4 July 2019

Medieval manuscripts with herbs are sometimes embellished with images of dogs, snakes, and dragons, often because the plant is used as a remedy for bites, or because it is named after an animal (e.g., dog violet, dragon’s blood). In this blog we’ll look at animal imagery that accompanies a specific plant.

For this example, I selected Aristolochia, a popular medicinal plant native to the Mediterranean.

Aristolochia exemplifies some of the differences in illustrative styles between 1) northern Italian and French manuscripts, 2) branches that include French, Italian, and German manuscripts, and 3) a separate branch comprised mainly of English manuscripts. Plus, it was often drawn with a dragon by the root or, occasionally, a snake, which provides additional information on lineage.

Overview of Herbal Traditions

Most diagrams of herbal illustrative traditions are of this form:

This kind of chart is helpful for an overview of illustrative descent, but it doesn’t help one to see or compare the drawings. So I created a new kind of chart…

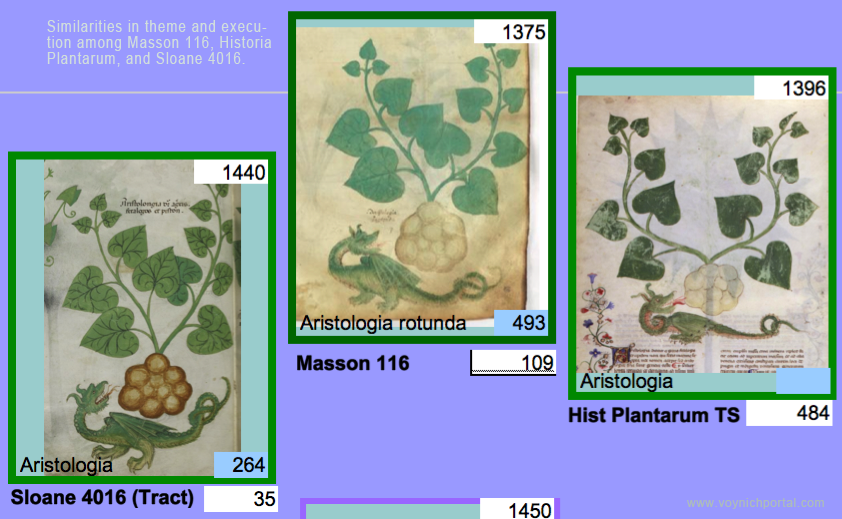

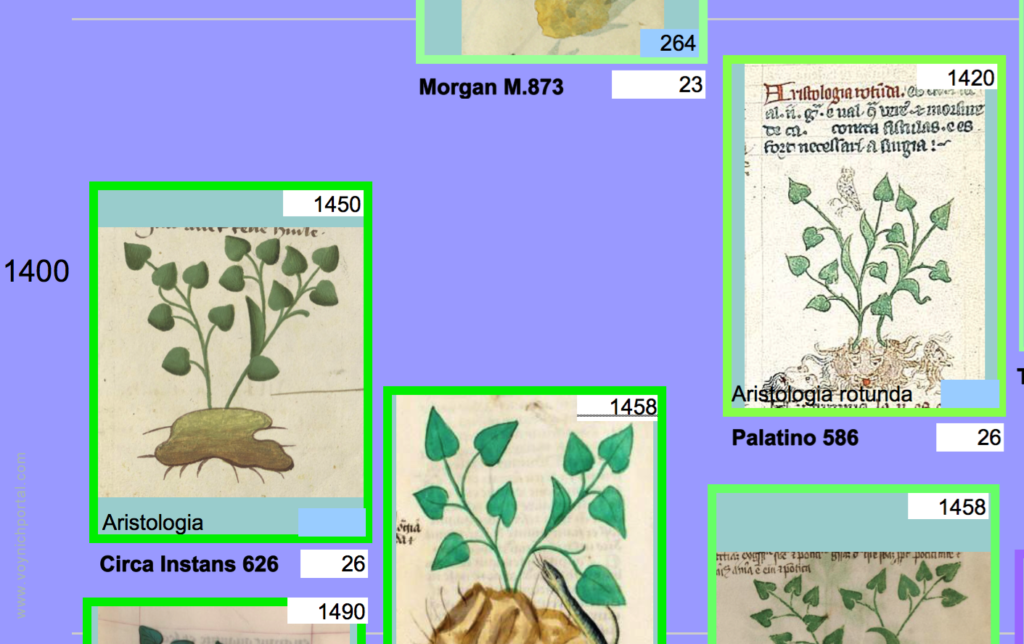

I organized the information so that each dot on the chart is replaced with an image of the plant. I can choose any plant in any manuscript that is included in the files and, in a few seconds, display the relationships among them (this is the result of more than 11 years of comparison, classification, and identification of medieval plant drawings and is still ongoing).

The chart below is a small corner of a very large diagram that compares more than 75 herbal manuscripts from the 6th century to the 16th century (there are also sources from the 17th century, but I have not included them in this VMS-related discussion).

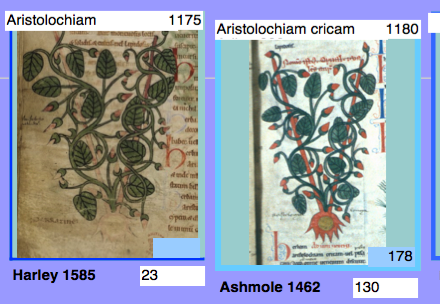

For this example, the English manuscripts are not visible in the first excerpt (they are off to the right), as they form yet another distinctively recognizable group. Aristolochia is not native to the United Kingdom, but it is interesting that it appeared in English manuscripts from about the 11th century onward, usually in a viny style with a round or spindly root.

Harley 4986 stands out from the more typical English manuscripts because Aristolochia longa was drawn with a round root. It may have been mistaken for another plant (it is labeled Aristocia longa but looks like a drawing of Cyclamen).

The Process of Identification

I had some background in plants before I learned about the VMS, and I should point out that visual similarity was not the only criterion for organizing these images. The names of the plants and their spellings often help to confirm the pictorial features, together with the order in which the plants are represented (sometimes even the page numbers match). I consulted textual herbals, as well (those without diagrams). All these flagposts were taken into consideration. There may still be small details to adjust but, for the most part, I believe the IDs to be good.

I’ve simplified the layout for blog display by taking out the relationship arrows. Organizing the chart with thumbnails for each plant makes it easier to compare and contrast the drawings. The dates in this example are approximate (I also have a version that more accurately shows date ranges and their level of confidence, but a ballpark is good enough for a blog post).

Smearwort

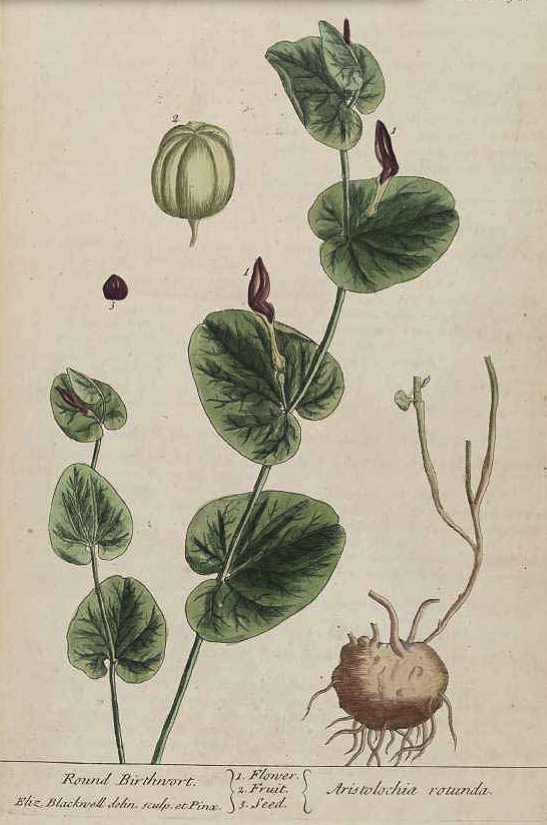

Aristolochia rotunda was known as “smearwort” due to its perceived medicinal value, or “round-rooted birthwort” (Aristolochia longa is a related plant known as birthwort).

In the following illustrations, note the arrangement of the leaves, the distinctively different ways of drawing the root, and the presence or absence of the dragon (in conjunction with the root style):

There are also a few drawings that fall in between the vague root and the round one but, in general, most are obvious copies of their predecessors.

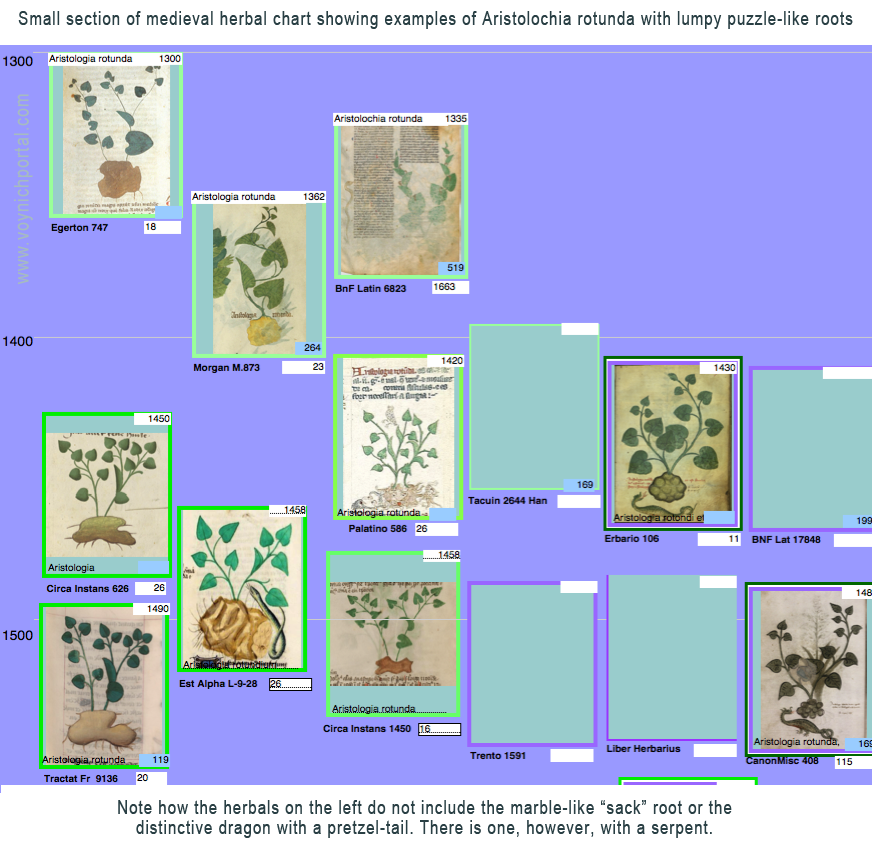

The Lumpy Root

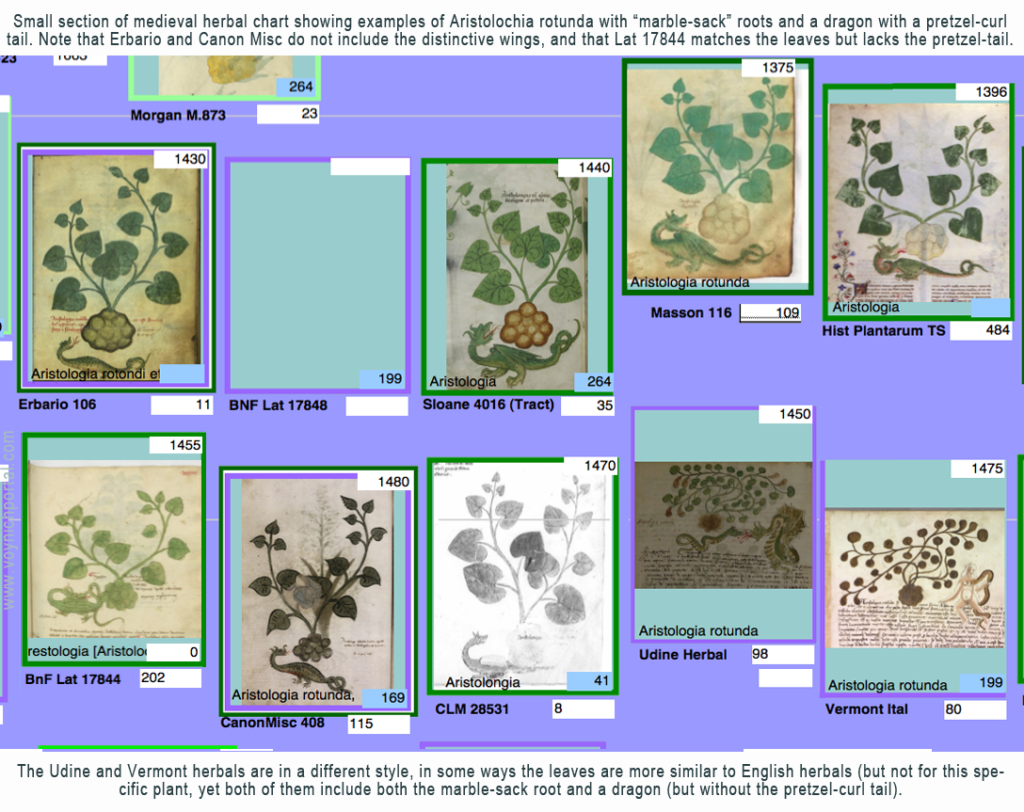

In the following group of manuscripts, the A. rotunda root is drawn like a sack of marbles, with an accompanying dragon, while the roots in the second chart farther below look like vague lumps or puzzle pieces and do not include the dragon (in other words, the dragon only occurs in drawings with a specific and distinctive style of root drawing).

Note also that in the drawings on the bottom-right (Udine and Vermont herbals) the leaves are different (smaller and more viny), and the dragon or serpent is posed differently:

The similarities between Masson 116, Historia Plantarum, Erbario 106, Sloane 4016, CLM 2853, and Canon Misc 408 are very obvious. The arrangement of the leaves and the pose of the dragon are unmistakable. Even the pretzel curl in the dragon’s tail has been copied.

Note however, that the distinctive wings of the dragon are not present in the Erbario and Canon Misc drawings. It’s a small difference but an important one that strengthens the possible connection between Canon Misc 408 and Erbario 106.

The CLM 28531 image is hard to see, but the dragon has wings, so it is more similar to Masson 116 than to Erbario 106 or Canon Misc.

BnF Lat 17844 is of particular interest as it faithfully copies the leaf shapes and arrangement seen in the Masson/Historia Plantarum/Erbario group, and the marble-sack root, but includes small changes to the dragon’s head and tail (it is looped, but not in a pretzel). Thus it is unlikely that BnF Latin 17844 influenced Misc 408 or CLM 28531.

Note that I have color-coded some of the manuscripts, and there are two color-codes around the borders of Erbario 106 and Canon Misc 408. This is because I discovered there were images from more than one tradition in these manuscripts. This demonstrates that not all manuscripts are copied from a single source or, in some cases, that two or more herbals have been bound together.

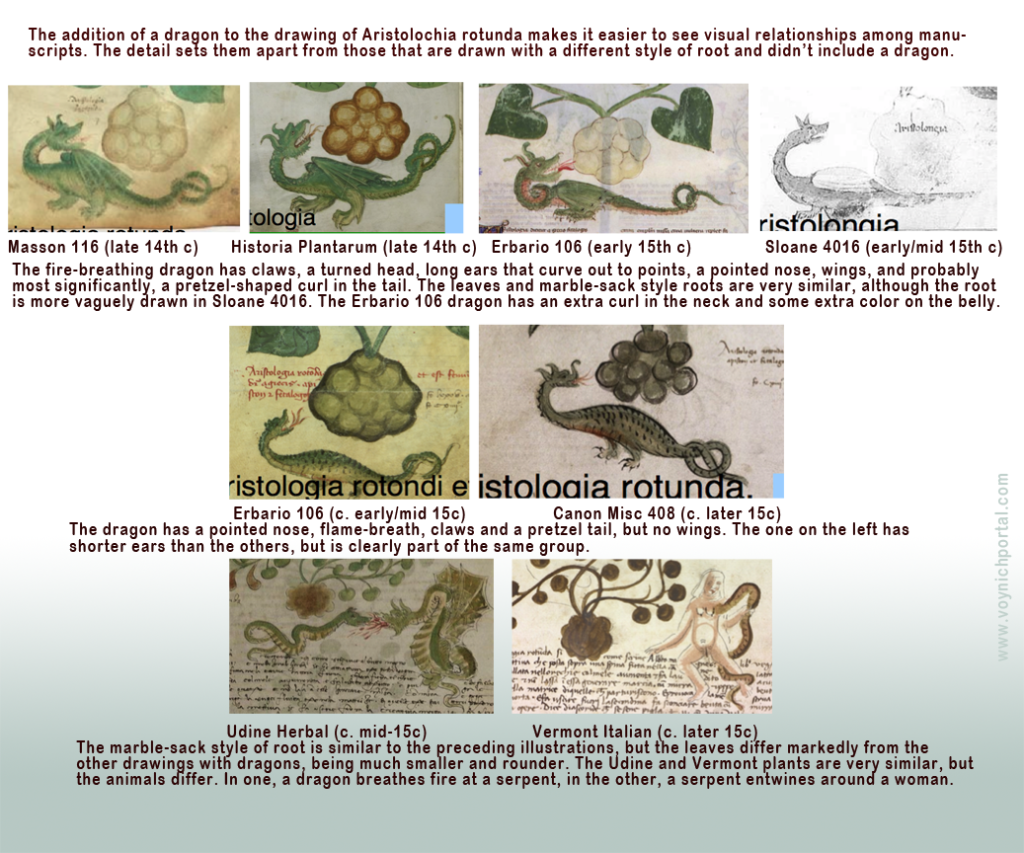

So far, I haven’t found any Aristolochia marble-sack roots with dragons prior to the 14th century. Masson 116 appears to be the earliest (in manuscripts viewable online). Historia Plantarum includes essentially the same drawing and was created close in time to Masson 116. Even the dragon’s wavy out-pointed ears are present:

Scholars are still debating whether the original source for the later manuscripts was Masson 116 or some other exemplar.

Mixed Sources? Or a coincidence?

The relationship between the Masson/Historia Plantarum/Sloane manuscripts and the Udine/Vermont herbals is very intriguing. The leaves in the latter two are smaller and vinier, yet the marble-sack root and dragon are present in the Udine herbal (but without the pretzel-curl tail). The Vermont herbal is exactly like the Udine herbal in some ways, but for this plant, a woman and a serpent replace the dragon.

But the Udine and Vermonth herbals don’t follow the English examples either, which generally feature a round cyclamen-style root and numerous flower buds (in contrast to Aristolochia longa, which were drawn without flower buds):

Note that the textual descriptions in the first group above are quite terse, whereas, they are quite a bit more extensive in the Udine/Vermont herbals and the English herbals. Some of these manuscripts were self-contained (e.g., Historia Plantarum), while others were intended to be used with companion texts that had more information about the plants. Still others were never finished.

The Vaguely Lumpy Roots

Now let’s look at the drawings on the left side of the chart, which are mainly from Italian and French manuscripts. You will see immediately that the roots in the manuscripts on the left are drawn differently from those on the right. They are only vaguely lumpy and don’t look like they’ve been stuffed with marbles.

The leaves also tend to be smaller than the Masson/Historia Plantarum group (except for the Udine and Vermont herbals), and lack the double in-curving vine, and there is no dragon (there is, however, a snake in Estense Alpha which might be mnemonic, as one of the names of the plant is “snake root”).

In the left-hand group, the similarity between Circa Instans 626 and Tractatus 9136 is very clear, and if you pay attention to the larger leaf and the turned leaf, the similarity to Egerton 747 also becomes apparent:

Palatino 586 generally follows the basic plant form of the herbals on the left, but often includes unusual figures. In this case, there is an owl at the top of the plant and three faces in the root. The center one might might be an animal, perhaps a dragon, lion, or a demon. Sometimes I can readily identify the inspiration for the figures in Pal. 586, and other times they appear to be unique inventions. Most of them do, however, relate to the plant in some way:

Dragon Tails

Let’s take a closer look at the dragons, which are drawn in a fairly distinctive style:

There are very obvious similarities between the drawings in rows 1 and 2, even though the row 2 dragons lack wings.

The third group is similar to the first two in significant ways, as in the shape of the root, but there are clear differences in the plant leaves and the way the dragon and serpent are portrayed. Is it a coincidence that the dragon is included with the root? Or did someone see the dragon-style root and then create their own variation?

Here is a closeup of the dragon in BnF Latin 17844, which is essentially the same as the earlier manuscripts but posed a little differently:

The dragon’s neck is curved a little more, and the tail lacks the pretzel, but otherwise it is similar to the Masson/Historia Plantarum and Sloane group.

The Pretzel-Tail Dragon

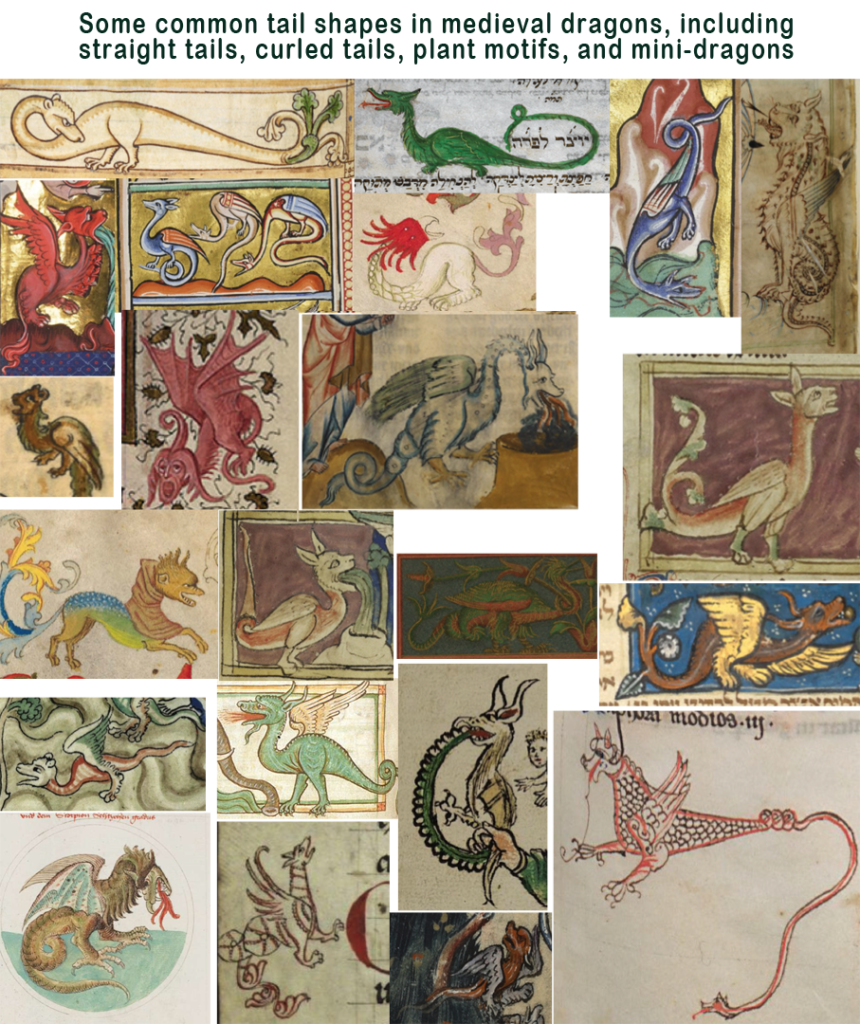

Long ears, flames, and wings are common in medieval dragons. The tail is usually straight or curled, or is embellished like a leaf motif. Sometimes the tail has another, smaller dragon-head. Here are some examples:

Many of these dragons have curled tails, and long wavy ears are easy to find in both Latin and Hebrew manuscripts, but it is difficult to find pretzel tails. Sometimes one can find a clove-hitch tail or a Celtic-knot tail, but they are generally more ornate and decorative than the pretzel-tail:

This Bohemian dragon has a pretzel tail, but it is very tightly knotted, has an unusual right-angle and fleur-de-lis tail, and is drawn in a different style from the ones in the herbal manuscripts, with a scalloped outline:

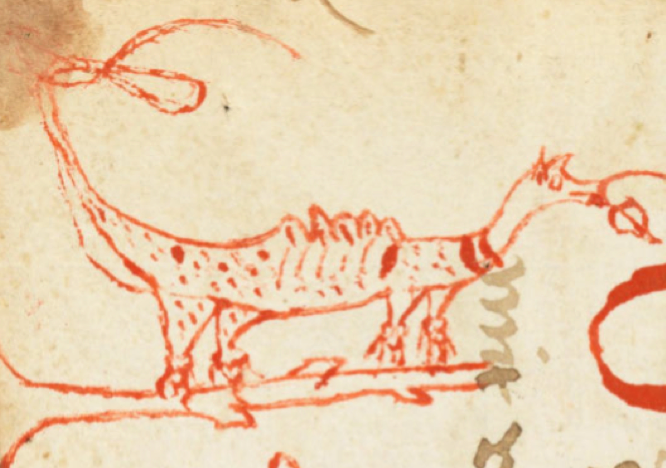

I searched long and hard for examples of pretzel tails and found one that is vaguely like a pretzel in a child’s marginal drawing in a Swiss manuscript:

I’m not sure if this one qualifies. It has a pretzel-tail but also a small dragon-head on the tail. It is early enough to have influenced 14th-century dragons, however, and not all apocalypse dragons have pretzel-tails, so perhaps the twirled tail inspired later artists:

Here is a pretzel-tail without the extra dragon-head, also from an apocalypse manuscript:

I almost didn’t notice these two blue dragons. They are small and tucked away in the corners of very ornate folios. The one on the left isn’t quite a pretzel, it has an extra loop, but the one on the right qualifies:

I was starting to get discouraged. A lot of searching yielded only four manuscripts with pretzel-tail dragons. Then I found this:

This find is significant because these are diagrams in a model book, specifically created for illustrators to copy. There are numerous dragons of different styles, but this one has a pretzel tail, wings, and long curved ears like those of the Masson group of manuscripts. The only problem is it may have been created a few years later and thus could not have influenced the herbal illustrators.

I haven’t located enough pretzel-tails to generalize about their origins, but the above examples are from England, France, and southern Germany (and possibly Bohemia for the one that is tightly knotted). One thing is clear, they are not common, but they are apparently not localized either.

So let’s get back to the plants, and the Voynich Manuscript…

Is Aristolochia in the VMS?

Are there any drawings in the VMS that resemble drawings of Aristolochia rotunda?

In general, medieval drawings of Aristolochia are slightly viny (some of them are distinctly viny), and most of them have heart-shaped leaves. The arrangement of the leaves is not very accurate—sometimes alternate, sometimes opposite (in real life, Aristolochia leaves are alternate, and lightly clasp the stem).

Flowers are usually only shown in English manuscripts, most of the others omit them. The flowers are in between the leaves. No one drew the seedheads, which look like tiny indented green watermelons.

What about the VMS “dragon” and the nearby plant?

There is a small critter that vaguely resembles a dragon on VMS f25v but the plant has elliptical leaves arranged in a rosette and does not look like Aristolochia. Some have suggested this is a dog pulling out a mandrake plant, but the leaf veins are wrong for mandrake and mandrake was almost always drawn with berry-like fruits and a parsnip-like root.

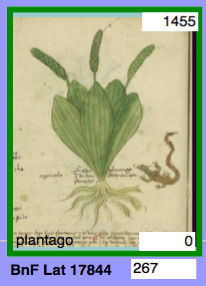

Plant 25v is far more similar to plants like Plantago, False Hellebore (Veratrum album), Lilium, and Dracaena—plants with parallel veins and whorled leaves—than it is to Aristolochia.

Plantago is not usually shown with a dragon, but there are rare exceptions, as in BnF Latin 17844, which has a long-tailed dragon to the right of the plant. I am skeptical of there being a connection based only on this, however, because the 17844 illustrator drew numerous dragons.

Perhaps VMS 27v could be considered for Aristolochia. It’s slightly viny and has a puzzle root, but the flowers are completely wrong, the leaves are not heart-shaped or clasping, and the leaf margins are distinctly toothed, so I think 27v (left) is more likely to be something like Agrimony rather than Aristolochia. Agrimony even has a little star-like frilled calyx when it starts to go to seed—similar to the frill on the VMS flowerhead, and there are other plants with distinct frills.

One VMS plant that might qualify as Aristolochia is Plant 1v, which is somewhat viny, has a big lumpy root, and a rounded seedpod. However, there are other plants, like Hypericon and Nightshade that resemble VMS 1v more, and it’s possible the root is mnemonic rather than literal (it looks like a cross between a bear claw and a lump of fabric), so an ID of Aristolochia is tentative.

Summary

It was fun to look for dragons, but I haven’t seen a match for the Masson- or Udine-style dragon in the Voynich Manuscript. I’m not even certain the little critter on 27v is a dragon. Maybe it’s a giraffe-camel, or a turtle with long ears.

As for Aristolochia, lumpy roots can be drawn in many ways and the VMS small-plants section doesn’t include the whole plant, so it’s difficult to identify them with any certainty, but it’s possible that Aristolochia (rotunda or longa) is in there… somewhere.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved