22 September 2020

A few years ago I noticed something was going on with the plant names in Codex LJS 419, but I was busy with other research, so I bookmarked it for future reference. In March 2020, with most of the world in quarantine, I finally had a few minutes to leaf through the scans and realized, when I saw the peony plant, that the labels had been lightly enciphered.

A Plant Book that Spanned a Century

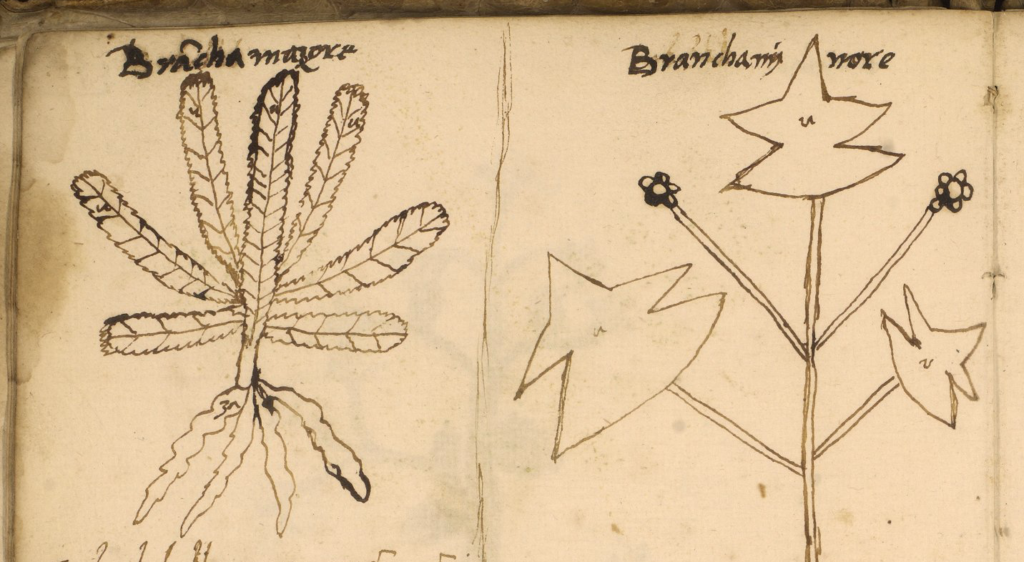

According to the U. Penn Schoenberg Collection Subject Details, the LJS 419 Erbario was begun in the first half of the 15th century with a number of later additions. The drawings are quite good for 15th century. Some are stylized, but most are recognizable.

UPenn Schoenberg Collection LJS 419 is a bit of a pastiche. The drawings are in at least three different styles, and the ones on the recto (the original drawings) are frequently smaller than the ones they face.

There are labels by most of the drawings, and text under some of the images in handwriting that was common to the 16th century. Thus, the text may have been added as much as a century after the drawings.

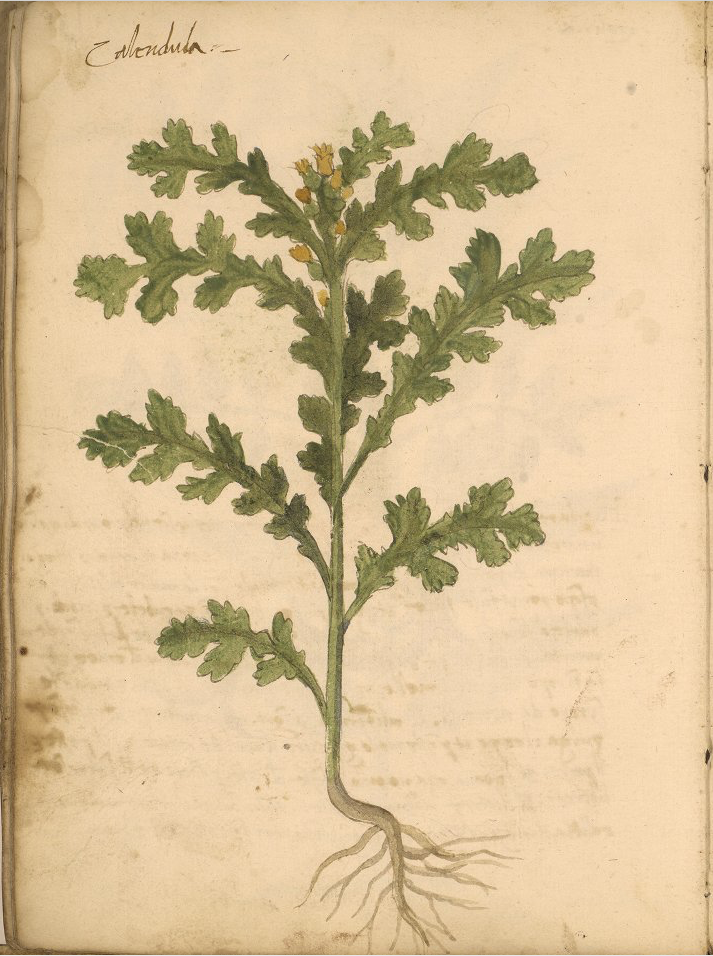

I noticed that some of the labels are incorrect. The plant below is clearly not Calendula, a plant that has had the same name for centuries. It is recognizable as Senecio, probably Senecio vulgaris:

The labels for Pulmonaria (65v) and Salvia (65r) don’t match the plant drawings either, but if you swap the labels, then they match (a detail that the Shoenberg commentator didn’t note in the annotations for each plant).

Most of the labels appear to be correct, however, and they are interesting because some of them are in cipher…

The Garbled Plant Labels

Some of the plant names are readable. Others are oddly spelled and overwritten, like this one:

The word “Latuca” is somewhat mangled. Adding a stem to each “a” makes it Lbtucb. The next word, “agrestis” has a stem through the “e” to make it “f”, and the “i” is “l”.

I wasn’t sure what was happening until I saw an odd label next to a plant that was easy to identify. That’s when I realized this was a simple cipher with some of the vowels changed.

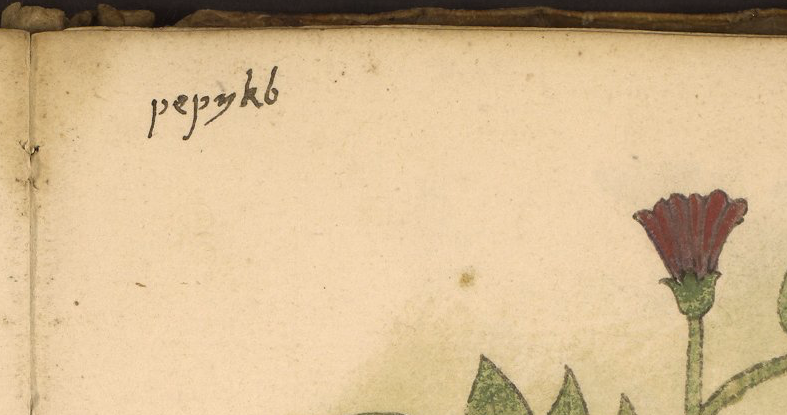

Here is the label. It reads pepnla:

I could see this was a Peony plant not a “Pepnla” plant which, in turn, made it clear that this was a partial substitution cipher. It is sometimes called the monk’s cipher and I can see why. I have often seen it in manuscripts with ecclesiastical content, like sermons.

Notice how the “o” is “p” (I saw the same substitution in some of the earlier plant labels), and the “i” is changed to “l” (ell). That was the clue. It’s a common and simple vowel-substitution cipher that is quite easy to read once you get used to the fact that consonants are used for vowels:

- The “o” is changed to “p” because it is a vowel and “p” is the closest consonant following “o”.

- The “i” has been changed to “l” because it is the closest consonant following “i”. They didn’t have “j” in the Middle Ages (what looks like “j” was usually an embellished “i”) and many languages did not have “k”, so “l” (ell) would be the closest consonant following “i”.

I’m not sure why they left the first “e” and last “a” as vowels rather than substituting all the vowels. Either it was an oversight, or perhaps they thought Pepnla was enough to obscure the name.

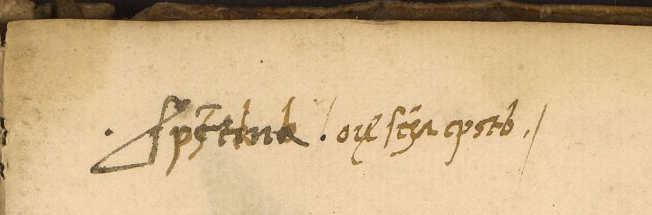

Here’s another example that reveals the order in which things were done for this label but apparently not for all the labels:

Underneath, it looks like Spftlnb, which is a little more difficult to read without decoding it first because it is both abbreviated and enciphered. Someone wrote over it with darker ink, to create S~pe’tina, which is an abbreviation for Serpentina. It uses the same system as the others, of selecting the next-closest consonant to replace the vowel.

Note how the “u” letters in the next two words were written as “x”, which is to be expected for a consonant following “u”. Many languages did not have the letter “w”, and “u” and “v” were roughly equivalent, so “x” is a natural substitute.

Sometimes plaintext is written over the ciphertext. Sometimes it’s the other way around. Perhaps there were three hands involved, one turning it into ciphertext, someone else converting it back.

Now that it was clear that a consistent system was used, it became straightforward to decipher the last word cpstb which was not overwritten. This can be deciphered as “costa”. Costa is a medicinal plant that was common in medieval herbals.

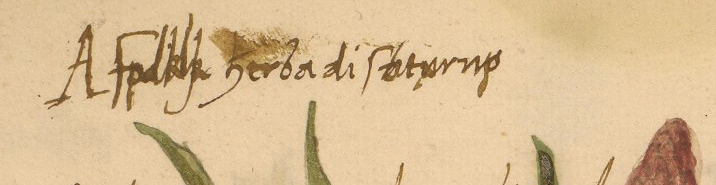

A plant drawing that clearly depicts Asphodel also has an altered label. It looks like this:

Here the ciphered text is Afpdklk, and we can see that the “o” was written as “p” (consistent with the previous examples). The two “i” characters in Afodili (one of the common spellings at the time) were written as “k”.

So the writer apparently did know the letter “k” (“k” was not used in every language but sometimes it was used in loanwords). The phrase following the name “herba di Sbtxrnp” is only partly enciphered. It decrypts to herba di Saturna.

The next label reads Bftpnlchb, which decrypts to Betonicha, another very common plant in medieval herbals:

The next one might have been harder to read without the picture, since it is both abbreviated and enciphered, but it includes a good drawing of the plant:

The word was overwritten as Tprmftlla, which decodes to Torme’tila, with the macron standing for the missing “n” in Tormentila.

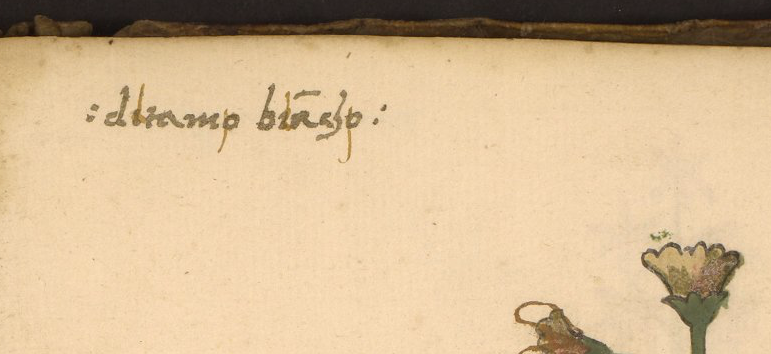

The next one reads dltamp bla’chp, so the “a” was left in its normal state. The plaintext is ditamo biancho. Note the humanist-style “h”, which has a short stem that doesn’t quite reach the baseline. This, in addition to the overall style, is one of the palaeographic clues that the labels were probably added in the later 15th century or, more likely, the 16th century:

Male and Female Plants

The following label puzzled me for a moment. Since pepnkb isn’t a plant name, it has to be the enciphered word peonia. But it doesn’t look as much like a peony as the other drawing already mentioned. It is more upright, and drawn without the seeds. Then I remembered that some medieval manuscripts included both “male” and “female” (mascula, femina) versions of peony, just as they did for Mandrake and a few other plants. Since there is a very recognizable peony drawing on the verso, I’m guessing that it represents the female and the recto represents the male plant:

The next label reads Mprssus dkbbpli, which translates to Morssus diaboli (devil’s bite), a common name for several species of Scabious.

But the drawing is not a Scabious plant. Scabious has pufflike flowers, not bell-shaped flowers. The flower in the drawing is like Campanula, but the hairy stalk and parsley-like leaves are not, so it is probably Pulsatilla, the Pasque flower, rather than Scabious. Most Pulsatilla flowers do not dangle as much as this, they tend to spread their petals, like anemones, but they do sometimes hang, depending on the species. Taken together with the flower shape, leaves, and fibrous base, it’s probably Pulsatilla:

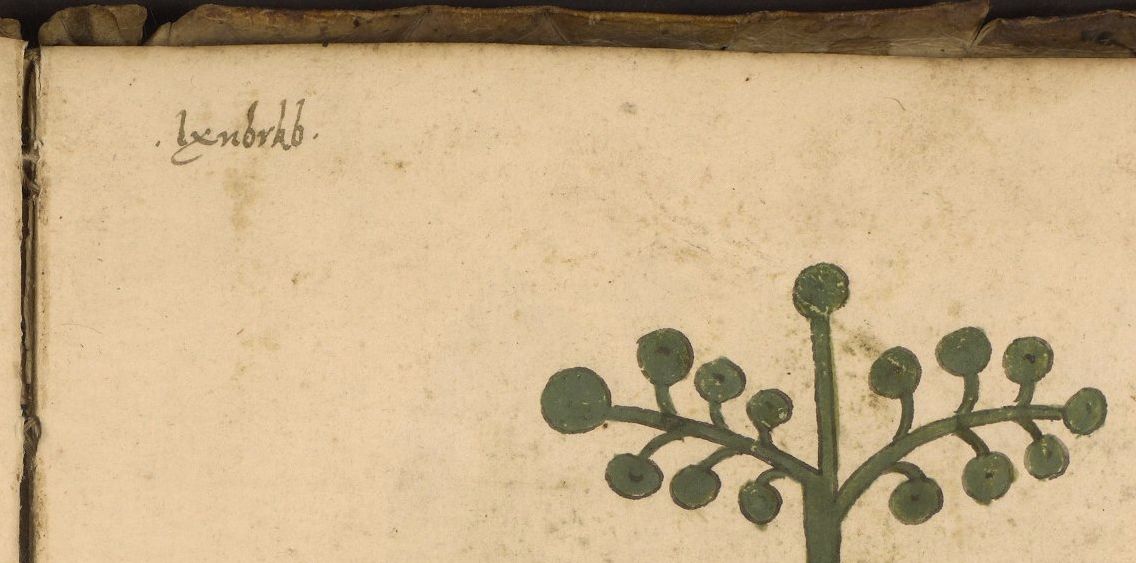

The next label is lxnbrkb, which is described as follows in the Schoenberg annotations for this manuscript:

66: ‘Lenbrkb’ – a puzzle, though the same word is used for a different plant on 71r

It’s really not that puzzling. This decrypts quite easily as “lunaria” by using vowel-for-consonant substitution:

Compared to ciphers of today, or even of 200 years ago, this is easy to read. You don’t even have to make a chart, you just have to learn the letter that follows each vowel and you can read it as though it were normal text.

Other Interesting Details

A few of the drawings are unpainted and include color annotations, a detail that may also exist in the Voynich Mansucript:

Why someone chose such light encipherment for plant names (and only enciphered a few of them) is difficult to understand. Maybe they did it for fun. Maybe they were planning something similar for the rest of the text but never completed the task. What it tells us, however, is that even in the 16th century, these very simple ciphers were still in use, and if you combine them with abbreviations, they can sometimes be a bit more challenging to figure out if there are no drawings to make the meaning clear.

Summary

I had planned to post this blog in April, but simply forgot about it. Then today, I saw the paper of Alisa Gladyseva on Researchgate.net where she describes the peony name in this manuscript as an example of a “corrupted” plant name.

I was quite stunned that someone who writes a paper on the history of cryptography and who claims to have decoded the VMS did not recognize the monk’s cipher (which is simple and only involves partial substitution of vowels) and so I decided to post this blog so the VMS community can compare her interpretation with what is really happening in LJS 419. Here is what Gladyseva wrote in her paper:

Obviously, some names of 13 plants [in MS Aldini 211] seem to be corruptions of known names e.g. ‘Antolla’ for ‘Anthyllis’, ‘Ariola’ for ‘Oriola’. 23 plant names are strongly corrupted for e.g. ‘Metries’ for ‘Myrtus’, ‘Rigogola’ for ‘Galega’….

Manuscript Number is ‘ljs419’ Italy, of XV century is a typical of the medieval Apuleius herbal. But it has corrupted botanical names of plant on 71r folia. As well as the name of plant ‘Pepeko’ 24r, that is probably is one of the species of peony in real. | P E O N I O |. In reason, on the next folia there is another kind of peony: 24v: ‘Peonia’. –Gladyseva, Jan 2020

So, Gladyseva includes a paragraph on corrupted plant names and then cites LJS 419 as an example of corrupted plant names, but it is not! It is an example of a common and very simple medieval substitution cipher, as can be seen by the decryption examples I posted above.

Gladyseva has been claiming for some time that she has deciphered the VMS, but never shows any concrete examples of her method. How could a researcher who claims to have deciphered the Voynich Manuscript in a paper that describes the history of cryptography have missed something so simple and obvious as the monk’s cipher?

I think it’s time for her to reveal her method so the rest of the research community can see if there is sufficient evidence to support her claims.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright September 2020, J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

Interesting to see such a concrete example of a cipher in a herbal manuscript. More often than not, it looks like the real letter was written first and then a line was added to change it into the cipher form. But sometimes the cipher form seems original as well. So someone who intended to write in cipher but forgot sometimes? Or someone who came along later and decided to cipher it up?

Great post, JK, well done! 🙂

One of the talks in the recent Dark Archives conference extensively discussed the same cipher in the context of early mediaeval ciphers. Charles Burnett also wrote at least one paper on it, calling it the “magical alphabet” because of its frequent appearance in charms and other magical recipes.

Thank you, Nick. And thank you for calling my attention to Dark Archives (great name) and Charles Burnett. I was unaware of either one.

Thanks JKP, these are very interesting observations. I wonder what motivated the author to encrypt the plant labels (afterwards). The method is rather simple (if you think about it). In any case it is good to know that something like this exists. I did not know it before.

Thanks JKP! It is really interesting what is the reason of that. It seems it is not unique. Probably the VMs marginalia of the folios f17r and 66r demonstrate the same method. But we still read the overlayed symbols (not all, of course).

To J.K Petersen. Did you notice the encyphered message in the stem of the plant in folio 4?I’ve been studying the manuscript for three years now, many hours a day. It might clarify its content along with some plants you didn’t mention which are the most important. I also have some interesting information about the women section folio 75 and 78. You might contact me. Sorry my English is not perfect.

It don’t think it’s enciphered, Laura. I think it says “rot” (it’s written the same way horizontally in another plant, pointed out by MarcoP). It’s probably German for “red”.

Thanks for your reply. Well I think it says oracle vertically. The first character near the roof is “h” from palmirene or Palestine siriac the following “o” and the “v” Hov in hebrew and if you read horizontally the same combination the first character turns into ‘t’ in our Latin alphabet, o and the last one v Tov in hebrew as well. All in all TOV HOV That means good oracle, good star, good horoscope, good destiny. In modern hebrew TOV is rarely used except when they congratulate just married couples.

Otherwise I love your investigation work about plants is really outstanding.

A question for you. what do you think the stick which the woman in the middle is holding when they are descending the river means? Gerard Cheshire translated it as a stick to measure the depth of the water and he was wrong.

Sorry root instead of roof.