28 May 2017

In previous blogs, I gave quick examples of the rule-dependent way in which Voynich Manuscript glyphs are combined (it’s far beyond the scope of a blog to define the entire rule-set, so I used a single page of text as an example and have been working on a long paper that describes the overall manuscript more fully). I also pointed out some of the more common atomic units, as I think of them.

Since that time I’ve been trying to think of a way to make these patterns and relationships easier to understand.

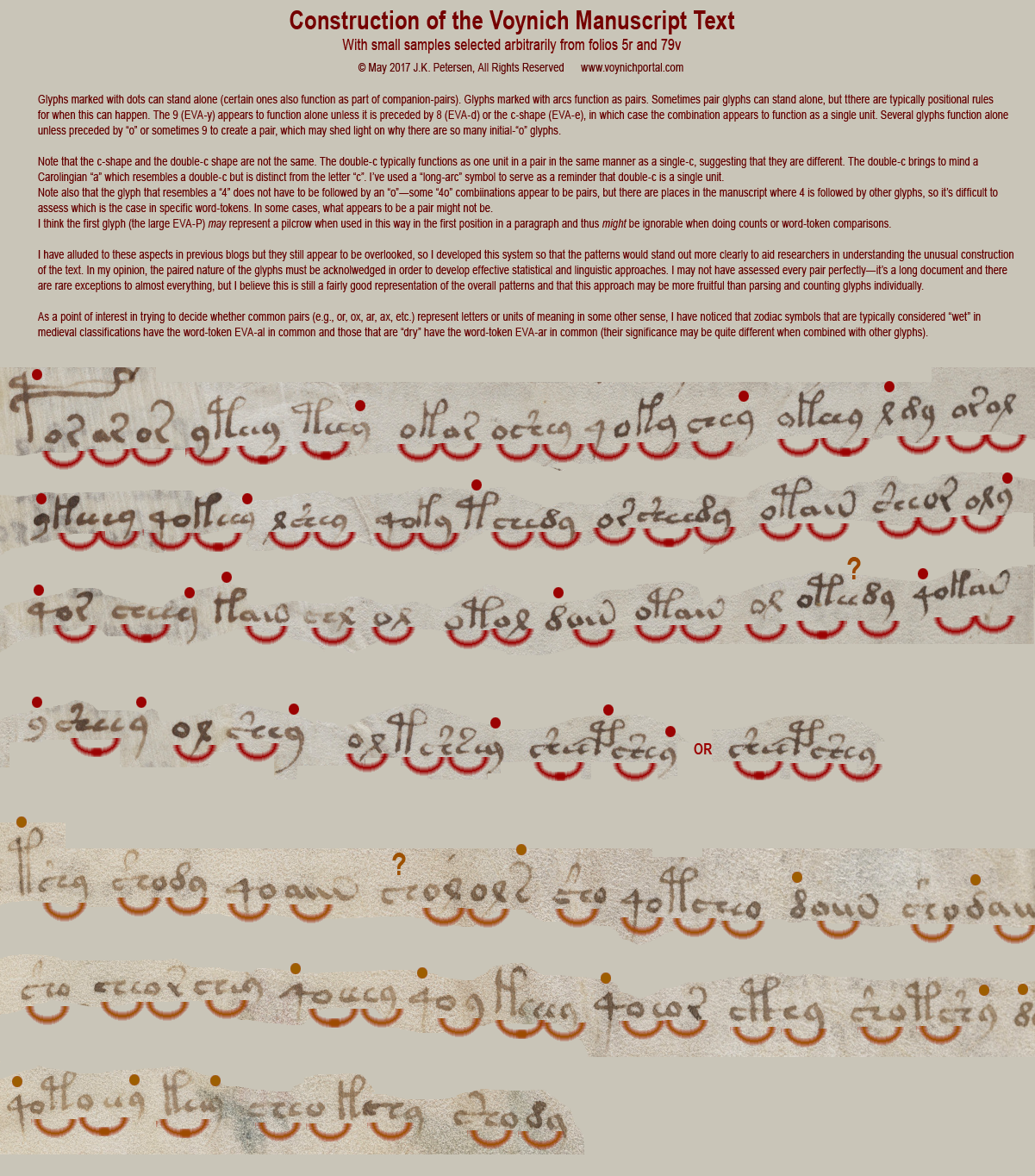

Hopefully this visualization method can illustrate why computational and linguistic attacks that assess individual glyphs may not yield fruitful results. The VMS has very particular ways of combining glyphs that affect not only which ones appear next to one another with greater frequency, and in what order, but also controls word-length in unique ways.

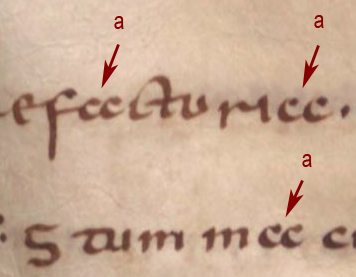

Note, as mentioned in the diagram below, a VMS double-c-shape (adjacent EVA-e glyphs) appears to function as a single unit in much the same way as a double-c shape in Carolingian script (right) represents the single letter “a”.

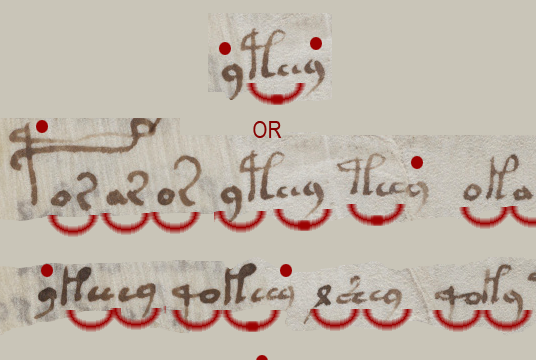

Note, as mentioned in the diagram below, a VMS double-c-shape (adjacent EVA-e glyphs) appears to function as a single unit in much the same way as a double-c shape in Carolingian script (right) represents the single letter “a”.- Certain glyphs, like EVA-d and EVA-s appear to function as single glyphs unless paired in very specific ways (with certain glyphs in certain positions, such as EVA-dy at the ends of words).

- Note the prevalence of combinations like EVA- or, ar, oI, 4o, ly, che, sho, and ey. These pair-syllables, in various combinations with glyphs that function as singles, characterize the entire manuscript, including text in labels and wheels.

- Note also the difficulty of assessing whether 4o is intended as separate glyphs or as a pair (in some tokens, it could be assigned either way and there are a few other combinations with this characteristic). I have included examples of both possible interpretations of 4o-tokens in the following illustration with the caveat that I am less sure of the 4o- breakdowns than most of the others.

Despite the difficulty of distinguishing singles from pairs with complete accuracy, I think these short examples come close and may help illustrate how the VMS text differs from common natural language patterns and patterns evident in medieval ciphered texts, and especially why one-to-one substitution systems have so far been unsuccessful.

Consequences

Also, give some thought as to how paired glyphs affect entropy and word length…

Paired glyphs greatly increase the number of letters or sounds a system could potentially represent. For example, if you had only o, a, r, and x, and placed them in a grid as pairs, your four glyphs could yield 16 pair-glyphs plus the four original glyphs to represent 20 letters or sounds. There aren’t as many combinations as this in the VMS, because glyph order is deliberately restricted and it’s not practical to put mirror pairs next to each other as they are hard to distinguish without extra spaces, but even so, the concept applies—entropy increases

As to word length… the VMS word-tokens are already short compared to natural languages, but if some of the glyphs are paired, word-length decreases further. If one is looking for letter or sound correspondence in text that has a large number of paired glyphs, then it’s more likely that they represent syllables, fragments, or abbreviations, rather than full words.

So, enough discussion… here are two examples that I grabbed arbitrarily. They’re short, but hopefully long enough to get the ideas across.

You can click on the image to see it full-sized (you may have to click again when the new tab opens to read the small print):

Postscript (after getting some much-needed sleep): I hope it is apparent from my previous comments that these are examples, not a definitive breakdown. In the illustration, I have broken down the “4o” words and some of the “9” words (EVA-y) in both ways to show both possibilities—with the 4 and 9 as singles and as pairs, because there is evidence elsewhere in the manuscript that both are possible interpretations. Some pairs (the common ones) are much more consistent and discernible than 4 and 9 word-tokens and I have a long list of stats for some of the more consistent pairs.

The distinction is important because pairs and singles may have different classes of meaning. For example, in Latin, the 9 character (which frequently functions as a single in the VMS, except when paired with EVA-d and possibly EVA-e) expands into prefixes like con- and com- and suffixes like -us and -um, which brings up the question of whether pairs might represent letters and singles might represent abbreviations, as were commonly used in medieval scripts, or (another possibility) whether they were intended to be differentiated in some other way, such as singles representing nulls, modifiers, or markers and pairs representing something else (letters, sounds, or concepts). Note that the singles are often at the beginnings of paragraphs and word-tokens, and also sometimes form one-glyph word-tokens. It is further possible that the high preponderance of “o” glyphs (particularly those in the first position) might be evidence of a pairing process intended to make tokens come out in a certain way (with a particular pattern or length).

All this assumes, of course, that the VMS text is meaningful, something that has not been proven. The pattern of pairs and singles could just as easily have been devised to make it easier to write meaningless text that looks like syllables and abbreviations. I still have a certain cautious optimism that there is meaning behind the text and will post another blog soon that explores some of the details of gallows characters that haven’t yet been discussed.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2017 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved