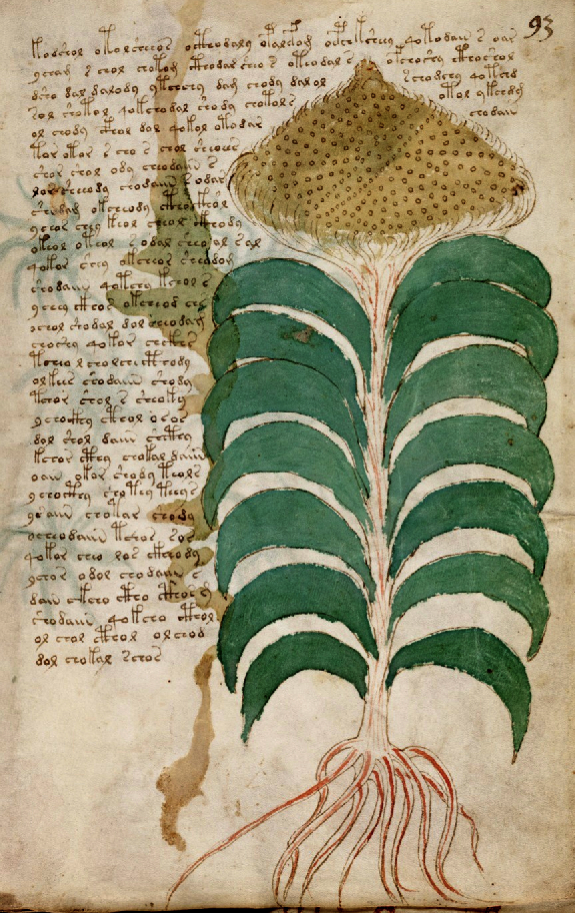

In 2007, when I first encountered the VMS, I paged through the plants, over and over, to see if they were drawn according to a personal formula. What did the illustrator consider important? How accurate were they? How were certain features expressed? Could the colors be trusted? Was Plant 93r a sunflower?

After almost a year of study, I had a better sense of how the illustrator approached certain details and had learned to respect the drawings. In my opinion, the naturalistic drawings (there are quite a few of them, mixed in with some that are more stylized), are reasonably accurate, even if the drawing skills are modest.

I noticed that the leaf margins, and the general shape and arrangement of the leaves, is quite good, making allowances for mnemonic exaggeration. The colors of the leaves also seemed to be reasonably good. The only part that seemed consistently questionable was the color of the flowers, at least it seemed that way until I realized some of the drawings might have been drawn from dried plants (e.g., blue flowers often turn to brown or yellow as they dry) and some appear to have gone to seed. I suspect that blue might be used symbolically to represent seeds (I’m not completely sure, and even if it’s true, it might not be true for all of them).

That’s when I began trying to identify the plants, including the one on folio 93r.

To this day I am not entirely sure how naturalistic the roots are intended to be. Just as some plants have leaves that appear to be mnemonic, some of the roots seem to be also (although it’s possible to be both somewhat naturalistic and mnemonic at the same time). I decided to trust the shape of the roots as naturalistic if there were no obvious animal, cultural, or anatomical imagery incorporated into them.

The Identity of Plant 93r

In 2013, when I originally planned to post this blog, there were very few public domain illustrations I could use to convincingly illustrate alternate plant IDs. That situation has changed, so it’s time to get it finished.

In 2013, when I originally planned to post this blog, there were very few public domain illustrations I could use to convincingly illustrate alternate plant IDs. That situation has changed, so it’s time to get it finished.

Edith Sherwood stated up-front that she considered the Voynich Manuscript, “…a 15th century Italian manuscript” and that she and Erica’s plant IDs were limited to “plants native to Europe or at least the old world and excluded all plants from the Americas”. In other words, the sunflower, a plant that was introduced to the Old World in the early 16th century, was explicitly excluded by the Sherwoods as a possible ID for this plant. But that didn’t stop others from proposing it.

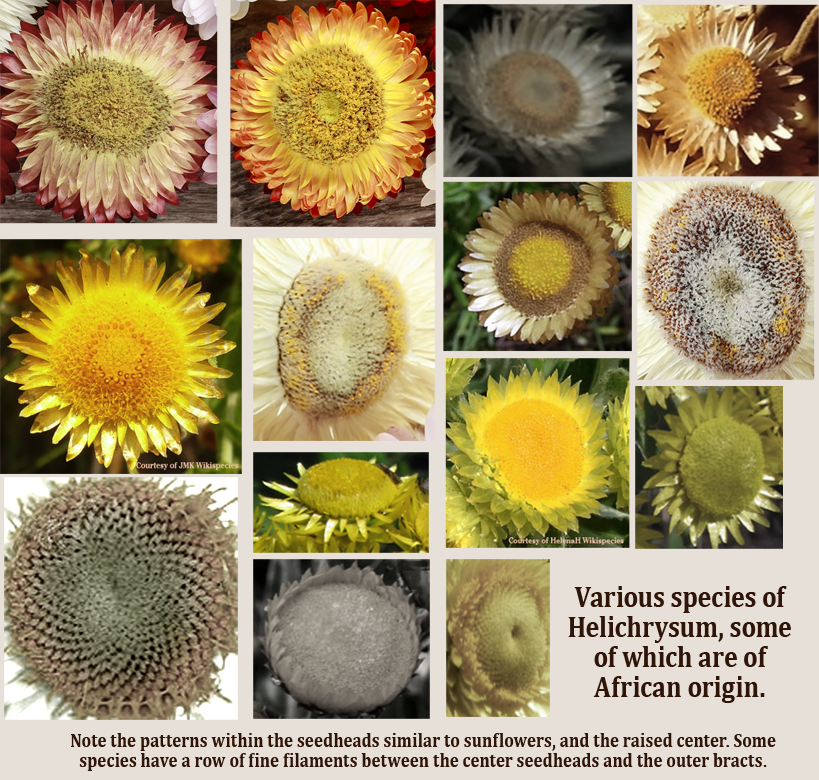

I didn’t really care whether it was an Old World or New World plant. Evidence would eventually settle that question, and it made no difference to me how many others had apparently insisted it was a sunflower, I simply researched as much as I could about the history and distribution of sunflowers and sunflower-like plants. The reason I was unwilling to commit to sunflower is because certain species of Chrysanthemum, daisy, or Helichrysum resemble sunflowers if imperfectly drawn or examined at a different scale.

I don’t think anyone can say for certain that this is sunflower, including botanists who seem adamant on the point. The fringe surrounding the seedhead is very fine compared to the triangular bracts that ring most sunflowers, and sunflowers with large seedheads often have tuberous roots that are lumpy, like ginger, not tendril-like, as in the VMS drawing. The leaves aren’t typical for sunflowers either, although there are some species with longer, more lanceolate leaves, but they tend to be the ones with longer petals in relation to the seedhead.

Leaves and Stalk

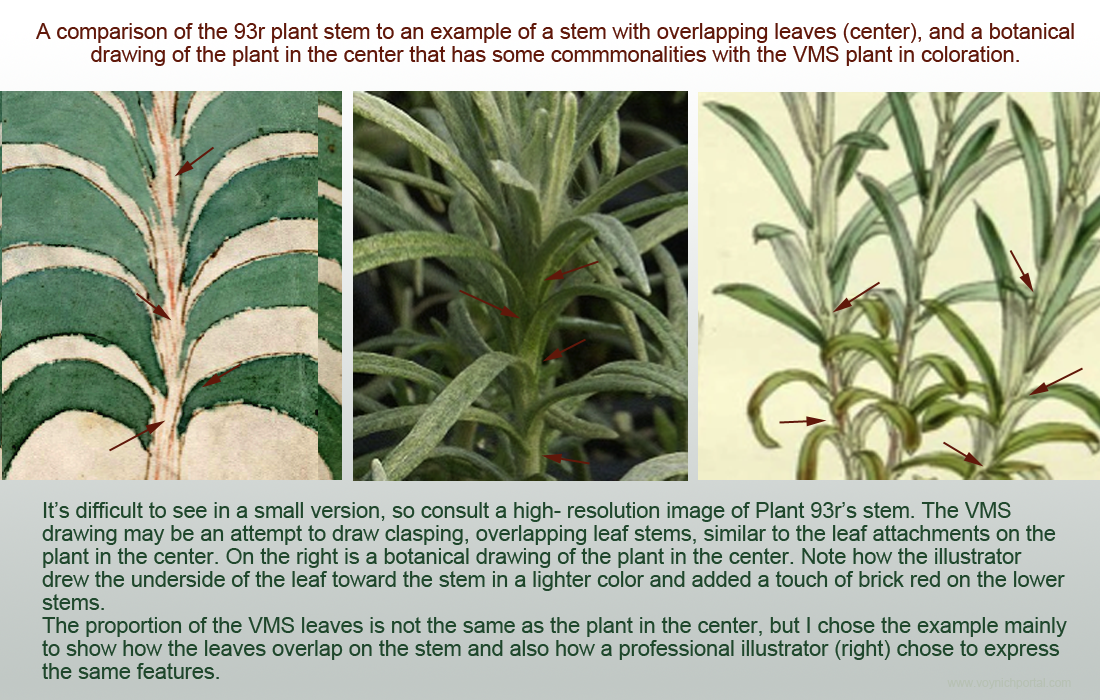

Find a high-res scan and look very closely at how the VMS leaf attachments and stalk are drawn. I’ve never seen anyone comment on this. Occasionally they mention the shape of the leaves, but not how carefully the illustrator has laid the short petioles against the stalk so that they appear almost to overlap. If you were to “flatten” this plant the way the VMS plant has been flattened (note that all the leaves go to the sides—it’s not a 3D arrangement), the VMS illustrator may have been trying to draw the kind of leaf arrangement illustrated on the right. This is not easy for someone with limited drawing skills:

Note also how the botanical drawing on the right shows lighter undersides on the leaves, a trait that is more apparent near the stem. There are some light touches of brick-red on the lower stems. This is because stems like this are often more “woody” and darker near the base (this is seen on many species of plants).

Note also how the botanical drawing on the right shows lighter undersides on the leaves, a trait that is more apparent near the stem. There are some light touches of brick-red on the lower stems. This is because stems like this are often more “woody” and darker near the base (this is seen on many species of plants).

The leaves of Helichrysum, like the flowers, can be quite variable, but some species have slimmer, longer leaves than sunflowers. Note how the one on the left is close to the stem and almost overlapping and quite similar to the way the VMS leaves are drawn near the stem. The second illustrator (middle) chose to draw the leaves splayed out, with a reddish stem. The VMS drawing seems to fall somewhere in between:

Bracts, Petals, and Seeds

The shape of the sunflower seedhead may seem unique, but it’s only the large scale that creates this illusion. In fact, this form of seedhead is widely seen in the aster family.

These examples demonstrate that Helichrysum (as one option) would look significantly similar to Helianthus (sunflower) if drawn by an illustrator with limited skills:

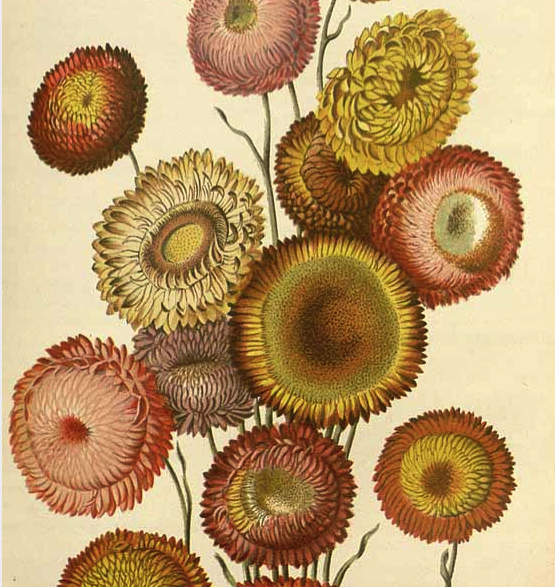

Here are botanical drawings of two different species of Helichrysum, one with long stalks, another with shorter branching stalks (sunflowers also come with both kinds of stalks):

Helichrysum grows worldwide, but several species are native to Africa. Some of them are from the Cape region and would not have been known in central Europe in the early 15th century, but others are from coastal Africa and the Mediterranean and might have been imported to Europe as a medicinal plant. Even today, Helichrysum is sold as an essential oil.

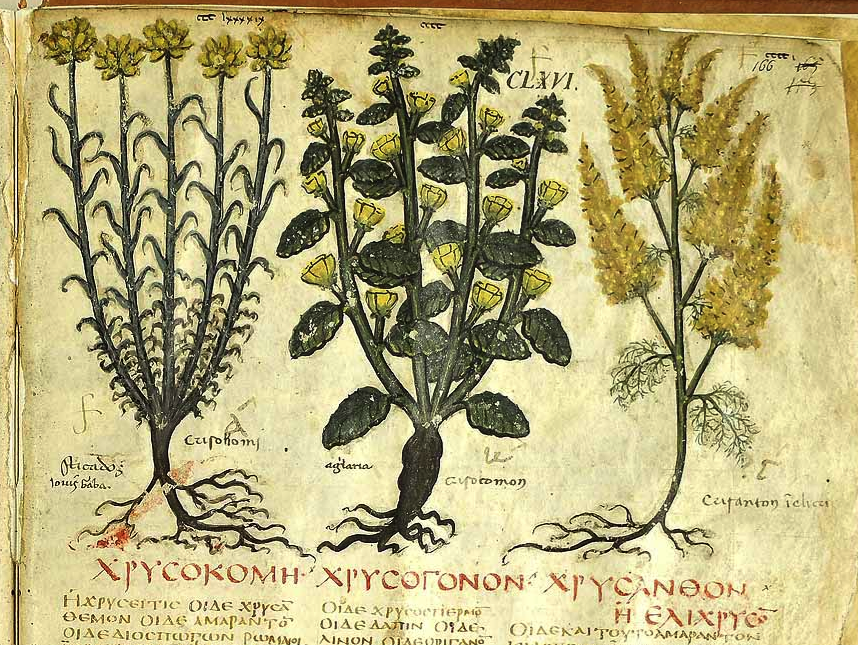

If you’re wondering if Helichrysum and other asters were known in the Middle Ages, the answer is yes. Chrysokomi, Chrysogonon and Chrysanthon were documented in early copies of Dioscorides, and some of the late medieval botanical drawings refer to some species of Helichrysum as Gnaphalium (the sunflower is also in the Compositae (aster) family):

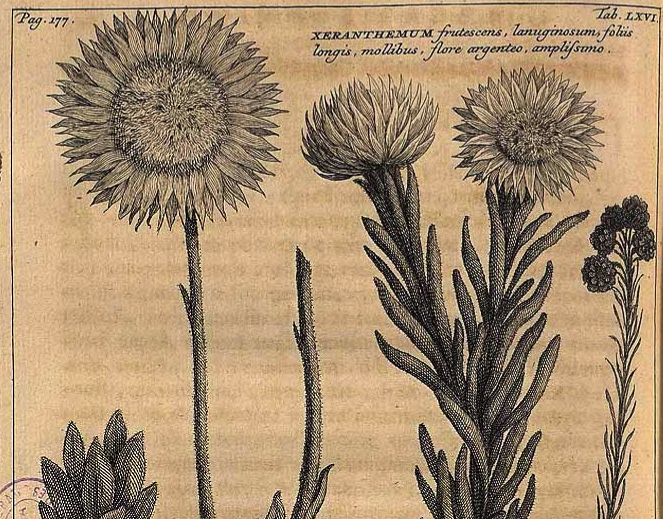

You might also recognize the name “Xeranthemum” as similar to Chrysanthemum (many sunflower-like plants, including the sunflower itself, were sometimes referred to as Chrysanthemums in early published botanicals). This “Xeranthemum” is an African cousin to the Carlina thistle (Carlina is mentioned in numerous medieval herbals):

You might also recognize the name “Xeranthemum” as similar to Chrysanthemum (many sunflower-like plants, including the sunflower itself, were sometimes referred to as Chrysanthemums in early published botanicals). This “Xeranthemum” is an African cousin to the Carlina thistle (Carlina is mentioned in numerous medieval herbals):

Summary

There are other possible IDs for Plant 93r and unfortunately I don’t have time to post all my data or hunt for suitable pictures, but the point I wanted to make is that the VMS drawing does not have to be a sunflower. I’m not completely ruling it out, but the bracts seem rather small and narrowly spaced for Helianthus, and the leaves too narrow for the species of sunflowers that have larger seedheads, so the ID can certainly be challenged.

It could be Helichrysum, or perhaps one of the other asters with prominent seedheads in proportion to their overall size (the gerbera daisies come to mind), but it makes no sense to insist that it is sunflower as long as there are other plants that resemble the VMS plant as well or better.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2 October 2018 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved