Introduction

In a previous blog, I noted the similarity in writing styles between the handwriting on the last page of the Voynich Manuscript and the script from a mid-15th century German compendium of literature. While there are many commonalities, probably too many to be a coincidence, there are also a few differences.

Nevertheless, the similarities are significant and the origin of many old manuscripts can be traced by the writing styles. Students of writing are often taught to render the alphabet in a specific way, sometimes even down to the specific stroke order and direction (as in Asian scripts) and, while most will individualize their writing over time, many retain the basic shapes and way of connecting them into adulthood. Thus, one can sometimes see familial relationships in handwriting, especially in the days when parents taught their children to write or hired tutors to come to their home.

Each time I look at the Voynich Manuscript, the style of writing, the way the pages are arranged, the details in the drawings, particularly in the “Map” section and the topography and way in which the map was drawn (including the swallowtail merlins, the “pipes”, the bridges, and the escarpments), I think of four regions: Northern Italy/Southern Switzerland where the borders were fluid at the time, France, Bohemia, and, at times, Naples.

Then I put those thoughts aside and try to understand the information in the VM with no preconceptions about where it may have been written or by whom.

When I started charting the handwriting style on the last page, to try to glean some information about the writer and possibly, with luck, the writer’s identity, I came across something that brought me back to thoughts of the VM’s travels before it came into Rudolf II’s court, and discovered an intriguing piece of information that links 15th century France with Bohemia.

The Second Script Style

As mentioned in previous blogs, “Second Script” is my terminology for the handwriting that may be a different writer from the main VM text. It includes most of the writing on the last page (after some analysis, I decided to call the labels on the zodiacs “Third Script”), and possibly the column of substitution-code letters on the right side of the first page.

As previously discussed and illustrated, VM Second Script closely resembles the script in Der Neusohler Cato. So I asked myself, could I find other examples of similar writing and pinpoint the time period and location where this style of script may have been taught?

In searching old manuscripts, I discovered some notes by an academic with an interest in documenting the Glagolitic language. This excited me for two reasons: 1) the scholar uses a similar style of script to Der Neusohler Cato, but at an earlier time period (indicating a different writer) and 2) of all the languages I’ve looked at, the quirky way in which the VM author used looped shapes seems more in the spirit of cursive Glagolitic than most other languages.

Another thing that struck me about the Voynich Manuscript is the double-c shape that crosses over the stems of some of the other shapes, in the manner of ligatures. Glagolitic is known for its large number of ligatures. The VM isn’t necessarily based on Glagolitic (although the possibility is there), but the encipherment might be based, in part, upon a familiarity with Glagolitic and may have influenced the VM author’s choices.

Details of the Writing Style

The writer who documented Glagolitic is said to be a Slav who lived in the second half of the 14th century, who was at the Sorbonne, in Paris, in the late 14th century. Banská Bystrica, where the Cato originated, is currently in the heart of Slovakia.

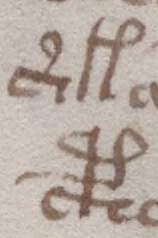

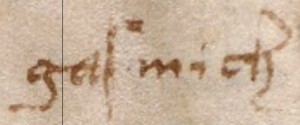

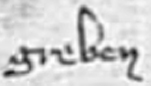

Here is an example of his handwriting (below right) next to the VM Second Script.

Note the “g”, the angular loop, the tail on the last letter and the general spacing and proportions. Also notice the connecting tail on the top of the “g” and the curved right stem on the “g”.

There are some commonalities in general letter shapes with examples of 15th century Bastarda Book Hand from England, but Bastarda is a little more formal and angular and the examples available on the Web don’t match these examples as closely as they match each other.

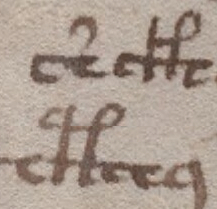

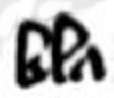

In the following fragments from the Slavic writer and the last page VM, note the angular loops on the “b” and “l”, the tail on the “h”, and the way in which the “a” is somewhat disconnected from its stem.

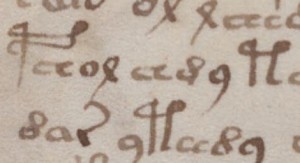

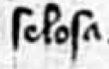

Notice also that the Slavic writer (below left) used the same long flat-looped “d” as the Cato writer used in the earlier parts of the manuscript (below middle) and a “g” and “n” similar to last page VM Second Script (below right).

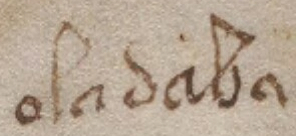

The three hands don’t perfectly match when taking the alphabet as a whole—but there are significant similarities. It’s unfortunate there is no letter “y” on the last page of the VM but it’s possible to compare the Slav’s “y” with the author of the Cato’s “y” (below left) and the Slav’s “looped-x” shape with the VM “looped-x” (below right).

The odds of the Slavic writer being the Second Script author, or even the Cato author, are slim (although it might be wise to keep the idea open in case the carbon dating on the VM is off by five or ten years). He was probably a generation earlier, but could the mystery scribes nevertheless be linked in some way? Could the Slav have given the Second Script writer and the Cato writer handwriting lessons? Might all three of them have studied at the same school or learned from the same tutor? Or could they be related by blood?

Even if there is no familial or household relationship between them, it’s likely they came from the same region, given the similarities in the script, which means it’s possible that the Second Script writer was Croatian or Slovenian, or perhaps a German or English immigrant raised within the Slavic culture.

There’s also a possibility that the VM came into the hands of the Slavic professor very late in his life. Eventually the VM made its way to Rome and the United States, so it’s not impossible that it began somewhere in northern Italy, Croatia, or Slovenia, for example, and made its way to Paris.

J.K. Petersen

Hello from Croatia.

There is a lot element of glagolic ( square and round glagolic ).

Glagolic letters can be used either as simple leters and nombers, letter = number.

It does not mean that is slavic ( croatian, serbs., macedonians…. ) language. It could be possible that some glagolic letters had been used for latin words,names or term, or names or terms on some other language. Also it could be possible that author had been used also pure slavic terms and words.

oliver kosović

I came across this post and I realized the Slavic writer you refer to is the same person I wrote about in my last post. His name is Georgius de Sclavonia. He was a native of Brežice, Slovenia, which at the time was located in the Austrian Duchy of Carniola. The region was under religious authority of the Patriarchate of Aquileia, which allowed Glagolitic and Slavic language in liturgy. Although Glagolitic is usually associated with Croatians, it was also practiced in some parts of Slovenia.

Politically, the Counts of Celje were at around that time Governer of Carniola, and ban of Sclavonia.

The town of Brežice is within a walking distance of the Charterhouses of Pleterje and Jurklošter, where Nicholas Kempf, a native of Strasbourg was a prior. It is likely that he would have heard of Georgius.

Besides, Georgius wrote a book on Glagolitza in 1400, while studying at the Vienna University, where he obtained a doctoral degree.

By the time Kempf came to study at the Vienna University, Georgius was already teaching at Sarbona, but his book on Glagolica most likely remained at the Vienna University and inspired students of Slovenian background to learn from it.

As to the Bohemian connection: During the Hussite war, many Czech monks found refuge in Slovenian monasteries. One of them even authored the Stična Codex, 2-page Slovenian text written with Latin letters.

After the dissolution of the Patriarchate of Aquileia, and the death of the last Count of Celje in 1456, the hope of Slovenian language in liturgy vanished as the Latin was re-introduced. However, the effort to command Slovenian language in written form was still going on and Kemp’s contemporary (but a few decades younger) Thomas of Celje taught Emperor Frideric’s son, Maximillian, to speak Slovenian. https://voynichslovenianmystery.com/

More details on Slovenian 15th century humanist can be found on my web-page