots. In contrast, the VM plant is an erect plant topped with long rows of berry-like structures, with showy, serrated, elliptical leaves, and burly, long roots. As far as I can see, dodder and the VM plant have nothing in common.

So putting aside the obvious misidentification, is it possible to provide a better ID for VM 30v than given by Sherwood?

Possible Identifications

Poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), a plant well-known in North America, has serrated elliptical leaves, substantial roots, and long stalks with white berries that have a dot in the center like VM 30v. When heavy with berries, the stalks droop and curve like the VM plant, but they tend to cluster at the nodes rather than extending from the apex of the plant. The leaves, unlike the Voynich plant, are trifoliate.

Another plant that closely resembles the “berry” stalks of VM 30v is poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix). It has long spindly stems holding round white berries with a small black dot in the center. They are not expressly one-sided on the stem as in the Voynich plant, but they do sometimes have more berries on one side than the other. The sumac has elliptical leaves but they are not distinctly serrated and they are trifoliate at the ends of the branches. The “berries” are a good match, but the rest of the plant is less so.

Baneberry (Actaea) also resembles VM 30v in that it has long stocks with red or white berries with a black dot in the middle, serrated elliptical leaves and, in the case of red baneberry, hairs along the stems under the berries. Like Poison ivy and poison sumac (and unlike VM 30v), Actaea leaves have a trifoliate or odd-pinnate arrangement, depending on the species.

Perhaps a better candidate for VM 30v is dog’s mercury (Mercurialis perennis), a European plant with elliptical serrated leaves, substantial roots, and numerous tall spindly stalks studded with berry-like green seed-heads. The roots are somewhat thick and numerous and do have long rhizomes extending out to the sides. What is especially interesting about Mercurialis is that if you flatten it into a herbarium specimen, it more closely resembles the VM plant and, when it blooms, has hair-like stamens that are perhaps represented by the delicate structures between the stalks. It’s also possible the more delicate stalks represent the male plant, with the berries representing the female. A less common species, Mercurialis ambigua, has both male and female structures on the same plant.

Where Mercurialis differs significantly from VM drawing is in the shape of the fruits. The VM “berries” are distinctly round with a central dot, whereas dog’s mercury is somewhat triangular and arranged in clumps. Even the closely related Mercurialis annua (which has rounder “berries”) forms clumps rather than discrete berries that are covered with hair-like protrusions. The VM “berries” are smooth.

There’s one more plant that might be considered. Like Mercurialis, it’s not a perfect match, but it does have some interesting similarities.

There’s one more plant that might be considered. Like Mercurialis, it’s not a perfect match, but it does have some interesting similarities.

VM 30v has leaves that are very distinctly opposite and Circaea lutetiana (enchanter’s nightshade) has this characteristic, as well. The base of C. lutetiana‘s leaves are slightly more rounded than the VM plant, and it doesn’t generally have such deep serrations, but it does have branched fruiting stems that often branch in groups of three, but typically vary from two to four.

There are numerous roundish fruiting bodies along each top-stem and the ones near the base tend to be more asymmetric than the ones near the top. Where they differ from the VM plant is in their shape, which is more teardropped, and they don’t have a distinctive dot at the end of each “fruit”. I suppose the round shape might not be a fruit at all—if it were the bud before the flower opens, there is a small light spot at the end of each one, but the shape of the bud is more oval than round. Also, assuming the VM plant is drawn somewhat to scale, C. lutetiana‘s seedheads are not as large as VM 30v, relative to the stem. Another significant difference is that C. lutetiana‘s fruits are quite woolly, whereas the VM 30v drawing doesn’t have this characteristic, except on the stem. Was the VM illlustrator trying to express the hairy aspect of a plant without putting in each hair? The roots of C. lutetiana somewhat resemble the VM plant but lean more toward being a tap root.

If you were to take dog’s mercury and enchanter’s nightshade and merge them, you might get something similar to VM 30v but neither one, by itself, completely fits the bill, which means there may be a plant that resembles it more closely or the features of the plant are drawn less accurately than one would hope.

The alternatives mentioned here may not entirely match VM 30v but I think it can be said without hesitation that the VM drawing does not, in any way, resemble dodder.

Posted by J.K. Petersen