where can i buy Lyrica in australia The Vessels in the “Kitchen Section”

When I first saw them, the vessels on the left-hand side of the plants in the VM “kitchen section” reminded me of ormolu (from French or moulu), a gilding process and design style common to France from about the Renaissance to the 19th century, and I wondered whether these were early examples leading up to the ornate ormolu that we know today.

Ormolu actually refers to the gilding process, but in the antique industry it has also become a broader term for vessels with ornate metal details added to ceramic, glass, and other materials, especially those in the French style. The Ormolu mercury-based gilding process was discontinued in the 19th century due to its toxic nature.

The VM vessels look very much like salt sellers, spice shakers, candlesticks, urns, wine jugs, lamp stands (oil lamps) and other metal or mixed-material accessories that might be seen at a nobleman’s feast. Some have open ends, others look like they may have lids. The one top-left on Folio 88r could be a candle-holder (among other things). The vessels are a bit narrow to be conventional ink stands (although a minority were, in fact, narrow) but ink stands of the time had similar tops/lids. You can see an example of a 19th century ink stand from southern France on Christie’s auction site. An Etsy seller has an example of a Parisian ormolu ink stand that mixes ceramics and ormolu metal details. The VM vessels are colored, perhaps to suit the tastes of the illustrator or perhaps because they are created of mixed materials.

The tall, slender VM vessels might be narrow for ink pots, but could function quite well as shakers or oil jars. In fact, today’s pepper mills are usually tall and narrow. I see very little resemblance to telescopes. Telescopes don’t typically have tripod-style feet or onion-dome lids, nor do they have as many thick-thin variations or embellishments along their length.

Ormolou was fabricated in many places in Europe, but is particularly associated with France, so I looked up the Book of Hours by Duc du Berry, because it was created at approximately the same time period as VM 408. I was curious to see if I could find examples of ormolu or early Renaissance forerunners similar to the Voynich vessels.

The Book of Hours

The Très Riches Heures, Book of Hours, was intended to record historical events and keep track of feast days and times for prayer (like an elaborate journal and religious daybook rolled into one). It is a magnificent set of illuminated miniatures commissioned in the early 1400s by prince Duke du Berry, son to John the Good. It took many decades and a long list of hands to complete the du Berry Book of Hours, but the original artists were from the Netherlands.

The Book of Hours Vessels

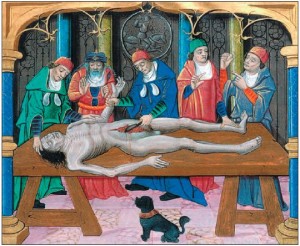

Folio 2r in the Book of Hours illustrates a New Year celebration with jousting in the background and feasting in the foreground. On the left side of the illustration is a collection of apparently gilded vessels associated with the feast. Note how similar in design they are to the VM vessels, especially the base of the wine decanter in the bottom left and the overall shape of the vessel surrounded by others in the top left. There is also a chalice on the table to the far right, partly obscured by a large boat-shaped serving vessel.

I’ve been of the opinion for quite some time, based on studying the Voynich Manuscript, that the VM author is a physician or midwife to a royal court. The author, whether man or woman, obviously was well positioned. He or she had an education, time, and access to writing materials, and a particular interest in the cycles of women’s lives (more about this obstetrical/gynecological evidence in other blogs). It’s intriguing to explore whether the VM author was present at this feast. If the VM author were a physician to the royal court, he might be prominently included among the guests.

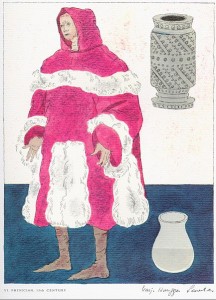

Each region had its own customs and costumes in the 15th century. Some costumes were so specific, you could identify a person’s town of origin, but the picture above left shows one example of a physician’s outfit in the 15th century. Note the colors and style, almost like a contemporary Santa (saint) suit. Now look at the balding man in the red and white suit addressing Duke du Berry (who is seated in blue to the right). Is the man in red a cleric? Or perhaps a physician? Might it be the prince’s physician?

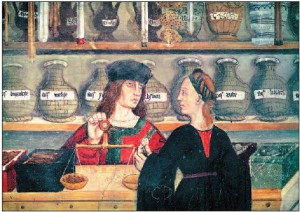

Left, a 15th century Italian pharmacist dressed in red and green. Right, Physicians in wide-sleeved, hooded capes, late 15th century (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris).

Note also that the designs on the jar above the urine specimen container in the picture with the physician’s costume has patterns in it similar to the patterns in the “standing baskets” in the VM. This may be a coincidence, or a sign of cultural familiarity or similarity.

What a revelation it would be if it turned out that du Berry Folio 2r gave us an actual look at the Voynich author—a physician getting on in years desirous of recording his longtime knowledge of science and events of his time. Perhaps the women in the picture, standing behind the man in red, served as models (in the general sense) and were the subjects of scientific study for the women in the VM.

Posted by J. Petersen

Credits: 15th century physician’s costume by Warja Honegger-Lavater, 1962, Wikimedia Commons.