Category Archives: The Voynich Large Plants

Large Plants – Folio 11r

Large Plants – Folio 10v

Large Plants – Folio 10r

Voynich Large Plants – Folio 9v

There is significant controversy (and consternation) over the identities of most of the Voynich plants. The illustrator was reasonably good on details, but short on artistic skills. That’s not to say the drawings are bad—they are better than many of the herbal-style drawings of the time—but they don’t yield their secrets easily, even after centuries of study.

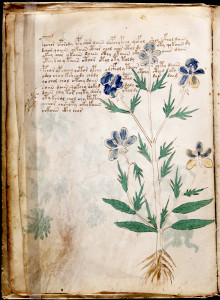

One plant that has escaped most of the controversy is the flower on Folio 9v. I haven’t searched the Web extensively for plant IDs for this page, but the few that I’ve seen all state that this is probably Viola tricolor. I readily agree that it looks like a viola and V. tricolor, a common wildflower, should certainly be considered, but I don’t think we can assume it’s V. tricolor without considering other possibilities.

Alternative IDs

There is a field pansy called Viola arvensis that matches Plant 9v quite well. It is broadly distributed in Europe and North America and has leaves similar to Plant 9v. Many violas have rounded or heart-shaped leaves that don’t match the VM drawing at all, but V. arvensis has a mix of lanceolate and spidery palmate leaves very much like Plant 9v. V. arvensis is often white and yellow or light blue and yellow, but some variations lean toward violet-blue with yellow. Like Plant 9v, V. arvensis branches lightly and has leaves alternating up the stem at some distance—an important detail since many violas have basal whorls and tend not to branch.

There is a field pansy called Viola arvensis that matches Plant 9v quite well. It is broadly distributed in Europe and North America and has leaves similar to Plant 9v. Many violas have rounded or heart-shaped leaves that don’t match the VM drawing at all, but V. arvensis has a mix of lanceolate and spidery palmate leaves very much like Plant 9v. V. arvensis is often white and yellow or light blue and yellow, but some variations lean toward violet-blue with yellow. Like Plant 9v, V. arvensis branches lightly and has leaves alternating up the stem at some distance—an important detail since many violas have basal whorls and tend not to branch.

Despite its promising characteristics, Plant 9v probably isn’t V. arvensis. In real life it tends to be a bit squatter than this botanical drawing, which is stretched out to show details, and it is more often white than blue. But the key difference is the shape of the flowers. The shape and proportion of the petals varies from one species of viola to the next and V. arvensis flowers have a double pair at the top and a broader tongue-shaped petal at the bottom. Plant 9v, in contrast, has three at the top, rather than four.

The Corsican violet (V. corsica) and Viola dubyana both have many characteristics in common with V. arvensis and their colors range from violet-blue to a light purple. Due to the color, both these species match 9v a little more closely than V. arvensis but, once again, the shape of the flowers is wrong.

Odd Anomalies

But wait a moment.. there’s a mystery in the making. Viola tricolor doesn’t match either, even through the leaf shapes, the spacing of the leaves, the roots, and the color are a good match. As with the previous flowers, there are two pairs of petals above and a broader one below. Even an extensive search of other viola species fails to turn up an example that matches all the characteristics of the VM plant—the leaf shapes, growth habit and flower shape/colors.

Sorting out the anomaly. Could it be that the flowers on Plant 9v were drawn upside-down? If they are reversed, they would be a good match for any of the above species. This little detail, which I haven’t seen mentioned anywhere else on the Web, surprised me until I thought about it for a few moments. I’d love to believe there is some mystery message in the orientation of the flowers but…

Before offering an explanation for this anatomical curiosity, it’s worth noting that there is text hidden behind the blue ink in one of the blossoms. I did some Photoshop adjustments to see if the obscured text could be seen more readily and I think I can make out the letter p on the two lower petals (at least) and what appears to be “por” on the upper one. I’ve noticed annotations on other plants, the letter “g” on a leaf that was painted green and the letters “r o t” (German for red) on the unpainted stem of plant 4r. If this says “por” then it may mean purple (or violet) as por is an abbreviation for purple in several languages.

Before offering an explanation for this anatomical curiosity, it’s worth noting that there is text hidden behind the blue ink in one of the blossoms. I did some Photoshop adjustments to see if the obscured text could be seen more readily and I think I can make out the letter p on the two lower petals (at least) and what appears to be “por” on the upper one. I’ve noticed annotations on other plants, the letter “g” on a leaf that was painted green and the letters “r o t” (German for red) on the unpainted stem of plant 4r. If this says “por” then it may mean purple (or violet) as por is an abbreviation for purple in several languages.

Many varieties of Viola tricolor, and the Corsican viola, are distinctly purple and the fact that the VM plant is painted blue (the trace of purple in the above example is a Photoshop artifact from trying to make the text more clear) might be due to the painter’s limited palette. Since 15th century pigments were mixed from a variety of natural materials, it took some skill to blend them. Even if the color combination was correct (e.g., red and blue to make purple), the chemical balance might not work and the result could be a muddy mess. The person blending the colors also had to have a sense of which colors to mix.

Many varieties of Viola tricolor, and the Corsican viola, are distinctly purple and the fact that the VM plant is painted blue (the trace of purple in the above example is a Photoshop artifact from trying to make the text more clear) might be due to the painter’s limited palette. Since 15th century pigments were mixed from a variety of natural materials, it took some skill to blend them. Even if the color combination was correct (e.g., red and blue to make purple), the chemical balance might not work and the result could be a muddy mess. The person blending the colors also had to have a sense of which colors to mix.

So, it’s possible that the annotation means purple, but purple pigment was not available (or too much work to create), or that por stands for something else.

A Mystery or a Practical Explanation

But getting back to the strange upside-down flowers… soon after I discovered the Voynich manuscript, I noticed some of the more identifiable plants may have been painted from herbarium samples. They have a flattened aspect that is not characteristic of plants drawn from life. This is particularly noticeable in the leaves. If Plant 9v had been gathered and flattened and the viola flowers flipped up to prevent the hooked part of the stem from breaking when pressed in the natural direction, that might account for the odd reversal. The person who painted them may not have cared if the upper or lower part of the flower was painted yellow or may not have noticed the petal reversal in the underlying drawing. As has been mentioned a few times, the person who painted the plants is not necessarily the same as the person who drew them.

But getting back to the strange upside-down flowers… soon after I discovered the Voynich manuscript, I noticed some of the more identifiable plants may have been painted from herbarium samples. They have a flattened aspect that is not characteristic of plants drawn from life. This is particularly noticeable in the leaves. If Plant 9v had been gathered and flattened and the viola flowers flipped up to prevent the hooked part of the stem from breaking when pressed in the natural direction, that might account for the odd reversal. The person who painted them may not have cared if the upper or lower part of the flower was painted yellow or may not have noticed the petal reversal in the underlying drawing. As has been mentioned a few times, the person who painted the plants is not necessarily the same as the person who drew them.

So, there may not be any mystery hidden in the reverse orientation, but it’s a tantalizing clue to the creation of the manuscript if the VM plants (or some of them) are drawn from gathered specimens. It means someone took the time to press them and to do so in a way that reveals the fronts of some flowers and the backs of others, a good practice when creating botanical drawings so that the shape and size of the sepals can also be seen.

Posted by J.K. Petersen

Voynich Large Plants – Folio 9r

The Plant with the Whirligig Leaves

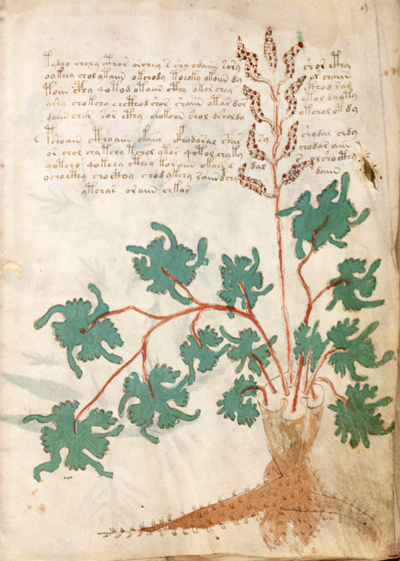

Plant 9r fills most of the page from top to bottom and features a distinctive seed stalk with a long straight, reddish stem, wiggly seed pods extending to both sides, with red seeds as they might look inside their pods.

Plant 9r fills most of the page from top to bottom and features a distinctive seed stalk with a long straight, reddish stem, wiggly seed pods extending to both sides, with red seeds as they might look inside their pods.

The leaf stems are also red, each one featuring a distinctive “rotating” bird-like leaf that must have been quite challenging to draw. I’m fascinated by these leaves, which are more intricate than most of the VMS plants. Each has four long protruding beak-like bumps with graceful curves and rounded ends. Between them are ruffled edges reminiscent of feathers or something else with a bumpy texture.

The root is quite thick and painted brown, with carefully distributed double tufts of hairs and a large flat bole that was left unpainted.

In botanical illustration, boles are usually shown for plants that are grown from root stocks (like roses), or which can be generated from tubers (like potatoes), or which are cut down regularly to encourage new growth, as with quite a few plants that die into the roots in winter and re-emerge in spring. They also sometimes represent aquatic plants (with the “bole” being the surface of the water). I don’t know what it means on the VMS plant, but I suspect that this might be a plant with a very thick or fibrous root with stalks that die back or are cut back in the winter.

Prior Identifications

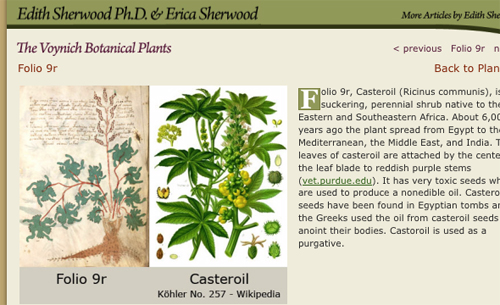

Edith Sherwood has identified this plant as Ricinus communis (castor oil plant), but I strongly disagree with this ID. Ricinus has large round greenish-blue seed pods that are similar to spiny chestnut pods. It does not have pea-like seeds extending outwards in long slender pods. Also, ricinus has very distinctive star-like leaves that really don’t look like those of Plant 9r, even if you stylize them.

Edith Sherwood has identified this plant as Ricinus communis (castor oil plant), but I strongly disagree with this ID. Ricinus has large round greenish-blue seed pods that are similar to spiny chestnut pods. It does not have pea-like seeds extending outwards in long slender pods. Also, ricinus has very distinctive star-like leaves that really don’t look like those of Plant 9r, even if you stylize them.

What convinces me even more that Plant 9r is not Ricinus is that there is quite an accurate drawing of Ricinus on VMS folio 6v. Plant 6v could be either Ricinus or chesnut, but the way the seeds are drawn (at the end of a long stock rather than at the ends of multiple branches) is a bit more similar to Ricinus than the various chestnut species. Either way, it is evident that the VMS illustrator could draw Ricinus or chestnut-like pods quite well and Plant 6r does not look like Ricinus.

Usually I have multiple IDs for any specific VMS plant. Even if you know the plant (e.g., viola), each plant can have several varieties, and it’s hard to pin down an exact species from an amateur drawing. Plant 9r is different. I do have a few alternatives, but only two really grab me and match well to the characteristics of the plant. One is from Eurasia, the other from east Asia. But first, a third alternative that matches less well but does include a reference to birds…

Alternate IDs

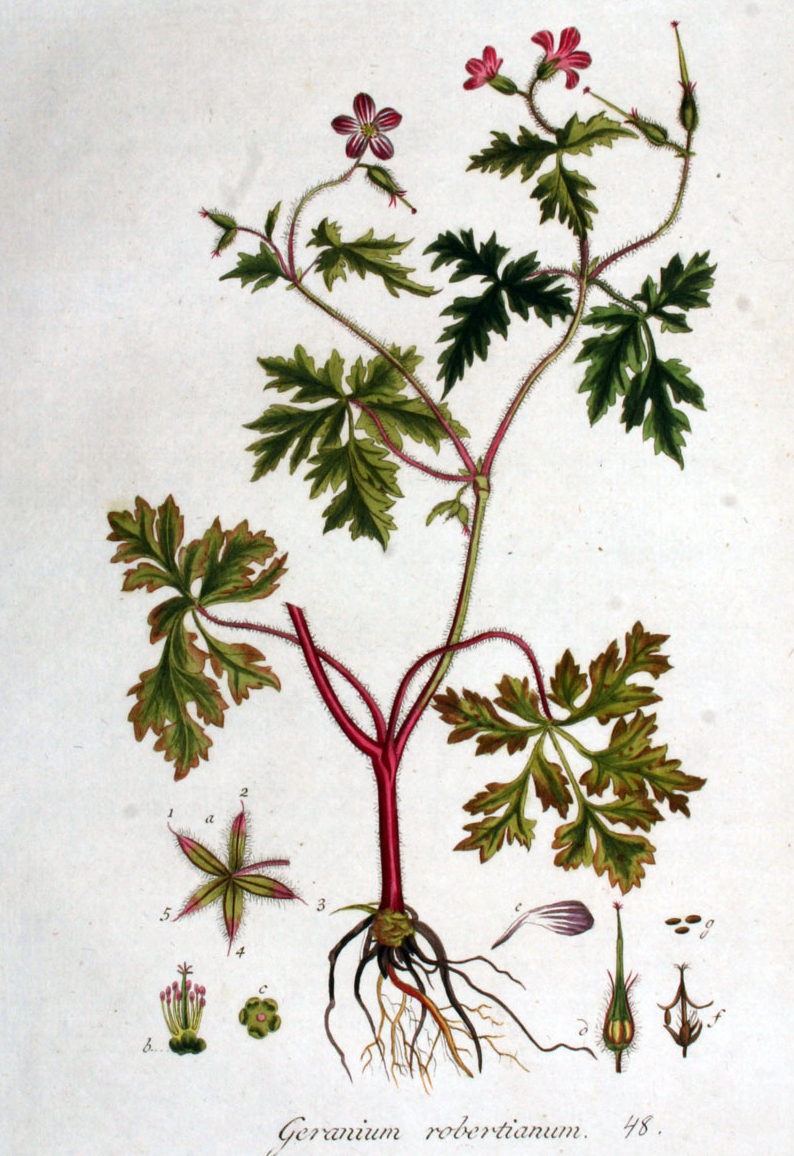

Stinking crane’s bill (Geranium robertianum) is a widespread Eurasian plant with red stems, very intricate leaves, red seeds, and roots that are a little thicker than the stem. It’s not a perfect match to Plant 9r, however. The seeds are individual, with long beaks that look like the heads of cranes. The VMS plant has branching pods with many seeds in each pod—quite a different arrangement.

Stinking crane’s bill (Geranium robertianum) is a widespread Eurasian plant with red stems, very intricate leaves, red seeds, and roots that are a little thicker than the stem. It’s not a perfect match to Plant 9r, however. The seeds are individual, with long beaks that look like the heads of cranes. The VMS plant has branching pods with many seeds in each pod—quite a different arrangement.

It’s tempting to think the bird-like leaves might be a mnemonic for the common name “crane’s bill” or “dove’s foot”, the leaves do have a rather bird-like appearance (they remind me of flying egrets), but it’s hard to believe that the VMS illustrator would display pea-like pods for a plant with beak-like seeds. Also, crane’s bill (known as Herb Robert in the culinary world) is a small delicate plant and does not have a thick base or a prominent bole.

Two Plants with Better Possibilities

There are two plants that look very much like Plant 9r. I’ll describe the east Asian plant first…

Plume Poppy [Courtesy of Jari Särrkä]

Plume poppy stems are not red but the toxic sap that oozes out when the stem is broken is orange.

The plume poppy does not have pods, so one would have to argue that the VMS seeds represent branching plumes rather than pods, but I’m leaning toward pods, which means there is another plant more similar to Plant 9r than plume poppy…

The plant that seems to hit the most marks is Russian kale.

Russian kale is a popular culinary plant in the mustard family, which is highly variable in shape and size. Russian kale is usually harvested when the leaves are young and the plant is small and bushy, but it can grow quite tall and tree-like, with thick stems. The stalks range from bright red to reddish-purple, and the leaves have very intricate, lacy and sometimes deeply incurled leaves. It is a north-temperate Eurasian plant and thus more likely to be in the VMS than a plant from eastern Asia like the plume poppy.

What is particularly interesting about Russian kale, besides the very complex leaf margins, is the seed pods. It has long pea-like pods with seeds that create lines of bumps within the pods, and they are arranged on a long stalk very much like the pods on Plant 9r. They even have a gentle S-curve shape that matches the VMS pods. The only part that doesn’t match is the color. Kale seeds range from a charcoal-brown to black, not the red color of the VMS plant.

What is particularly interesting about Russian kale, besides the very complex leaf margins, is the seed pods. It has long pea-like pods with seeds that create lines of bumps within the pods, and they are arranged on a long stalk very much like the pods on Plant 9r. They even have a gentle S-curve shape that matches the VMS pods. The only part that doesn’t match is the color. Kale seeds range from a charcoal-brown to black, not the red color of the VMS plant.

Most varieties of kale have leaves that grow from a central rosette, but there are a few that branch like the VMS plant, and there are others called “tree kale” that are shaped like mini palm trees (check out Google Image Search for “tree kale” to see some interesting variations). Tree kale might explain the large bole.

It’s not a perfect ID, however. Kale is a biennial. It’s not a perennial like rhubarb that dies back and grows up again from the same stalk each year. I’m tempted to include rhubarb (right) as a possible ID for 9r, but it has the same problems as plume poppy (the seeds are not in pods) and there’s another VMS plant that resembles rhubarb more closely than this one.

The Plant 9r Rorschach Test

I cannot make sense of the leaves.

I cannot make sense of the leaves.

The lacy edges of kale leaves do somewhat resemble the VMS leaves, especially if you try to flatten them as herbarium specimens but, if Plant 9r is kale, why did the illustrator draw them in such a decorative and regimented way? I also find it hard to get the idea of birds out of my head because they remind me so much of egrets, but they may be something other than birds, like long-tailed sheep or running lions rampant. Note how the leaf on the bottom right looks like natural kale while those on the left almost have legs and heads with wings or garments.

Summary

I tried to find some alternate names that might explain the apparent symbolism in the leaves. In French, kale is known as chou frisé, in German it’s Grünkohl (essentially the same as in Scandinavian languages). Other languages have variations on kel or col—all of which refer to cabbage in rather pedestrian terms. In Greek, it’s λάχανο, in Russian, it’s капуста with various modifiers. In some languages it’s referred to as the plant that is torn (probably a reference to the leaf shapes).

None of these seem to shed any light on the decorative leaves or help to confirm if the plant is kale.

So I’m a bit stumped. I think it’s a reasonably good match for Russian kale, but I don’t fully understand the significance of the leaves. I’ll leave it to your imaginations and if a better idea crosses my mind, I’ll upload it as a postscript.

J.K Petersen

Copyright 2013 J.K. Petersen All Rights Reserved

Originally posted July 2013. Returned to draft mode a couple of weeks later (I was hoping to figure out the meaning of the leaves). Reposted August 2017 without changes to the original post except to crop the pictures (yes, you guessed right, I still haven’t figured out the leaves but I haven’t stopped trying).

Large Plants – Folio 8v

Voynich Large Plants – Folio 8r

Note: This is a re-upload of a blog I posted in July 2013 and removed soon after, along with a number of other large-plant articles, because I felt I was giving too much away (I thought I was close to finding a solution to the VMS—a common affliction among VMS researchers 🙂 ). I have trimmed the images slightly, added a hyphen, and fixed a comma. Other than that, I have not altered the text in any way because my opinion about the identity of the plant hasn’t changed at all in the intervening time.

Plant 8r

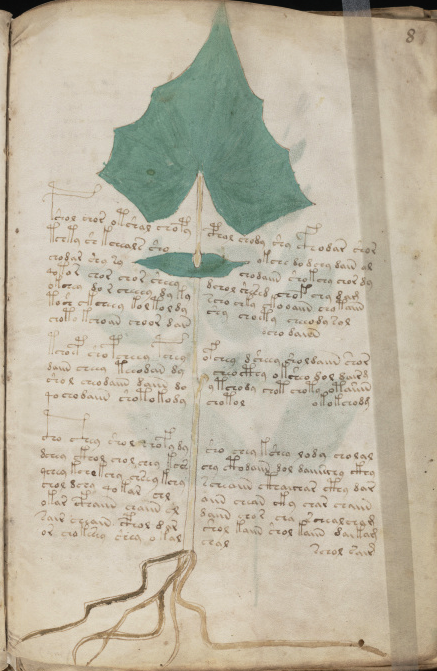

Plant 8r stands boldly upright, filling the middle of the page from top to bottom, with text flowing around it on either side. There is more text than on many big-plant pages, three moderately long paragraphs.

Plant 8r stands boldly upright, filling the middle of the page from top to bottom, with text flowing around it on either side. There is more text than on many big-plant pages, three moderately long paragraphs.

It has a slender erect stem, very slightly colored with a pale amber wash, a single spade-like leaf drawn erect and painted in quite a flat shade of medium green. There is something that resembles a smaller leaf or node just below it. Just above the node, the stem is slightly more bulbous, a feature that appears to be deliberate, rather than a slip of the pen.

The roots are long and spindly and colored medium-dark to light brown, spanning the width of the page.

There are a number of plants, both New and Old World that have spade-like leaves, some of which are quite erect. What is more difficult to interpret is the node-like green spot under the leaf. This is less common and might aid in identification, but it depends how one interprets it. Is it a leaf (clasping), a leafy node? Or something else?

Prior Identifications

Edith Sherwood has identified this plant as green pea (Pisum sativum). I suppose this is reasonable if one interprets the green spot as a stem that goes through a rounded leaf, is in Pisum and some of the Lonicera species…

Edith Sherwood has identified this plant as green pea (Pisum sativum). I suppose this is reasonable if one interprets the green spot as a stem that goes through a rounded leaf, is in Pisum and some of the Lonicera species…

but, how does one explain the rest of the plant? P. sativum doesn’t have unpierced oversized spade-like leaves, and it’s not an upright plant (it’s a vine that uses tendrils to climb and has a somewhat staircased stem that goes in a different direction after each leaf, as you can see in Sherwood’s picture). Pisum is also distinct for its pods and this feature is absent from the VMS drawing (I’m not saying the VMS illustrator included every feature, but pea plants are almost universally drawn with pods by other medieval artists, or with several leaves in a viny formation and the VMS illustrator did take the time to draw a nub of broken stem and the slightly enlarged part of the stem above the green spot).

Without completely discounting Pisum, there are other plants that resemble Plant 8r more closely than Pisum that should probably be considered as better candidates.

Other Possibilities

One way you might explain the green spot under the leaf is as a reflection. If this is an aquatic plant, then a spot of green is often mirrored on the water just below the leaf, it looks like a little puddle of green. There are many plants that are terrestrial for part of the year and aquatic during seasonal floods. Other plants are primarily aquatic or semi-aquatic. If the green spot is mnemonic, this would be an easy way to remember this as an aquatic plant.

If it is, instead, something more literal, like a leaf or leaf-node, then it narrows down the number of plants that might qualify.

Pericaulis is an attractive plant with masses of blooms. Some species are fairly erect, while others have a more staircased look to the stems. But the “staircasing” is longer than that of Pisum and thus more similar to the VMS drawing. The leaves are not upright, but are shaped similarly to Plant 8r, a characteristic that is more noticeable in the spring before the buds and blooms start to appear.

Pericaulis is an attractive plant with masses of blooms. Some species are fairly erect, while others have a more staircased look to the stems. But the “staircasing” is longer than that of Pisum and thus more similar to the VMS drawing. The leaves are not upright, but are shaped similarly to Plant 8r, a characteristic that is more noticeable in the spring before the buds and blooms start to appear.

What is particularly interesting about Pericaulis is the way the leaves of some species attach to the stem. There is a large broad leaf, a narrow section, and then a rounded clasping part, as can be seen in the image to the right. This characteristic can be found on species growing in Madeira and the Canary Islands, islands off the coasts of Portugal and Spain.

I don’t think Pericaulis is the best candidate for the VMS plant, but I do think it might provide an explanation for the green splot that is under the leaf on the VMS plant. Perhaps VMS 8r is one of the plants that has a double-leaf shape in which the part between the two broader parts looks like a stem.

Colt’s Foot

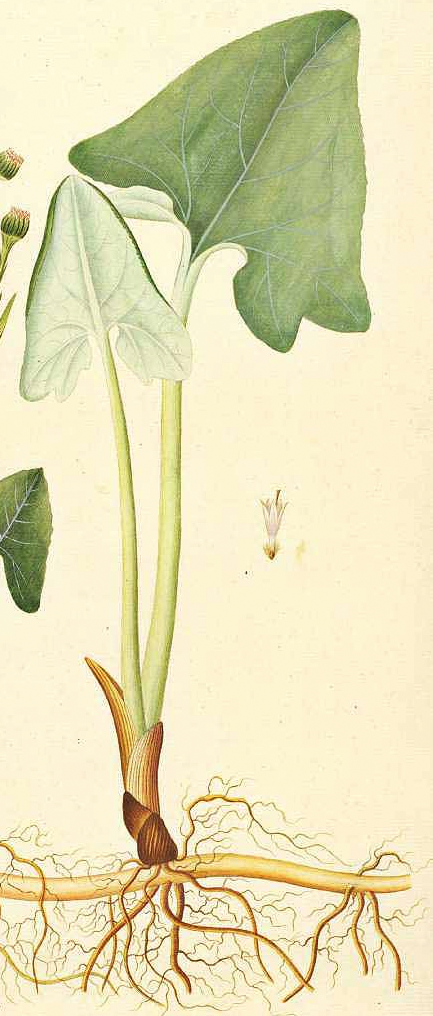

Tusilago farfara, also known as colt’s foot, is a distinctive plant found in many herbal manuscripts. It has leaves shaped similarly to the VMS and they are fairly upright. Where they attach to the stem, they widen into a rounded clasping shape, not quite like the VMS or like Pericaulis, but at least their orientation and shape match Plant 8r reasonably well.

Tusilago farfara, also known as colt’s foot, is a distinctive plant found in many herbal manuscripts. It has leaves shaped similarly to the VMS and they are fairly upright. Where they attach to the stem, they widen into a rounded clasping shape, not quite like the VMS or like Pericaulis, but at least their orientation and shape match Plant 8r reasonably well.

One often sees several leaves before the flower stalks appear and they are distinctive enough to identify the plant without the flowers.

T. farfara has long spindly rhizomes, sometimes drawn in the middle ages to look like a tap root, but more often drawn as long stringy roots with secondary roots. The picture on the left post-dates the VMS, but gives a good sense of the shape of the leaves and their erect posture.

Tussilago spuria has leaves similar to Tusilago farfara and Plant 8r, but the root is quite bulbous and the towering flower stalks set it apart from the more modest T. farfara. Given the difference in the roots, it’s probably not a good candidate for Plant 8r.

Tussilago petasites, now known as Petasites hybridus is somewhere in between T. farfara and T. spuria in terms of similarity to the VMS plant, and it’s a plant that is often submerged in fresh water, but the root tends to be thicker than that of T. farfara.

An interesting characteristic of T. farfara is that if you stand above the plant when the leaves are growing, before the flower stalks are visible, it looks like there is a backwards leaf-cup attached to the stem of the older fully formed leaves. This is because the old leaves fan out and the new leaves poke up in the center right next to them, making it look like the two are attached (very much like the VMS leaf). I don’t know if this might account for the way the VMS plant is drawn and I don’t know if it’s obvious enough to most observers to be relevant, but I thought it worth mentioning.

Indian Plantain

Arnoglossum atriplicifolium (a New World plant) might deserve a brief mention as it sometimes has spade-like leaves and tall slender light-brown stems, but the leaves can be variable, the points are closer together than the VMS leaf, and there are usually many leaves on one stem.

So the above plants have some commonalities with Plant 8r, but are they similar enough? Are there others that should be considered?

Let’s look at the Adenostyles.

Mountain Asters

You may not have heard of them, but Adenostyles are upright plants that are widespread throughout continental Europe and west Asia. They are particularly prevalent in mountainous areas, growing in lush clumps in alpine meadows, often on rocky terrain.

You may not have heard of them, but Adenostyles are upright plants that are widespread throughout continental Europe and west Asia. They are particularly prevalent in mountainous areas, growing in lush clumps in alpine meadows, often on rocky terrain.

The leaves are somewhat variable, from rounded to more sharp or angular, but many of them are spade-like, like Plant 8r, and distinctive enough to recognize before the plants begin to flower.

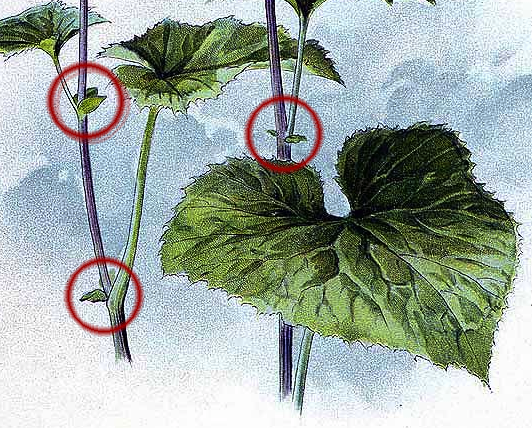

Those of particular interest are species with leaflets at each node where the leaf stalk connects to the stem (upper right), or those with a rounded enlargement at the point where the leaf connects to the stem (left).

Those of particular interest are species with leaflets at each node where the leaf stalk connects to the stem (upper right), or those with a rounded enlargement at the point where the leaf connects to the stem (left).

These kinds of plant structures may account for the green splot under the VMS leaf.

The leaf margins of Adenostyles are serrated (as are all the plants mentioned so far except Pisum and, to some extent, Tussilago farfara), but the serrations vary from one species to the next… some are deeply toothed, while others are so finely indented you almost don’t notice the serrations. I mention this because the VMS leaf is smooth in between the broader points—there’s no obvious indication that Plant 8r has serrated leaves.

Siberian Asters

There is a Siberian plant that somewhat resembles Petasites spurius called Ligularia sibirica. Like P. spurius, it has spade-like leaves and a tall flower spike. It is more delicate and slender, however, more similar to the VMS plant, and the place where the leaf connects to the stem is more rounded and clasping. Like the Adenostyles, it grows in lush clumps in sunny meadows. The leaf margin is not as distinctly angular as Plant 8v, so it might not be the best candidate.

Butterbur

Coming back to Petasites (which is one of the synonyms for Tussilago), there are some species that resemble the VMS plant more closely than those already mentioned.

Petasites radiatus is of particular interest because it grows in wetlands and has tall slender stalks with a single leaf at the top, while older leaves of this species and others sit just below the surface of the water and are seen less distinctly (perhaps inspiring a green splot under the main VMS leaf?).

Petasites radiatus is of particular interest because it grows in wetlands and has tall slender stalks with a single leaf at the top, while older leaves of this species and others sit just below the surface of the water and are seen less distinctly (perhaps inspiring a green splot under the main VMS leaf?).

Often there will be broad patches of skinny stems sticking far up out of the water and no flowers at all. When the flowers do emerge, many are on separate stalks (Petasites spurius also has this characteristic—see illustration right).

The tall stalks are due to the shifting water levels on the edges of rivers or ponds. When the water level goes down, one sees a forest of tall spikes with green tops and the reflections of other leaves under the water. It’s quite an amusing sight.

As with many aquatic, or semi-aquatic plants, P. radiatus has long rhizomes (sideways-growing roots) and long spindly secondary roots, a reasonably good match to the VMS drawing.

I could definitely see an upright spindly plant like Petasites radiatus or P. spurius inspiring a drawing like Plant 8r.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2013 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

Large Plants – Folio 7v

This is a placeholder page.

I have a mass of information on the Voynich Manuscript plants on my hard drive and I am uploading them and linking the pictures as I have time. This is not easy, since I am working long days, these days, but I’ll get the task done as quickly as I am able.