8 August 2019

Back in July 2016 I posted a short blog about some of my early ideas for the VMS “map”. My favorites in the early years were Jerusalem (this was actually my first idea); Villa d’Este; the Naples/Sicily volcanic area; the natural-spa areas in northern Italy/Germany/Czech; and one I haven’t disclosed yet because I want to write it up properly with pictures and I haven’t had time to do a proper job.

There are others, but these are the ones I particularly liked and spent considerable time investigating.

1) Jerusalem

I spent countless hours studying old paintings, engravings, postcards, and aerial photographs of Jerusalem. My reasons were simple:

- The top-left rotum in the VMS “map” is oval (olive-shaped) and looks like a mountain (I thought it might be the Mount of Olives),

- the center rotum has lots of towers (the traditional position and way to depict Jerusalem),

- there was a tradition of building tombs into the hills next to paths, which means that some of these old tombs look like towers in holes (you have to look at very old images to see this because all the paths have been widened since medieval times and they look less like they are in holes), and

- pilgrimages to Jerusalem were customary and thus a journal-style “map” with landmarks would be appropriate to the time.

After studying Jerusalem so extensively that I could walk around it in my head, I was beginning to think I might be wrong or at least that I should not get too invested in one idea, and that I should take some time to investigate other ideas.

One of the next items on my list was Villa d’Este, which is an astonishing piece of medieval/renaissance hydraulic engineering, partly inspired by old Roman ruins and earlier water gardens that were not quite so elaborate. The engineering was so advanced that sensors would detect the presence of visitors and turn on the sprinklers to give them an unexpected shower.

2) Villa d’Este

Even though I was worried that the construction of Villa d’Este was too late to have inspired the VMS (even back in 2008 I pegged the VMS in my mind as 14th or 15th century, mainly for palaeological reasons), I thought if I learned everything I could about it, maybe I could discover an earlier water garden with the same properties that might be connected to the VMS. Here is what intrigued me about Villa d’Este:

- It is overtly Pagan, filled with pools, fountains, and statues of nymphs, echoing the profusion of nymphs and water in the VMS. Remarkably, it was built by a Christian cardinal who showed no remorse whatsoever when his colleagues criticized him for his choice of Pagan themes.

- There is a spiral staircase in the main structure (and a spiral on the VMS “map”).

- It has many topological features in common with the “map” folio and VMS pool folios, including waterfalls, fountains, natural pools used for swimming, a winding path leading to the estate with an ancient round Pagan temple, and many other features that seem to match the VMS drawings.

- There is an extensive herb/kitchen garden and surrounding gardens, which might have been documented at some point in time.

In other words, some connection with the Villa d’Este or its predecessors could explain numerous features on the VMS “map” and also the many pool drawings and nymphs in other parts of the manuscript, and possibly even the plant folios. You can almost chart a path around the estate lands and match them up with the landmarks on the VMS “map” folio.

I also spent time investigating the d’Este family tree to see if water gardens existed in the earlier generations of the family.

I became so familiar with Villa d’Este from photos, postcards, paintings, Google Earth and aerial photos, that I could walk around this in my head, as well, and I was reluctant to let go of the idea except that I had another one that seemed equally intriguing…

3) Naples/Baia/Sicily/Salerno Volcanic Region

This is one of my favorites. I’ve blogged about it several times. After becoming so familiar with Villa d’Este that I felt I had been there, I dove into a more in-depth study of the Naples/Salerno/Baia region. It caught my attention for the following reasons:

- Vesuvius has an eye-shaped crater (similar to the “mountain” top-left on the VMS map). The wavy lines in the eye-shape might be flames, thus indicating a volcano, or they might be water filling in a dormant crater, or they could represent the famous Sulphurata/Solfatara, Campi Flegrei, all of which are present in the Naples region.

- Medieval medical students from areas like Paris and Heidelberg frequently spent part of their university career in Naples or Salerno studying plant medicine and astrology, and might document the journey as a map.

- The baths of Pozzuoli were located here (until they were destroyed by an eruption in 1538) and might account for the bathing nymphs in other parts of the VMS.

I have been to Naples. Unfortunately, it was an ill-fated trip. On the day I arrived, the museum staff went on strike and judging by events later in the day, it was not likely to end that day or any day soon.

There are numerous other commonalities with Naples that I’ve already covered and I won’t repeat here because the direction of this blog is related to more recent events. But before getting to that, there is one more location that I studied before moving on to other subjects…

4) Rome

I thought the way the VMS rota were organized, in separate circles connected by pathways, might be inspired by the hills of Rome. Rome is sometimes in the center of mappae mundi, rather than Jerusalem, and we have the saying, “All roads lead to Rome”, so I thought it might be possible to relate the VMS map to this area.

After some effort, I couldn’t get the topological features to fit as well as they did to Villa d’Este or Naples/Baia, but it seemed worthy of consideration. I tried the same with Paris, Venice, Genoa, the Flanders coast, and the Po estuary, with mixed results. They didn’t fit as well as Naples.

5) Natural Spas

In Greece, Italy, Croatia, Germany, Switzerland, and Austria, and numerous other places, there are natural spas with thermal pools, waterfalls, green pools, blue pools, grottoes and numerous features in common with the VMS.

I was overwhelmed.

I discovered there might be hundreds or thousands of areas that could match the VMS map if it documented a natural-spa area. This was bewildering, and very difficult to investigate because the topology of natural spas in the Middle Ages is not well documented. Plus, many of them have been over-built with modern spas and the original geology altered.

I gave up. The task was too difficult, so I confined my studies to a few of the ones that were popular retreats for medieval nobility, one of those being Tuscany (described in a previous blog due to the marble escarpments that look similar to features in the VMS “map”). I haven’t had time to write up the others.

I’m not going to describe #6 yet because it deserves a blog of its own and I don’t want to disclose the location until I can do a good job of it.

On to the point of this blog…

Recently, I’ve had to re-evaluate my assumptions about the VMS. The process of re-organizing my thoughts started more than three years ago, but it took a long time for the mounting evidence to convince me I might be wrong about the “non-Christian” nature of the VMS…

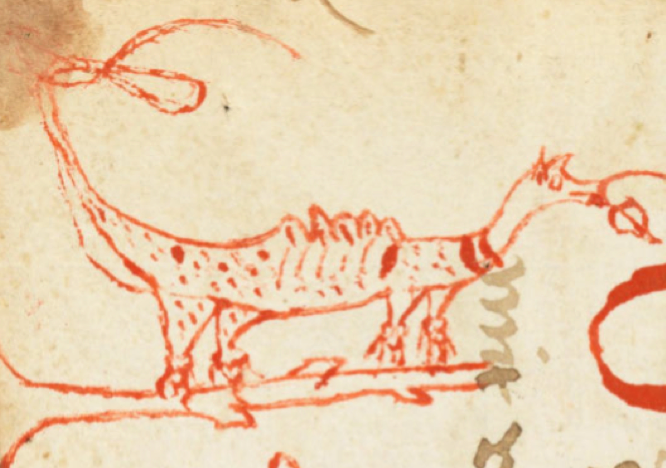

The Impetus of the Mystery Critter

In March 2016, I was inspired by comments by René Zandbergen and K. Gheuens to consider that the critter on f79v might be a golden fleece. The curved posture was the key feature provoking my interest. The blog is here.

Then in April 2016, when I was writing about Theriac, I thought, what other possibilities are there?

Perhaps the head-down posture and “scales” of the mystery critter might be a reference to the castoreum beaver, an animal that shows up regularly in medieval herbal manuscripts and which is often drawn very badly (it usually looks more like a dog, a deer, or a platypus than a beaver, and is frequently drawn with a scaly tail). Here is a link to that blog.

In other words, I was trying to think of as many explanations as possible and then hoped to find other elements on the folio confirming one of the guesses.

So what did we have? Armadillo, Pangolin, Sheep, Fleece, Beaver, etc., and somewhere along the line I also suggested an aardvark (no one seemed to like that idea but I’ll keep it on the list because they confused pangolins and aardvarks in the Middle Ages due to their similar habits and habitats).

Then I went through medieval imagery for each animal, one-by-one, trying to figure out how each one was traditionally drawn and why, and collected as many examples as I could find.

By 2018, I had more than 2,000 medieval images of sheep. That might seem like a good starting point, but the ones that related best to the VMS were the ones I had been reluctant to collect.

Baaaaaaaa…d

The irony (which will become clear further down) is that I didn’t collect most of the Christian-themed sheep I came across, even though they were in the majority, because I didn’t think the VMS was a Christian-themed manuscript. About 70% of my samples were from secular or zodiac sources (some of which are only incidental embellishments in Christian manuscripts and were not directly illustrating Bible stories).

Then came the eye-opener, which hit me sometime in late 2018, and which I blogged about in April 2019 (the “zoomer” post I lost and had to repost) and another in June 2019… the imagery surrounding the mystery critter (cloudband “cushion”, lines, etc.). Like it or not, the critter’s milieu was more similar to Christian imagery than the others.

This took me by surprise. I thought, “Could I have been wrong all this time? A dozen years of studying this manuscript and I’ve been discounting the possibility of Christian content.”

Of course then I kicked myself because I TRY to search with as few assumptions as possible.

So where is this leading?

It’s leading to interpretation. But first, let’s get short-sightedness out of the way first…

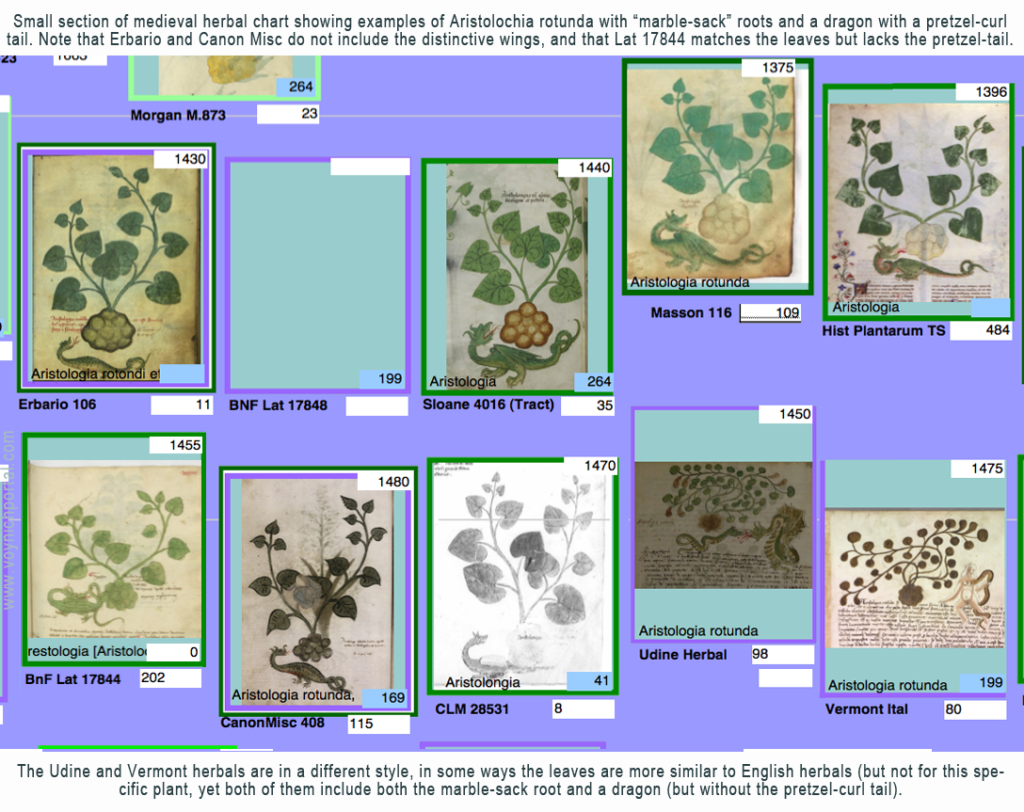

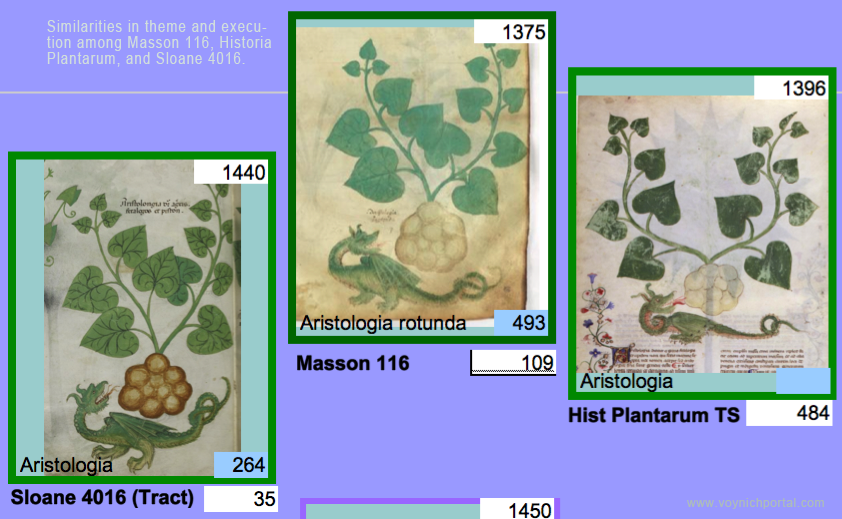

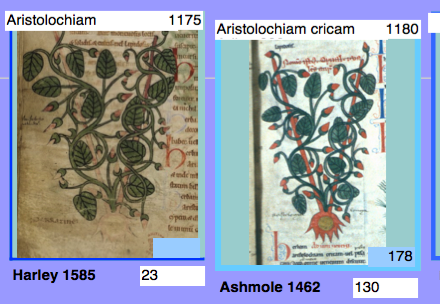

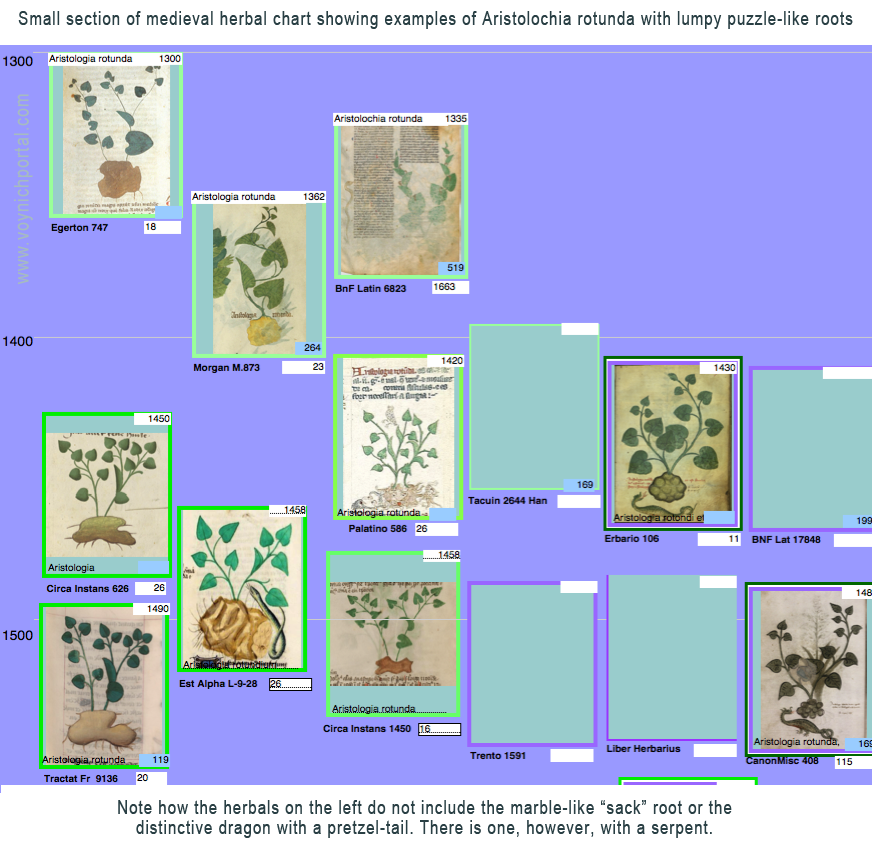

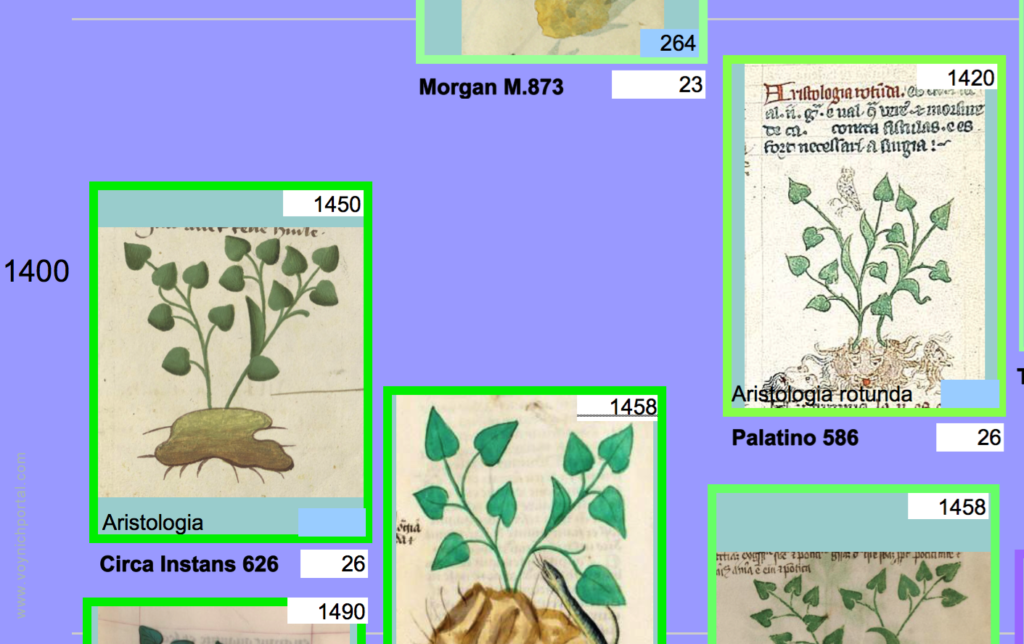

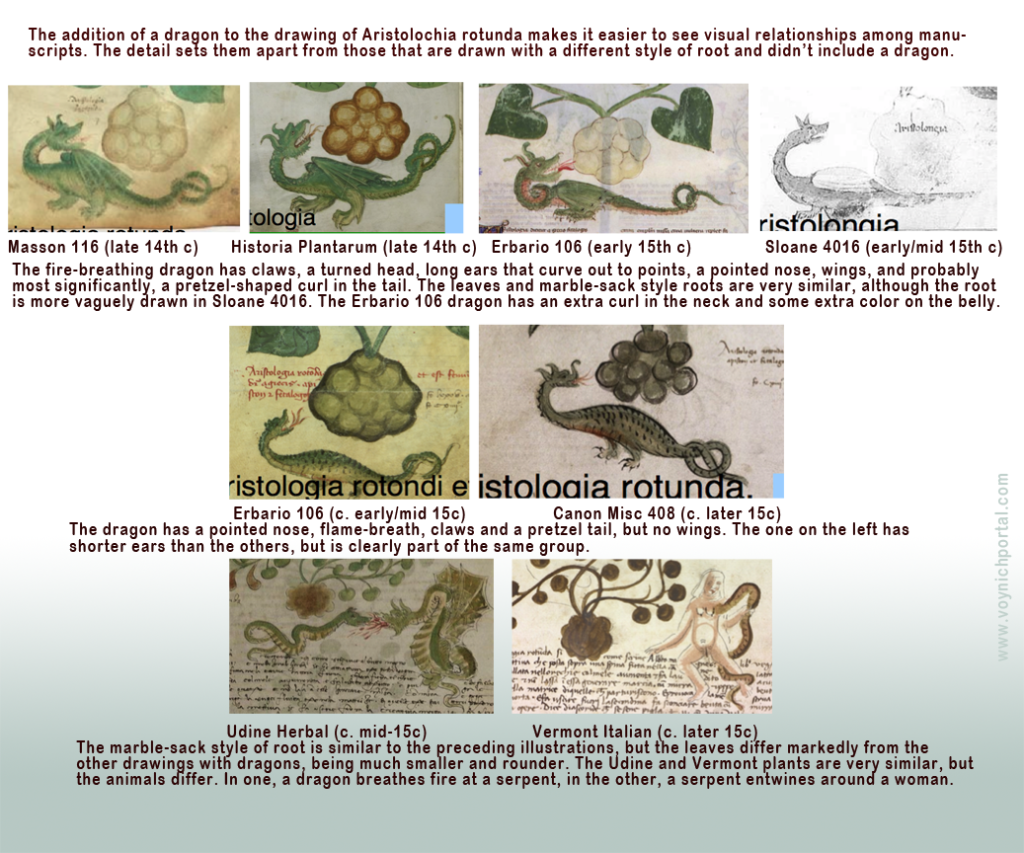

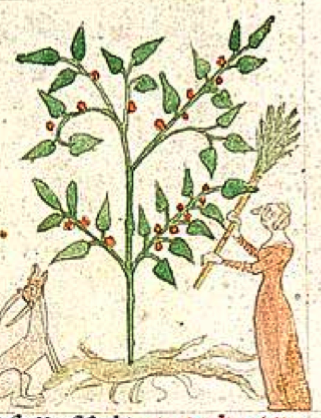

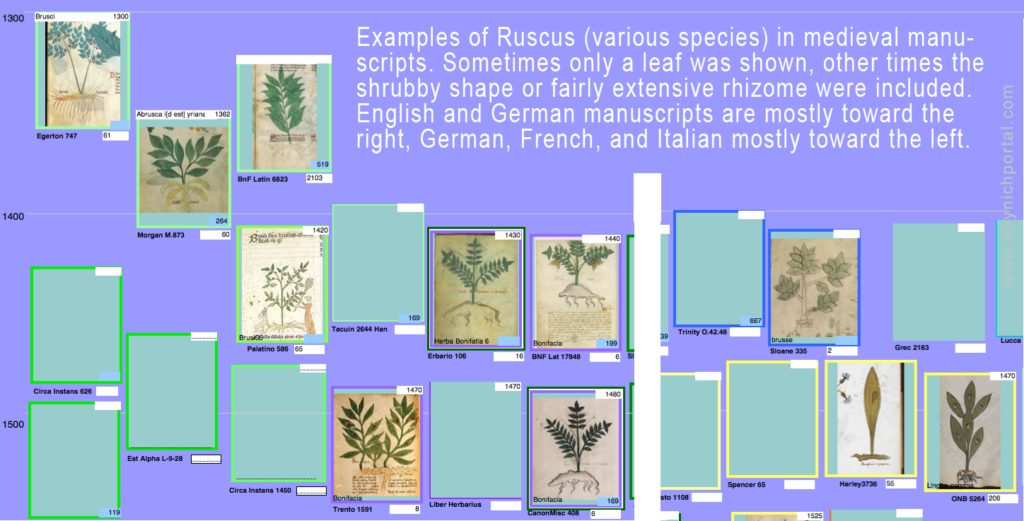

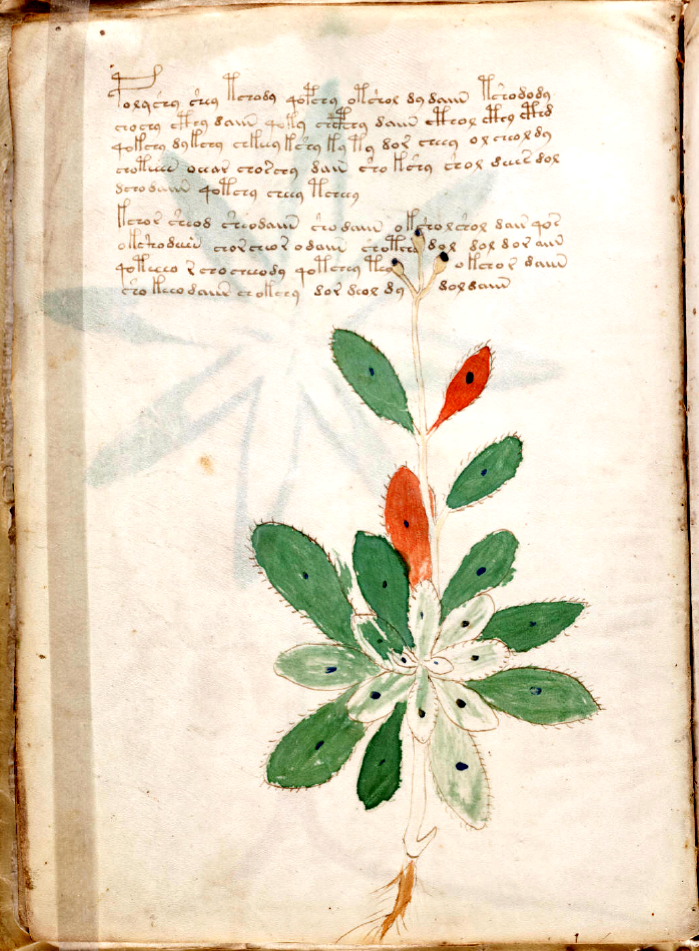

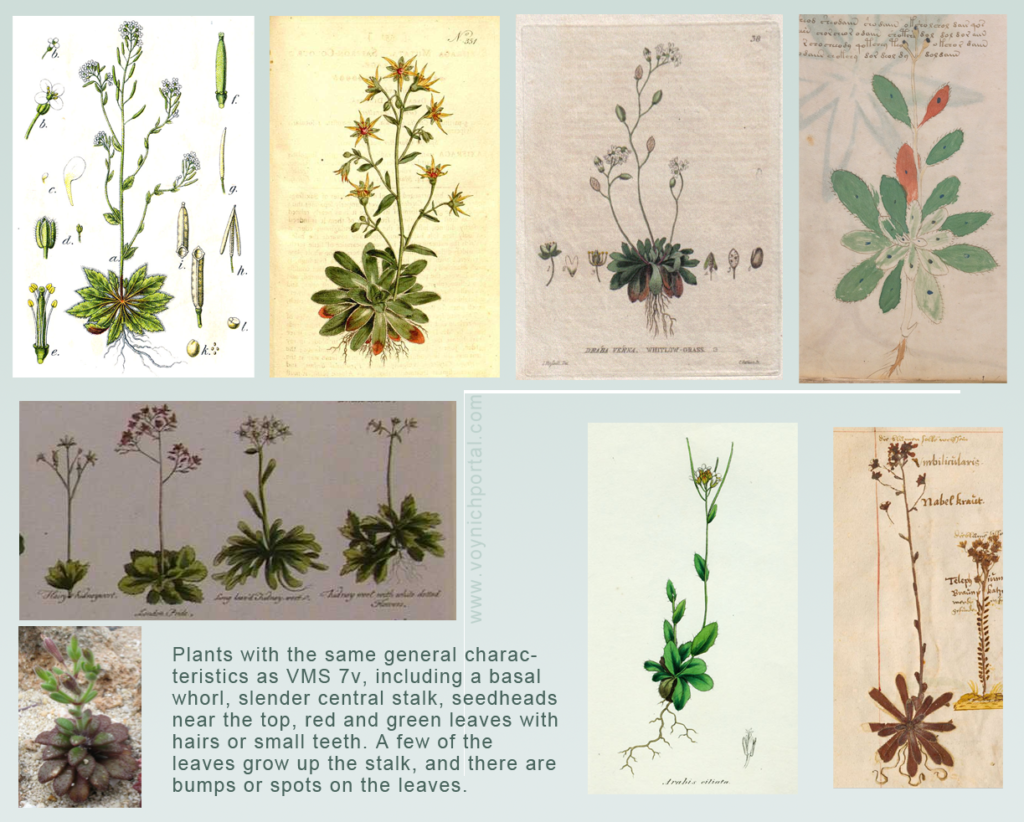

Many images get posted on the Voynich.ninja forum. Much of it is not new to me. I have more than a 300,000 plant images catalogued and accessible at the touch of a finger (I was interested in plants before I learned about the VMS). I also have more than 20,000 medieval plant images, many of which I can now recognize and identify on sight. I have related these to images of real plants so I can automatically display them side-by-side sorted by date and illustrative tradition. Here, for example, is a very small portion of the information I have for Agrimonia:

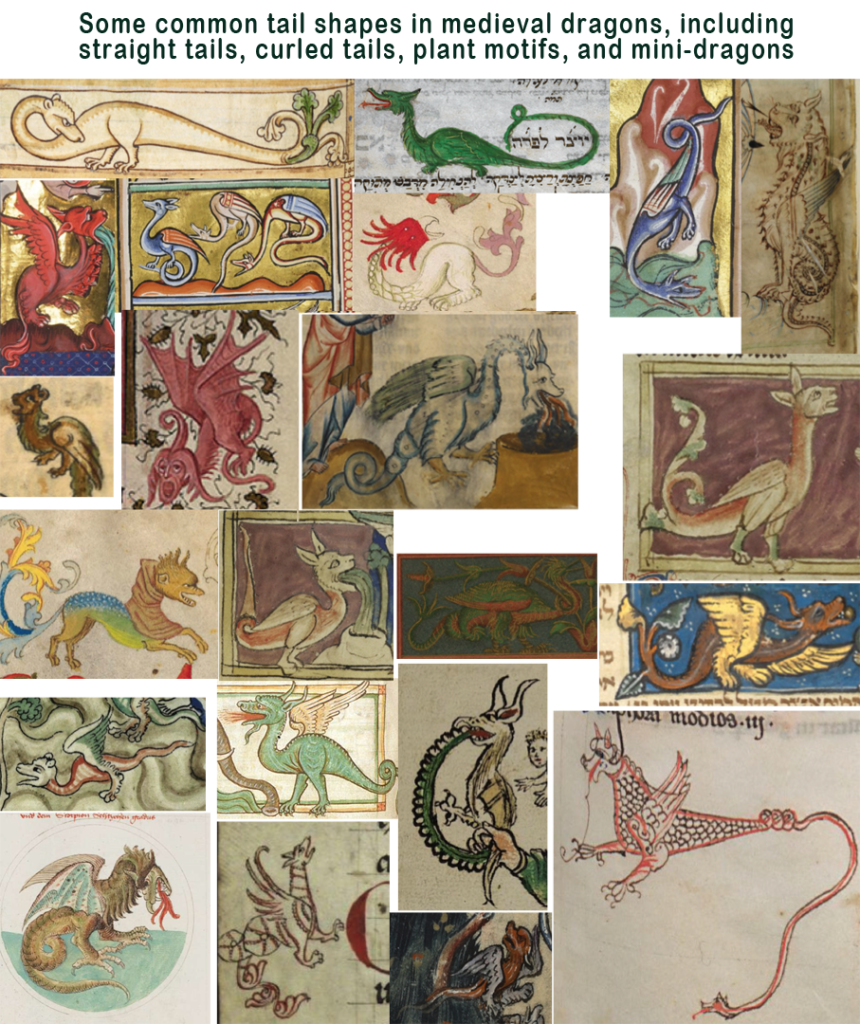

I have more than 550 complete zodiac series (almost 7,000 images) and thousands upon thousands of medieval and ancient animal images (dragons, sheep, bulls, snakes, fish, etc.), thousands of pictures of medieval maps, merlons, towers, castles, and escarpments. I’m not even going to try to count them but I had to buy another several-terabytes drive to accommodate the overflow.

Despite this penchant for collecting, I am fairly selective and realize now that I zoomed past a lot of Christian imagery because I didn’t think it was relevant.

The Sea Change

So what changed my mind?

It wasn’t any one thing, it was a pattern that was emerging…

For example, I took a good hard look at The Desert of Religion (Add ms 37049), the Carthusian manuscript described in a previous blog.

I mentioned Add ms 37049‘s humble drawing style (similar to the VMS) on the forum in February 2018, but I didn’t read it until a few months later. That’s when I realized the picture of Jerusalem had been extracted from the preceding mappa mundi rather than being included or repeated as a separate drawing. That is not common.

And that was an “Aha!” moment.

I thought to myself, “Is this the way the VMS is created? Have they taken things that usually go together and split them into separate chunks? Is this why the VMS is so hard to understand?”

Looking for Confirmation… Could it Be True?

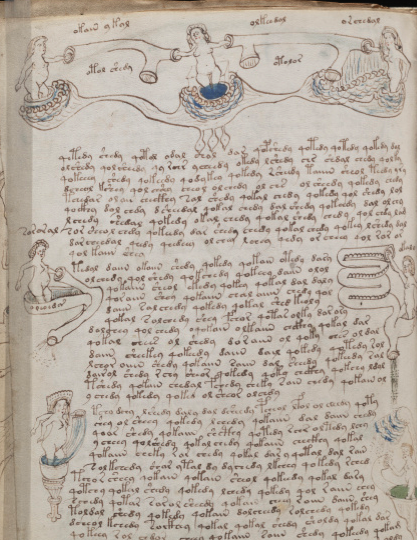

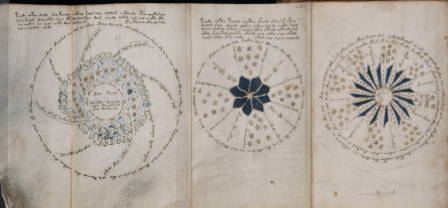

As soon as that thought crossed my mind I went to the cosmological section and looked for a Creation theme and this section (of which I enclose a portion) seems like a possible candidate. Many people try to identify this as individual stars or constellations, but I think it might be more metaphysical than physical:

But I wasn’t sure I could precisely pin it down without more study, so early in 2019, I tried another folio. I re-evaluated f86v and realized, after a few days, that the drawing wasn’t so strange after all….

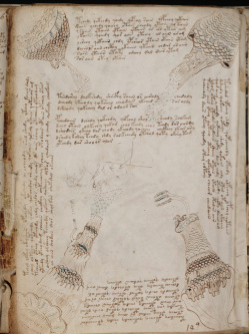

The VMS is drawn very differently from traditional manuscripts, but the themes of things falling out of the sky, birds, double tors (possibly representing the pillars of the sky), earthquakes, people hiding, and the world erupting into chaotic movement were common in biblical stories and apocalypse manuscripts, and I was able to find them in classical literature also, so I posted this blog in March 2019 with a sampling of possible interpretations, including one from the Book of Revelation.

I didn’t want to get locked into one idea, which is why I posted four ideas, but the one from Revelation matched quite well. That’s when I really started wondering if I had been wrong about the VMS. Maybe there was Christian imagery, after all. Maybe. (I was still reluctant to believe it.)

But whether I believed it or not, I have to admit, it changed the way I collected imagery from that point on, and it goosed me into trying harder to determine if the mystery critter might be a lamb rather than a pangolin or beaver.

The Best is Yet to Come…

So coming up to the present, things suddenly started happening fast.

K. Gheuens pointed out that helical twining could be found in medieval Arma Christi images (the same kind of twining as in the VMS Oak and Ivy plant).

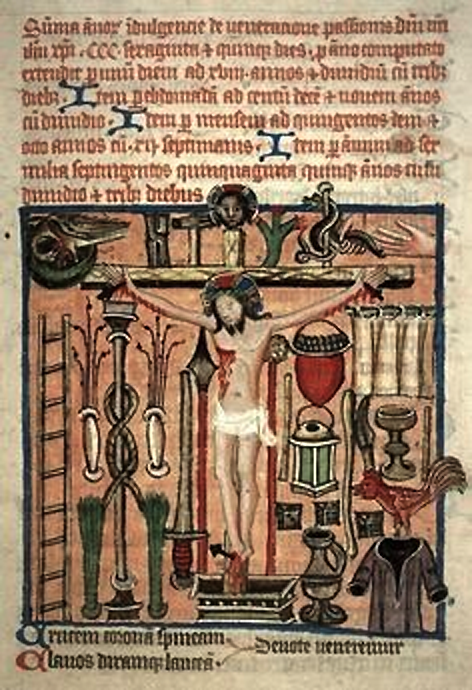

Here is an example of an Arma Christi illumination with helical twining on the pole that was used to bind Jesus:

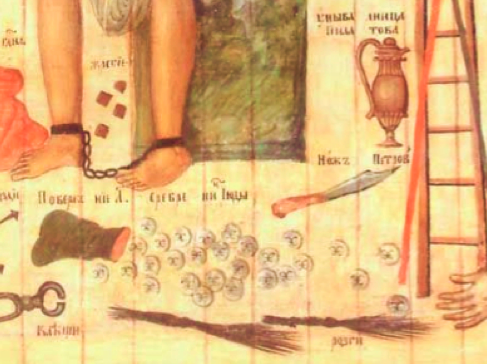

And this detail from a Russian Arma Christi illustrates that the number of coins doesn’t have to be 30 (there are 28 in this drawing):

I was thinking out loud on the forum when I wondered whether the major holy days might be encoded right into the VMS plants:

“Could a subset of the plants in the VMS (I’m thinking specifically the big plants and mostly the fanciful ones) represent a visual calendar? A way of expressing something about the most important holy days that was maybe tied in with what they believed about plants?”

And then, in the process of discussing this, and the mystery critter (is it the lamb of God?), mandorlas, sacred hearts, celestial flyers (“zoomers”), and poles in the Arma Christi in medieval manuscripts, K. Gheuens did some research on mandorlas and posted this blog, which I think is a must-read for every Voynich researcher.

https://herculeaf.wordpress.com/2019/08/04/blood-roots-and-lance-leaves/comment-page-1/#comment-2782

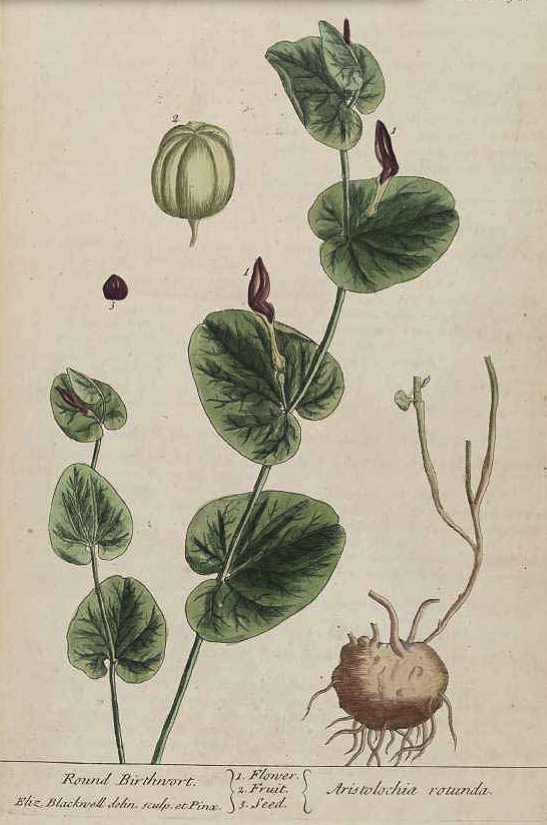

Because I had also been researching mandorlas, I knew almost instantly that Gheuen’s blog was going to be about the imagery on f17r (note the almond-shaped vagina-like red splotches in the root of the plant), but Gheuens went so far beyond, you could almost call it a bombshell in terms of our thinking about the VMS.

Read the blog and pay special attention to the analogies between some of the more stylized plants (ones that are hard to identify) and the various implements of the Arma Christi. This isn’t just about one plant drawing, it’s about a group of plant drawings. If he’s right, it will be the first time someone has convincingly discerned the meaning and inspiration behind a group of the less naturalistic plants.

As an aside, suns and moons with faces are generally associated with alchemical manuscripts from the later 15th and 16th centuries, and are rare in early medieval manuscripts, but they show up in Arma Christi images, as well.

We’re Not Finished Yet

Now we get to the part about interpretation. It’s one thing to say, hey, I found a picture of a tree-like thing and things twining around it in helical fashion (and this happens very frequently in Voynich research when images are posted without any follow-up to confirm or deny whether the idea has legs). It’s quite another to say, hey, here is a pattern of several illustrations that might have a cohesive explanation.

This is why I am taking Gheuen’s idea seriously. Because there might be a strong enough pattern to help us figure out if he’s right. Plus, the Arma Christi caught my attention because it has talismanic implications, as well, which might tie in with the strange writing in the VMS.

So, in that vein, I’d like to add a few more images that might relate to this in a way I never expected…

Back to the Future

Remember how I said at the beginning of this blog that I mostly gave up on the idea of Jerusalem being the object of the VMS map and moved on to other ideas? I couldn’t quite make it work—at least not as a strip-map or as traditional cartography. Maybe I need to look at it again, but in a slightly different way…

Maybe it’s not quite a map of Jerusalem, maybe it’s Jerusalem in the narrative sense. Take for example this picture, which no doubt has been mentioned in the VMS literature at some point for having a plant with twining, but what especially provoked me to drag it out of my files was the story behind it…

This painting illustrates the Betrayal of Christ (a theme related to the Passion of Christ which is, in turn, related to the Arma Christi) and includes Jerusalem, possibly Babylon (it was frequently included in mappae mundi in the Middle Ages), the Mount of Olives AND a tree with helical twining (the point is that they are all together in one painting):

The painting is part of an altar triptych that illustrates Christ being betrayed and arrested, and the mourning of the death of Christ.

“Maps” like this landscape of hills and castles don’t have to be geographically accurate. Their role is to tell a story. Could the VMS “map” (or parts of it) be a didactic version of one of these stories? Is that why it’s hard to pin down?

A Critical Look at the “Oak and Ivy”

It’s probable that the helical vines on the tree in the triptych painting above are metaphorically related to Arma Christi imagery, which would place the tree iconographically halfway between the Arma Christi “pole with ropes” version and the VMS Oak and Ivy—almost a visual bridge, so-to-speak.

But I now have second thoughts about the VMS tree. Maybe we should examine it again…

The following plant, from a Hebrew manuscript (lower-right), has a hauntingly similar twining pattern to the VMS Oak and Ivy. The main difference is that the VMS main stalk has branches going through rather than around (whether this is deliberate, creative, or a correction for a mistake is not clear). The leaves, however, are quite different, so it’s not a complete match:

Maybe the VMS Oak and Ivy is not meant to be two plants, as in herbal manuscripts such as Masson 116 or Sloane 4016. Maybe it’s one plant that has been pruned and twined in topiary style like the one on the right (note how the stalks are attached at the base, which sometimes happens with ivy (it insinuates itself into the bark) but which might mean it’s all one plant with three stalks).

I’ve seen plants where the stalks have been twisted and twined in remarkable patterns very similar to the above painting. Maybe the berries are not ivy berries, maybe they are olives, or something else related to a biblical story.

Now Everything Looks Different

I have to go back and look at everything again. I was almost certain the nymph middle-left on folio 77v represents the birth of Venus (or at least, that she is either Venus or a metaphor for birth), but maybe not.

And maybe the nymph at the top isn’t Cassiopeia after all (although I think Cassiopeia is a very good suggestion for the imperious seated nymph). Maybe the central position is the throne of the last judgment and the nymphs on either side are stand-ins for the angels Michael and Gabriel.

Things are shaking up right now, but maybe that’s a good thing. A new perspective. Let’s see where it leads

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2019 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved