19 April 2019

There are two pattern groups in the VMS that could be related, maybe. They have traits in common that might help us understand Voynichese.

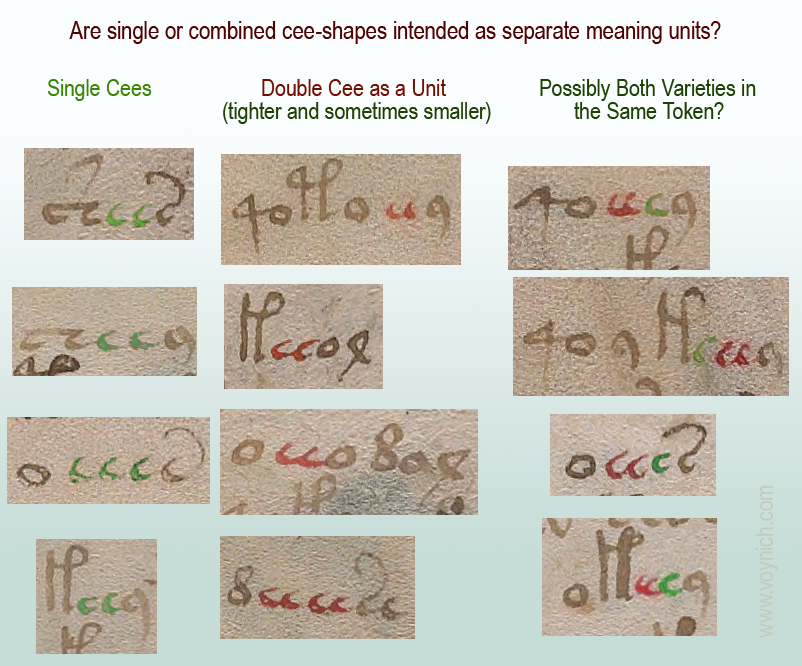

I’ve blogged about double-cee shapes (EVA-ee), but felt it would be too long if I included relationships between cee patterns and the more familiar aiin patterns, so I’ll continue the discussion here…

The Double-Cee Question

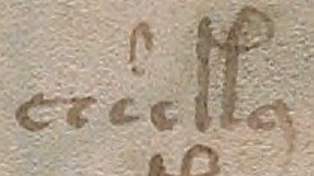

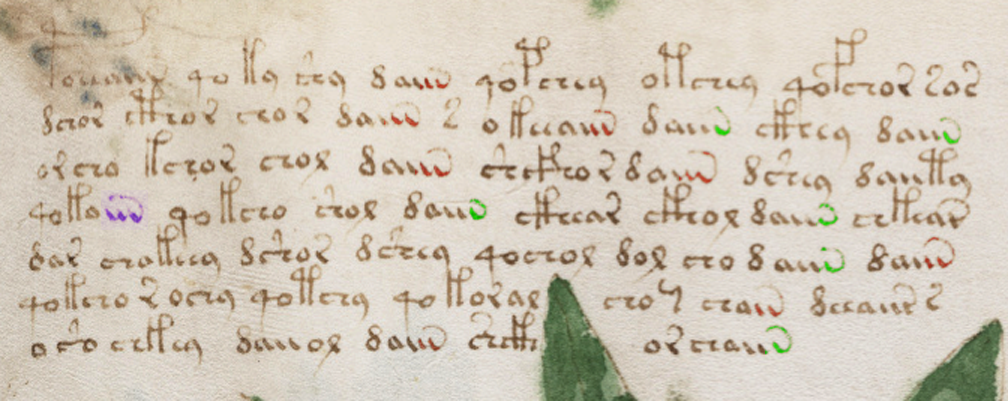

As I’ve posted before, there are many places in the VMS where cee shapes (EVA-e) look like they might be joined. There are even places where double-cee and single-cee are adjacent:

I strongly suspect that double-cee (the one that is tightly coupled) is intended as one meaning-block.

- In Visigothic manuscripts, the letter “t” was often written as a double-cee shape.

- In early and mid-medieval manuscripts, a double-cee stood for “a”

- In early and mid-medieval manuscripts, a superscripted double-cee stood for what we would call “u” (it was often next to a “q” character).

Thus, many scribes perceived tightly coupled cees as a unit.

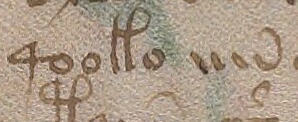

Of course, nothing is easy with the VMS. Here is an example of overlapping cee-shapes next to ones that are separate. Do we interpret them as different or the same?

Note also how the bench joins with the row of connected cees, which brings us to the next point…

Is The VMS Deliberately Deceptive?

It’s very difficult to tell if the VMS is designed to deceive. Patterns like the following are hard to interpret.

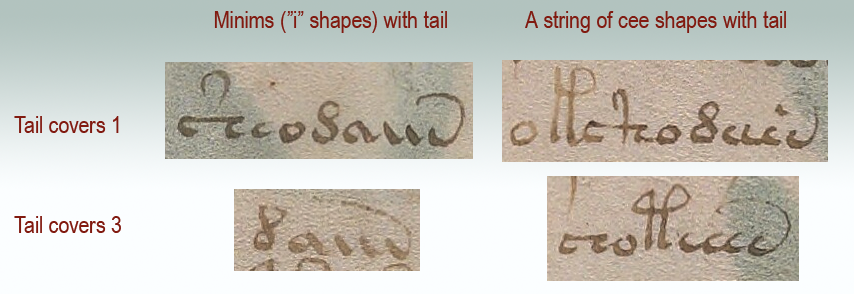

Are the tails on these glyphs added to hide the length of a sequence? Or are they genuinely different glyphs?

In the same vein, are EVA-ch and EVA-sh cee-shapes in disguise? Could the cap on EVA-sh be yet another cee?

Here’s an example where two cee-shapes are topped with a macron-like cap (a shape that is usually associated with the benched char):

For that matter, is the 9-shape a hidden cee?

I don’t know for sure, but based on the behavior of the glyphs (in terms of position and proximity), I get the feeling (so far) that EVA-ch and EVA-sh might be related to cee-shapes, even if they mean something different (they frequently occur together), while EVA-y dances to a different drummer.

Positionality

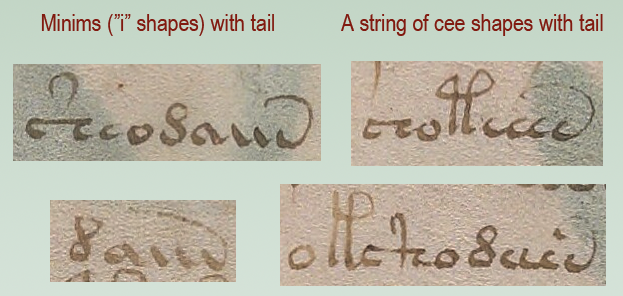

Cee shapes frequently cluster in the middles of tokens, just as minim patterns are frequently at the ends, but are they somehow related? They are the only two groups of glyphs that repeat many times in a row.

These examples from f4v and f7v are provocative because they suggest that cee shapes and minims might be related. Rather than being word-medial, the cees on the right are word-final and have long tails from the bottom rather than the top:

Now, let’s examine the -aiin patterns…

Aiin not Daiin, and maybe not even Aiin

I think it was a big mistake for early researchers to cinch the idea of “daiin” in people’s minds. The aiin sequences are frequently (yes, frequently) preceded by glyphs other than EVA-d.

Stephen Bax wrote a paper in 2012 (revised Nov. 2013), in which he summarized one of the most common ideas for interpreting the glyph sequence called “daiin” (e.g., that it might mean “and”). Here is a quote and a link to the PDF file:

It is argued from this analysis that the element transcribed as ‘daiin’, the most frequently occurring item in the manuscript as a whole, is in fact a discourse marker separating out sense units, functioning like a comma or the word ‘and’, and analogous to the use of crosses in folio 116v.

Stephen Bax

The Voynich manuscript—informal observations on some linguistic patterns.

And here are some of my observations…

First, let’s start with the crosses on folio 116v. There is a strong precedence in medieval manuscripts for including the plus sign in charms and medical remedies in places where the reader or speaker (or healer) genuflects. The plus sign is sometimes also used like “and”, just as we use it now (nothing new about that). However, I doubt that the plus- or cross-symbol on 116v is related to “daiin”.

Now back to the paper…

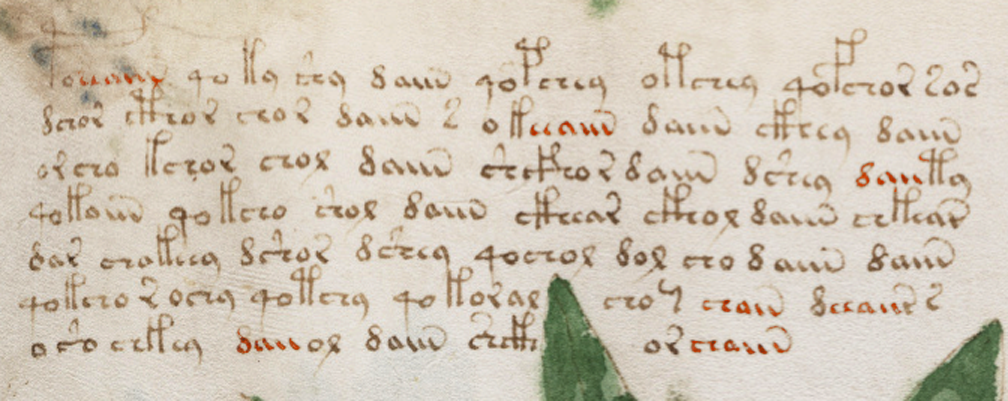

On page 3, Bax noted instances of word-final daiin, but he examined them out of context. He recorded instances of aiin that are preceded by EVA-d and basically ignored the other glyphs that precede -aiin in the same sample (as well as daii- that occurs at the beginning). I have marked the patterns that were not mentioned in red:

Studying the “daiin” pattern this way is like examining -tally patterns in English while ignoring related patterns like -ly, -lly, -ally, -aly, and -dly. He also failed to account for the fact that aiin is not a homogenous glyph pattern. It includes an/ain/aiin/aiiin and even sometimes iiin.

He further makes no mention of the tail patterns. If the length of the tail is meaningful then, like so many before him, Bax might have overestimated the frequency of daiin.

Tail Coverage

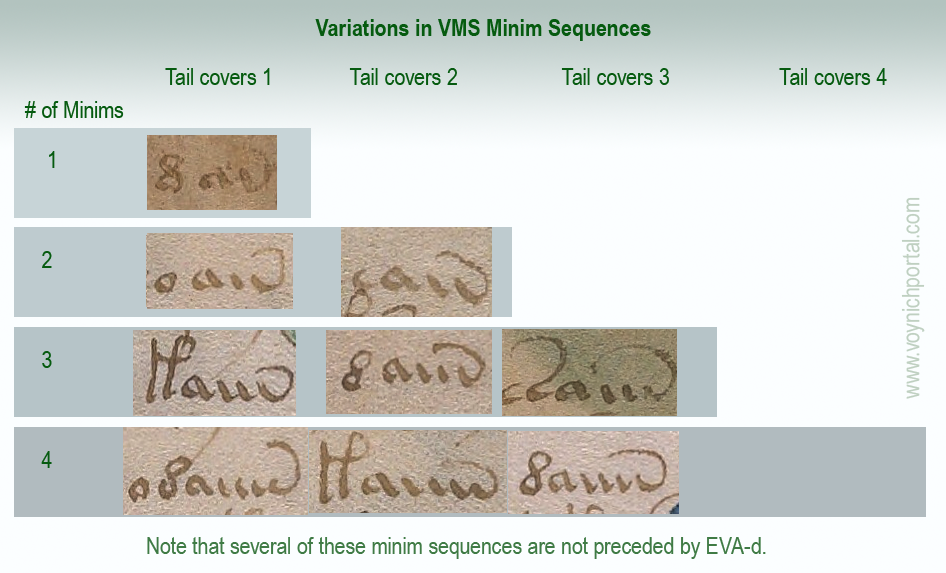

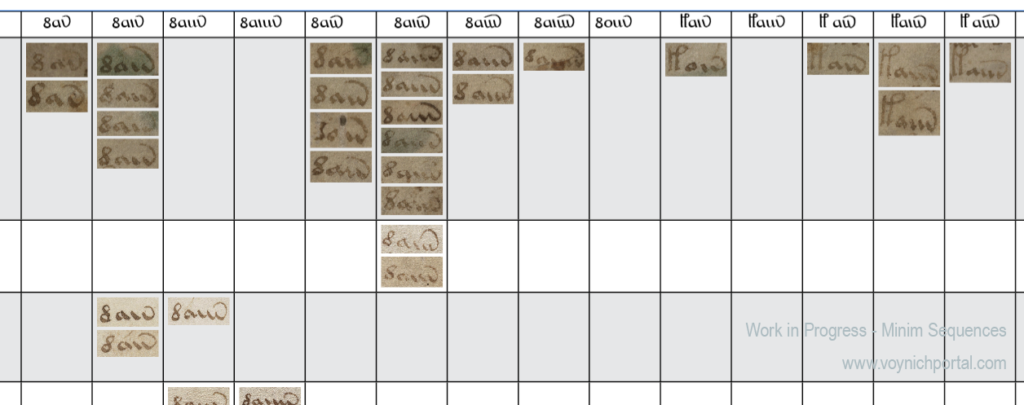

Most transcripts treat the many versions of daiin as if they are the same. They count only the number of minims (and they don’t always get that right). But there is another dynamic that gets little attention, and that is the length of the tails.

Tail coverage varies. Thus, a glyph with three minims might have three different versions of tail coverage and perhaps three different meanings:

Here is the text sample color-coded for different tail patterns, with green for one and red for two:

About half the instances of “daiin” look like dauv and the others look like daiw, if you pay attention to the length of the tail. They are not necessarily the same. If you include aiin sequences not preceded by EVA-d, it varies even more. Normally I wouldn’t consider tail length to be important. In Latin, the length of tails (a form of apostrophe or ligature) is pretty arbitrary. Some scribes lengthened the tail if more letters were left out, but this was not the norm. In the VMS, when you create a transcript and examine every token, tail-length feels deliberate.

Nick Pelling pointed out to me in a blog comment that there are dots at the ends of tails. I’m not sure I had noticed that (he’s right, there are). I had noticed the varying tail lengths. After Pelling called my attention to the dots it occurred to me that maybe the dots were to help the scribe accurately craft the length of the tail.

Tail lengths might turn out to be trivial rather than meaningful, but it’s still important to document their patterns as part of the research process. If they are significant, then vanilla-flavored “daiin” is not nearly as frequent as claimed.

Forget about the “d”…

Minim sequences don’t require EVA-d and don’t always need EVA-a. Here’s a minim sequence that stands alone (four minims with one covered, or perhaps three minims and another glyph entirely):

I think future research would be more fruitful if transcripts and descriptions of the text were more aligned with reality. Calling them minim sequences carries fewer assumptions than “daiin”.

Interpreting Minims

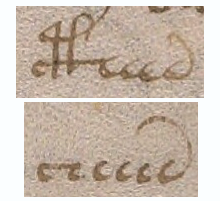

I’m not sure minim sequences are intended as separate characters. Just as some of the cee shapes look like they belong together as a block, the iii sequences do so as well. There are numerous instances where they resemble uiv rather than iiv.

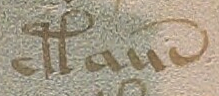

In this example from folio 8r, a curved macron has been placed over two minims in aiiin (I prefer to call the shapes aiiiv rather than aiiin, but I’ll respect the existing EVA system for now). It is almost as though the scribe were explicitly associating two minims:

Maybe the cap is a macron in the Latin sense (apostrophe for missing glyphs), or maybe it’s a way to say, this is a “u” shape, don’t confuse it with “ii”. Note that there is a slight gap between the first “u” shape and the second (or between the “u” shape and the “iv” shape):

In this example from f8v, the first two minims resemble a “u” shape and are distinctly separated from the final glyph (which resembles “v” or “i-tail”, and yet there is a 3-coverage tail):

As for the length of the tail, in Latin it usually doesn’t matter, but there were a few scribes who pointed the tail at the particular spot where letters were missing (the tail is an apostrophe attached to the end so the scribe doesn’t have to lift the quill). What it means in the VMS is still a mystery.

Maybe progress in understanding the VMS is slow because many transcripts don’t include these details.

I have an enormous chart that documents these patterns, but it’s not yet finished and ready to interpret. This is only the merest snippet—part of the top-left corner:

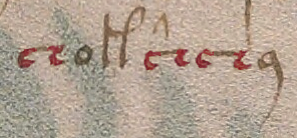

Minims and Cee Shapes

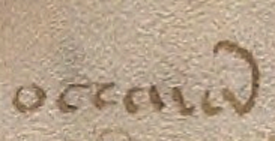

This is getting long, so I’ll end with one last question (possibly an important one). Is there some connection between minims and cee shapes?

Minims are more frequently at the ends of tokens (but not always). Cee shapes more often in the middle. Both tend to cluster. Both have tails of varying lengths.

It’s fairly obvious that they both repeat, but I don’t know if anyone has offered a practical explanation (other than the possibility of Roman numerals). Here are examples that illustrate the similarities:

And here is an example that is particularly enigmatic. Is it EVA-ochaien or EVA-ocheiien or ochaiin or something else? Did the scribe slip and draw one of the minims as a cee-shape, or is this a uniquely structured token?

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2019 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved