C-3PO, of Star Wars fame, knows more than 6 million forms of communication, so maybe he can read Voynichese. Unfortunately, he’s signing autographs on distant planets, so I had to solve this puzzle for myself. Even if you can’t read abbreviated medieval script, you will probably notice this folio includes encoded data.

The following sample is from a 15th century text that deals mainly with astrology but I could see that the subject matter had changed (or, at least, the focus had changed) when I reached folios 160 to 169. I looked around the Web to make sure no one else had already posted about this section and couldn’t find anything, so here it is…

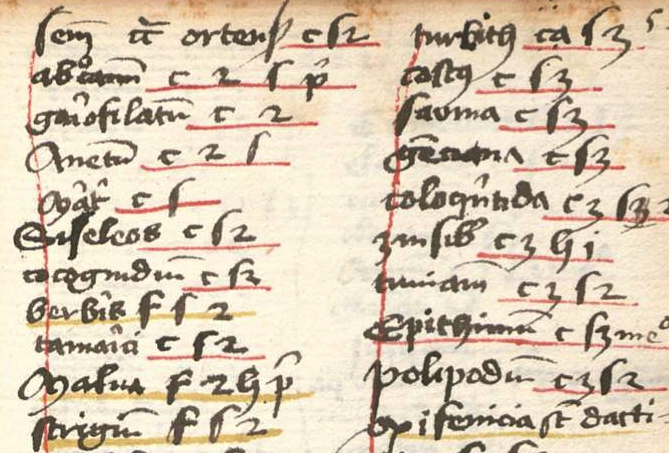

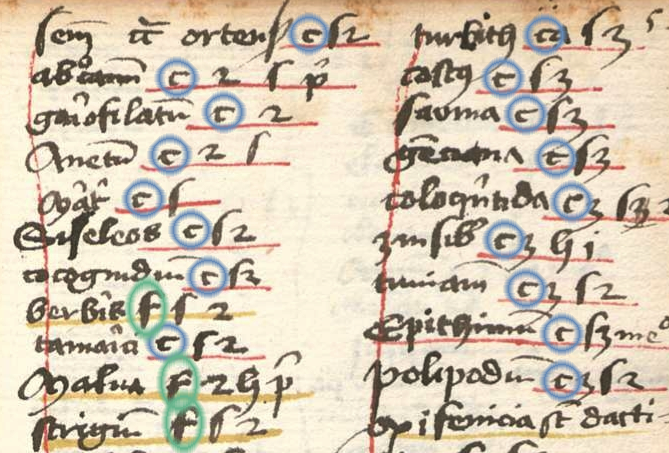

Each folio has two columns. Each column has text on the left and cryptic letters and numbers on the right. This manuscript (BSB CLM 667) is from the late 15th century, but I have seen diagrams in other manuscripts from the mid-15th century that represent information in somewhat similar ways.

As I glanced through it, I noticed these are lists of plant names written with common Latin abbreviations, including abrotanum, gariofilatum, anetum, berberis, tamarisci, malva, strignos, turbitus, costus, epithimum, polipodium, and others. The spelling is slightly unconventional, but the names are consistent with plant names in medicinal herbals.

So what is the encoded information next to the plant name?

I was intrigued because I’ve long suspected that at least some Voynichese might be expressed in novel ways. In fact, I’m hoping it is because it would be more satisfying to discover that it’s a terse code rather than nonsense text. So, several years ago, I labored for almost a year to create a color-coded “concordance” of every token in the VMS, looking for patterns that

- might be specific to certain sections of the manuscript,

- might link separate sections, or

- might recur on certain locations on each plant or other section-specific page. If such patterns could be identified, it might be possible to zero in on sections of codified information that occur on more than one page.

But back to analyzing the text to the right side of each column…

Years of looking at ancient and medieval herbals helped me puzzle out the CLM 667 text in a few seconds because the plant names gave me the context I needed to interpret the rest (I wish the VMS were as cooperative, but then I guess there would be no mystery to solve).

This is how it works…

You’ll notice in Clm 667 that the first glyph in each column is a letter, and is sometimes followed by a number or another letter.

Note that each sequence begins with c or f. That instantly reminded me of Latin calidus and frigidus, properties or “temperaments” that the ancient Greeks associated with each kind of plant.

In ancient medicine, they believed that plants should be chosen to balance their properties against those of the illness. For example, if you had a fever (were hot and sweaty) then plants that were “cold” and “dry” might be suitable for “balancing” your humors. Thus, they felt it important to assign and record these properties.

So, guessing that the first letter represented hot or cold gave me clues to the rest of the sequence. If there was a number after the c or f, it indicated the degree to which this plant embodied the stated property. For example c 2 would represent calidus (hot) in the 2nd degree or f p’ (notice the cap, which is a Latin abbreviation symbol) would mean frigidus (cold) in the 1st degree, with p’ (which can also be abbreviated as p’° or p°) representing primo gradu .

I noted that if the next character was a letter rather than a number, it was always s or h. That confirmed my hunch about c and f. Plants are categorized as hot or cold and dry or wet. In Latin, dry is siccus and wet is humidus. So, if the annotation is f s 2, it stands for frigidus et siccus in secondo gradu.

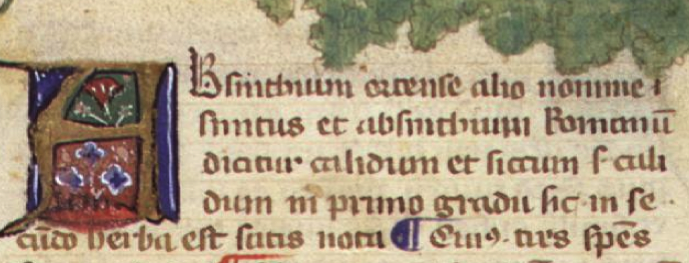

In contrast, here is a more traditional example for absinthium in an herbal manuscript (Historia Plantarum), created c. 1400, in which the plant is described as calidum et siccum (hot and dry), followed by additional information that it is hot in the first degree and dry in the second. The verbose entry requires 49 characters (including the macron but not including the spaces):

In contrast, the writer of Clm 667 created a simple system for classifying properties of plants that can be expressed with four characters or less.

Now imagine if the lists in Clm 667 were converted to a cipher system. Like the VMS, the text would be extremely repetitious, and it would be very difficult to discern what kind of information was in the “properties” text (especially if the spaces were removed or represented by null characters). Also, like the VMS, the glyph positions would be more regimented than narrative text—certain glyphs would occur more often at the beginning, some more often at the end.

Summary

There are several reasons for posting this example…

- It illustrates medieval evolution in representing information,

- it provides a 15th-century example of codified plant data that is outside the mainstream (not everything was slavishly copied in the Middle Ages),

- it demonstrates that VMS labels shouldn’t be assumed to be nouns (I’ve noticed this is a very widespread assumption among Voynich researchers)—they may be abbreviated or encoded character traits (easy to say, but this example demonstrates how it might be done),

- it expressly demonstrates that VMS text should not be assumed to be wholly linguistic. The text may be abbreviated in a number of ways… the VMS could include scribal abbreviations that are linguistic or symbolic, or an entirely different system of coding,

- if there is codified data that includes numbers, then the majority of Voynich “solutions” are inadequate even if they turn out to be partially right—very few researchers include numbers in their proposed solutions, even though numbers are commonly found in medieval manuscripts, and

- it provides an example of a system that might account for glyph-priority within tokens.

The idea that the VMS might be ultra-abbreviated is not new—the possibility has been mentioned by others. Highly verbose codes have also been suggested—neither contention has yet been demonstrated or proved.

I’ve been investigating the possibility of codified text for almost as long as I’ve known about the VMS because I’m familiar with data encoding in scientific papers and noticed many of the VMS tokens were quite short and formulaic, but finding a medieval example to confirm that this kind of thinking existed in the 15th century can be difficult if you are explicitly searching for it. Sometimes it’s better to wait until a suitable example comes along, as happened with Clm 667.

J.K. Petersen

© 2018 J.K. Petersn, All Rights Reserved