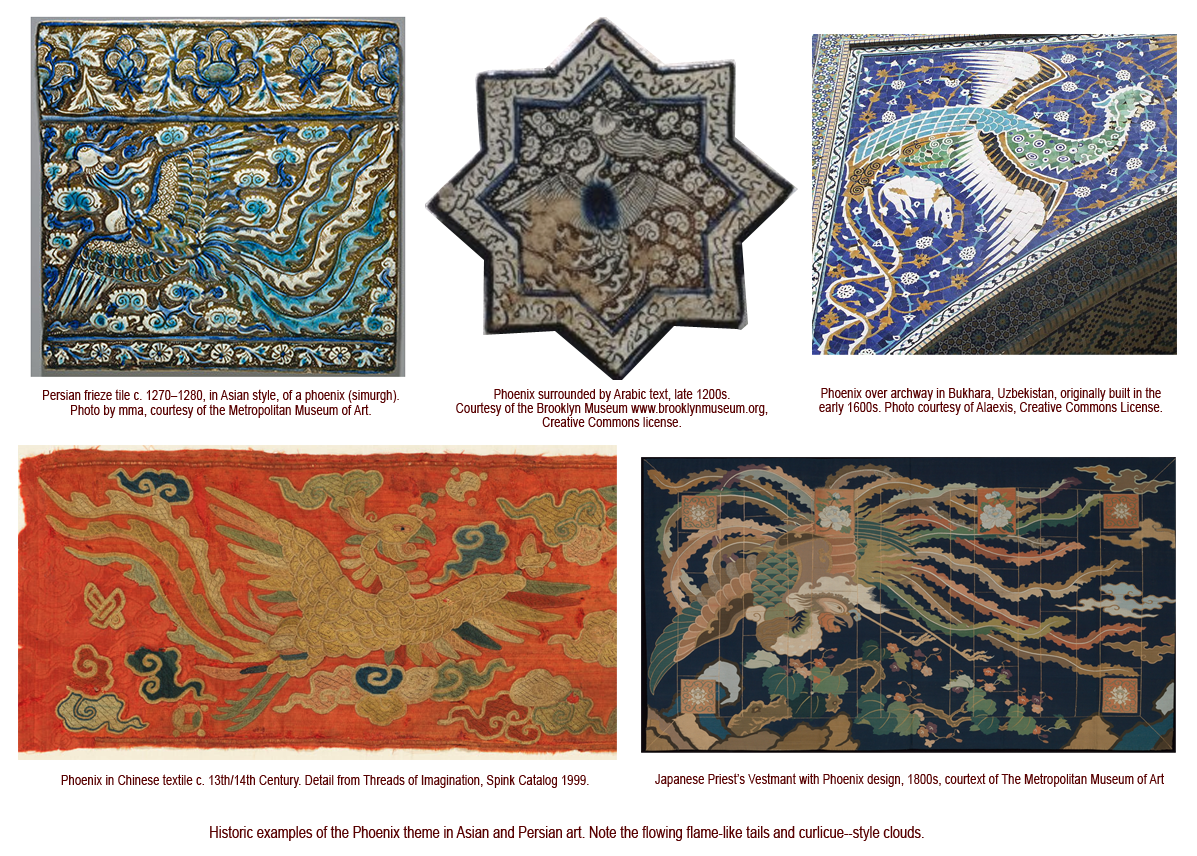

In a previous blog, I illustrated some of the Asian stylistic conventions that influenced Persian art in the middle ages, with dragon and phoenix imagery as examples. A while later, it occurred to me that someone reading the blog might get the misimpression that the phoenix itself had been inherited from east Asian art, but that is not that case. Persian culture was already rich with “phoenix/firebird” legends prior to the infusion of Asian illustrative traditions.

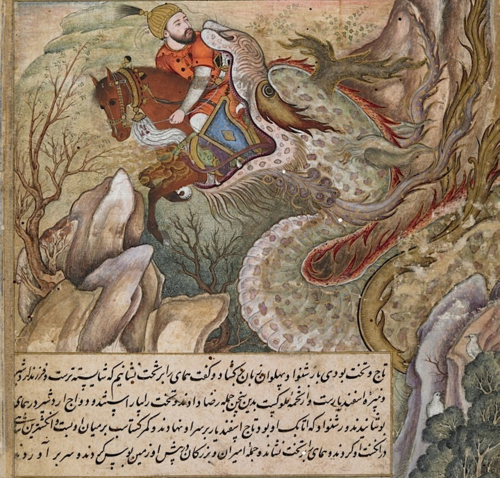

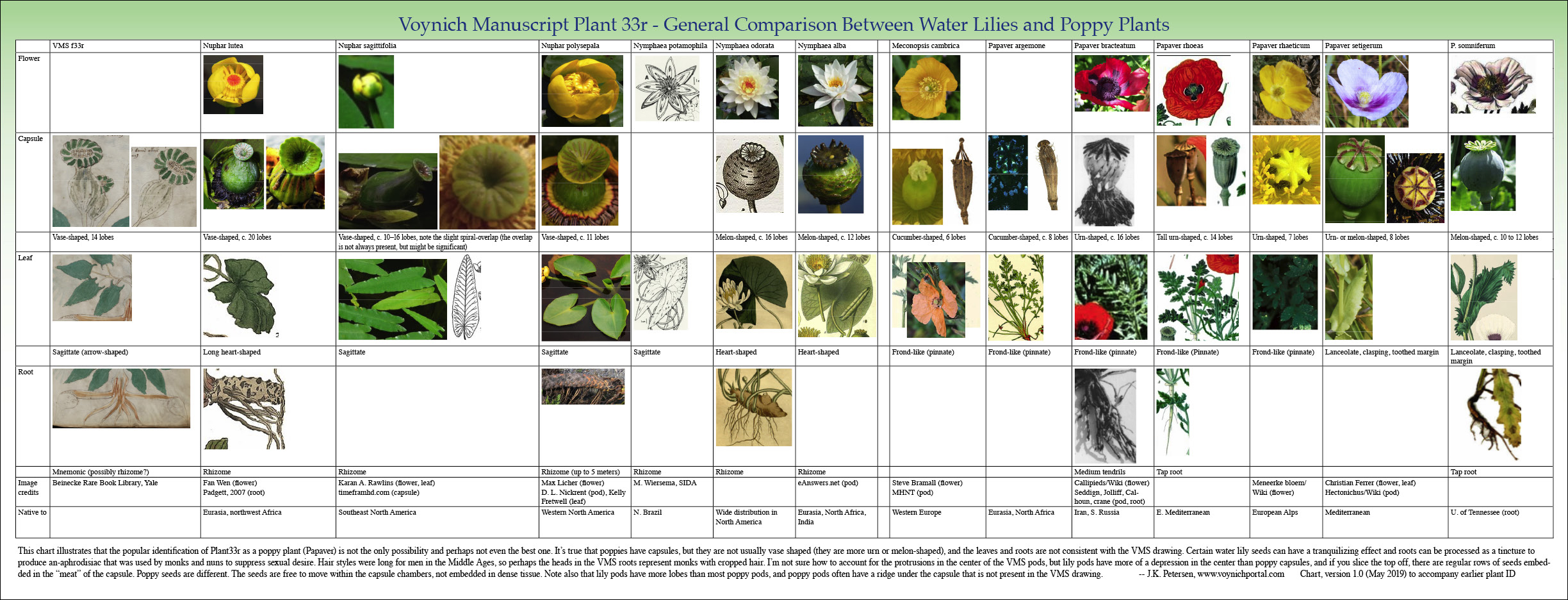

The Simurgh is a mythical bird that greatly resembles the east Asian phoenix except that it was originally drawn with a lion’s face and forepaws. In most respects, however, it would be mistaken for a phoenix by anyone not familiar with Arabic script or ancient Persian culture and, indeed, the two became almost indistinguishable after Asian drawing styles and myths were absorbed into Persian art, as is illustrated by this 17th century example:

In Isfandiyâr’s fifth trial in the Book of Kings (1616), he battles the simurgh with a well-aimed swipe to the neck. In the same manuscript, the simurgh is present at the birth of Rustam,legendary hero-to-be, who teams up with the simurgh to defeat Isfandiyâr. [Image courtesy of NYPL Spencer Coll. Pers. MS 3.]

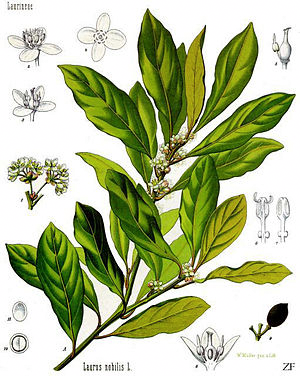

This Sassanid silver plate has a bird-like version of the symurgh motif that was popular from around the 7th to 10th centuries:

This Sassanid silver plate has a bird-like version of the symurgh motif that was popular from around the 7th to 10th centuries:

This birdlike simurgh retains very little of the lion shape other than the forepaws, and includes a more extravagant tail similar to later expressions of phoenix imagery. [Photo credit: Reza Abbasi Museum, Tehran.]

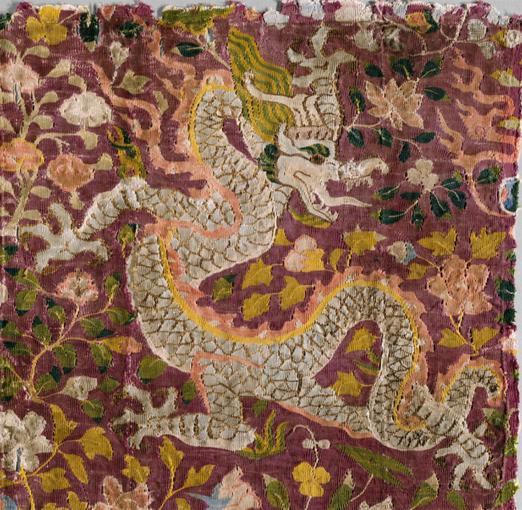

Silk fabric featuring two simurghs facing one another with a tree (possibly the tree of life) between them. [Image credit:Tehran National Museum photo by Fabien Dany – www.fabiendany.com]

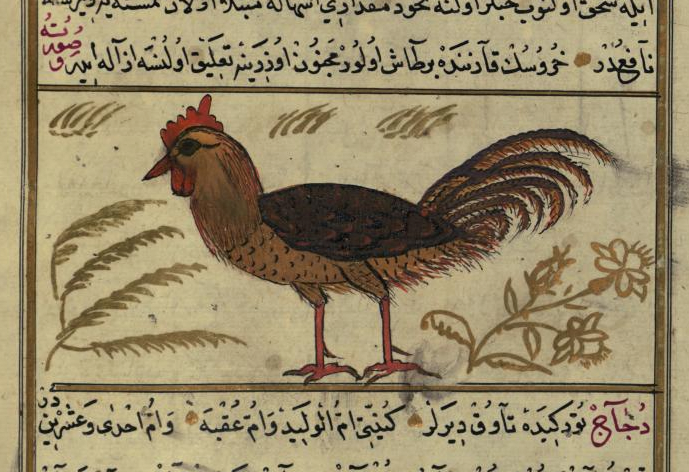

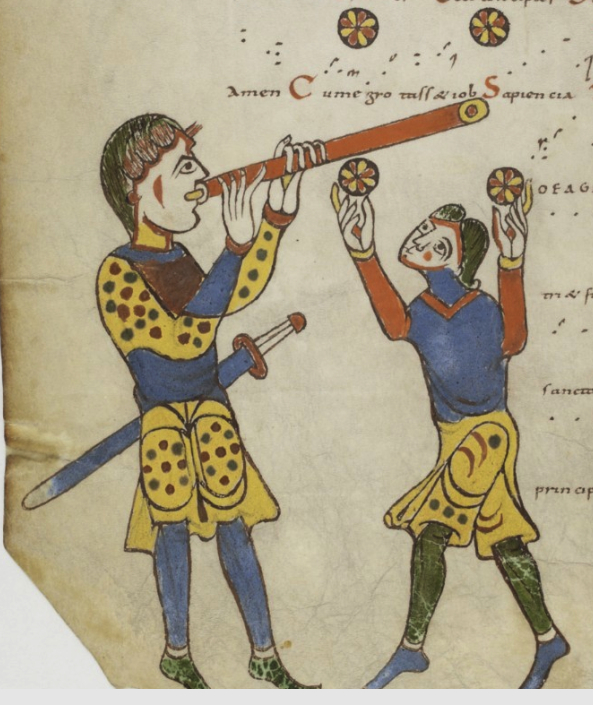

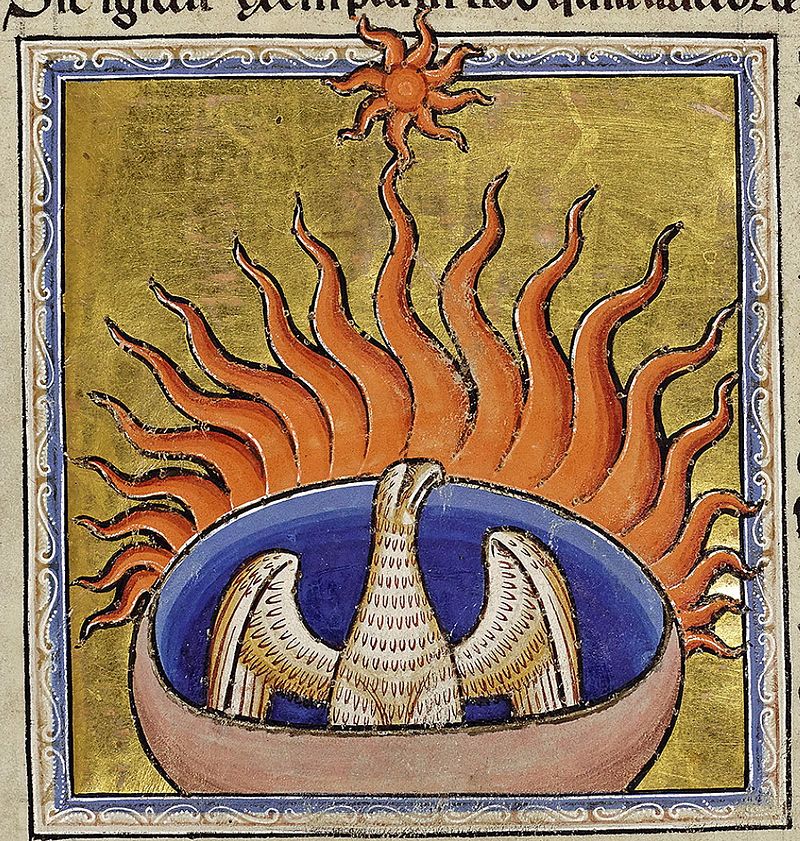

This 13th-century image from the Aberdeen Bestiary, resembles the earlier raptor-like versions of the simurgh more than the eastern phoenix or later Persian simurghs:

In the Aberdeen Bestiary, from about 1200, a raptor-like phoenix sits in a container that it has created with aromatic substances such as frankincense and myrrh. It looks toward the sun and fans the flames that will soon consume it. This hawk or eagle form of phoenix is more similar to the earlier Persian simurghs than later ones that show far-Asian influence. [Image credit: Aberdeen Univ Lib. MS 24.]

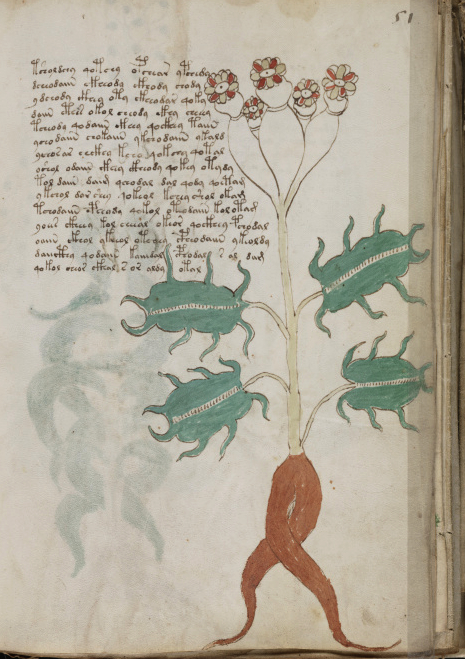

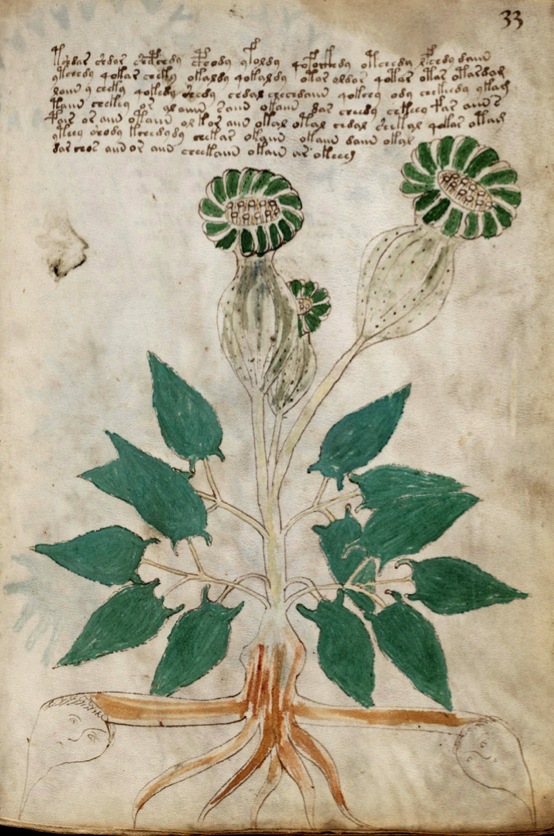

It’s difficult to know how long the tree-of-life and harvest associations with the simurgh were retained, as the simurgh was constantly evolving, but there is a perplexing image in the Voynich Manuscript in which a creature that looks like a bird sits in a nest (or some kind of container) on a precipitous tor. Next to the bird is a tree-like structure that might be a tree, bush, or perhaps stalks of grain. It’s difficult to tell because many medieval drawings of trees are rather twig or grain-like.

It’s difficult to know how long the tree-of-life and harvest associations with the simurgh were retained, as the simurgh was constantly evolving, but there is a perplexing image in the Voynich Manuscript in which a creature that looks like a bird sits in a nest (or some kind of container) on a precipitous tor. Next to the bird is a tree-like structure that might be a tree, bush, or perhaps stalks of grain. It’s difficult to tell because many medieval drawings of trees are rather twig or grain-like.

Assuming this is a bird in a nest, it’s almost impossible to guess what kind of bird it is—it’s not very clearly drawn and many birds nest on the ground or in high places. There is another bird, or possibly another rendition of the same bird, in the upper right corner, which may or may not relate directly to the one below.

Summary

I’m sure there are already many explanations for the identity and meaning of the VMS bird—there are thousands of bird stories, many of them featuring raptors that nest in high places—but I wonder if anyone has suggested that this might be the ancient phoenix, in the style of some of the more ancient Persian harvest birds, or the firebird in the Aberdeen Bestiary presiding in its aromatic container. Could the grain-like “tree” that hovers over the VMS bird represent both crop fertility and the tree of life? These days, we’re accustomed to very extravagant drawings of phoenixes, but the earliest depictions of the symurgh and its medieval European variations were much simpler than they are now.

A phoenix drawn with Asian influence snatches baby Zal, the legendary warrior king and father of Rostam, in a detail from a c. 1370 manuscript from the Topkapi Palace Museum.

It was not uncommon for the simurgh to be drawn next to steep hills. The example on the right shows the phoenix rescuing baby Zal by a tall tree-flecked tor. The “Conference/Councourse of Birds” (a legend about birds seeking the phoenix to be their king) also frequently shows the birds against the backdrop of a steep mountain.

I’m not inclined to identify the VMS bird as a phoenix—the surrounding images don’t seem to confirm that idea. The bird in the top-right corner looks like it’s flying past a cloud deluge rather than into the sun to be consumed by flames, and phoenix myths don’t shed any light on the mysterious half-hidden figures on the left. But I wanted to mention the possibility in case there might be other myths or associations with the phoenix that could explain aspects of this folio. Three of the corners look like there is something flowing out of them, so the bottom-right is unique in having a plant-like structure rather than streams of mist or water (or spiritual energy). I’ve been assuming each corner is somehow associated with the others, but how direct that association might be is hard to say.

So, it’s just a thought (out of many), something to mull over until more is known about the bird.

J.K. Petersen © Copyright 2017 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved