I’ve frequently posted that Latin scribal conventions are flexible. They are like Lego® blocks that can be taken apart and recombined in many ways. This is essential to understanding Voynich text. Looking for similar shapes is not enough, one has to consider the combinatorial and positional dynamics of medieval text in relation to the VMS.

Basic Building Blocks

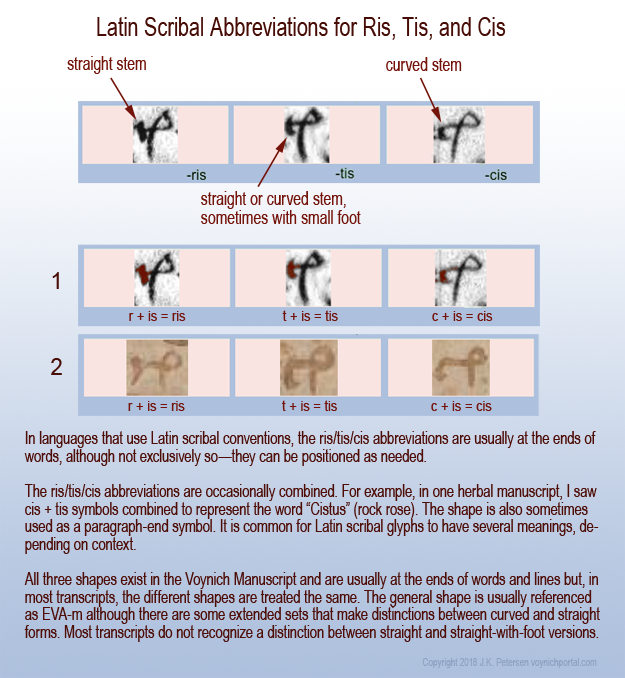

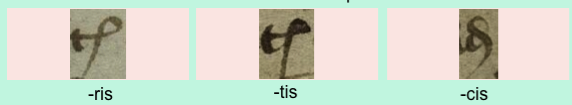

I’ve already discussed these shapes in previous blogs, but I’m going to post again with additional examples. This is one of the most common Latin scribal conventions, frequently used to represent the syllables “ris”, “tis”, and “cis”.

The glyphs below are from two scribes with different handwriting styles so you can see how the abbreviations vary from hand to hand, but can still be understood by the reader:

Some parts of the ris/tis/cis abbreviation are meaningful and some can be changed to suit the person’s handwriting or aesthetic sensibilities. This is one of the reasons why it’s important for the dynamics of scribal abbreviations to be understood—meaningful and non-meaningful variations in glyph-shapes need to be differentiated to create accurate VMS transcripts.

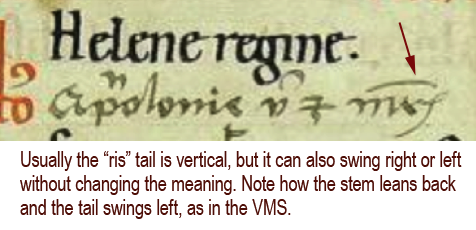

For ris/tis/cis, the left side of the glyph defines the meaning (although ris and tis can sometimes be hard to tell apart in 15th-century documents and tis and cis can be hard to tell apart in 13th-century documents). In the example below, it’s quite clear that the left side is “r” for ris, but the shape of the right side can be varied, as long as there is a small loop with some kind of tail. In this 15th-century addition to an early medieval calendar, the tail is long and swings left:

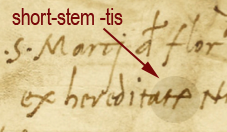

A further example (c. 16th century), shows that the ris/tis/cis abbreviations were still used during the Renaissance and early modern period, and could vary in shape, as long as the meaning was clear from the context. Note here that “tis” looks like a small EVA-k at the end of the word hereditatis. It has a straight stem (no foot as in earlier script styles) and a short tail, and yet is perfectly understandable:

A further example (c. 16th century), shows that the ris/tis/cis abbreviations were still used during the Renaissance and early modern period, and could vary in shape, as long as the meaning was clear from the context. Note here that “tis” looks like a small EVA-k at the end of the word hereditatis. It has a straight stem (no foot as in earlier script styles) and a short tail, and yet is perfectly understandable:

Here’s an example in a different 15th-century hand in which ris has a foot and so, to distinguish it from tis, the scribe has given tis a bigger foot and a subtly more rounded back. Also notice how cis is rounded to the point that it looks like EVA-d with a tail. This cis-variation is also found in the VMS and might be a hand-variant of the cis-shaped glyph or might be a separate glyph:

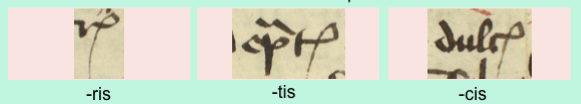

This example, from yet another 15th-century scribe, shows tis and cis in context. Even if you don’t know medieval Latin, you can probably figure out that the word on the right is “dulcis”. Note how the tis and cis are at the ends of the words. This is how they are usually positioned in languages that use Latin conventions and in the VMS, but they can be placed elsewhere if desired:

Similar Shapes in the VMS

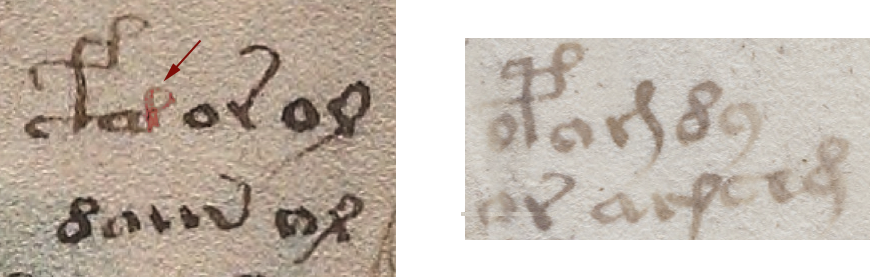

Now I’d like to point out a snippet from the VMS that suggests the Latin “is” convention was probably known to the scribe or designer, because it is not always written like EVA-k and EVA-m in the VMS. A right-facing loop with a stem is sometimes attached to other letters.

On the left, an “is” shape has been attached to EVA-a or, alternately, it might be a straight-leg EVA-d attached to the right side of a bench. Either way, EVA-d has a variant form with a straight leg that is similar to Latin short-leg cis. I don’t have a clip handy, but “is” also appears next to other glyphs such as EVA-y.

In the example below-right, both ris and cis shapes are visible, but what you might overlook if you are not familiar with Latin scribal variations, is that the character in the middle of the second line is drawn a little differently. This might be a differently-written ris (different from others in the VMS), OR if one were reading this as a Latin scribal glyph, it could also be interpreted as EVA-i with the looped shape added:

Summary

Summary

After I wrote a series of blogs on Latin scribal conventions there was a mini-flood of Voynich “solutions” that made the headlines, all claiming that the VMS was abbreviated Latin. They looked suspicious to me because the researchers clearly didn’t understand how to use these conventions correctly and thus could not have come up with the idea independently.

Here are some of the major problems with these “solutions”:

- Latin scribal abbreviations don’t automatically mean Latin language. Latin conventions were used in all major European languages. Even some of the west Asian languages apply some of the same concepts. The VMS might turn out to be Latin, but not in the simplistic way these researchers translated the VMS text. And it might not be Latin—the same scribal conventions are used in Spanish, French, English, German, Czech, Italian, and other languages. Sometimes the same shape means the same thing in different languages, and sometimes it is adjusted to fit the spelling or grammar of the host language (for example, a squiggle-apostrophe might mean -er in English and -re in French).

- Most of the proposed “solutions” are nonsense words, not Latin. They might include one correct Latin word out of every 20 or 30 words (more by accident than by design) and they might look a bit like Latin, but it’s not Latin vocabulary, it is certainly not Latin word-order or word-frequency, and it definitely isn’t Latin grammar (not even note-form grammar).

- Those offering the solutions expanded the abbreviations incorrectly—that was the give-away that they hadn’t really done their homework and probably got the idea from somewhere else. Saying that it’s Latin is easy, anyone can do it—demonstrating that it’s Latin when you don’t know scribal conventions makes it really obvious to those who can read medieval script that the person offering the solution is not even superficially familiar with the basics. One of the solutions, published in a prominent newspaper, expanded one of the most simple and common Latin abbreviations the wrong way (he forgot to take into consideration the position of the abbreviation in the word). Another solution didn’t recognize the fact that Latin scribal glyphs have many different meanings, not just one, and that the meaning is inferred from context. The solver expanded them all the same way which, once again, generates nonsense rather than natural language.

The VMS might be natural language and it might not. If it is natural language, it’s possible scribal shapes are different from alphabetical shapes. The majority of computational attacks do not take this into consideration, or the fact that if there are scribal shapes, they might need to be expanded.

So, I will continue to post examples, as I have time. Perhaps a better familiarity with medieval conventions will help researchers understand which glyphs might be combination glyphs, which parts might need to be expanded (if the glyphs do, in fact, represent abbreviations and ligatures), and how VMS transcripts could best be adjusted to provide a more accurate rendering of the text.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2018 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

I’ve actually learned something from this post, now I must try to remember it 🙂

On some pages there seem to be an abundance of both -ris and -tis examples. Do you think it could be informative to map these over some pages and run some tests on them? I’m not sure which tests, but there must be people who can think of something.

Sorry, Koen, somehow I missed your comment when you first posted it. I’m seeing it for the first time today.

Yes, I think it would be informative to map and compare them to blocks of medieval text in terms of where they are positioned. The problem is that most Latin translations expand the abbreviations and there are not many conventions for recording them in their original form. Also, this convention is used in several languages (which has to be considered as well), so preliminary work would be necessary in order to run statistical tests.

From a subjective point of view, in languages that use Latin scribal conventions, the pattern is common. The -ris symbol, in particular, is usually found word-final, and sometimes also line-final and paragraph-final. It has a few common meanings (although most of the time it stands for -ris).