The Plant with the Mysterious Root

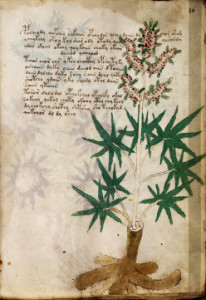

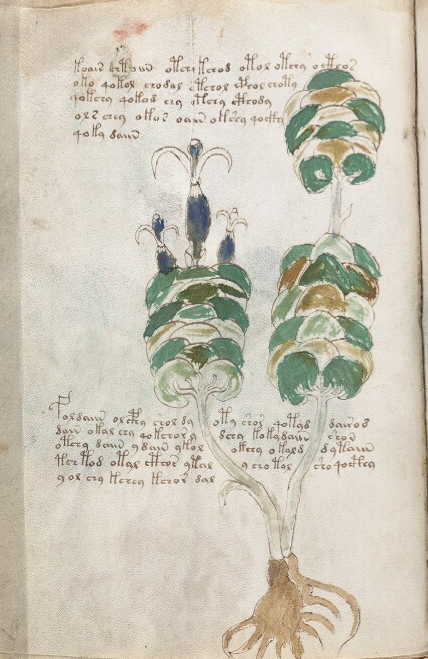

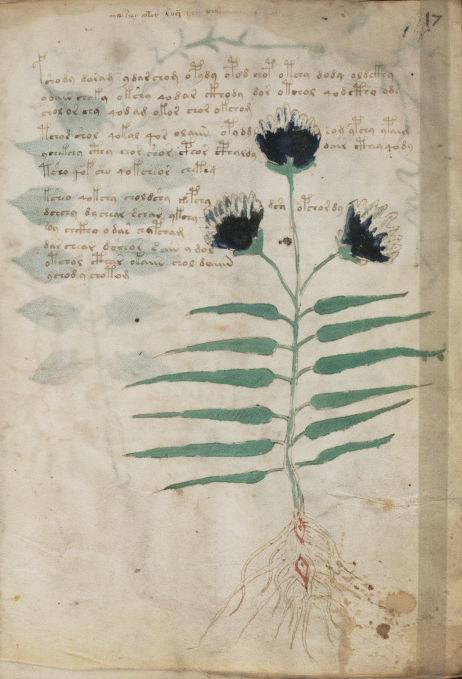

Plant 17r is a slender plant with a stem that branches at the top. Three puffs of blossoms are painted dark blue toward the calyx, but left unpainted across the top. This might suggest a two-toned blossom, or possibly sunlight on the top of a blossom, or two stages of development (like a dandelion changing from petals to fuzzy seed forms), or might simply be an effort to draw the flower to look three-dimensional.

Plant 17r is a slender plant with a stem that branches at the top. Three puffs of blossoms are painted dark blue toward the calyx, but left unpainted across the top. This might suggest a two-toned blossom, or possibly sunlight on the top of a blossom, or two stages of development (like a dandelion changing from petals to fuzzy seed forms), or might simply be an effort to draw the flower to look three-dimensional.

The leaves are opposite, lanceolate, and very slender. Note that they stand out from the central stem, and not from branching stems. Also noteworthy is how straight and stiffly they are positioned—many plants have a slight curve or droop to the leaves and quite a few VMS plants are drawn with a significant droop. The veins are not indicated, so it might be a plant with parallel veins (which do not show up well when the leaves are narrow), or very small hard-to-see veins.

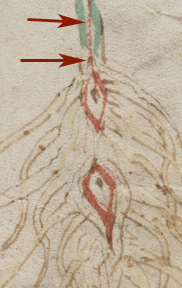

The roots are long and stringy, radiating from a larger central mass that includes two eye-like forms rimmed in red. This is the most curious part of the drawing as the unusual shapes look like they might have symbolic significance. Note that there is a red line extending from the top “eye” into the stem that does not continue down to the lower eye.

The roots are long and stringy, radiating from a larger central mass that includes two eye-like forms rimmed in red. This is the most curious part of the drawing as the unusual shapes look like they might have symbolic significance. Note that there is a red line extending from the top “eye” into the stem that does not continue down to the lower eye.

Other Curiosities

This folio is also unusual in that it includes a fairly long line of marginalia along the top, in a hand that resembles the handwriting on the last folio. Unfortunately most of the text to the right is faded and almost impossible to see. This folio also has some unusual characters next to the plant, including a diminutive version of one of the VMS glyphs which is usually drawn like a capital letter. The marginalia is a subject on its own, and will be discussed in a separate blog.

Prior Identifications

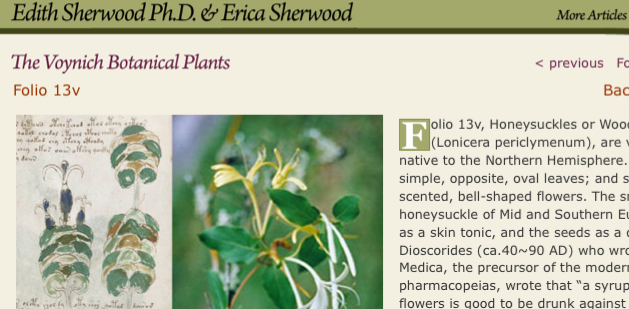

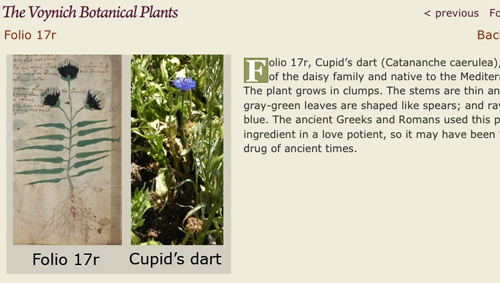

Edith Sherwood has identified Plant 17r as Catananche caerulea. I disagree with quite a few of Sherwood’s plant IDs, but this one seems reasonable for a number of reasons: the VMS flowers have been painted blue and appear as “puffs” at the end of slender stems, and the leaves are narrow. The common name of “Cupid’s Dart” from an ancient Greek and Roman practice of using the plant in love potions might also fit the shapes in the VMS root.

Edith Sherwood has identified Plant 17r as Catananche caerulea. I disagree with quite a few of Sherwood’s plant IDs, but this one seems reasonable for a number of reasons: the VMS flowers have been painted blue and appear as “puffs” at the end of slender stems, and the leaves are narrow. The common name of “Cupid’s Dart” from an ancient Greek and Roman practice of using the plant in love potions might also fit the shapes in the VMS root.

Sherwood didn’t comment on the imagery in the roots. The long, stringy unpainted tendrils include two eye-like almond-shaped forms with a dark dot inside and a lining of red around the rim. Red pigment has been used sparingly in the plant images, so the use of red in such a specific way might be significant. It’s not uncommon to find roots with holes or hollows or with red in the roots, but this specific shape and the double nature of the “eyes” is unusual.

What are Those Eye Shapes?

The resemblance to the opening of a vagina would be difficult to dispute, and would fit if the plant is an ingredient in love potions, although it doesn’t entirely explain why there are two red shapes. Could this be a reference to lesbian love? Male homosexual imagery was very common in classical Geek pottery, but not very common in medieval times. Images of lesbian love are rare in all historic time periods. The female erotic painting on the right, from the walls of Pompeii, is one of the few that has come down to us from ancient times.

The resemblance to the opening of a vagina would be difficult to dispute, and would fit if the plant is an ingredient in love potions, although it doesn’t entirely explain why there are two red shapes. Could this be a reference to lesbian love? Male homosexual imagery was very common in classical Geek pottery, but not very common in medieval times. Images of lesbian love are rare in all historic time periods. The female erotic painting on the right, from the walls of Pompeii, is one of the few that has come down to us from ancient times.

Perhaps the VMS “eyes” are not two vaginas. Maybe one eye-shape is intended as a vagina and the other as an anus (I know, it’s not a very polite term, but if that’s what it is, we might as well say it). It’s even possible those long stringy roots are intended to double as pubic hair.

When you have a document that is carefully crafted, extensive, and yet unreadable, it’s possible that forbidden subjects are hidden in the text and possibly also encoded into the drawings. The manuscript has an unusual preponderance of female nymphs (only a few appear to be male) which might be another reference to lesbianism, but not much has been said about this subject, and the manuscript as a whole seems more clinical than erotic, and doesn’t appear to confirm this idea. Still, the possibility should remain open until more is known.

Getting back to the plant ID…

Other Possible IDs

Even though Catananche caerulea might be a reasonable ID, given the shape of the plant and its relation to love potions, I didn’t want to assume it was the only one possible. The VMS flowers look quite thick and dense, in contrast to the light airy petals of C. caerulea and C. caerulea has alternate, somewhat clasping, droopy leaves, while the VMS leaves are opposite, straight, and distinctively horizontal, so I searched for a closer match.

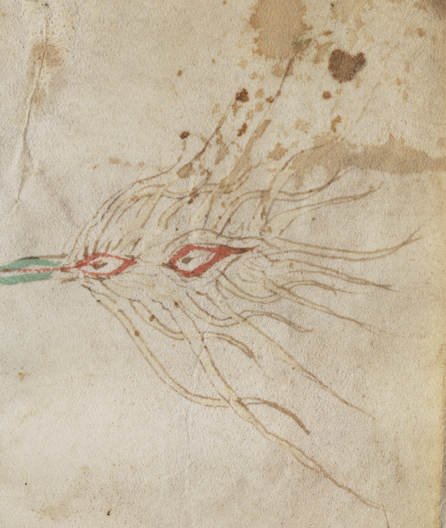

It occurred to me, when looking at the root, that if the two red shapes are eyeballs, then turning the root sideways is reminiscent of certain forms of sea-life, a resemblance that occurs in a few other VMS plants, such as the root that looks like an octopus and another that looks like a jellyfish.

It occurred to me, when looking at the root, that if the two red shapes are eyeballs, then turning the root sideways is reminiscent of certain forms of sea-life, a resemblance that occurs in a few other VMS plants, such as the root that looks like an octopus and another that looks like a jellyfish.

If one turns the root upside-down, it has a rather torch-like appearance, like two candle flames radiating waves of heat. There are quite a few plants that are dipped in wax and lit to create torches, such as Aaron’s rod (Verbascum), but it’s usually the stem and flowers, rather than the roots, that are used.

Plant 17r is a rather fun image incorporating shapes that could be interpreted in many different ways.

Searching for a Better Match

There are many plants with leaves like 17r, but most of them don’t have puffy flowers—many have flower spikes, bell-shaped blossoms, or a small number of petals. The challenge is to find a plant that matches all characteristics of the drawing. Some of the Dianthus plants with multiple petals are similar, but they tend to have clasping leaves, unlike Plant 17r.

Phylica capitata has slender, opposite leaves, but they are not as long as 17r.

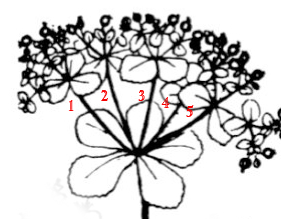

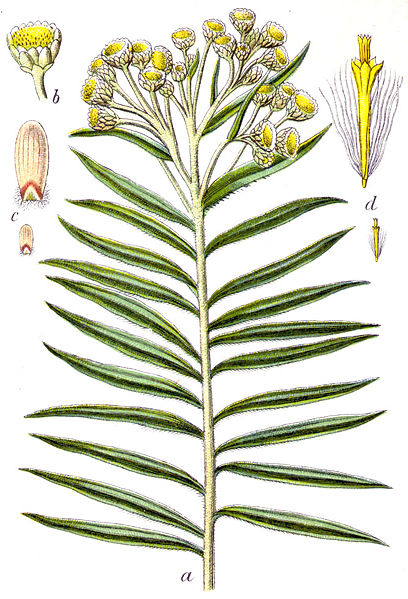

There is a plant that has very stiff, somewhat horizontal leaves, in the aster family, called Anaphalis (see left)—known to many people as “pearly everlasting”. The blossoms have a papery texture and, when dried, retain their original color, making them a favorite in dried flower arrangements. The roots often have a slightly knobby portion with many long stringy root hairs, similar to the VMS root. The flowers are quite dense, like those of the VMS plant, but they are not typically blue. Most are white or pink with yellow centers and the plant is not native to Europe—it is from India, parts of east Asia, and North America.

There is a plant that has very stiff, somewhat horizontal leaves, in the aster family, called Anaphalis (see left)—known to many people as “pearly everlasting”. The blossoms have a papery texture and, when dried, retain their original color, making them a favorite in dried flower arrangements. The roots often have a slightly knobby portion with many long stringy root hairs, similar to the VMS root. The flowers are quite dense, like those of the VMS plant, but they are not typically blue. Most are white or pink with yellow centers and the plant is not native to Europe—it is from India, parts of east Asia, and North America.

One of the problems with identifying the VMS plant is deciding whether the opposite leaves are literal. If they are, then 17r is neither Catananche or Anaphalis which both have alternate leaves. I’ve spent a significant amount of time evaluating all the plants to try to determine which aspects are symbolic, which are referential (not necessarily literal), and which are literal. I have the impression that leaf margins, veins, and possibly the leaf arrangements are meant to be naturalistic in many of the plants. The roots sometimes have fanciful embellishments, but perhaps they are meant to be mnemonic, as in many traditional herbals. If the 17r leaves are meant to be literal, then perhaps there are other plants that should be considered.

Further Possibilities

Valerian has long narrow leaves and a slightly bulbous root with long stringy root hairs, but the leaves do not branch off the main stem, they are odd-pinnate and there is another VMS plant that more closely resembles Valeriana than 17r.

Scabiosa suceisa has roots and flowers that resemble Plant 17r. The roots come from a thicker middle portion and branch out into long white, stringy tendrils. The flowers are dense with a slightly protruding calyx, and they are often a deep violet color, but the leaves are wider than Plant 17r and come up mostly from the base of the plant—they do not distribute themselves evenly along the stem. But…

…there is another “Scabiosa” that might qualify. Scabiosa syriaca (Cephalaria syriaca—right), commonly called Makhobeli, has puffy flowers and long slender opposite leaves. It originated in Syria and has spread across Eurasia. The seeds are used as a flavoring for bread but it was not traditionally used as medicine and no particular significance has been given to the roots, nor could I find any records of a relationship to eyes or to female concerns. Morphologically it matches well to Plant 17r, but it doesn’t seem related in other ways.

…there is another “Scabiosa” that might qualify. Scabiosa syriaca (Cephalaria syriaca—right), commonly called Makhobeli, has puffy flowers and long slender opposite leaves. It originated in Syria and has spread across Eurasia. The seeds are used as a flavoring for bread but it was not traditionally used as medicine and no particular significance has been given to the roots, nor could I find any records of a relationship to eyes or to female concerns. Morphologically it matches well to Plant 17r, but it doesn’t seem related in other ways.

There is a SW African plant called Mesembryanthemum viridiflorum that has puffs of flowers, very stiff opposite leaves growing from long stems, and a knobby root, but the calyx is very long and almost wraps around the flowers, and the leaves don’t have petioles and are not as long as the leaves of 17r. It is not as upright as the VMS plant either. I thought it was worth mentioning due to the shape of the flowers and the opposite leaves, but I don’t think it’s a close match to the VMS.

Getting Closer

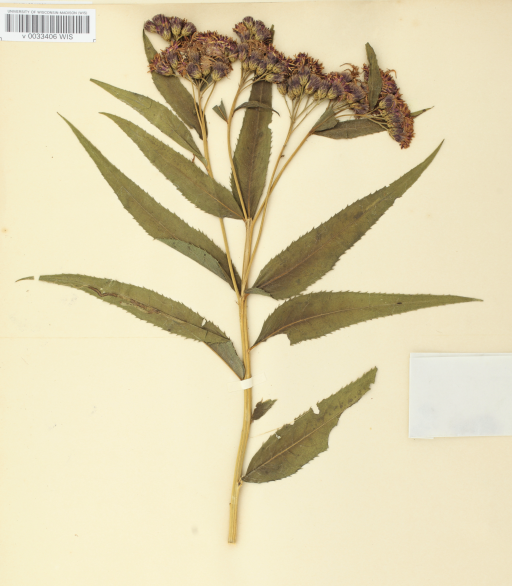

Vernonia fasiculata courtesy of Wisconsin Flora.

Vernonia crinita, Vernonia fasciculata, and Vernonia noveboracensis have more in common with Plant 17r than most plants, including those already mentioned. They are erect, with long, narrow, opposite leaves (or a mixture of alternate and opposite), and branching puffy purple flower heads that become darker and stiffer when they turn to seed. The roots of V. fasiculata look very much like the VMS roots, a thick mat of long stringy whitish tendrils.

There is also a Hawaiian species of Vernonia with opposite leaves, but the leaves are stubbier than most of the North American species.

Summary

So there is a plant that closely resembles the VMS plant on all counts: thick puffy branching flowers, long thin opposite leaves distributed evenly up the stem, and a long stringy whitish root. Sometimes the stem is red.

The oil from Vernonia is commercially used as a binder and the roots of certain North American species are used as a tonic for certain female conditions, which might explain the imagery in the VMS roots.

Unfortunately, varieties of Vernonia that most closely resemble the VMS plant are not native to Europe. If Plant 17r is Vernonia, the VMS illustrator would have to know New World plants to include it, and other aspects of the manuscript lean toward a pre-Columbus timeline. Even so, I prefer not to assume an exact date for the creation of the VMS, It simply feels to me, on a detail-by-detail basis, to be an earlier date, possibly late 14th century or thereabouts.

Because Vernonia matches so well compared to other options, I searched for Vernonia species with origins in the Old World and discovered that Vernonia galamensis is native to east Africa. This seemed promising until I noticed that V. galamensis has alternate leaves (which is also true of some of the New World Vernonias). It is less like the VMS drawing than the New World varieties mentioned above.

So, unless one is willing to accept that the VMS illustrator knew about New World plants, there are no perfect Old World matches, but the latter ones above are fairly close. As for the interpretation of the shapes in the root, there are many possibilities, some of which were socially taboo in the Middle Ages.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2013 All Rights Reserved