I posted a blog on long-necked Taurus in April 2016, but was reluctant to add a specific picture of a red bull with a strikingly long neck. My focus was zodiac symbols and I didn’t want to include dozens of bulls that were not in zodiacs. I’ve decided to post this one, because the manuscript does have a zodiac series and the bull (which is in a different section) is so strikingly similar to the VMS.

There are two drawings of bulls in the VMS, one painted a little darker than the other. The placement of eyes and style of the nose differ, but their bodies are essentially the same shape:

In another manuscript that predates the VMS by about half a century, we find this drawing of a bull. It’s not a zodiac symbol, it’s in the bestiary section, but it is labeled “Taurus”:

I lightened the background (right) to make it easier to see the shape and pose. Note the long neck, long white curved horns, raised front leg, reddish coloration, very long tail, narrow pointed penis, and landscape background. Even though the background is rectangular and more ornate, the bull is very similar to the lighter VMS Taurus, including the angle of the head.

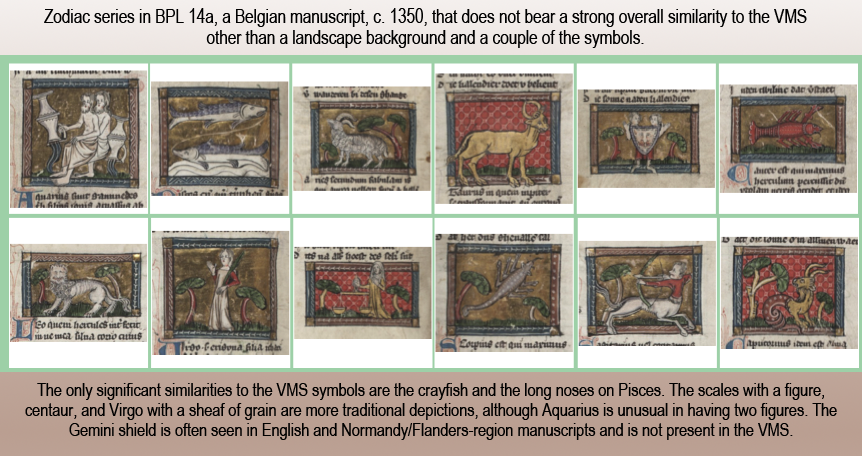

This drawing is more similar to the VMS bull than the one in the zodiac section. The zodiac Taurus is amber and faces the other way (and doesn’t have the front leg raised). The rest of the zodiac is based on traditional symbols and differs from the VMS in a number of ways—Sagittarius is a centaur, Leo has a man-face, the scorpion is more-or-less naturalistic, and the Libra scales are held by a female figure. It fits in with the H 437 tradition in the previous blog. The only significant commonalities with the VMS are the crayfish and the long noses on Pisces.

Are the similarities between the VMS zodiac bull and the bestiary bull coincidental? Why would these two long-necked bulls look so much alike when the zodiac drawings have little in common?

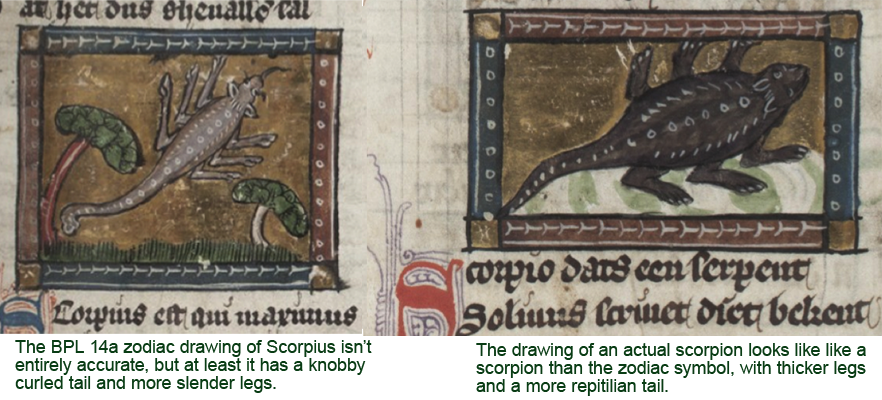

Maybe it’s not entirely a coincidence. If we look at Scorpius in BPL 14a, it is roughly like a scorpion, and yet the scorpion in the bestiary section (right), with fatter legs and body and snake-like tail, leans more toward medieval drawings of lizards and tarasques than a scorpion. Even though it’s drawn at a different angle, in some ways the bestiary critter is more similar to lizard-style Scorpiuses than the slightly more realistic one in the zodiac:

It seems possible that the illustrators of BPL 14a were consulting different sources when drawing the zodiac versus the bestiary. What’s even more puzzling is that the description next to the lizardly scorpion in the bestiary describes the stinger and knobby tail of a real scorpion, and yet these features are not in the drawing.

Crayfish, Centaur, and Libra-with-Figure

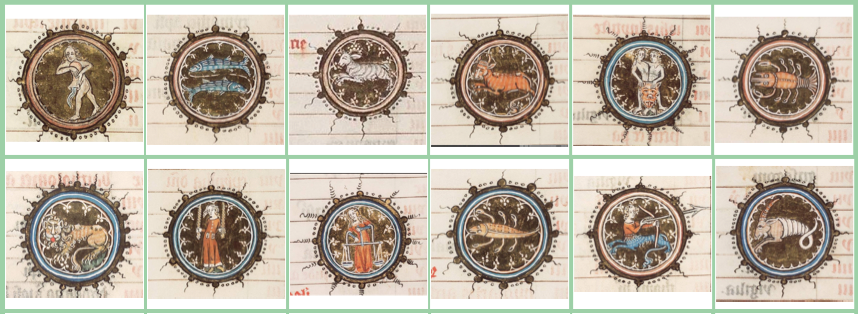

BPL 14a expresses themes that were common to the region, and which continued well into the 15th century, as illustrated by these two examples, one from the southern Netherlands (c. 1360) and a later, similar one in a 1455 Book of Hours (both now in The Hague).

Note how these differ from BPL 14a in colors and the shape that encloses the symbols, but they are the same basic themes: Virgo with grain, Libra with figure, somewhat naturalistic scorpion, shield Gemini, centaur-Sagittarius, and crayfish:

Like BPL 14a, the KB zodiac has Gemini shield, crayfish, Virgo with grain, Libra with a figure, a real scorpion, and centaur Sagittarius. Except for Aquarius and Leo, it’s clearly the same basic template.

Some of the Parisian and Castilian zodiacs follow this template, as well, except that Gemini does not have a shield, as in Egerton 1070, and BL Add 18851 and Add 38126.

Is there a match for Pisces in the bestiary?

Is there a pattern? Can we find evidence that VMS zodiac animals were taken from bestiaries?

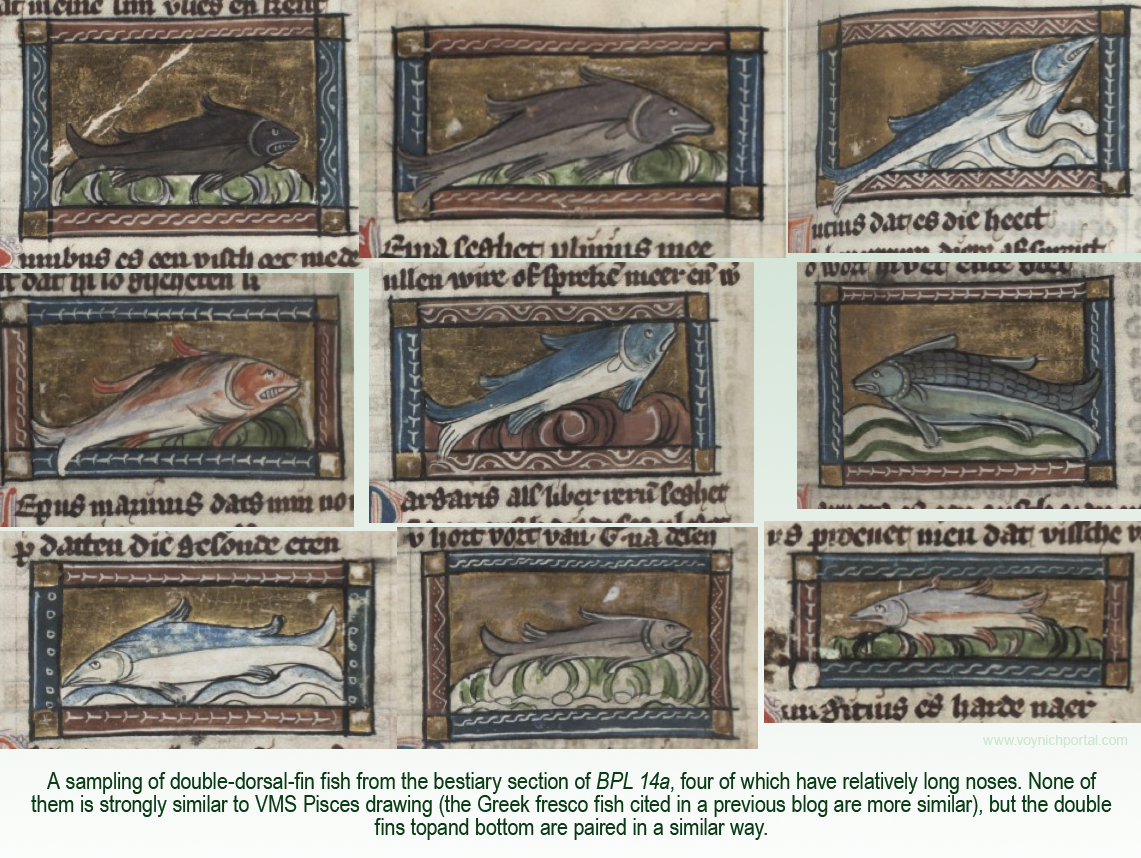

It turns out that the fish section in BPL 14a is fairly extensive, and several drawings have long noses and double dorsal fins. Here are some examples, four of which have notably long snouts:

But… I don’t think they match the VMS as well as the Greek fresco fish mentioned in a previous blog.

What about Leo?

VMS Leo is distinctive for having a long neck (as do several of the other critters), only a hint of a mane, and possibly a furry coat. It has been suggested this might be a panther/leopard rather than a lion, but young lions are shaggy, with spots, and do not yet have manes, so even a cat with skimpy mane could represent a young or female lion.

This drawing in the feline section of the BPL 14a bestiary caught my eye, with the tilted head and its tail through its leg, but it is explicitly labeled “pardus” (abbreviated p[er]dus), so it is intended to be in the leopard rather than the lion family. It’s not posed quite like the VMS, either, but I thought I would include it for reference:

Note the faint suggestion of blue on the VMS lion.

Note the faint suggestion of blue on the VMS lion.

There are a few zodiac and bestiary lions that are blue. Most of them originate in England or northern France/Normandy. The one in Walters W.37 has its tail through its leg, but has a distinctive mane. Trinity B-10-9 has a man-face and Morgan M.729 is posed quite differently (although it should be noted that Scorpius is rather tarasque-like and Gemini is an affectionate couple). Add MS 21926 (below) has a blue lion with one leg raised and only the hint of a mane:

The blue lion in Cotton MS Galba A XVIII (below) might be one of the earliest zodiacs with a blue lion (c. 9th century). It is facing the other way, but interestingly, several of the animals are standing on bumpy terrains, as are some of the VMS critters, and Sagittarius is a human.

The blue lion in Cotton MS Galba A XVIII (below) might be one of the earliest zodiacs with a blue lion (c. 9th century). It is facing the other way, but interestingly, several of the animals are standing on bumpy terrains, as are some of the VMS critters, and Sagittarius is a human.

It has been noticed by several researchers that the crayfish in this zodiac appears to have two heads. However, the zodiac also differs from the VMS in that the twins are male warriors, and Libra is held by a figure. Scorpius appears to be a two-headed serpent, a fairly unique depiction:

But getting back to the blue lion, what does it have to do with bestiaries?

But getting back to the blue lion, what does it have to do with bestiaries?

I think it was Ellie Velinska who first brought this to my attention, but there’s a bluish-gray bestiary feline with a suggestion of fur or spots, a sparse mane, a raised paw, and its tail through its leg that is more similar to the VMS Leo than anything I’ve seen in a zodiac. Note also the very rounded shoulder joint on both the VMS and the bestiary lion:

Glancing through the bestiary, I noticed one other thing related to VMS critters in general…

Glancing through the bestiary, I noticed one other thing related to VMS critters in general…

In the serpent/dragon section of BPL 14a are a number of dragon-like critters that reminded me of the critter nosing a big plant in the VMS, in the sense of being vague and hard to figure out. These all are named, some of them with the names of real snakes (like “boa”), but they do not resemble snakes in any way. Sometimes it’s impossible to identify medieval creatures without the captions:

So what does all this mean?

I’m not sure yet, there’s still much work to be done… the VMS is consistent with a certain branch of zodiac illustrative traditions, as I hope I’ve demonstrated in previous blogs, and yet it’s possible the details, the animals and figures, were drawn from other sources. The VMS illustrator may have studied the zodiac motifs and then plugged in content from somewhere else.

I know that’s easy to say, but not so easy to prove, even if the resemblance of VMS Taurus to the bestiary bull is quite striking. It’s probably a good idea to keep in mind that VMS exemplars might be less obvious than assumed.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2018 All Rights Reserved

This is worth following up.

BPL 14a, as far as I have been able to see in the short time available, contains two parts. The shorter first part includes (among others) a calendar. The longer second part is in a different hand and includes Van Maerlant’s “Der Naturen Bloeme”, a Dutch copy or derivative of Thomas de Cantimpre, which was also the example used for Megenberg’s “Buch der Natur”.

This part starts at fol. 26. It would be of interest to know on which folios your examples can be found.

Both parts are in different hands and may have been conceived as independent books.

There are numerous parallel copies of this work, and most if not all can be related to the city of Utrecht.

It seems of interest to find out the identity and location of the other copies and check their illustrations.

I won’t be able to find the time to do that.

As you know I’m all convinced that the VM Zodiac was loaned from non-Zodiac sources, so I’m not surprised to see a similar picture emerge here between bestiaries-> Megenberg as between 14th century Paris -> Lauber (as we’ve seen for Gemini). That is, relatively well-informed earlier works are used in mid-15th century Germany. The German style is closer to that of the VM, but apart from stylistics, the VM image remains closer to the earlier examples.

So we are likely looking for one or more works from around the turn of the century that had already departed from the formalized style of 14th century French works, yet were still more under their direct influence than later Alsatian MSS.

JKP – this is a question, not a challenge, but I wonder if those pictures you’ve seen of lion cubs with spotted hides weren’t actually images of the American ‘mountain lion’ – the cougar. Sources such as wiki images often caption the latter as (e.g) ‘lion cubs’ but as far as I know African lion cubs only have a bit of striping to the legs and a few markings on the forehead – even then not always and only while the cubs are still quite young. After the Roman era, there were no lions in Europe – at least not according to the wiki summary –

https://www.wikiwand.com/en/History_of_lions_in_Europe

I might also mention that to draw beasts with tails wound around like this was quite common in some of the stonework, and a fairly general convention in art of the Islamic world, as well as in western Jewish manuscripts. It is actually less common in Latin works, though you certainly found some very nice examples.

D.N. O’Donovan wrote: “I wonder if those pictures you’ve seen of lion cubs with spotted hides weren’t actually images of the American ‘mountain lion’ – the cougar.”

No, I’m not talking about American lions. I know the difference. Some Old World lion cubs are spotted. These cubs were born to a pair of African lions and they are distinctly spotted:

https://02varvara.wordpress.com/tag/lion-cub/

Some Asian lion cubs are also spotted. Here are additional examples of spotted cubs from various regions:

http://home.bt.com/news/animals/14-photos-of-lions-and-lion-cubs-to-celebrate-one-of-our-favourite-animals-11363997192561

I’ve never insisted that the VMS cat is a lion, but it has to be acknowledged that young lions have no manes and sometimes spots.

D.N. O’Donovan wrote: “I might also mention that to draw beasts with tails wound around like this was quite common in some of the stonework, and a fairly general convention in art of the Islamic world, as well as in western Jewish manuscripts. It is actually less common in Latin works, though you certainly found some very nice examples.”

The tail wound through the legs is common in many cultures. I’m quite aware that it is found in Jewish and Islamic manuscripts.

But you are wrong about it being less common in Latin works. Lions with tails wound through their legs are extremely common in Latin works, so common, I gave up collecting examples after I found several thousand. They are particularly common in France.

…

In fact, I have almost 70 zodiacs in my collection that specifically depict a lion with its tail between its legs. Only a few are eastern, the rest are western. The eastern Leo is usually paired with Cancer as a crab. The western Leo with tail through its leg is usually paired with a crayfish (80%) and thus more closely parallels the VMS.

JKP – I’m impressed by the ‘long-necked Taurus’ comparison, and would like to quote your finding it. I wonder if you recall which manuscript it came from?

Thank you. I did actually cite the long-necked Taurus at the top, but maybe I didn’t make the relationship clear enough. It is from the same manuscript as the animal pictures just below it (BPL 14a Belgian bestiary, c. 1350).