20 October 2017

Relativity may sound like the title for an Einstein blog but it also applies well to medieval musical notation systems, specifically those that differ from the modern western tradition. In the middle ages, there were many forms of relative notation and a particularly interesting one was posted yesterday by René Zandbergen on the Voynich.ninja site.

I’ve had a passion for music all my life and if I could quintuple the length of the day, I would spend one of those extra “lifetimes” as a composer.

I’ve had a passion for music all my life and if I could quintuple the length of the day, I would spend one of those extra “lifetimes” as a composer.

I’m familiar with some of the notation systems in medieval manuscripts, but there are far too many to learn them all, and some of the earlier ones haven’t yet been unraveled, even by the experts. Many of them are comprehensible, however, and old tomes contain a wealth of staffed and unstaffed music (in the sense of not having horizontal lines).

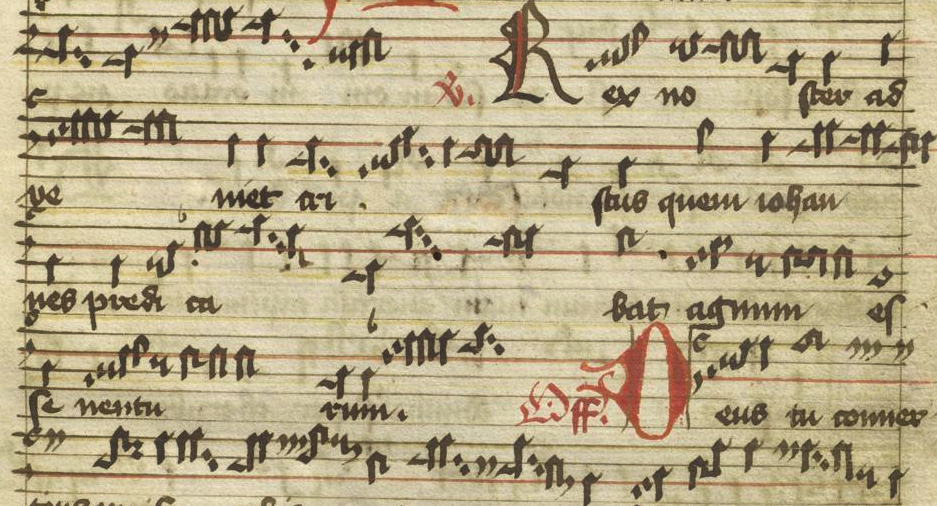

Here is an example of medieval chant music that uses a staff. Note there are only four staff lines and stems are barely visible on the rectangular notes. There are no phrasing arcs as we know them, and no bars to connect the stems but it’s still quite recognizable as western staff-notation:

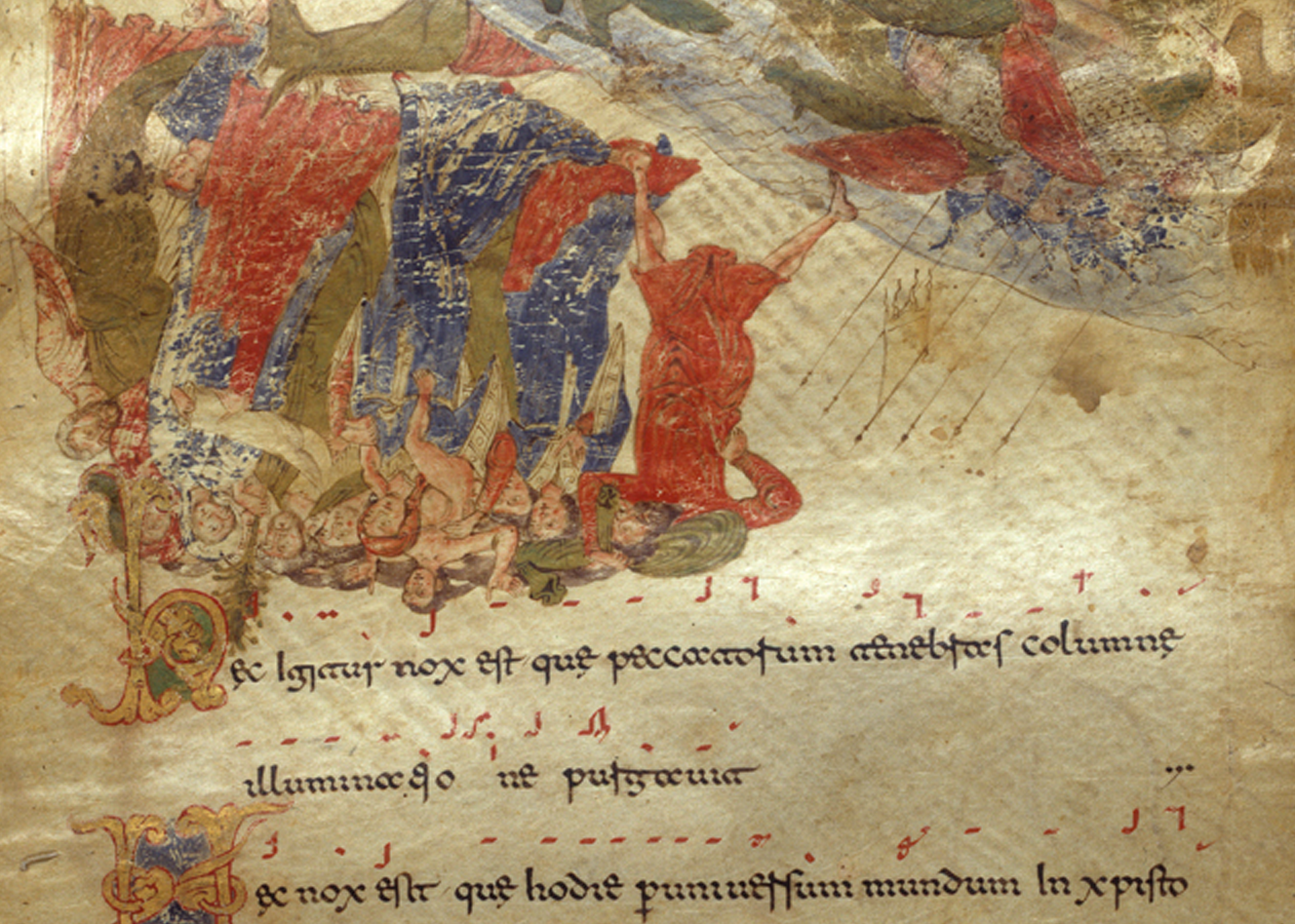

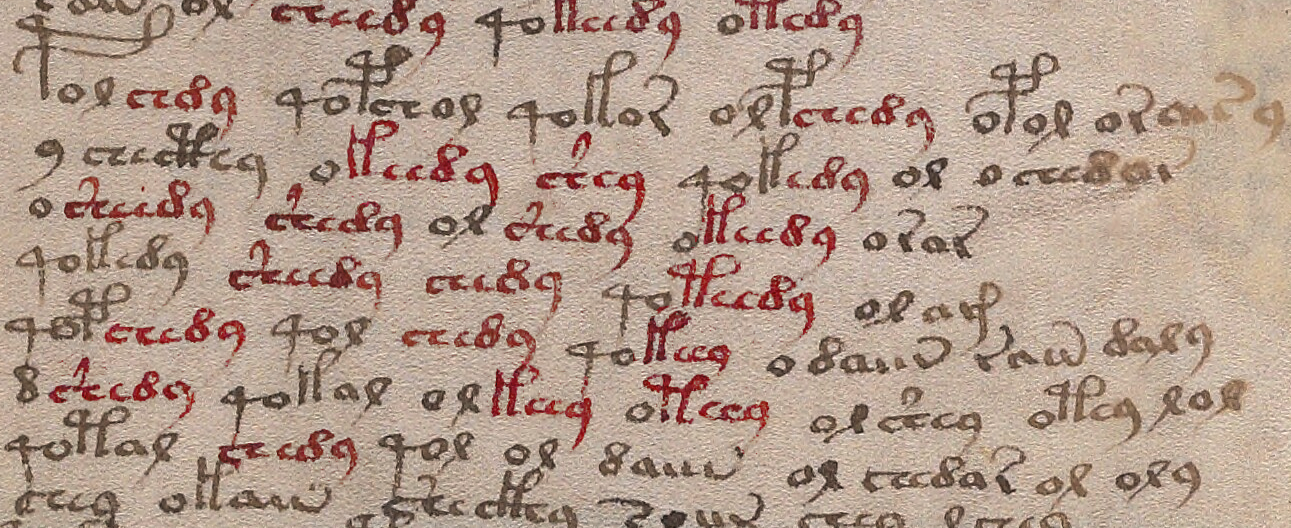

For comparison, this is an unstaffed line of musical symbols in a medieval Italian manuscript (MS 30337). Note how the symbols are laid in a horizontal line with a minimum of vertical positions and do not resemble round-headed notes as we know them:

My interest in music spilled over into my research on the Voynich manuscript almost from the beginning. When you are trying to figure out if something is ciphered, it’s important to search beyond linguistics. Certainly linguistic codes can be hidden in sneaky places, like astronomical charts and musical scores, but there are also non-linguistic ciphers. Take something like the Dorabella code mentioned on Nick Pelling’s cipher blog… the originator was a composer, so if I had time to investigate it, probably the first thing I would look for is a song or some commonality with music.

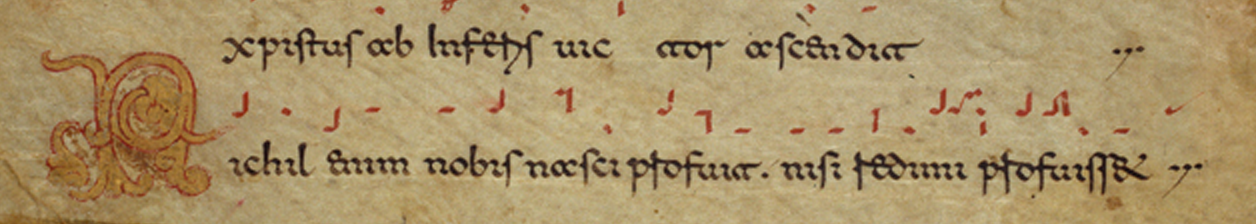

I am also intrigued by some of the notation systems that resemble letters and punctuation, such as this one from MS Lat Qu 44, and was curious as to whether musical notation might have inspired some of the VMS glyph-shapes:

I didn’t discover any convincing glyph origins in medieval music, but I did learn quite a bit about notation systems.

Jotting a Note

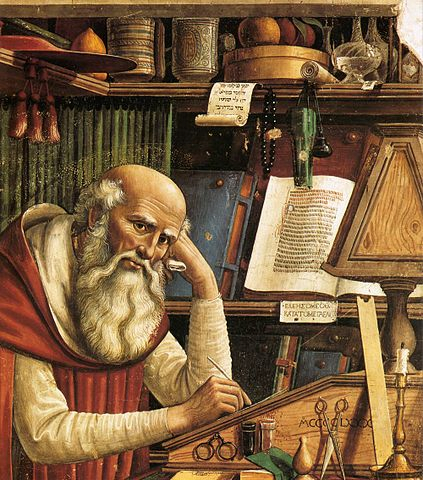

Detail of musical notation with five staff lines, vertical bars, the key signature, and arcs for phrases. This system is well-known to musicians throughout the world, but in the middle ages, music had not yet been standardized, and numerous staffed, staffless, and relative systems existed.

In modern western systems, the staff is an anchor for denoting a specific pitch, with the key signature providing a guideline to generalized sharps and flats.

The notes themselves follow conventions for duration (quarter note, half note, etc.), additional symbols specify the number of beats per bar, and curving arcs and <> symbols indicate phrasing and volume.

You could cut apart the music with scissors and still have a pretty good idea of how each part sounds.

Not every system works this way, however.

Some notation systems are based on the pitch distance from one note to the next, rather than an absolute system anchored within a staff. Ear-trainers teach intervals such as perfect fourth, perfect fifth, major thirds, minor thirds, etc. These are the distances between two notes. If you learn them, you can read certain forms of staffless music by following the interval from one note to the next based on the shape of the symbol rather than its vertical location on a set of lines. Other symbols function as modifiers to indicate duration or tempo.

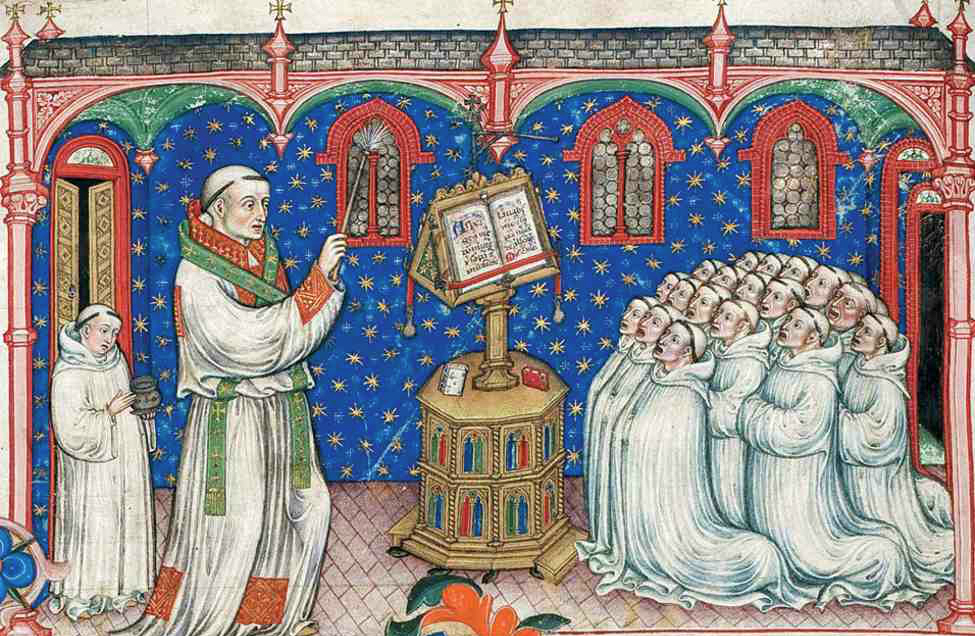

Systems like this were developed when instrument-making was primitive, and choral music was widely practiced as a form of worship or as entertainment. Relative systems were especially suitable for chants. If you’ve seen the Brother Cadfael series, you’ve heard the kind of music that was originally expressed in this kind of notation system.

You might notice in the example from MS 30337, that the symbols are rather squarish. Many of the earlier systems have this general look-and-feel. Systems with curves and lines (a phrase familiar to Voynich researchers) tended to come later, and sometimes included more symbols than their predecessors. Even so, many of them were comprised of about 15 symbols—less than typical alphabets.

Some systems included a symbol for the key of the starting note and others did not—you could choose whatever was most comfortable for the voices. In modern western notation, the entire set of notes is transposed to a different position on the staff lines to alter the key. In a relative system, only the starting symbol is changed and the rest of the notes follow from that.

From Music to Mystery Glyphs

One of the reasons relative-notation systems intrigued me is a certain “follow-along” feeling to the way VMS word-tokens are organized, with many of them being similar to those that go before them, often differing by only one or two glyphs. Torsten Timm has done some interesting work in trying to algorithmically model these characteristics of the VMS text.

There also seem to be rules about where certain glyphs can be placed in a VMS-word, a characteristic I’ve discussed in numerous blogs, and one that is integral to many relative musical notation systems.

Repetition and self-similarity are very common in VMS text, with certain patterns occurring in specific positions in a word-token. This kind of positional priority is also found in Roman numerals and relative music-notation systems. [Image credit: Beinecke 408, Beinecke Rare Book Library, Yale.]

Most western languages are not tonal (in the sense of a different pitch indicating a different word), but many African and Asian languages are, and writing the sounds requires extra symbols to indicate the tones. This is also done in musical systems. In staffed systems, different pitches are arranged in different locations on horizontal lines. In relative systems, the shift in tone can be indicated with an interval symbol, but can also be notated as ascending or descending (in other words, there’s more than one way to notate related concepts).

Not every musical symbol has a sound value, just as linguistic systems include symbols without sound values, like the apostrophe. While some relative-notation symbols inherently indicate the length of a tone by their shape or length, others may be modifiers (like the one just mentioned that doubles a note). Modern staffed systems also have their share of modifiers, such as symbols to indicate the quality of a sound (e.g., pizzicato or staccato).

Byzantine Musical Notation

I don’t know Byzantine notation well enough to sing it aloud. There is a long set of rules for how the symbols may be combined and it takes practice to read it, just as sight-reading modern notation takes practice, but I am familiar with some of the basic terminology, a few of the symbols (known as neumes), and the concepts of relative notation that I learned from other musical systems, which apply in the same way to Byzantine systems.

For example, there is a small bowl-like symbol that is written together with tonal symbols to prolong the beat, just as there is a symbol for doubling the beat (playing it twice rather than prolonging it). Once again, this idea could be applied to linguistic notations. In English we typically double the following consonant if we want to shorten a vowel. Thus, the long-a in pater becomes a short-a in the word patter, but imagine if a common symbol were used rather than a letter, one that could be used throughout instead of a dozen different doubled letters—a certain economy of shapes is characteristic of relative notation and of the VMS.

The following example of Byzantine notation is from a manuscript in the British Library. Note how the symbols are curves and lines written in a linear fashion rather than flowing up and down on a musical staff.

I mentioned curves and lines because the VMS character set is unusual in having a strong emphasis on curves and lines, with many of the glyphs appearing to be composites of a few basic shapes.

Since relative systems were strongly tied to choral chants, and humans typically sing one note at a time (with Tibetan throat-singing being an exception) it wasn’t necessary to indicate simultaneous notes on a staff in the same way as one might for an instrument with several strings that are strummed at once.

This sample of Byzantine music illustrates how notes are expressed relative to one another with a concise set of basic symbols, rather than being laid out as ovals on a musical staff. Note that some of the symbols are drawn in red, like the ell-shape that resembles Greek gamma. This is called a gorgon and there are rules for whether it is placed above or below the associated symbol, just as the VMS has rules for whether a glyph appears at the beginning, middle, or end of a token, and additional rules for its associate-glyphs.

Now imagine if you were to transliterate this musical notation into an alphabet system. One might take a symbol like the gorgon and place it before or after its associated symbol, rather than above or below. This calls to mind the highly frequent “o” symbol in the VMS, which is often at the beginnings of V-words, and frequently precedes EVA-t or -k. Note also that this notation system is very rule-based and would exhibit many positional characteristics if rendered as text.

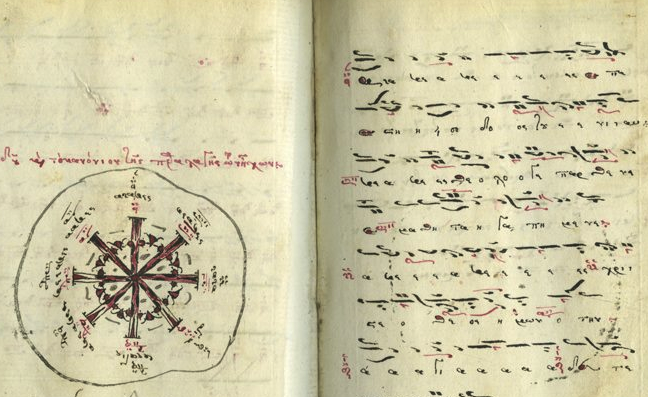

Byzantine music was documented in this 18th-century Serbian manuscript held in Greece (Schoyen MS 1897) and I include it because a variety of whorled diagrams were not uncommon in books of music.

There was a particular interest in relating “music of the spheres” to cosmological concepts in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, so some of the whorled and wheel-with-spokes images reflect these ideas, and the shapes became iconic designs found in many music manuscripts to describe these and other concepts. Wheels were also used to illustrate a variety of tonal systems.

There was a particular interest in relating “music of the spheres” to cosmological concepts in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, so some of the whorled and wheel-with-spokes images reflect these ideas, and the shapes became iconic designs found in many music manuscripts to describe these and other concepts. Wheels were also used to illustrate a variety of tonal systems.

In fact, it doesn’t surprise me that composer Edward Elgar chose symbol positions for his Dorabella cipher that appear to rotate through eight angles, the same number of tones as in a basic western scale (do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti, do).

Summary

There was a large body of relative notation in the early middle ages, but musical instruments improved (along with our ability to play them) and the staff system (which could more readily accommodate simultaneous multiple notes), gradually superseded it. The algorithmic quality of relative notation was almost forgotten.

I know that people have assigned notes to the VMS glyphs and played them as music (I’ve done this myself), but relative notation isn’t about assigning a tone or chord per glyph, it’s a prioritized system describing tone, duration, direction of the pitch, and nuance, and the modifiers are applied in a certain order (and sometimes change based on what is being combined). When you scan it visually, it is concise, repetitive, and positional, as is Voynichese. It’s the closest analogy I’ve seen to the structure of the VMS text, and I wasn’t even planning to mention it until I had more time to explore it, but extra time doesn’t seem to be coming my way.

————— = + = —————

The frequent repetition in Voynichese is somewhat reminiscent of songs or verse, but there’s something more to it—even songs and verse have more positional variety than VMS glyphs.

Relative notation systems range from simple to very sophisticated, but many of the more sophisticated ones can be expressed in about 10 to 20 symbols, depending on how they are placed. In other words, the musical “alphabet” can be written with a smaller character set than many human alphabets.

What if the VMS were the notes themselves, rather than lyrics, lists, or narrative text, or were a constructed language built on the same concepts as relative musical notation, where one-to-one correspondence doesn’t apply, where modifiers determine how a glyph should be read?

What if the VMS were the notes themselves, rather than lyrics, lists, or narrative text, or were a constructed language built on the same concepts as relative musical notation, where one-to-one correspondence doesn’t apply, where modifiers determine how a glyph should be read?

Perhaps one of the glyphs is like the petaste, a symbol that represents a one-step tonal ascent. Imagine a symbol that says, “Don’t read the previous glyph as t, read it as the letter that follows it in the alphabet.” Or imagine if gallows-k meant something different depending on whether it’s followed by EVA-y, or ch or ol or od (Janus Pairs).

Many of the ideas common to relative musical notation have direct analogs in the cipher world and since chants were popular in monasteries, as was the development of ciphers, monks monks may have transferred some of these ideas from one to the other as the old notation systems faded away.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2017 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved