In 2013, I posted some initial impressions of Plant 38r, stating that the “apostrophes” probably represented droplets (sap), but I couldn’t find enough public-domain images to fully explain what I feel it represents (posting an idea is one thing, convincing people that it’s a valid idea is entirely another) and opted to redact it rather than leaving it half illustrated. Since then, many more botanical images have been added to the Web and I finally have enough visual aids to demonstrate the logic behind this choice. — May 3, 2018

Description

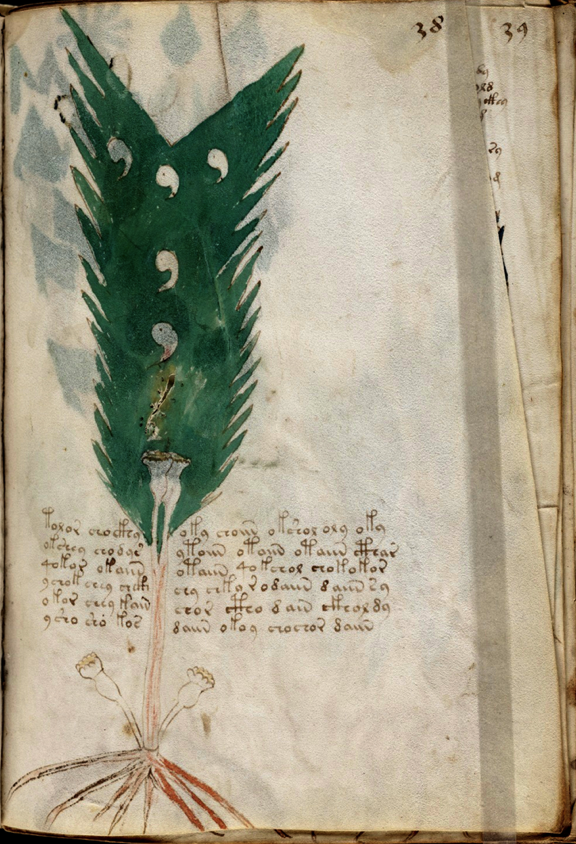

Plant 38r is a tall narrow drawing inhabiting the entire vertical space. Note how it has been slightly crowded toward the left of the folio. The sheet itself is narrower than others, with a long triangular section missing from the top right so that the text from folio 39r is visible.

Plant 38r is a tall narrow drawing inhabiting the entire vertical space. Note how it has been slightly crowded toward the left of the folio. The sheet itself is narrower than others, with a long triangular section missing from the top right so that the text from folio 39r is visible.

The drawing has a jagged green background against which are unpainted yin/yang-like symbols with a single carefully placed dot in each one.

There is a jagged line underneath them where the parchment has a hole that was at one time stitched and, below that, is a pair of vase-like shapes coming out of the stalk with a pale amber color painted inside, perhaps to give it a more rounded 3D look.

The vase shapes converge into a stalk that has been lightly brushed with reddish-brown and the bottom of the stalk sports two additional vase shapes splayed to each side. The base spreads into finger-like roots—brown on the left, reddish-brown on the right. A single paragraph of text fits around the plant where it narrows into the stalk.

When I first saw it, I wondered whether one could interpret the top green part as a river or stream. There are a number of herbal illustrations of water-cress, hepatica, and several aquatic weeds that are drawn within or along river-banks, but there are other aspects to this drawing that suggest the green area is probably representative of leaves rather than water.

I find it interesting that the average number of tokens per line on this folio has been reduced in much the same way as the width of the plant. Perhaps the scribe adjusted the text in anticipation of the sheet being trimmed to make it straighter?

Prior Identifications

I hadn’t seen any prior IDs at the time I worked out an explanation for this plant but it strikes me as metaphorical in some ways and literal in others and when I started exploring herbal manuscripts, I saw a pattern that might account for its features.

I think the height of Plant 38r, which touches the top of the folio and runs off the bottom edge, might be an indication of scale. The green area has a feather-, palm-, or fern-like quality, but if it’s meant to be a large plant, then some relationship to palm trees (or trees or large shrubs with fern-like leaves) seems more likely than allusions to feathers.

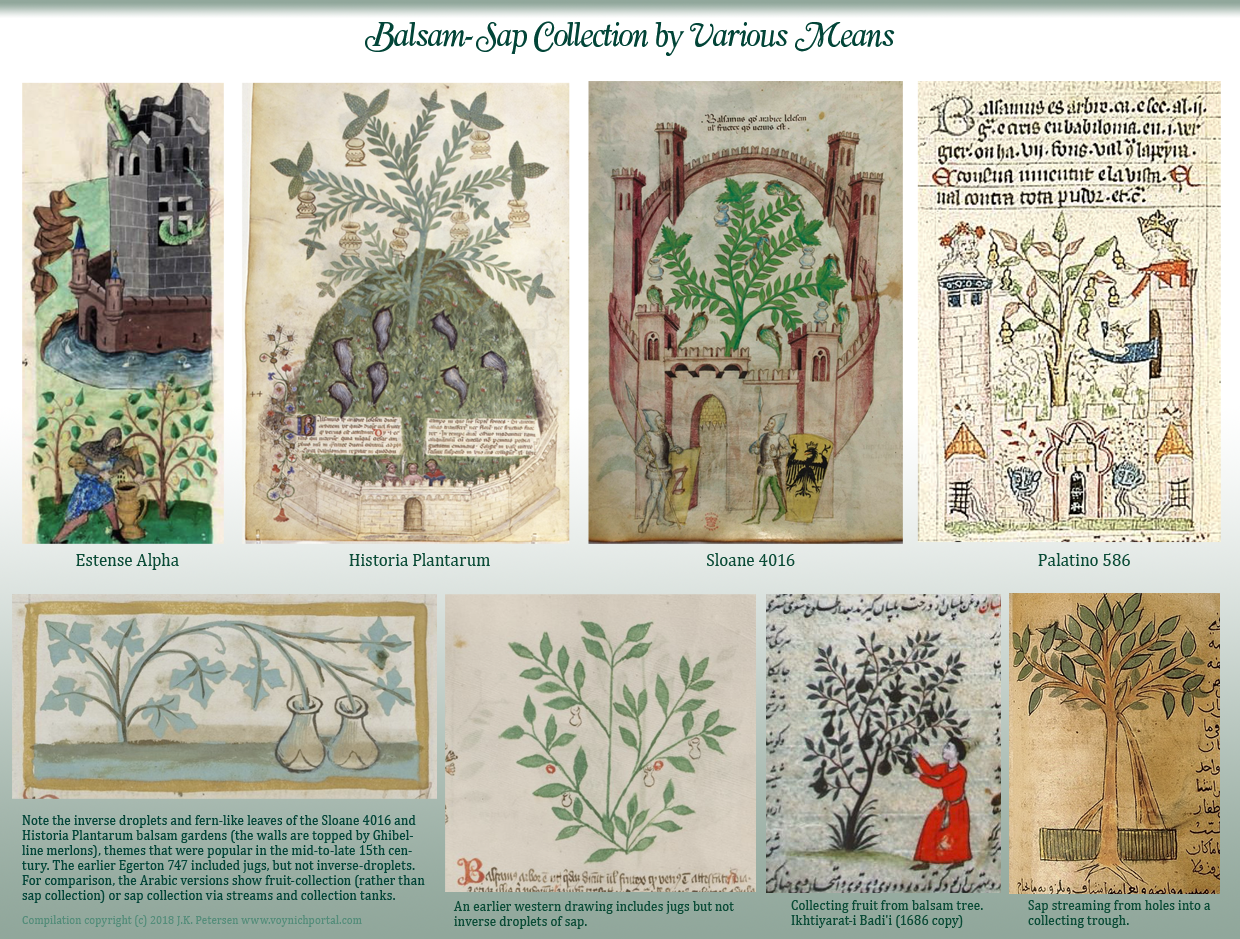

So, imagine for a moment that the green area represents leaves or a garden and the yin shapes are droplets, then the vase-like shapes beneath them might simultaneously represent flowers and receptacles for collecting sap. Sap was harvested from quite a number of plants, including date palms and the rare balsam tree, which is said to have been cultivated within guarded and gated gardens. The saps were variously used as sweeteners, perfumes, and medicinal resins.Thus, it’s not surprising that quite a number of herbal manuscripts include drawings of walled gardens and jugs for collecting sap, sometimes hung on branches, other times held in the hands of the workers [click to see larger].

Note how the droplets are drawn, with the tail facing down, the opposite of what one would expect if they were falling. The VMS drawing orients them tip-down, as well. Note also the fern-like way some of the leaves are drawn, even though balsam trees don’t immediately strike one as fernlike until one looks closely and simplifies their basic structure. The fern-like approach was more common in the 15th century. In the 14th century, the leaves were usually elliptical.

How Herbal Traditions Relate to the Voynich Plant

I am fascinated by the possibility that the VMS drawing depicts a plant that is harvested for sap, because there is still considerable debate over whether the VS plant images follow eastern or western traditions (personally I don’t think the dividing line is as cut-and-dry as some people suggest, since there was considerable copying in both directions, but there are some overall patterns). For example, the theme of vines twining around plants with oak-like leaves that I blogged about in 2013 is found in western manuscripts, but is it a solitary example (or a coincidence)? or are there several drawings in the VMS whose traditions can be identified?

I am fascinated by the possibility that the VMS drawing depicts a plant that is harvested for sap, because there is still considerable debate over whether the VS plant images follow eastern or western traditions (personally I don’t think the dividing line is as cut-and-dry as some people suggest, since there was considerable copying in both directions, but there are some overall patterns). For example, the theme of vines twining around plants with oak-like leaves that I blogged about in 2013 is found in western manuscripts, but is it a solitary example (or a coincidence)? or are there several drawings in the VMS whose traditions can be identified?

As far as I can tell, the inverse-droplet-and-jug theme is western, and wasn’t prevalent until the 15th century. You might notice that the Arabic manuscript included in the compilation above depicts sap collection in quite a different way, with liquid streaming from holes in the tree into a collection-trough at the base—no vases or droplets. The image to its left shows no sap collection at all, the “jugs” are actually fruits being harvested (probably Momordica “balsam apple” which is different from the resin-balsams). I am still keeping my eyes open for non-Western manuscripts with jugs and inverse-droplets but haven’t seen any yet.

As can be seen from the examples directly above, 14th-century images of balsam don’t typically include inverse-droplets (although sometimes they include vases or buckets), and tend to focus on naturalistic aspects of the plants. By the 17th century, accurate drawings of plants had largely superseded illustrations that incorporate the use and environment of the plant. So, the time period during which inverse-droplets were popular in herbal manuscripts is important to VMS research because it is temporally similar to the century during which crossbowmen appeared as Sagittarius in zodiac illustrations.

Why does the VMS drawing have dual-colored roots? I think it’s deliberate, not just haphazard paint application, but I’m hesitant to interpret it too soon. I’ll hazard a preliminary guess, however, that it might be because the Commiphora that produces Balm of Gilead and the Commiphoras that produce myrrh are quite similar, are harvested the same way, and are variously called “balsam” or, perhaps, that both balsam and date palm saps are represented.

Summary

Vase-like Commiphora bud [Photo detail courtesy of toptropicals.com]

If the VMS drawing represents balsam, or some kind of sap that is harvested like balsam, then it follows tradition in a number of important ways: it’s somewhat fern-like, includes a reference to collecting-vases, and includes droplets with their tails pointing down, all characteristics found in manuscripts of the early/mid-15th century. But it is also different in some significant ways. It is greatly simplified, includes no gates or castles, and yet has something lacking from the other medieval drawings… the unusual little flower “vases” characteristic of balsam trees, a detail that only someone interested in plants would notice because these buds quickly turn into little knobs. I’ve said many times that I think whoever drew the VMS plants wasn’t just a copyist, that it was someone who knew a few things about plants, and the addition of these buds seems to point in that direction.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright July 2013 and 3 May 2018 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved