27 26 July 2019

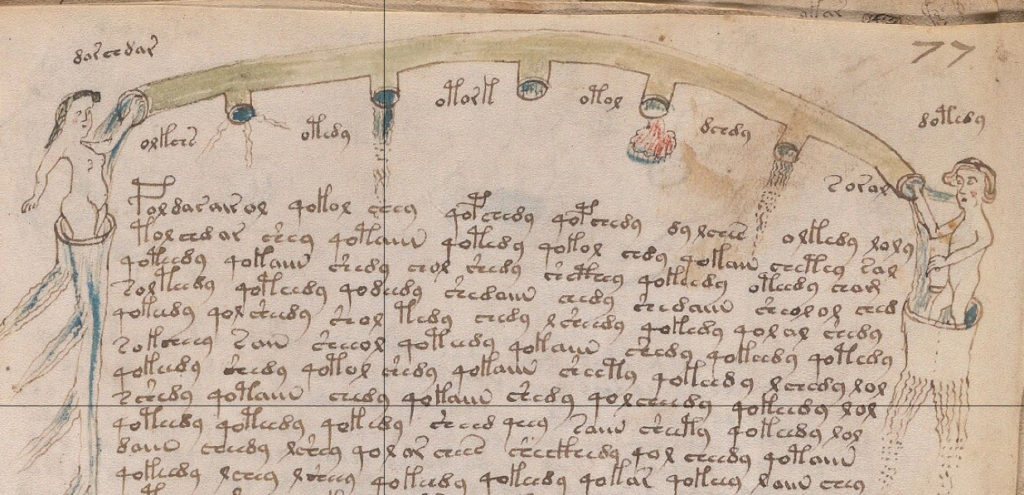

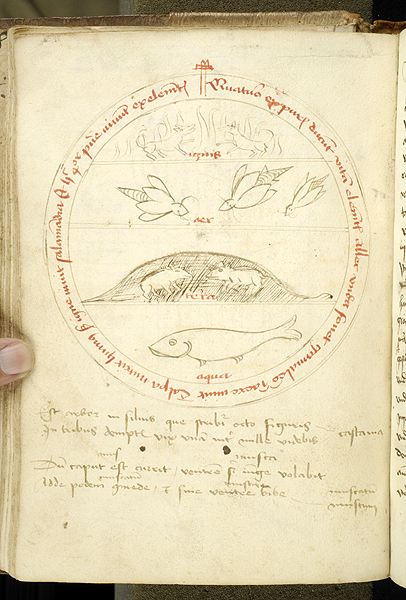

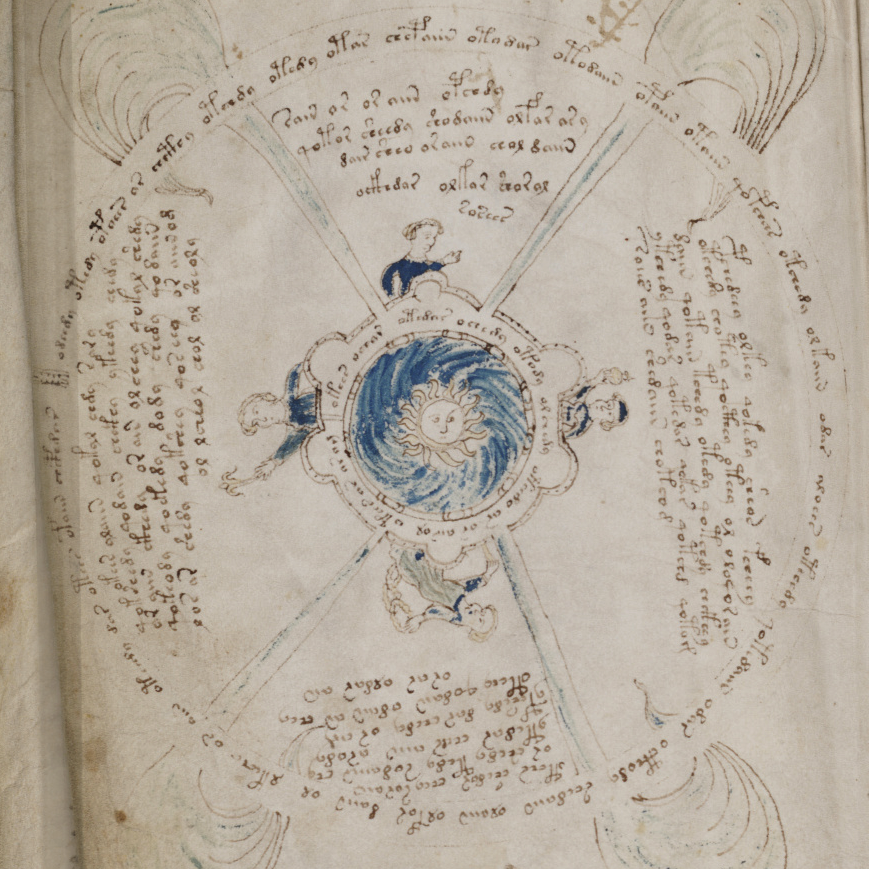

The VMS image at the top of folio 77r is often interpreted as the four elements (air, earth, fire, and water). But there are five pipes, not four. I did find one medieval representation with a fifth component in the center called null, and some conceptions include a fifth “element” as spirit, aether, or void, so it’s not unreasonable to suppose the diagram might represent elements:

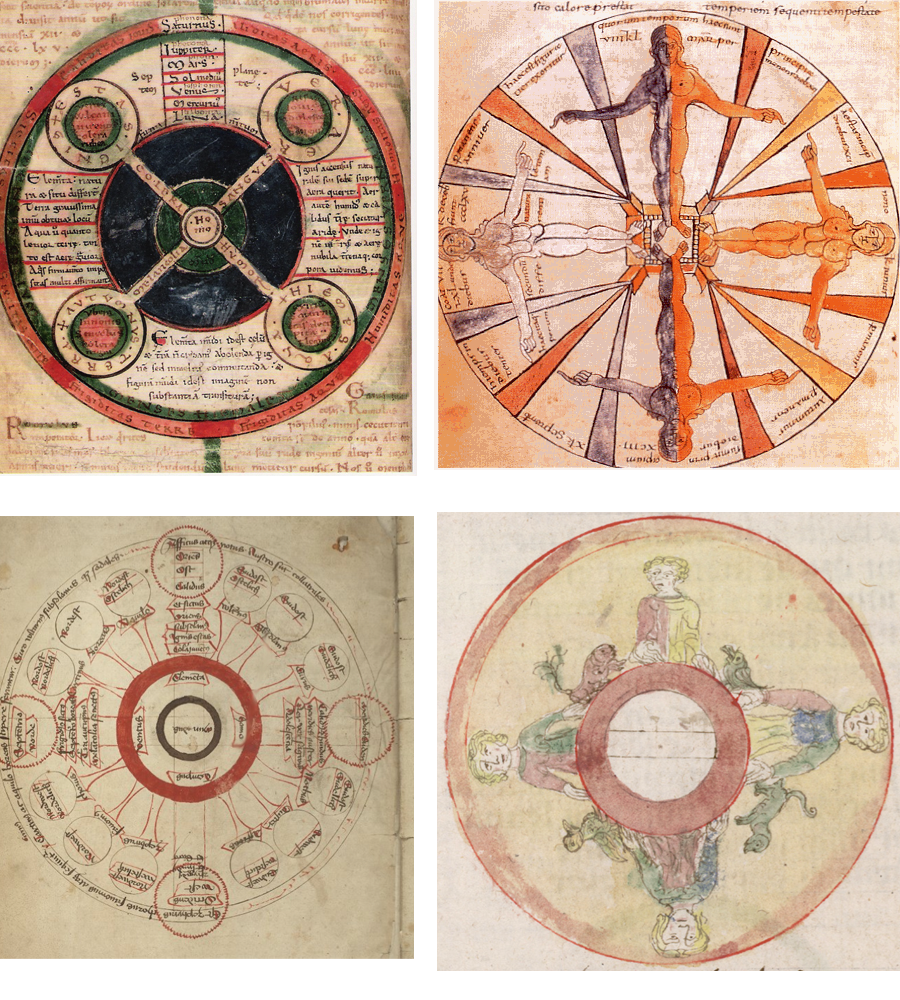

Medieval representations of the elements took many forms, from simple lists and block drawings to elaborate illuminations. Some of them take their cues from ancient writings:

Yes, even things which we call elements, do not endure. Now listen well to me, and I will show the ways in which they change. The everlasting universe contains four elemental parts. And two of these are heavy—earth and water—and are borne downwards by weight. The other two devoid of weight, are air and—even lighter—fire: and, if these two are not constrained, they seek the higher regions. These four elements, though far apart in space, are all derived from one another. Earth dissolves as flowing water! Water, thinned still more, departs as wind and air; and the light air, still losing weight, sparkles on high as fire. But they return, along their former way: the fire, assuming weight, is changed to air; and then, more dense, that air is changed again to water; and that water, still more dense, compacts itself again as primal earth.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Book 15

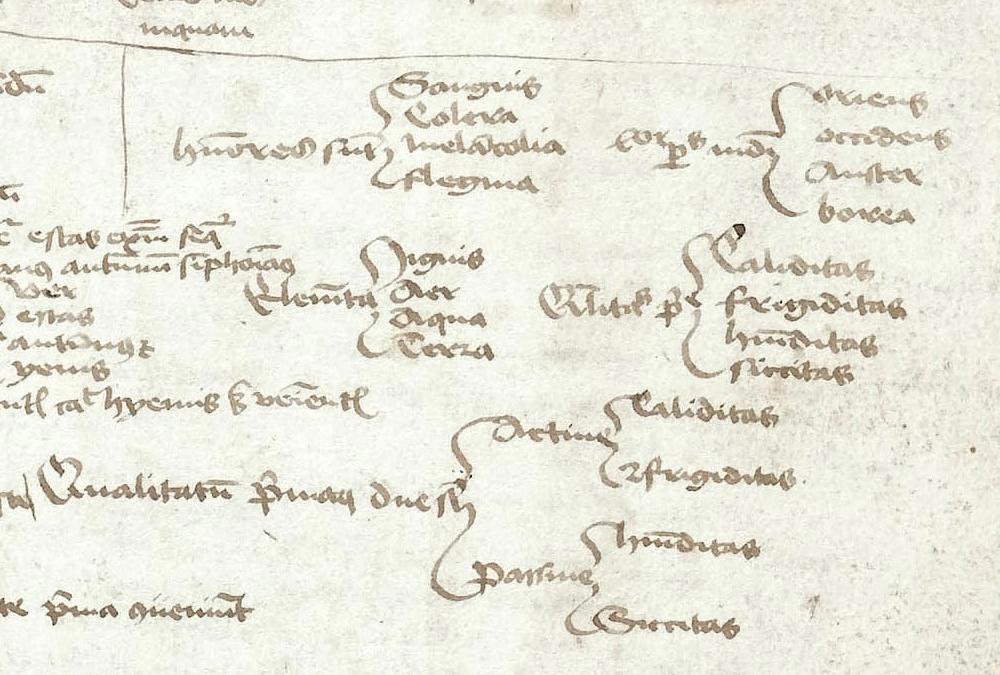

Sometimes an effort was made to relate elements to other concepts that fell into groups of four, eight, or twelve.

I didn’t want to assume the mysterious emanations from the VMS pipes were elements without investigating other possibilities, such as

- traits (hot, cold, wet, and dry),

- humors (black or yellow bile, blood, or phlegm), or possibly

- temperaments (sanguine, choleric, phlegmatic, or melancholic)

- the four Anemoi (Oricus, Occidens, Auster, Borea),

- seasons (spring, summer, fall, winter), or

- stages of life/wheel of fortune.

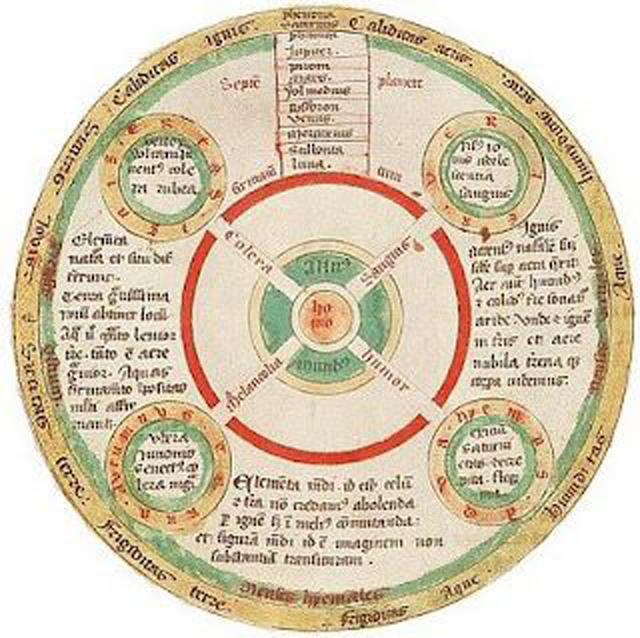

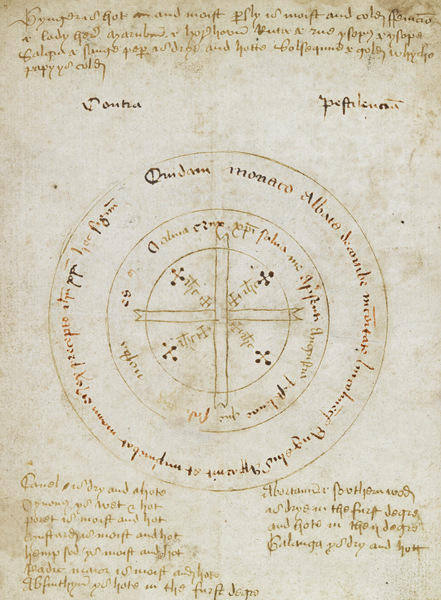

In the following chart, we see Ignis, Aer, Aqua and Terra in the center, above which are the four humors, and to the right a group of hot/cold/wet/dry traits that are frequently associated with medicinal plants:

Levels of Complexity in Medieval Charts

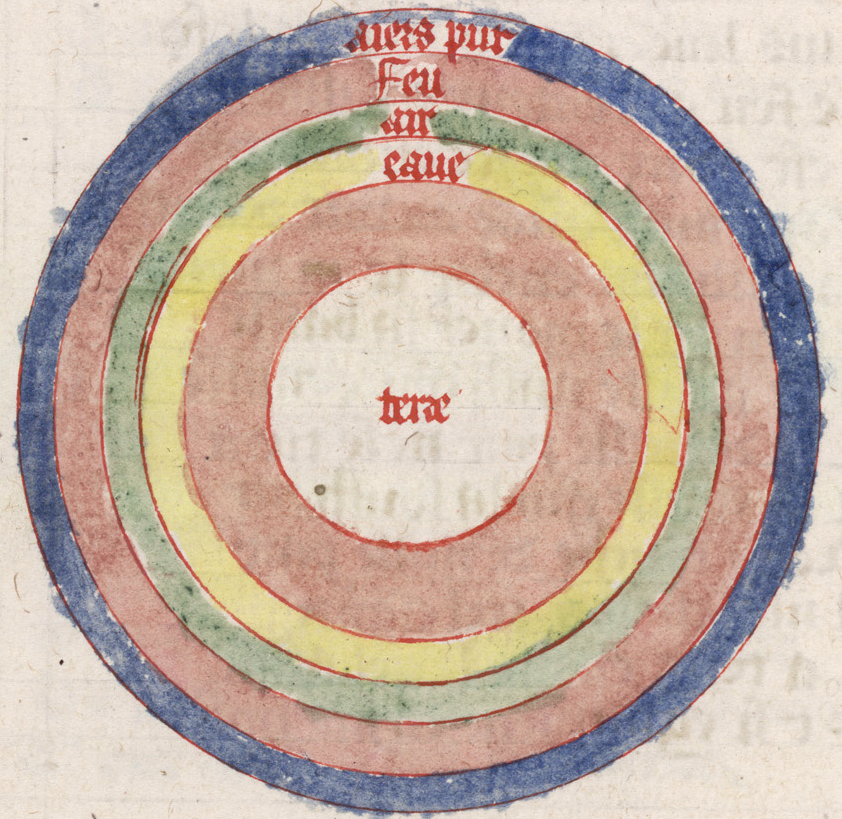

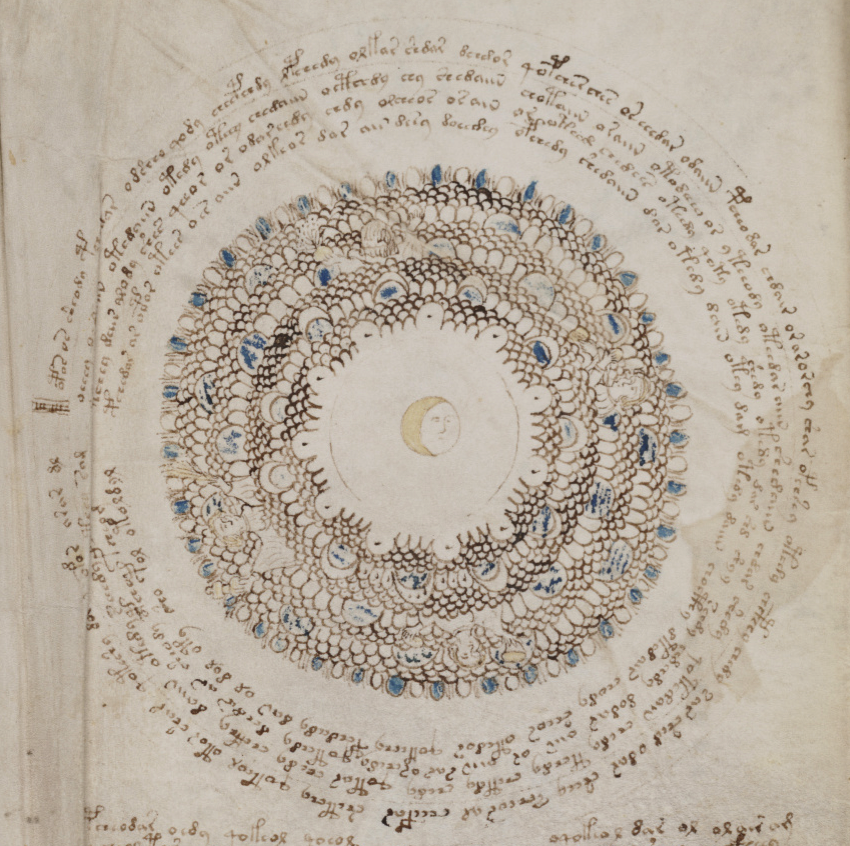

Simple visual charts conveyed many of these basic ideas. This chart displays the elements in rings, beginning with earth in the center:

Noe that there are five labeled rings, with a dark-blue ring on the outer edge called aiers pur

Sometimes there is no text. The colors and shapes tell the story, or the text is separate from the diagrams:

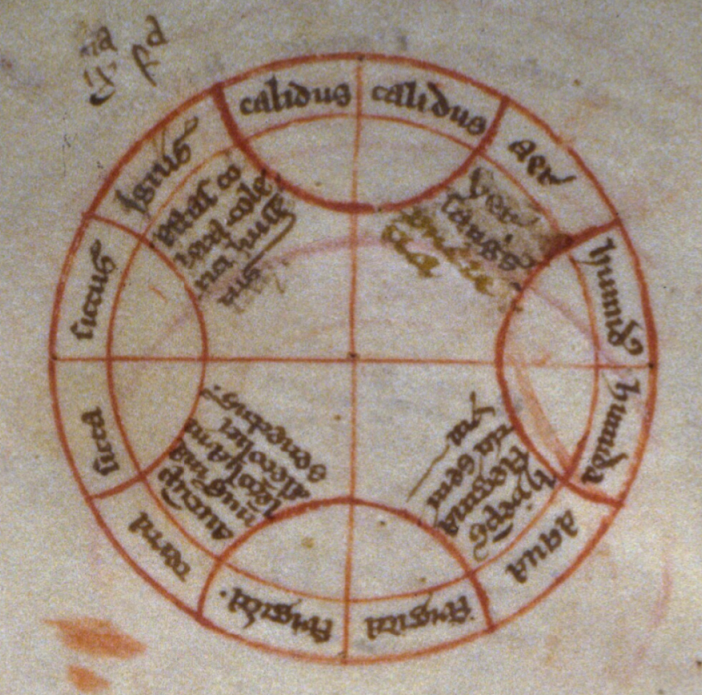

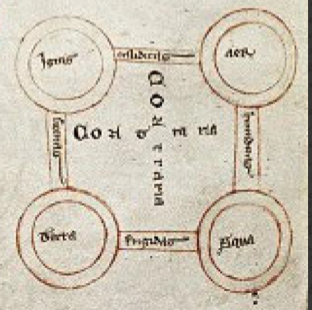

This simple 13th-century chart interposes traits between the four elements. Later in the manuscript the same idea was drawn with slight differences, as though the illustrator were experimenting with ways to present the information:

Arrangements varied considerably. This is one of the less common ones, from a mid-15th century medical/astronomical text. The elements are stacked within an enclosing circle in a different order from the preceding Huntington diagram, (aqua, ter[r]a, aer, ignis).

Note the marker at the top of the chart, and the numerous Latin abbreviation symbols that encircle the diagrams (characteristics similar to the VMS). This is a small-format manuscript (207 x 145mm):

Another diagram in Digby 107 places the elements Ignis, Aer, Aqua, and Terra in the corners, with connections through hot/cold/wet/dry along the sides. Contraria forms a cross in the center:

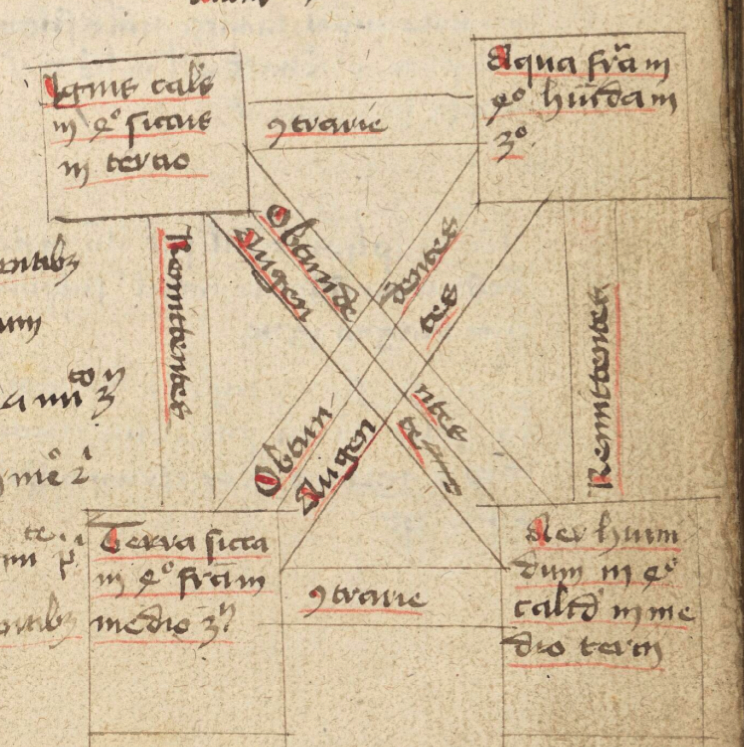

Here Ignis, Aqua, Aer, and Terra are also in the corners, along with their associated traits. There are conceptual connections through the sides like the previous diagram, except that “[con]trarie” is on two of the outer connections instead of in the center, with “Remitentes” on the other two sides. Further connections have been added cross-wise to connect the corners:

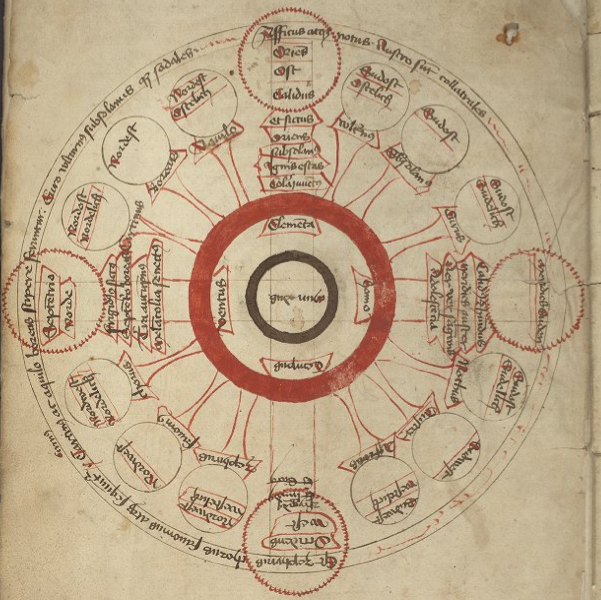

Coming back to Morgan MS B.27, sometimes the elements were related to humans rather than to a schematic of the heavens, a trend that became more prevalent in the century after this was created, with the rise of humanism (which had a greater emphasis on independent, scientific thought and the individual). Note the lines in the background form a shape similar to the divisions used for medieval horoscopes:

In the next example, temperaments, traits, and elements have been further related to the constellations on the ecliptic (the zodiac constellations):

The following diagram lists the elements and traits around the outer edge and the humors in spokes radiating from the center. It includes a schematic illustration of the moon, “planets”, and stars at the top (the Sun was in the middle of the planets because it was wrongfully assumed it orbited the Earth):

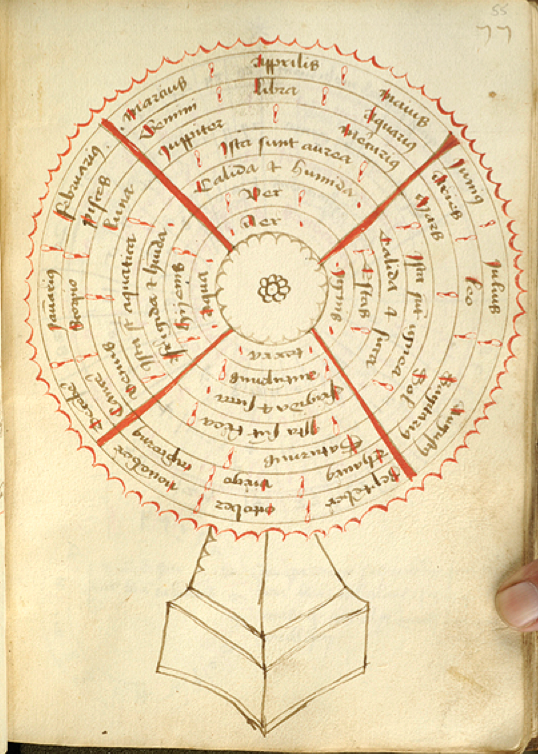

Morgan B27 has attracted the attention of Voynich researchers due to the little flower-shape and text within concentric circles, but I was also intrigued by the content, which includes elements, traits, plants, zodiac constellations, and month names:

Note that the month names are Ianuari[us], Februari[us], Marcius, Apprilis, Maius, Iuni[us], Iulius, August[us], Septe’ber, October, Nove’ber, and Dece’ber. The language/spelling is different, but some of the abbreviation symbols are the same as the month-notes added to the VMS zodiac figures.

Sometimes these various schema (left) were combined with concepts of gravitational forces, as in the two examples on the right. It was common to illustrate gravity as people standing on the earth on four sides with their feet anchored to the ground. The diagram bottom-right is a little different because it includes animals with the people:

Sometimes the gravity diagrams include “tunnels” toward the center of the earth or a rock plummeting into the center. The following diagram is primarily to illustrate gravity (note how the characters are slouched as though they are being pulled toward the globe):

I thought it might be possible to relate the figures on VMS 57v to temperaments or one of the other groups of four, but it’s hard to explain the various parts of the drawing as a cohesive whole and I prefer K. Gheuen’s idea (I wish I had thought of it), described in this blog about the wheel of fortune:

Toward a Concept of a Unified Whole

LJS 449 has one of the more complicated charts, where everything except the kitchen sink has been crammed into one diagram. If you have read my blog about mappae mundi you may notice that this chart is oriented in the common way of the time, with east at the top, the direction of the rising sun.

The traits and temperaments are beneath the four corner circles and between them are the 12 winds. Note the space-filling “justification” squiggles between the text blocks in the outer circle:

So those are a few of the medieval concepts that might be creatively illustrated with something emanating from pipes, or perhaps in a wheel with four people with their feet pointing toward the center, as in VMS 85r2:

Could 84r2 be a diagram of gravitational forces?

Maybe, if it has been combined with other ideas (like the four temperaments), but it would be unusual for a picture of gravity to have the sun in the center unless this illustrator knew something other people at the time did not (that the core of the Earth is intensely hot, or that the Sun was a prime gravitational force in our solar system, a heretical idea).

The diagram on the facing page also has four figures, each one holding a different object (possibly an attribute), with a moon rather than a sun in the center, suggesting a connection between the two folios:

There are two full pages of text between this diagram and the next one, so perhaps this section was important to the designer in some way.

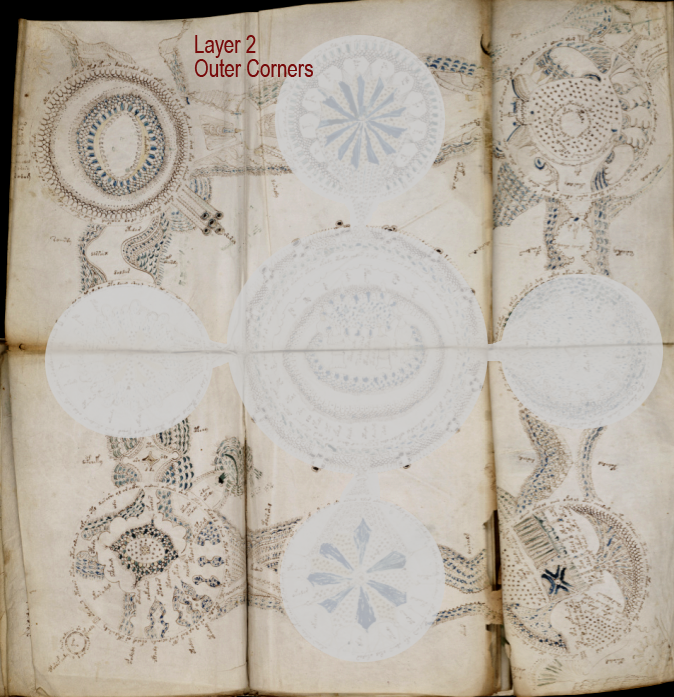

Following these textural/figural rota is the foldout “map” that nay also incorporate fourfold schemata, as discussed in previous blogs. Perhaps the four corners are fire, water, earth, and air:

Other Possibilities

Magical diagrams are sometimes organized in groups of four.

Here is a 15th-century charm against the plague from the Leechbook (Wellcome Library) drawn in a style similar to humors and temperaments:

The text in charms often consists of names of angels, prayers, and “power” words (some of which can be traced back to ancient times, while others are a mystery). Sometimes they are accompanied by medicinal recipes.

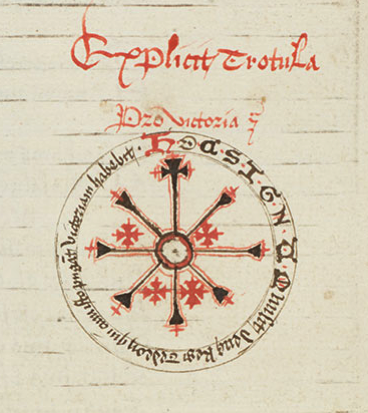

Here is a similarly constructed talisman for protection in battle:

But maybe VMS 77r has nothing to do with elements (in the schematic sense), or humors, traits, temperaments, or charms. Maybe it’s part of a story.

Could the various emanations from the pipes and cloudlike textures represent hail, rain, fire, and blood as described in classical literature and biblical passages?

If so, then perhaps the figures in loges on either sides are celestial beings—God’s emissaries carrying out his wishes (which apply to several religions, not just Christianity), and the ones on the lower left of 77r might be dishing out storms, floods, and other natural disasters.

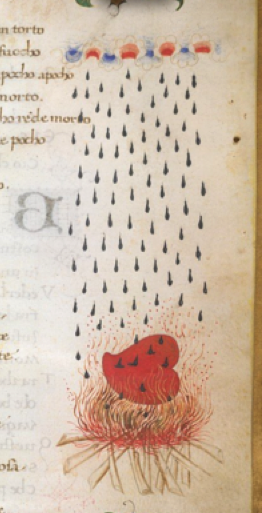

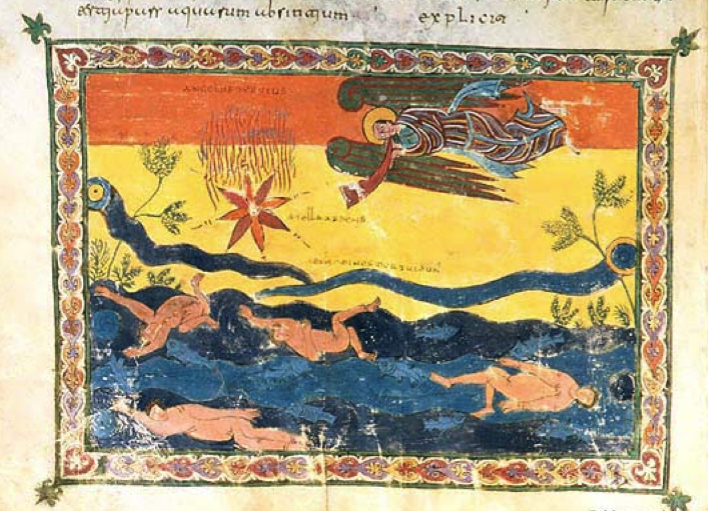

Here is a 12th-century illustration of a tempest of fire, hail, and blood:

Illustrations of plagues and calamitous weather are also found in Hebrew manuscripts, such as “the plague of hail” in the Hispano-Moresque Haggadah, Castile, c.1300.

More of this occurs in Morgan M.644. Here the emanations are accompanied by a plague of scorpions:

As an aside, note how M.644 uses a band of stars, rather than a cloudband, to define the celestial borders (above and right). This is more like old Egyptian borders on friezes and coffins than later medieval cloudbands, but the context is the same.

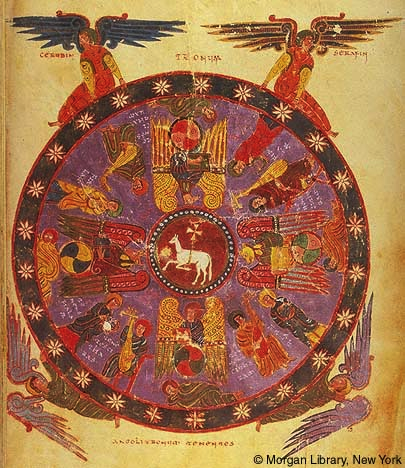

M.644 also incorporates numerous groups of four, including winged beings, four discs with dark-light slightly spiraled patterns, and 24 stars in the perimeter (6 groups of 4) and, in the center, the lamb of God (looking more like a horse than a lamb):

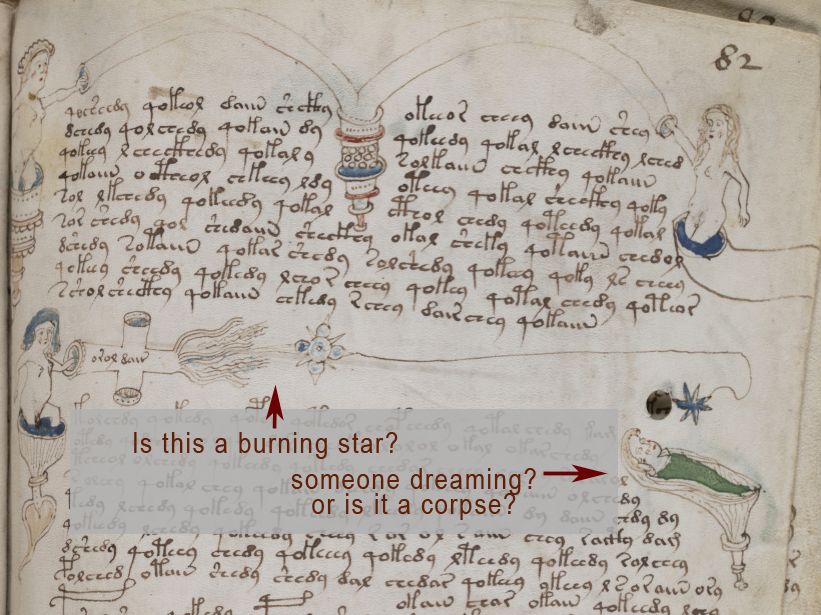

In this early Spanish illustration, there are streams and corpses and a falling, burning star, with an angel (a clothed nymph?) orchestrating events:

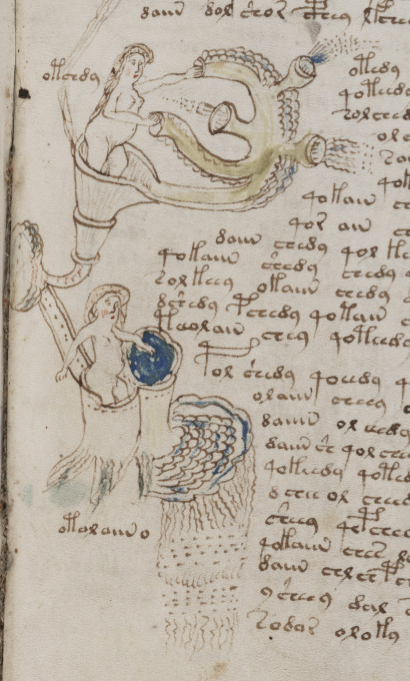

Is the same theme in the VMS? If we pretend nymphs in airborne loges are divine beings, are they working the celestial machinery?

I’m beginning to think that the VMS nymphs aren’t nymphs at all. Maybe we should think of the ones in loges as “celestial engineers” who alternately guide the viewer or orchestrate earthly events. If so, perhaps the pipes at the top of 77r have more to do with natural elements or mythical calamities than the classifications of Aristotle.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2019 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

_______________________________________________________________________

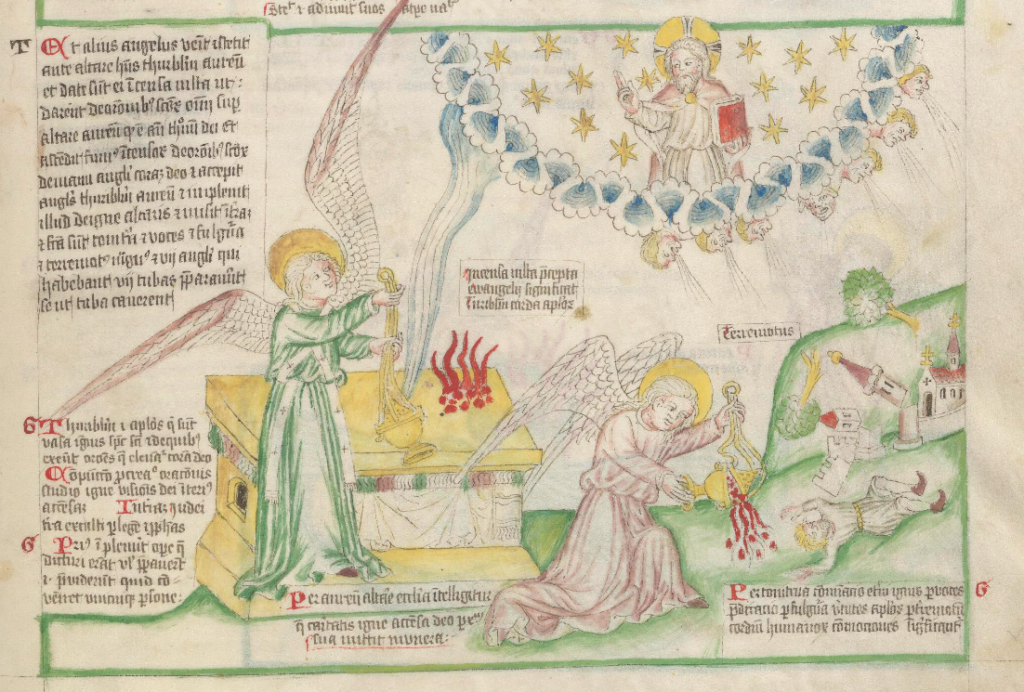

Postscript 21 August 2019: If you scan back through this blog, you will see that I posted an image of “the first trumpet” from a Beatus manuscript, with textures streaming out of the end of the trumpet. This image exemplifies the point of the blog—that streaming textures don’t have to be Aristotelian-style elements, they can be other things, including temperaments, humors, sound, messages, or biblical-style calamities.

The idea that the poofs coming out of the VMS pipes might be something other than earth, air, fire, water, and spirit/aether has haunted me for years, but it wasn’t until I started focusing on Agnus Dei, early this year, that the idea of calamitous weather hit me, as well.

I was reluctant to post this blog because I knew I had another image in my files that included not just one trumpet, but several—but I couldn’t locate it among my terabytes of VMS imagery and my blogs tend to sit for a long time in Draft mode when I can’t find a specific image, so I posted it anyway.

I found the missing image today and have cropped it to emphasize the part with the trumpets. Note how each angel at the level just above the Earth has wings of a different color, just as the emanations from each VMS pipe is a slightly different texture or color. Four of these angels have trumpets, and one is dispensing emanations from a lidded chalice (a chalice often refers to Christ’s blood as a metaphor for spirit or the Godhead), so we have 1 + 4 to possibly match 1 + 4 in the VMS “pipes”:

Imagine that the nymphs on either side of the VMS folio in their respective “zoomers” are angels in charge of dispensing God’s commands. Also imagine that the VMS pipes are metaphorical trumpets, and each poof out of a pipe is some sort of calamity (e.g., rain, wind, fire, hail). Fire and hail (and sometimes frogs) were especially popular in terms of heavenly onslaughts. It’s possible the empty pipe refers to wind or to spirit in much the same way as the lidded chalice of blood sometimes refers to spirit or spiritual redemption (it is sometimes also a flaming chalice).

I don’t know if this is what the pipes represent, I still think temperaments, humors, or traditional elements are possible, but since this images helps clarify one of the possibilities I haven’t seen suggested by other researchers, I wanted to share it with readers.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 27 July 2019 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

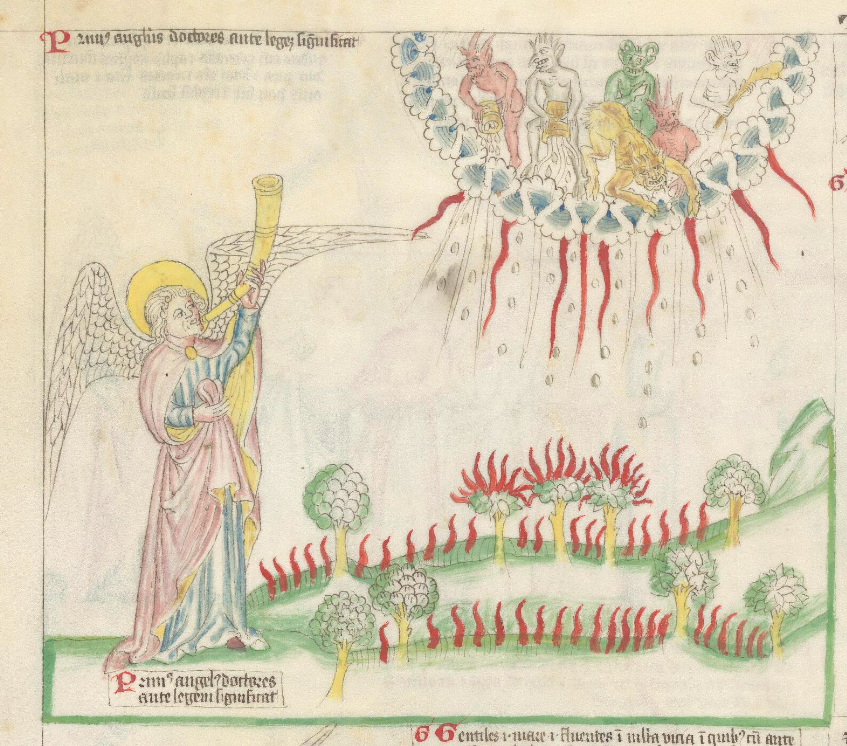

Postscript 13 May 2020: Here are two more drawings that illustrate how the textures coming out of the “pipe” on f77r might not be elements in the medieval scientific sense but, alternately, could be forces of nature like wind, water, fire, and hail, as suggested in this blog.

These are from the Wellcome Apocalypse (MS49) and they show the various calamities that could be “rained down” by God if people didn’t behave themselves (with thanks to Arca Librarian for pointing out that this manuscript is now online).

Note the different textures used for each form of weather:

My view is somewhat connected to the fire earth water air idea, but even more literally connected to the earth itself, along with its many waters and fires.

I see this tube as showing the Danube river. The tube as river icon is not without precedent in historical cartography. Note that the tube starts out with blue water, the tube is green, then becomes more brown at the right side. I think this shows the direction of flow and that sedimentation occurs along the way, muddying the waters. The first emanation from the tube is thermal water, (you can see similar squiggly lines on f84r and f77v which i see as also relating to volcanic subterranean water flow) or water+fire, then water with sedimentation, or water+earth, then water only, then heated water which makes steam, or water+fire=air+water, then sedimented water again, ending with the male nymph and his dual sediment spewing ends of the river delta he stands in. The fact that it is a male nymph is important, i believe this only happens when the place is referred to again on another page, in this case f82v has a female nymph with a spindle that stands in the same spot, but we get to her via a route through the Aegean, Marmara and Black Seas, rather than up the river. This river delta is often drawn on maps with a Y shape.

Coincidentally, cities along the Danube have similar traits. There is Bad Abbach, a spa town near Regensburg, and Munich to the south also has thermal springs, Vienna has sediment issues, Bratislava had just become a new city in the early 1400s, and may be analogous with the water only emanation, Budapest has many hot springs and thermal baths, and Belgrade is in the region that has the most sediment of all, especially in the Iron Gates to the west of it.

The lower left nymphs show sedimentation issues as well, on the western Adriatic and Ionian shores. The upper diagram shows a river complex through a mountainous area that has eroded into a complex bay. The next page takes us to the Aegean Sea.

I don’t see apocalyptic details on this page per se. I recognize many of the images from the Beatus tradition, the seven Trumpets, the Wormwood star, the Cherubim, Adoration of the Lamb, etc. (I think the dark light patterns in the breastplates are fire, brimstone and garnets…ties in with the volcanic activity i jeep seeing all over the quire) and i do believe they are referenced, if not directly, then by some of the mountain and vegetation imagery therein, from the world maps that are generally included in the Beatus Commentaries. Overall i do see the water and fire and earth connections to apocalyptic possibilities, especially insofar as volcanic activity and flooding, burning mountains falling into the sea could happen literally, as well as figuratively, in terms of asteroids.

But, I don’t think it is a burning star in the last image, it is a flow into the sea, and a compass rose to say you’d better know how to sail, since you are now in the open ocean, after leaving the Baltic sea or a river flowing into this sea. The line is the shore of Europe from Denmark down to Portugal, the turn is analogous to the Bay of Biscay, the last bump is to avoid the shore of northern Spain and the part of Portugal along the way. The dreaming nymph is home in her bed shaped like the entrance to the Tagus river on which Lisbon is found, or the shape it was before sediments changed it to what it is today. This concludes the trip around Europe by sea and river and ocean, and corrects the beginning passage by ending at the true most westerly point, Cabo da Roca, or where the nymph’s head would be geographically if her body is in the Tagus, as opposed to Sagres or St. Vincent, where we started the journey. I also think it could mean that the vms was made in Lisbon, there were cartographic and merchant communities in Lisbon at the time that originated from the Mediterranean, and Lisbon was Henry the Navigator’s new home after Sagres as well, new maps of the Portuguese conquests and discoveries were being made at the time of vms creation. I could see such a community as having access to all the best maps and rutters.

Re the gravity idea, i think it is definitely related to concepts about spherical Earth and other such phenomena of our planet.

I think of the nymphs as the spirits of the earthly places they inhabit, not causing anything to happen, per se, but sometimes mnemonically informing us of certain details.

Because it is difficult to get this sort of scholarly background, I thought I’d add the following details.

Until Rich Santacoloma identified the drawing as representing the elements, it was unknown to Voynich studies, as far as I’m aware and to judge from his response when I came to the same conclusion later, neither he nor anyone else thought it had been discovered later.

I identified the drawing as showing five elements, and unlike Rich who thought the fifth was ether, I had concluded that this was (yet another of many) indications of non-Latin character for the manuscript’s content.

When you say, then, “it is often said” what you have seen is plagiarism of Rich’s work, or mine, taken without acknowledgement. I’m happy to have you treat it all again, but it wasn’t “an idea” floating on the wind. It was an opinion first given by Rich (who interpreted it in terms of European thought) and secondly by me – who read the image rather differently.

I do hope this helps. We are all in the same position since someone-or-other decided not only to take and re-use others work without proper recognition for the researcher, but then to conceal their practice by encouraging everyone to co-opt others’ work to their own benefit. I hope no-one does this to yours, and I’ll do what I can, where I can, to inform people who do re-use any original insights of yours where they came from. ‘Blanking’ researchers while taking their work is filthy behaviour imo.

There are certain things in the VMS that are obvious and yet you constantly accuse researchers of plagiarism when they remark on the obvious. The idea that the pipes at the top of the folio might be elements, when one is red and one is poofy and one is grainy and one is spotty is going to be self-evident to many researchers, regardless of whether that person has seen previous research or not.

I don’t mind you filling in readers on Voynich history, as long as you do it accurately.

I DO mind you accusing researchers of plagiarism when they remark on visual features that are self-evident. Researchers independently noting the same possibilities in a specific illustration does not fit the definition of plagiarism.

_____________

Plus, the whole POINT of this blog is to suggest that these may NOT be elements in the Aristotelian sense, but possibly forms of weather. In other words, I am disagreeing with the usual interpretation given by SantaColoma and others, not plagiarizing it.