Author Archives: J.K. Petersen

Large Plants – Folio 33v

Voynich Large Plants – Folio 33r

This plant ID was visible for about a week in 2013, but I took it down (along with numerous others), because I was concerned about giving away too much of my research. As with many Voynich newbies, I thought I was on the verge of cracking the VMS. I now know the challenge is much greater than I anticipated.

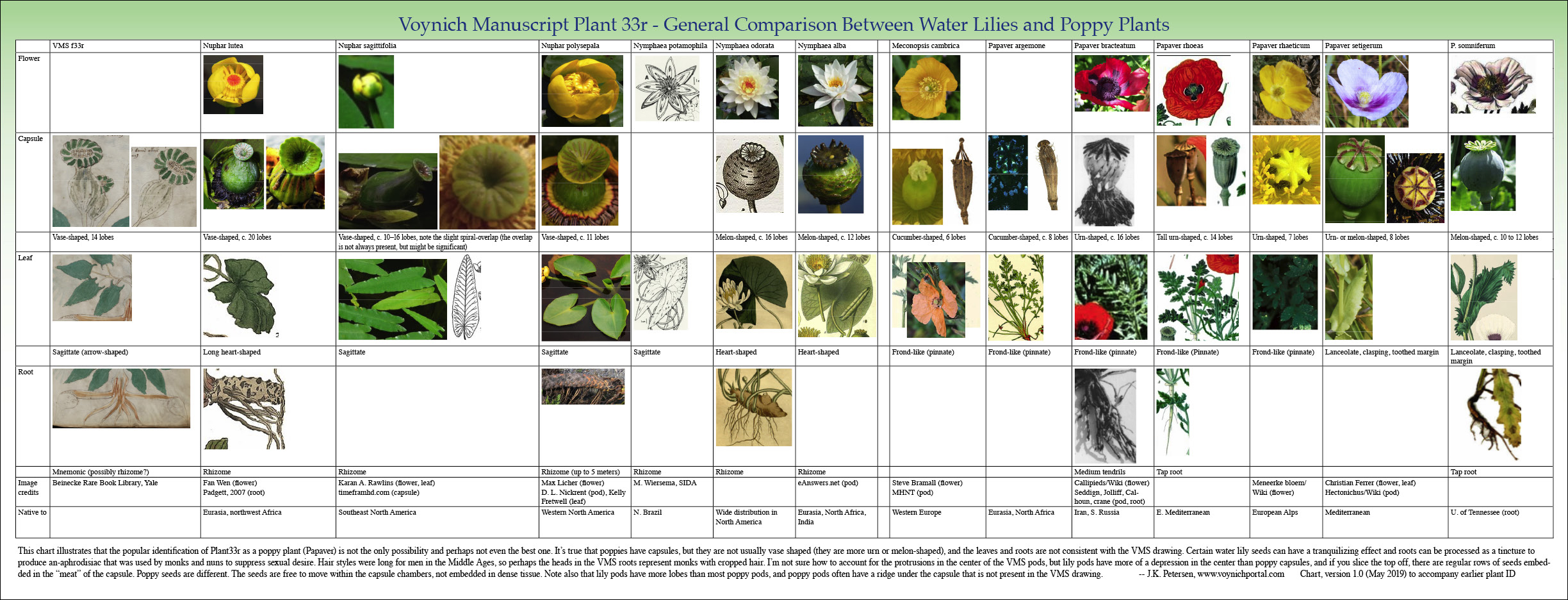

What follows is the original post from 2013, but I have converted the pics to .png and added a May 2019 chart to illustrate my choices because I discovered over the years that my favorite ID has never been mentioned by anyone else. The popular favorite is Papaver (even a Finnish botanist suggested Papaver), but I don’t think it’s Papaver.

As a lone voice crying in the wind, I was worried there might be resistance to my idea if I didn’t add some good illustrations, so I have posted an addendum at the bottom…

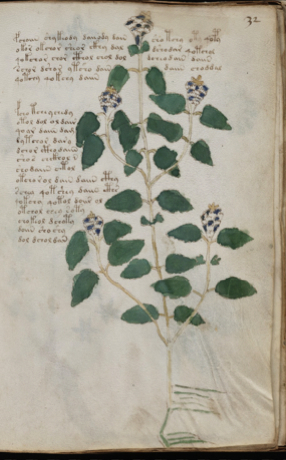

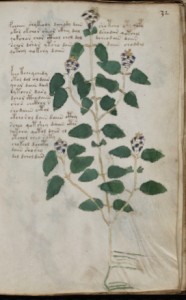

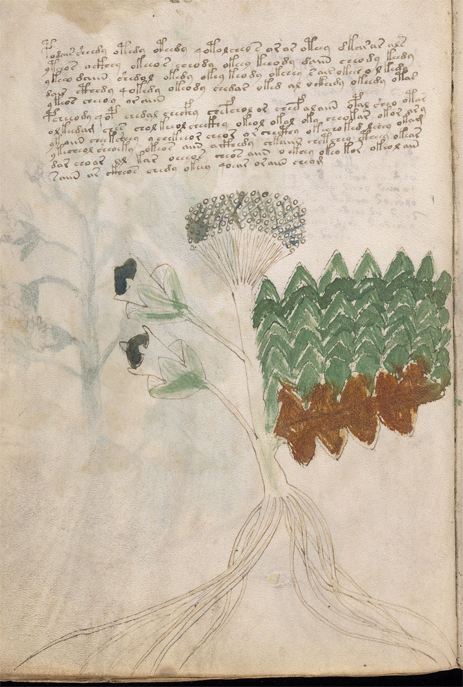

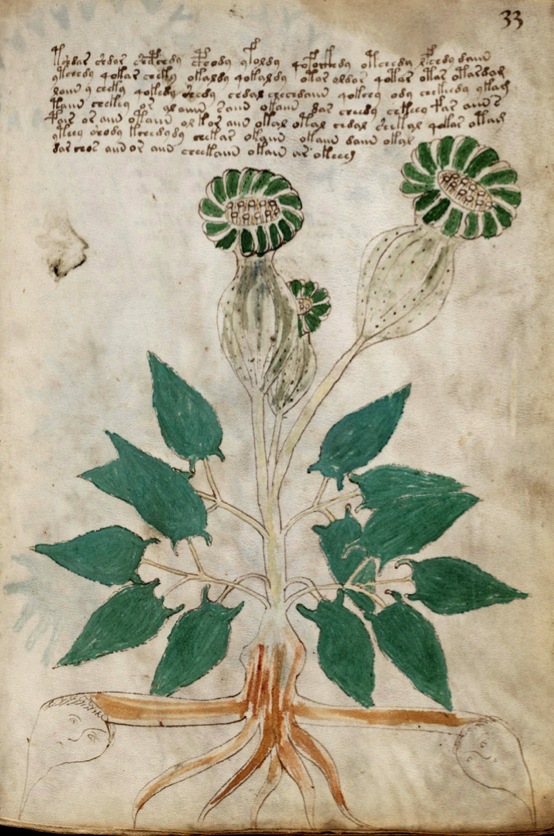

VMS Plant 33r

Plant 33r inhabits most of the space on the folio except for seven lines of text.

Plant 33r inhabits most of the space on the folio except for seven lines of text.

Seed Heads

The plant is topped with slightly rotating rosettes on swollen seed capsules (I might be wrong, but I don’t think they are flowers). There are slight vertical striations in the capsules and dots that might be an indication of texture or shadow. One of the capsules is sightly obscured behind another.

The top of the capsules have been painted in alternating green against the color of the vellum, and the lower portion is lightly washed with a bluish-gray, a color not often seen in the VMS (might it mean that these are dried before use?).

Leaves

The hastate leaves are close to the base and spread around the stem somewhat. They have smooth margins and are painted a fairly solid medium-dark green. Hastate leaves are similar to arrowheads. If the points are exaggerated, then it’s also possible the leaves are sagittate, so I tried to keep both of these shapes in mind when thinking about IDs.

Stems

The stems are moderately sturdy, painted with a very pale wash. They get thinner and branch toward the leaves. A couple of the bottom ones are slightly arched downwards. I wonder if this is an attempt to suggest a rosette of leaves around the stem.

Roots

The roots have a thickened portion in the middle, medium-thick tendrils reaching down and out, and two even-thicker tendrils or rhizomes spreading to the sides and terminating in two heads that look to me like tonsured monks. Hair styles were long in the Middle Ages, so it’s hard to imagine these heads as anything other than monks unless, of course they represent something non-human, like personified moons. If they are moons, they might stand for the name of the plant or the best time to harvest it (during the full moon?). Or maybe the moon is the governing celestial body for the plant. The tendrils are roughly painted a medium brown (not nearly as carefully as the leaves).

Prior IDs

I didn’t look up Prior IDs for this plant because I can only think of two reasonable possibilities and even the second one seems to be a bit of a stretch. Plus, I tend to disagree with existing IDs, so sometimes I’m not motivated to look them up.

Identifying 33r

When I first saw 33r, back in 2007, I noticed the exaggerated seed capsules and immediately thought of poppy. But then I looked at the leaves and roots and changed my mind.

Poppies have very jaggy leaves, and they are not hastate or sagittate. Even the Himalayan poppies don’t have leaves like plant 33r.

If the roots are rhizomes, that doesn’t match poppy either.

On closer inspection, I had doubts about the seed capsules as well.

These weren’t poppy capsules, they were water lily capsules. Probably not Nelumbo species, which have very broad capsules with large seeds that protrude, and very round leaves, but the other species of water lilies, like Nuphar and Nymphea.

Nuphar has distinctly vase-shaped capsules with striations, depressions in the middle of the upper rosette, and leaves that are heart-shaped or sagittate, sometimes like long-arrowheads.

Nuphar grows worldwide, with one of the more common species (Nuphar lutea) having a broad distribution around the Mediterranean and Eurasia. Nuphar has rhizomes (side-growing roots) that stretch to several meters, and the leaves fan out at intervals along the rhizome. I don’t know if Nuphar can have multiple flowers on one stalk, I don’t think I’ve seen that, but the other characteristics of the plant match quite well.

The Problems with Papaver

In contrast to Nuphar and the VMS, poppy plants have a very jagged leaf margin (sometimes clasping), and most of them are frondy, like ferns, not at all like the VMS drawing. The roots are finer, lighter, and usually more vertical than the VMS drawing.

Papaver seedheads are mostly shaped like covered urns, rather than vases, and the number of striations on top is usually less than the VMS, sometimes as few as five. They do not have the depression in the center characteristic of Nuphar and Nymphaea. Many poppy plants have a knob under the capsule, and sometimes a row of holes under the rosette to disperse the seeds when the wind blows. The VMS does not include these details.

Nuphar capsules sometimes have a very slight hint of a spiral overlap in the upper rosette (it’s subtle and it’s not present in all of them). I’ve never seen this in a poppy capsule although they do sometimes have a scalloped edge.

Poppy plants have tap roots, sometimes very thin tap roots, and they are often very light in color. A few species have tendrils, like buttercup roots, but they’re not usually thick as thick as the VMS roots.

What about the Bumps on Top?

One detail that had me wondering was the little bumps on the seed capsule. They’re completely unlike Papaver, but they’re not entirely like Nuphar or Nymphaea, which have a depression in the center. Then I remembered another VMS plant in which the seeds inside a pod had been exaggerated, so I wondered if this was the same idea.

One detail that had me wondering was the little bumps on the seed capsule. They’re completely unlike Papaver, but they’re not entirely like Nuphar or Nymphaea, which have a depression in the center. Then I remembered another VMS plant in which the seeds inside a pod had been exaggerated, so I wondered if this was the same idea.

Nuphar and Nymphaea have very different internal structures to the seed capsules than poppies.

- Poppy is a land plant. The seeds roll around freely inside the capsule chambers and are dispersed by wind when the capsule dries, or they drop off and get stepped on or fall out through the holes near the top, under the edge of the rosette.

- Nuphar and Nymphaea are aquatic plants and the seeds are imbedded in a spongy matrix, rather than rolling around freely. This means if you cut across the top, you will see regular rows of seeds within a lighter medium. As the capsule ripens, it is exposed to water, which erodes it, gradually releasing the seeds (some of them ripen under water). Water lilies aren’t as wind-dependent as the Papavers.

I don’t know if this explains the bumps on the top, I’ll continue to think about it, but it’s one possibility.

And now to the most interesting part…

The Root Heads

I have difficulty explaining the heads if this is Papaver. Why two of them? Most poppies have tap roots, so why wasn’t it drawn with one head and a long narrow root? Why do the thickest roots stretch to the sides? Are they meant to suggest rhizomes that propagate like long snakes under ground or water? If so, they are more similar to water lilies.

I have difficulty explaining the heads if this is Papaver. Why two of them? Most poppies have tap roots, so why wasn’t it drawn with one head and a long narrow root? Why do the thickest roots stretch to the sides? Are they meant to suggest rhizomes that propagate like long snakes under ground or water? If so, they are more similar to water lilies.

Are these monks, as per my original impulse. Or are they moons? What are the pointy parts—are they water droplets with faces? Could this indicate an aquatic plant?

Depending on which source you consult, the moon is said to be the ruling body for both poppies and water lilies. A water lily picked on the full moon was used in spells to attract a lover, but this is in recent writings, and I haven’t been able to confirm if this accurately reflects a medieval spell.

Maybe the roots have some other meaning. Various parts of water lilies are eaten, and some have sedative or narcotic effects. Monks and nuns used them to suppress their sexual desires. When prepared as an alcohol tincture, they were an-aphrodisiacs. Could this account for the heads with shorn tresses? Are they tonsured monks?

Summary

Plant 33r is not a perfect match for water lilies. It’s close, much closer than Papaver, but why would the points on the leaves be exaggerated, and why are there bumps in the tops? Is it a really bad drawing of poppy?

Are there other explanations for the heads besides monks or moons or water droplets? I’m still mulling this over, but for now, the best ID I have is one of the Nuphars or Nymphaeas, both of which are widespread and well-known in the Middle Ages.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2013 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

Postscript 12 May 2019:

To make the similarities and differences between these plants more clear, I created a chart with a few samples (click to see it full-sized):

Large Plants – Folio 32v

Large Plants – Folio 32r

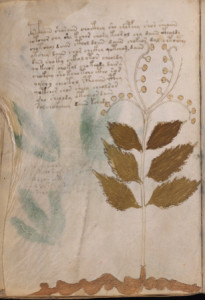

Plant 32r is an upright plant occupying a large portion of the page from bottom to top, interwoven with what appear to be two main blocks of text. The top “block” (assuming the lines on the left are associated with those on the right) is broken across the top of the plant.

The main plant colors are green leaves, brownish stems and blossoms, and alternating blue and clear for the scaly portion holding the blossoms.

The colors are somewhat crudely (hastily? impatiently?) applied but stay mostly within the lines. The blue, in particular, is “dabbed” with less concern for maintaining shape. This does not appear to be because of the space limitation since the blossoms, which are equally small, are more carefully rendered. Perhaps the blue pigment was drier and harder to spread smoothly.

Details

Leaves: Opposite, roughly between elliptical, cordate and deltate. There are smaller, somewhat irregular pairs under some of the larger leaves. The petioles are fairly short. The margins are serrated or irregular.

Flowers: Scaly/overlapping flower head, with a blossom protruding from the end that might have roughly three petals (or three petals visible from one side or may be trumpet-shaped).

Stems: Slender and regularly branching. Plant 32r shows a strong overall symmetry.

Roots: There appears to be a tap root with fine rather than thick tendrils, possibly asymmetric, or perhaps directional (more about this below). Most VM 408 plants are rendered in brown or brick red.

Prior Identification

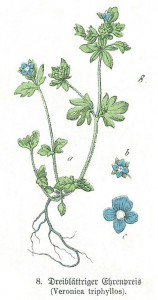

Edith Sherwood has identified this as Speedwell (Veronica triphyllos), but V. triphyllos differs from Plant 32 in a number of ways:

- V. triphyllos has small roughly palmate (somewhat digitate) leaf pairs at regular intervals along the stem (see illustration below), they are not the larger more elliptical/deltate leaves of Plant 32r.

- V. triphyllos blossoms don’t emerge out of a scaly head in the same manner as 324. There are sometimes clusters of leaves at the end of V. triphyllos stems, but the parts of the cluster are more distinctly separate and pointed than the heads of Plant 32r.

- The branching stems are not as symmetric as 32r.

- The pistils of V. triphyllos blossoms are quite prominent and might perhaps have been included by the VM illustrator.

- V. triphyllos stems and leaves are hairy and this too might have been included if the illustrator were trying to represent V. triphyllos.

I don’t see V. triphyllos as a good match for Plant 32r.

The palmate, somewhat digitate, leaves of Veronica triphyllos are distinctly different from Plant 32r. V. triphyllos is not as symmetrically branched as Plant 32r. The flower heads of V. triphyllos are more discrete and separate than the scaly heads of 32r.

Other Possibilities

Examples of possibile candidates for Plant 32r that more closely resemble the VM plant include the following:

Melampyrum cristatum (left) doesn’t appear to be close enough for consideration. The “scaly” section has long protruding tips and the leaves are too narrow but the pipe-shaped blossoms emerging from the end, the evenly branching stems and opposite leaf arrangement caught my eye. Melampyrum nemorosum (second left) has wider leaves but a more spiked and upright appearance.

Coridothymus capitatus is a medicinal plant mentioned in manuscripts like Materia Medica but the leaves are very small and not branched in the same way as 32r, and the blossoms at the tip of the flower head are more numerous than Plant 32r.

Thymus moroderi and Thymus serpyllum (middle right) are similar in structure to 32r, but the leaves are much smaller in proportion to the flower heads.

The Indian plant, Strobilanthes callosus, has some of the characteristics of 32r, but the blossoms are larger and are more numerous along the stems and the “scaliness” is not as prominent. Strobilanthes nutans is tempting, it has trumpet-shaped blossoms emerging from scaly flower heads and more closely matches 32r than S. callosus, but the branches tend to trail and the flower-heads to nod, while the Voynich plant appears to be upright. Strobilanthes dyerianus is more upright, but the blossoms protrude much farther than Plant 32r blossoms.

Possible Closer Matches

Agastache foeniculum (Anise Hyssop) and Agastache rugosa have longer, bushier flower heads and more pointed leaves than 32r. Agaste urticifolia (left, courtesy of Dcrjsr, Creative Commons), is a fairly close match for the 32r leaves, but it has more plume-like flower heads.

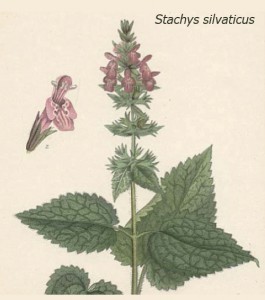

Stachys silvaticus (Hedge Woundwort, right) might be considered, it fits the overall proportions better than the previous examples. However, the leaves and flower heads are more tiered than the single flower head of 32r.

Plants of the mint family (Mentha), tend to have bushier flower heads than 32r and they rise in a tall spike, sometimes with several tiers. The leaf tips are a little more pointed than 32r.

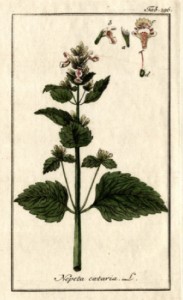

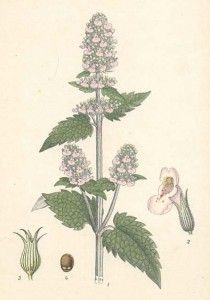

The blossoms of Nepeta cataria (Catmint, second right) tend to be more numerous than 32r but N. cataria might be worthy of consideration.

The Flower Heads

As far as matching the 32r flower head, lavender appears to be closer than most of the above.

Lavender (middle) has flower heads simlar to 32r, with scaly, overlapping protrusions, and darker smaller blossoms within some of the “scales” and, in some varieties, like French lavender (right, Blackwell 1730s), a single larger blossom emerging from the end. However, the leaves are very narrow and linear, and not as distinctly opposite, compared to Plant 32r. The heads are a good match—the leaves are not.

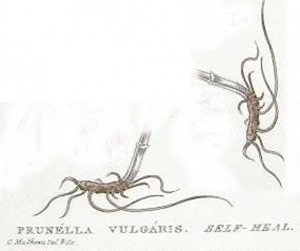

Which brings us to Prunella vulgaris, also known as Self-Heal—a plant with significant stature as a medicinal plant in the Middle Ages.

The leaf shape and general leaf-and-stem arrangement of P. vulgaris are a better match for Plant 32r, as are the scaled flower heads with protruding blossoms at the ends of the stems. The antique botanical print on the right shows tiny extra leaves reminiscent of the small leaves or bracts in Plant 32r. The distinction between the tiny florets within the “scales” and the end blossom is not as distinct as in the Blackwell French lavender illustration shown earlier, but overall, 32r is closer to Prunella or Catmint than to lavender.

Prunella (Self-Heal) is not an assured identification, but it is a step in the right direction and is a much closer match to 32r than Veronica triphyllos. Oddly, on a related note, Sherwood has identified Plant 14v as Stachys monnieri (Lamb’s Ear, Alpine Betony) even though the Voynich plant, 14v, is shown with large, heavily serrated, almost frond-like leaves, and S. monnieri has heads and leaves similar to Prunella. S. monnieri does have larger and more deeply serrated leaves, but even so, it is closer to 32r in general proportion of flowers to leaves than Plant 14v.

Roots

Also, as a point of interest, some of the old botanical illustrations (e.g., W. Baxter, 1837) show Prunella roots in a sideways orientation (left) and since the root tendrils come out of the root going down, it sometimes looks asymmetric like 32r (imagine it turned 90° as in the example in the middle so that it streams out of the main root to one side). This might be a stretch, to try to justify the arrangement of 32r roots but it’s something to think about. Some plants propagate by sending out root shoots to the side under the ground and perhaps this was the Voynich illustrator’s way of symbolizing it.

Summary

The above examples are not exhaustive. Each of the aforementioned plants may have relatives that more closely match Plant 32r and likely candidates from other species have been omitted for the sake of brevity, but it charts a path, based on details of the VM plant, to some of the more likely possibilities and explains why Sherwood’s choice of Veronica triphyllos seems unlikely.

Plant 32r Veronica triphyllos (Sherwood) Catmint Prunella

This is not a definitive identification but, for now, I’m leaning toward Prunella or one of its relatives as the inspiration for Plant 32r.

Posted by J.K. Petersen

Addendum: I’m not sure how the links to all the pictures disappeared (the pics were still visible in edit mode) but I have done my best to restore them to the originals. The article doesn’t make sense without them.

Voynich Large Plants – Folio 31v

This is not one of the plant IDs I uploaded in 2013. I couldn’t decide whether the pose of the plant was symbolic or naturalistic and was hesitant to post it. My original ID assumed a literal expression of certain characteristics of the plant which I see as pinnate leaves, asymmetric flowers, and possibly a clumpy seedhead.

Nine years have passed since my initial assessment of the plant and I still haven’t figured out whether this plant is naturalistic or symbolic. Is it a symmetrical plant that has been rearranged to look like an angel or other symbolic shape? Or is it an asymmetric plant? So much time has passed without an answer, I have decided to post my original (naturalistic) ID as I continue to search for symbolic interpretations.

Plant 31v is a markedly asymmetric drawing. It’s not unusual for plants to have asymmetric flowers, but asymmetric leaves are less common and those with asymmetric lobed leaves quite rare.

The two branches on the left might be closeups of the flowers or the seedheads. The clump at the top might indicate the growth habit of the flowers or seeds, which may appear as a tight clump.

The leaves are distinctive. Besides the jaggy lobes, the closest one is brown and the rest green. Plants with mostly green leaves sometimes have some that turn red or brown long before the others, so this can sometimes help identify a plant, but one has to look at all the plant’s attributes before deciding what the two tones might mean.

The roots are very long and slender and have been left unpainted, as has most of the stalk. The flowers or seeds are painted blue but the VMS palette is limited and blue has been chosen for many of the flowerheads, particularly those that look like they might be seeds, so it may not represent the color of the flowers.

Prior Identifications

Edith Sherwood has identified 31v as Valerian. I’ll agree that the roots are a good match, but I don’t think it’s the most likely ID. The VMS leaves do not resemble Valerian, which is more feathery. As I posted in 2013, I think it’s more likely that Plant 90r is Valerian (Phu). Plant 31v is probably something else.

Edith Sherwood has identified 31v as Valerian. I’ll agree that the roots are a good match, but I don’t think it’s the most likely ID. The VMS leaves do not resemble Valerian, which is more feathery. As I posted in 2013, I think it’s more likely that Plant 90r is Valerian (Phu). Plant 31v is probably something else.

Other Possibilities

Based on the leaves, it occurred to me that this might be a thistle or Acanthus plant, or perhaps even one of the many dandelions or hawkweeds, but the VMS flowers or seedheads differ in some important ways from thistles and asters. The same is true of Pedicularis, Gerbera linnaei, Sonchus congestus, or Hyoseris—the leaves match moderately well, but the flowers don’t.

Narrowing it down to plants that fit as many features of the VMS drawing as possible, I ended up with two that stood out more than others—one is inherently asymmetric and the other matches the VMS plant fairly well while suggesting asymmetry in another way…

Limonium sinuatum (Statice sinuata)

Limonium sinuatum is a Mediterranean plant with lobed (pinnatifid) leaves that match fairly well to the VMS. They are similar in shape to dandelion leaves. The flowers are asymmetric but the florets sometimes clump into masses so thick they look almost like rounded puffs, which might explain the two kinds of “flowers” in the drawings. Like the VMS, the tendril-like roots are stringy:

Despite the similarities, I wasn’t completely satisfied with this ID… the leaves of Limonium sinuatum are symmetric and I couldn’t find any references to angels or other anthropomorphic symbols that might explain the asymmetry or human-like pose of the VMS drawing.

Was there a plant that matched the VMS plant more closely?

Potamogeton crispus

There is a widespread Mediterranean/Eurasian pondweed that might explain the asymmetry of the VMS drawing. It’s called Potamogeton crispus, a plant with distinctively lobed and rippled leaves that are green or brown and sometimes both green and brown. In fact, the lobes and brownish color are distinguishing characteristics.

There is a widespread Mediterranean/Eurasian pondweed that might explain the asymmetry of the VMS drawing. It’s called Potamogeton crispus, a plant with distinctively lobed and rippled leaves that are green or brown and sometimes both green and brown. In fact, the lobes and brownish color are distinguishing characteristics.

Another interesting characteristic of this pond-weed is the two kinds of stalks, one with small individual knobs, the other with clumps (see below). The clumps are not as thick as those in the VMS drawing, but this duality might help explain the way the VMS plant is drawn. If it’s not intended to be Potamogeton, perhaps it’s a similar plant with dual stalks.

Like the VMS drawing, the stems of Potamogeton crispus are quite a bit lighter than the leaves, and the rhizomes long and slender.

But what about asymmetry? Potamogeton crispus is not an inherently asymmetrical plant but pond plants sway with the movement of the water and will often look asymmetric as parts of the plant are pushed farther from the others. A stronger current can cause leaves to orient in one direction, sometimes forming clumps. All these characteristics may be found in the 31v drawing.

Are you skeptical that an aquatic plant might be in the VMS?

Aquatic plants, and plants that stand in water for parts of the year, are very well represented in medieval herbals. Duckweed is often included, as are Nuphar and Nenuphar, Mentha Aquatica, Caltha palustris, Sagittaria, Acorus, Petasites, Bistorta, Alisma, Equisetum, buckbean, Polygonum, frogbit, water-cress, sedge, Cyperus, and Veronica. Sometimes one finds Villarsia. Even seaweed is sometimes represented.

Summary

I’m not as confident about these IDs as I am about some of the others, but I think they should be considered and I haven’t seen anyone else suggest Limonium sinuatum or Potamogeton crispus as possibiities for 31v, so regardless of whether they stand the test of time, I thought it was important to give them due consideration.

J.K. Petersen

Copyright © 2018 March 17, All Rights Reserved

Large Plants – Folio 31r

Voynich Large Plants – Folio 30v

Introduction

I have a particular reason for uploading this information ahead many of the other Voynich-plant articles that are sitting on my hard-drive. I have not spent extensive time looking at other Voynich sites (very little actually) but it’s impossible to look up pictures of plants without Edith Sherwood’s name showing up in the search. Her plant pages have been online for many years and thus have filtered into the blogosphere to the point where it’s almost impossible to not see them and many of the identifications, like this one, take me by surprise.

Sherwood has identified Voynich Folio 30v as a plant named dodder.

First let me make it clear that I am not a botanist. I like plants but have no time to garden or to study the correct technical terms for their parts. I understand that the colored part of a plant that looks like petals is not always a petal, it’s sometimes an extended bract or calyx, sometimes it’s a colored leaf, but that’s as far as my botanical knowledge goes. Nevertheless, despite this lack of background or training in botany, I think I can say, with considerable confidence, that this plant is not dodder. First I’ll describe the Voynich drawing and then I’ll explain my reasons for rejecting Sherwood’s identification.

Description

Folio 30v features a plant that covers most of the page from bottom to top. It has an erect stem that is left unpainted except for the part that connects to the roots. Along the stem are three sets of opposite elliptical leaves. The leaves are distinctly serrated, perhaps even toothed, and have been colored a greenish-brown. Unlike many of the VM plants, the veins have not been included, so it’s impossible to know if they are parallel or, more commonly, have veinlets that extend out from a central vein.

Folio 30v features a plant that covers most of the page from bottom to top. It has an erect stem that is left unpainted except for the part that connects to the roots. Along the stem are three sets of opposite elliptical leaves. The leaves are distinctly serrated, perhaps even toothed, and have been colored a greenish-brown. Unlike many of the VM plants, the veins have not been included, so it’s impossible to know if they are parallel or, more commonly, have veinlets that extend out from a central vein.

Above the leaves, the stem branches into four curving stalks that have evenly-spaced berry-like structures with a dot in the middle. The very tips of the upper stalks include a curved leaf-like endpoint that extends past the last “berry.”

The upper part of the stalk is embellished with long delicate lines that resemble hairs and between the pairs of “berry” stalks on each side is a feathery extension with asymmetric “hairs.” Whether these are left-over branches from a previous year (or a previous blooming in the same year), a differentiated structure, or something else, is not clear from the drawing.

The roots are distinctive— long wiggly rhizomes extending off the page on both sides. They are painted a brown color but not quite the same greenish-brown as the leaves.

The text occupies three lines across the top and wraps along the lefthand side of the plant for another eight lines, brushing the edge of the plant in four spots.

Prior Identifications

As mentioned, Sherwood claims this VM drawing represents Cuscuta europeaea, known as dodder. Dodder is a common plant growing in many parts of the world. I’ve seen it on some of my hikes, without knowing its name.

The first time I noticed dodder, many years ago, the twining string-like stem had a vertical strangle-hold on a pair of wetland plants growing by a slow-moving creek. Slender tendrils snaked around the tangle of stems, binding the two plants together in a lover’s knot, with intermittent puffs of pale flower clusters serving as the nuptial bouquets.

As sinister as it was lovely, the twining dodder had no leaves of its own, preferring to parasitize the plants it so tightly binds together.

The picture on the left, which I added the day I uploaded this blog, shows the twining tendrils, courtesy of Wikipedia, and I discovered from the wiki that dodder goes by names such as hellbine, devil’s guts, strangleweed, and witch’s hair and that it does, in fact, have leaves, but the vestigial structures are little more than tiny scales. Without significant leaves or chlorophyl, it cannot draw energy from the sun in the same way as other plants and makes up for this by pushing sharp little “suckers” into the host plants to vampirize their nutrients.

So why would Sherwood identify the Voynich plant as dodder? As far as I can see, they have nothing in common. Dodder is a virtually leafless vine with intermittent flower clusters and, once it insinuates its suckers into another plant, it sheds its roots. In contrast, the VM plant is an erect plant topped with long rows of berry-like structures, with showy, serrated, elliptical leaves, and burly, long roots. As far as I can see, dodder and the VM plant have nothing in common.

So putting aside the obvious misidentification, is it possible to provide a better ID for VM 30v than given by Sherwood?

Possible Identifications

Poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), a plant well-known in North America, has serrated elliptical leaves, substantial roots, and long stalks with white berries that have a dot in the center like VM 30v. When heavy with berries, the stalks droop and curve like the VM plant, but they tend to cluster at the nodes rather than extending from the apex of the plant. The leaves, unlike the Voynich plant, are trifoliate.

Another plant that closely resembles the “berry” stalks of VM 30v is poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix). It has long spindly stems holding round white berries with a small black dot in the center. They are not expressly one-sided on the stem as in the Voynich plant, but they do sometimes have more berries on one side than the other. The sumac has elliptical leaves but they are not distinctly serrated and they are trifoliate at the ends of the branches. The “berries” are a good match, but the rest of the plant is less so.

Baneberry (Actaea) also resembles VM 30v in that it has long stocks with red or white berries with a black dot in the middle, serrated elliptical leaves and, in the case of red baneberry, hairs along the stems under the berries. Like Poison ivy and poison sumac (and unlike VM 30v), Actaea leaves have a trifoliate or odd-pinnate arrangement, depending on the species.

Perhaps a better candidate for VM 30v is dog’s mercury (Mercurialis perennis), a European plant with elliptical serrated leaves, substantial roots, and numerous tall spindly stalks studded with berry-like green seed-heads. The roots are somewhat thick and numerous and do have long rhizomes extending out to the sides. What is especially interesting about Mercurialis is that if you flatten it into a herbarium specimen, it more closely resembles the VM plant and, when it blooms, has hair-like stamens that are perhaps represented by the delicate structures between the stalks. It’s also possible the more delicate stalks represent the male plant, with the berries representing the female. A less common species, Mercurialis ambigua, has both male and female structures on the same plant.

Where Mercurialis differs significantly from VM drawing is in the shape of the fruits. The VM “berries” are distinctly round with a central dot, whereas dog’s mercury is somewhat triangular and arranged in clumps. Even the closely related Mercurialis annua (which has rounder “berries”) forms clumps rather than discrete berries that are covered with hair-like protrusions. The VM “berries” are smooth.

There’s one more plant that might be considered. Like Mercurialis, it’s not a perfect match, but it does have some interesting similarities.

There’s one more plant that might be considered. Like Mercurialis, it’s not a perfect match, but it does have some interesting similarities.

VM 30v has leaves that are very distinctly opposite and Circaea lutetiana (enchanter’s nightshade) has this characteristic, as well. The base of C. lutetiana‘s leaves are slightly more rounded than the VM plant, and it doesn’t generally have such deep serrations, but it does have branched fruiting stems that often branch in groups of three, but typically vary from two to four.

There are numerous roundish fruiting bodies along each top-stem and the ones near the base tend to be more asymmetric than the ones near the top. Where they differ from the VM plant is in their shape, which is more teardropped, and they don’t have a distinctive dot at the end of each “fruit”. I suppose the round shape might not be a fruit at all—if it were the bud before the flower opens, there is a small light spot at the end of each one, but the shape of the bud is more oval than round. Also, assuming the VM plant is drawn somewhat to scale, C. lutetiana‘s seedheads are not as large as VM 30v, relative to the stem. Another significant difference is that C. lutetiana‘s fruits are quite woolly, whereas the VM 30v drawing doesn’t have this characteristic, except on the stem. Was the VM illlustrator trying to express the hairy aspect of a plant without putting in each hair? The roots of C. lutetiana somewhat resemble the VM plant but lean more toward being a tap root.

If you were to take dog’s mercury and enchanter’s nightshade and merge them, you might get something similar to VM 30v but neither one, by itself, completely fits the bill, which means there may be a plant that resembles it more closely or the features of the plant are drawn less accurately than one would hope.

The alternatives mentioned here may not entirely match VM 30v but I think it can be said without hesitation that the VM drawing does not, in any way, resemble dodder.

Posted by J.K. Petersen