Monthly Archives: July 2013

Voynich Large Plants – Folio 93v

31 October 2020

This is one of the plant IDs I posted in 2013 and removed a few days later (I mention this as a courtesy to those who saw it in 2013 and wondered where it went). I am reposting it as it was originally, but I have updated a couple of images and added captions to the new images.

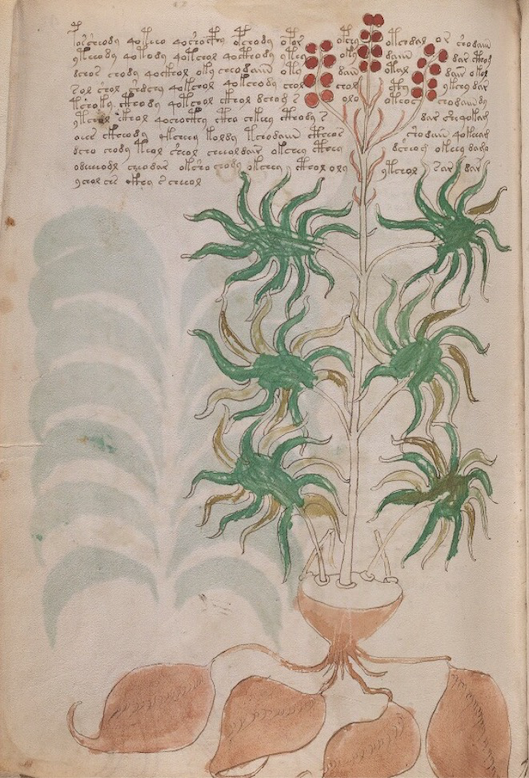

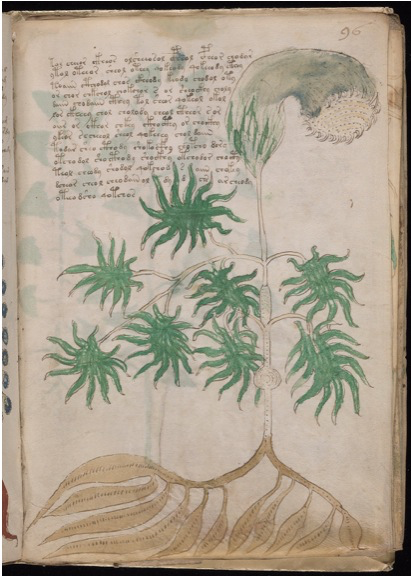

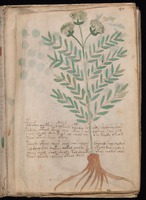

Plant 93v—The Plant with Yam-like Roots

Plant 93v almost fully inhabits the folio, from top to bottom and more than half of the width on the right side of the folio. It is bold, with emphasis on each of its major parts, seeds, leaves, and roots. The text covers the top third and wraps through the stalks of the plant.

The leaves are distinctive and almost insect-like, but there are many plants with digitate leaves, so the leaves are not necessarily symbolic. They may be somewhat stylized. Some of the extensions are painted a browner shade of green. They are arranged opposite on a tall central stalk. There are slender bracts near the top where the stalk branches into flower- and seedheads. The stalk is mostly unpainted except for the reddish-brown bracts near the top.

buy ivermectin scabies online Seeds

The rows of round red knobs might represent flowers, but I am inclined to interpret them as seeds, since they are similar to seeds on many plants and less similar to flowers. This arrangement of rows of flowers or seeds at the apex is common.

Prior IDs

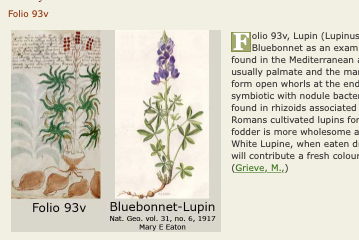

I don’t agree with many of Edith Sherwood’s plant IDs, but her ID for 93v is reasonable. I do, however, think there is a better ID, but let’s discuss hers first. Sherwood has identified f93v as Lupine.

Lupine has an upright stalk, and leaves that might inspire a stylized interpretation like the leaves in the VMS. The flowers are at the top of the stalk. The roots are knobby, but the knobs tend to be swollen parts of a tap root rather than separate yam-like extensions, and they are not especially large. They are more similar to the roots of dock (Rumex). Thus, Lupine matches fairly well on three counts, but the roots are not a great match.

Other IDs

There is another plant with an upright stalk, deeply serrated leaves and a row of seeds at the top that has roots very similar to Plant 93v. It is commonly found in medieval herbals. This is my first choice for the VMS ID…

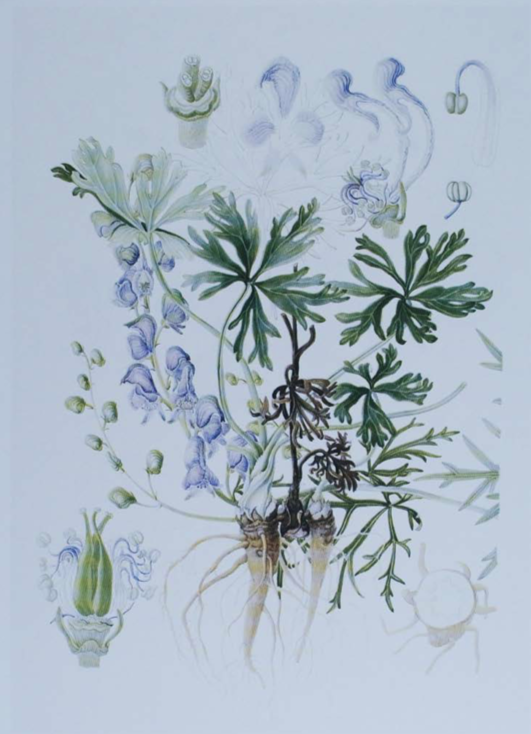

I think Plant 93v might be Aconitum, also known as monkshood. The roots are quite distinctive. They are yamlike, with long thin extensions at the end of the swollen part, and a small ‘bridge’ between each of the big knobs and the main stalk. This botanical drawing (left) illustrates the distinctive roots.

The various species of Aconitum that are common in Eurasia often have deeply serrated palmate leaves. The flowers are usually blue, burgundy, white, or whitish-yellow. Like lupine, the seeds are somewhat clawlike.

The multiple roots are sometimes like fat carrots, sometimes like yams.

Here is a species with more deeply serrated leaves:

In medieval herbals, monkshood was often called, Aconitum, Napellus, Mapellus, Napello, or Napelen. It is a toxic herb that was used in medicinal recipes.

Sometimes it was drawn with a single root (like a fat carrot), sometimes with multiple roots. Here are two examples, one from a 15th-century herbal, another from a later herbal from the Pemberton Collection that represent the roots in similar ways:

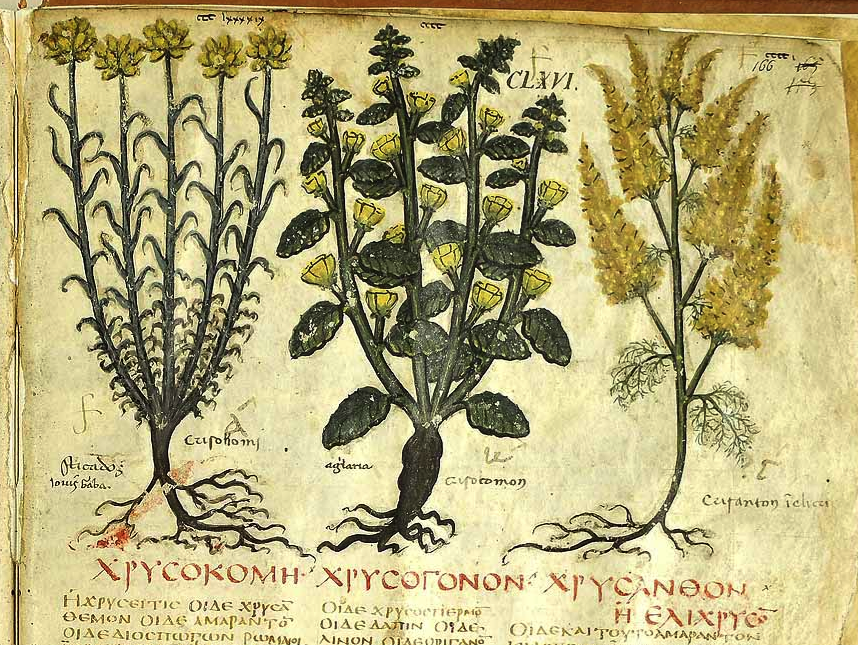

Both the above examples show two roots. What about multiple roots like the VMS? Those exist as well, as in this very early drawing from a Greek copy of Dioscorides:

Most of the VMS plants can be matched up with several plants, but the roots of plant 93v are distinctive and when combined with the leaves and seeds, only match a few.

Less Convincing IDs

In addition to Aconitum, I considered Delphinium, a Eurasian plant also called larkspur. It has palmate, deeply serrated leaves, a central stalk with flowers at the top, and roots that look like short small carrots which sometimes clump. It differs from the VMS drawing in that the roots do not have the distinctive narrow bridges that connect them.

Oxalis lasiandra has digitate leaves and knobby roots, but it lacks the bridge between roots and does not have the distinctively upright stalk.

Some forms of geranium have deeply serrated leaves, but the stalks tend to be less upright, and the rhizome is simpler and less swollen than the VMS drawing.

Lupine is, of course, a possibility but, as mentioned above, it does not have the yamlike bridged roots of Aconitum and the VMS plant.

Summary

My top ID for Plant 93v is Aconitum, but it should be mentioned that Plant 96r has similar characteristics. The leaves are digitate, the roots somewhat yamlike, numerous, and somewhat bridged. I don’t have a naturalistic explanation for the flower or seedhead, but perhaps it is mnemonic:

It’s hard to interpret the seed/flowerhead, but there are several species of monkshood, and medieval herbals sometimes included more than one.

Is it possible this represents another species of Aconitum and the somewhat stylized thickened drooping head represents a monk’s hood as a mnemonic for the plant name? If so, then the VMS follows a tradition of including more than one species of Aconitum, possible evidence connecting it to herbal customs of the time.

If it’s not another species of Aconitum, perhaps it is something like Arum vulgaris, voodoo lily, the form with long narrow leaves and swollen stems:

I am not certain if 93v and 96r are connected in terms of species, but they have several traits in common, so they might belong in the same plant family.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright July 2013 and October 2020, J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

Voynich Large Plants – Folio 93r

In 2007, when I first encountered the VMS, I paged through the plants, over and over, to see if they were drawn according to a personal formula. What did the illustrator consider important? How accurate were they? How were certain features expressed? Could the colors be trusted? Was Plant 93r a sunflower?

After almost a year of study, I had a better sense of how the illustrator approached certain details and had learned to respect the drawings. In my opinion, the naturalistic drawings (there are quite a few of them, mixed in with some that are more stylized), are reasonably accurate, even if the drawing skills are modest.

I noticed that the leaf margins, and the general shape and arrangement of the leaves, is quite good, making allowances for mnemonic exaggeration. The colors of the leaves also seemed to be reasonably good. The only part that seemed consistently questionable was the color of the flowers, at least it seemed that way until I realized some of the drawings might have been drawn from dried plants (e.g., blue flowers often turn to brown or yellow as they dry) and some appear to have gone to seed. I suspect that blue might be used symbolically to represent seeds (I’m not completely sure, and even if it’s true, it might not be true for all of them).

That’s when I began trying to identify the plants, including the one on folio 93r.

To this day I am not entirely sure how naturalistic the roots are intended to be. Just as some plants have leaves that appear to be mnemonic, some of the roots seem to be also (although it’s possible to be both somewhat naturalistic and mnemonic at the same time). I decided to trust the shape of the roots as naturalistic if there were no obvious animal, cultural, or anatomical imagery incorporated into them.

The Identity of Plant 93r

In 2013, when I originally planned to post this blog, there were very few public domain illustrations I could use to convincingly illustrate alternate plant IDs. That situation has changed, so it’s time to get it finished.

In 2013, when I originally planned to post this blog, there were very few public domain illustrations I could use to convincingly illustrate alternate plant IDs. That situation has changed, so it’s time to get it finished.

Edith Sherwood stated up-front that she considered the Voynich Manuscript, “…a 15th century Italian manuscript” and that she and Erica’s plant IDs were limited to “plants native to Europe or at least the old world and excluded all plants from the Americas”. In other words, the sunflower, a plant that was introduced to the Old World in the early 16th century, was explicitly excluded by the Sherwoods as a possible ID for this plant. But that didn’t stop others from proposing it.

I didn’t really care whether it was an Old World or New World plant. Evidence would eventually settle that question, and it made no difference to me how many others had apparently insisted it was a sunflower, I simply researched as much as I could about the history and distribution of sunflowers and sunflower-like plants. The reason I was unwilling to commit to sunflower is because certain species of Chrysanthemum, daisy, or Helichrysum resemble sunflowers if imperfectly drawn or examined at a different scale.

I don’t think anyone can say for certain that this is sunflower, including botanists who seem adamant on the point. The fringe surrounding the seedhead is very fine compared to the triangular bracts that ring most sunflowers, and sunflowers with large seedheads often have tuberous roots that are lumpy, like ginger, not tendril-like, as in the VMS drawing. The leaves aren’t typical for sunflowers either, although there are some species with longer, more lanceolate leaves, but they tend to be the ones with longer petals in relation to the seedhead.

Leaves and Stalk

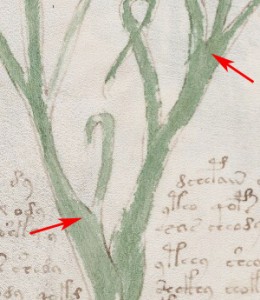

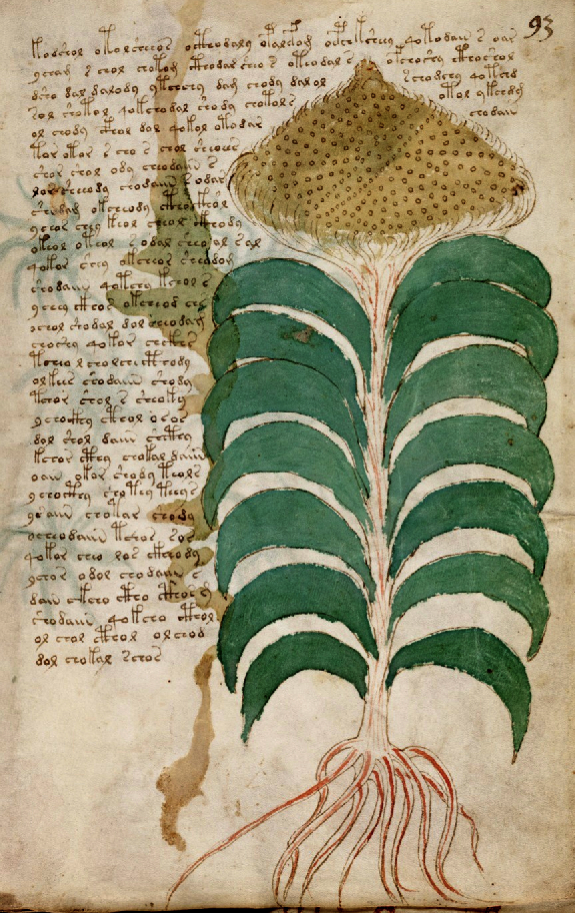

Find a high-res scan and look very closely at how the VMS leaf attachments and stalk are drawn. I’ve never seen anyone comment on this. Occasionally they mention the shape of the leaves, but not how carefully the illustrator has laid the short petioles against the stalk so that they appear almost to overlap. If you were to “flatten” this plant the way the VMS plant has been flattened (note that all the leaves go to the sides—it’s not a 3D arrangement), the VMS illustrator may have been trying to draw the kind of leaf arrangement illustrated on the right. This is not easy for someone with limited drawing skills:

Note also how the botanical drawing on the right shows lighter undersides on the leaves, a trait that is more apparent near the stem. There are some light touches of brick-red on the lower stems. This is because stems like this are often more “woody” and darker near the base (this is seen on many species of plants).

Note also how the botanical drawing on the right shows lighter undersides on the leaves, a trait that is more apparent near the stem. There are some light touches of brick-red on the lower stems. This is because stems like this are often more “woody” and darker near the base (this is seen on many species of plants).

The leaves of Helichrysum, like the flowers, can be quite variable, but some species have slimmer, longer leaves than sunflowers. Note how the one on the left is close to the stem and almost overlapping and quite similar to the way the VMS leaves are drawn near the stem. The second illustrator (middle) chose to draw the leaves splayed out, with a reddish stem. The VMS drawing seems to fall somewhere in between:

Bracts, Petals, and Seeds

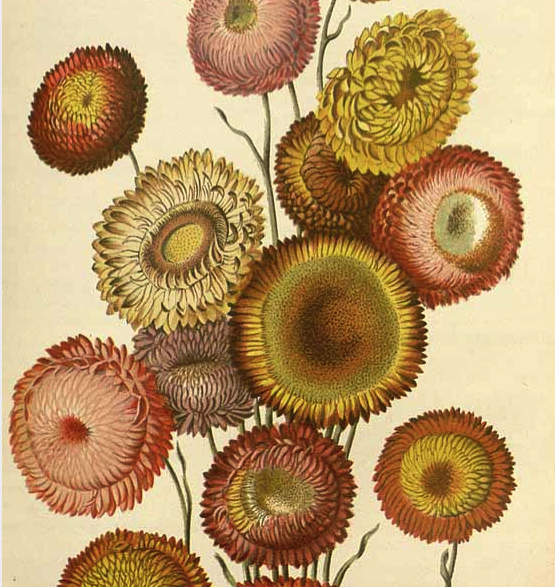

The shape of the sunflower seedhead may seem unique, but it’s only the large scale that creates this illusion. In fact, this form of seedhead is widely seen in the aster family.

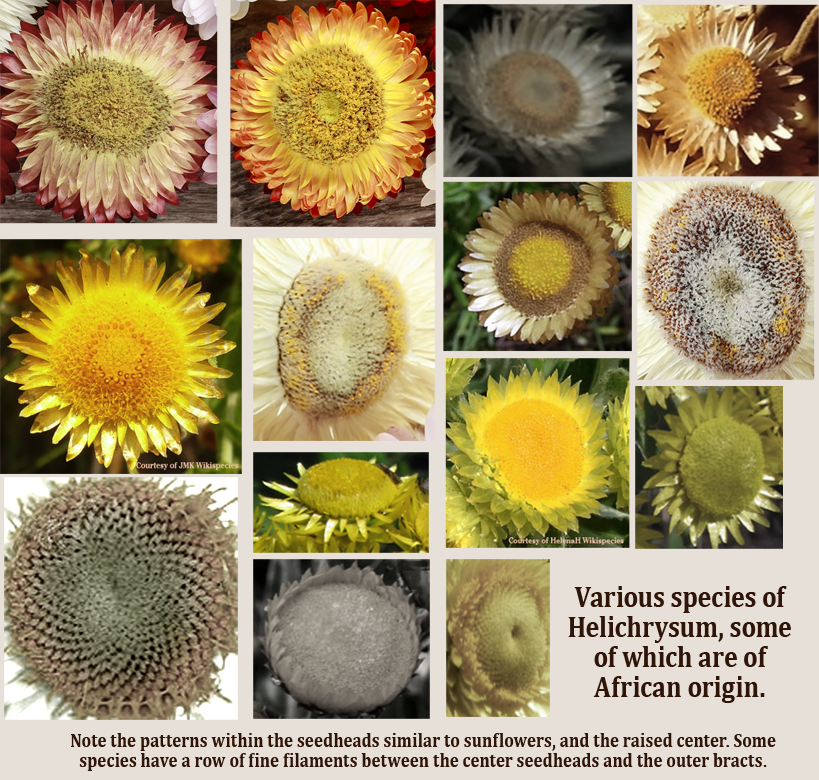

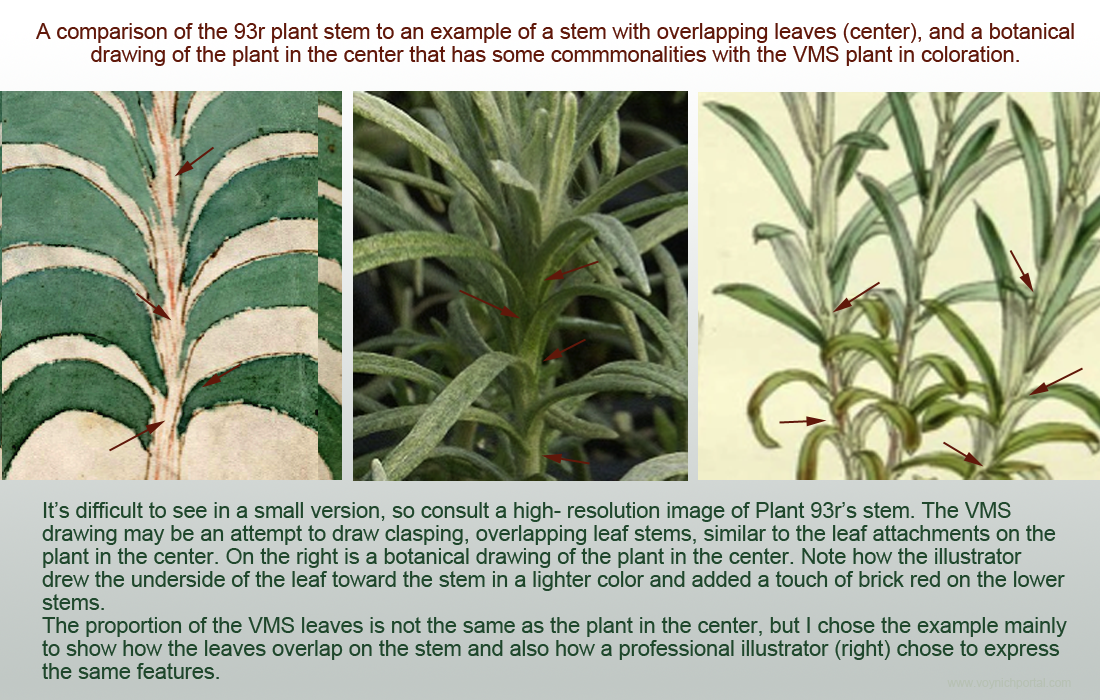

These examples demonstrate that Helichrysum (as one option) would look significantly similar to Helianthus (sunflower) if drawn by an illustrator with limited skills:

Here are botanical drawings of two different species of Helichrysum, one with long stalks, another with shorter branching stalks (sunflowers also come with both kinds of stalks):

Helichrysum grows worldwide, but several species are native to Africa. Some of them are from the Cape region and would not have been known in central Europe in the early 15th century, but others are from coastal Africa and the Mediterranean and might have been imported to Europe as a medicinal plant. Even today, Helichrysum is sold as an essential oil.

If you’re wondering if Helichrysum and other asters were known in the Middle Ages, the answer is yes. Chrysokomi, Chrysogonon and Chrysanthon were documented in early copies of Dioscorides, and some of the late medieval botanical drawings refer to some species of Helichrysum as Gnaphalium (the sunflower is also in the Compositae (aster) family):

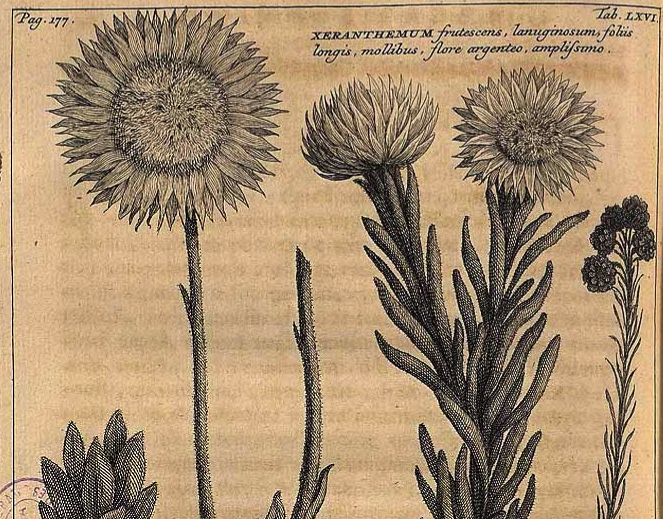

You might also recognize the name “Xeranthemum” as similar to Chrysanthemum (many sunflower-like plants, including the sunflower itself, were sometimes referred to as Chrysanthemums in early published botanicals). This “Xeranthemum” is an African cousin to the Carlina thistle (Carlina is mentioned in numerous medieval herbals):

You might also recognize the name “Xeranthemum” as similar to Chrysanthemum (many sunflower-like plants, including the sunflower itself, were sometimes referred to as Chrysanthemums in early published botanicals). This “Xeranthemum” is an African cousin to the Carlina thistle (Carlina is mentioned in numerous medieval herbals):

Summary

There are other possible IDs for Plant 93r and unfortunately I don’t have time to post all my data or hunt for suitable pictures, but the point I wanted to make is that the VMS drawing does not have to be a sunflower. I’m not completely ruling it out, but the bracts seem rather small and narrowly spaced for Helianthus, and the leaves too narrow for the species of sunflowers that have larger seedheads, so the ID can certainly be challenged.

It could be Helichrysum, or perhaps one of the other asters with prominent seedheads in proportion to their overall size (the gerbera daisies come to mind), but it makes no sense to insist that it is sunflower as long as there are other plants that resemble the VMS plant as well or better.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2 October 2018 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

Large Plants – Folio 90v

Voynich Large Plants – Folio 90r

Description

Plant 90r fills most of the page from top to bottom—in fact, it barely fits on the page and one wonders if the parchment at the top has been trimmed.

Plant 90r fills most of the page from top to bottom—in fact, it barely fits on the page and one wonders if the parchment at the top has been trimmed.

The leaves are medium green and painted with a light touch, with some a little lighter green than others and a few with a slightly yellow-green tint. Note how the paint has been applied more carefully than in may of the VMS illustrations. The painting of the roots is less sloppy also.

The leaves are lanceolate, opposite, and odd pinnate. The stem is slender and upright and divides into three at the top, with fluffy flower heads cupped in dark green calyces.

The roots are slightly curved, medium brown, relatively uniform (as roots go)—the kind of roots that are found on many buttercup plants (in other words, no lumps, not distinctly a tap root, and without a distinctive rhizome) except that the top of the root is thick, like a thumb.

There is a sprinkling of small black spots on this page that look like worm holes.

There are two blocks of text near the base that divide across the stem of the plant.

Prior Identifications

Edith Sherwood has identified this plant as fleabane (Conyza bonariensis), probably based on fleabane’s fluffy seedheads, but the resemblance is only superficial. The VM drawing might be seedheads, but it might also be the flowering phase of the plant and, if so, it doesn’t match as well because C. bonariensis has a fairly tight small flower like a groundsel—it’s shaped a bit like a microphone rather than being broadly open. Even if the VM plant is in the seed stage, it still doesn’t match C. bonariensis very well because fleabane fluffs out into a ball with the calyx hidden within the fluff, like a dandelion.

Edith Sherwood has identified this plant as fleabane (Conyza bonariensis), probably based on fleabane’s fluffy seedheads, but the resemblance is only superficial. The VM drawing might be seedheads, but it might also be the flowering phase of the plant and, if so, it doesn’t match as well because C. bonariensis has a fairly tight small flower like a groundsel—it’s shaped a bit like a microphone rather than being broadly open. Even if the VM plant is in the seed stage, it still doesn’t match C. bonariensis very well because fleabane fluffs out into a ball with the calyx hidden within the fluff, like a dandelion.

C. bonariensis does match Plant 90r in that it has narrow lanceolate leaves, but that’s where the resemblance ends. Unlike C. bonariensis, the leaves of 90r are not branched and they are not opposite. They are not odd pinnate either. Furthermore, the roots are not a good match. C. bonariensis has a fairly beefy tap root that doesn’t branch significantly until a few inches below the ground. Plant 90r has kind of a thick nub that splits into fingers rather than a tap root.

There are a number of plants that more closely resemble the VM plant than C. bonariensis.

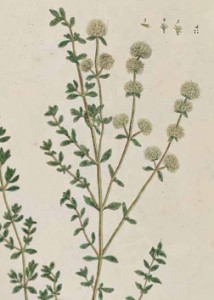

Other Possibilities

You could argue that Plant 90r is Spanish thyme (Thymus mastichina), a culinary and medicinal plant that grows in Portugal and Iberia. Like Plant 90r, it has fluffy greenish-white heads, branching stems, and opposite leaves. The problem with T. mastichina is that it doesn’t branch as evenly as Plant 90r. The fluffy heads do sometimes split into three (though not as evenly as 90r) but more often they are tiered. The top end of the root isn’t as thick as the VM plant either.

You could argue that Plant 90r is Spanish thyme (Thymus mastichina), a culinary and medicinal plant that grows in Portugal and Iberia. Like Plant 90r, it has fluffy greenish-white heads, branching stems, and opposite leaves. The problem with T. mastichina is that it doesn’t branch as evenly as Plant 90r. The fluffy heads do sometimes split into three (though not as evenly as 90r) but more often they are tiered. The top end of the root isn’t as thick as the VM plant either.

There is a tall spindly plant called Cephalaria uralensis that grows in eastern Europeand Russia. It is related to teasel and has odd-pinnate lanceolate leaves that branch opposite each other, directly from the stem, as they do in the VM plant. It has round, fluffy, creamy-white flowers with long stamens. It might be a good candidate for Plant 90r except that the flower stems are distinctively long (very long) and it has a fairly thick tap root.

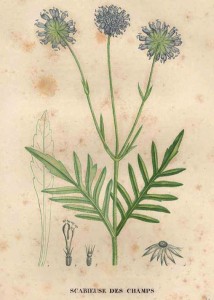

Another cousin of the teasel is Scabiosa canescens, a charming flower with leaves that branch almost exactly like Plant 90r, and a fluffy flower head that turns into an almost spherical seed capsule with protruding sepals. There is usually only one flower at the end of the stem, but sometimes it branches into three lower down on the plant (with long stems like Cephalaria uralensis). A flower that grows in fields in France, Scabiosa arvensis, is similar. Both of these, however, have tap roots.

Another cousin of the teasel is Scabiosa canescens, a charming flower with leaves that branch almost exactly like Plant 90r, and a fluffy flower head that turns into an almost spherical seed capsule with protruding sepals. There is usually only one flower at the end of the stem, but sometimes it branches into three lower down on the plant (with long stems like Cephalaria uralensis). A flower that grows in fields in France, Scabiosa arvensis, is similar. Both of these, however, have tap roots.

Is it possible to find a plant that matches the flowers/seedhead, leaves and the root?

An Old Medicinal Herb

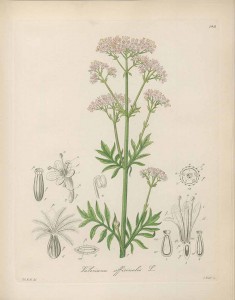

There is a plant that comes very close to Plant 90r in significant ways. It has lanceolate odd-pinnate leaves growing opposite along the stem, stems that split near the top, often into three or more flower heads. Some species have a root with a thumblike knob near the top before it splits into finer roots.

There is a plant that comes very close to Plant 90r in significant ways. It has lanceolate odd-pinnate leaves growing opposite along the stem, stems that split near the top, often into three or more flower heads. Some species have a root with a thumblike knob near the top before it splits into finer roots.

Valeriana is a fairly variable species, but several have odd-pinnate leaves that are a good match for Plant 90r, possibly Valeriana phu, V. sylvatica, or V. dioica. It’s notable that the herbal tradition for depicting this plant in medieval times is to show it splitting into three flower heads even though in nature, it often has more.

Valerian has a very long history as a medicinal plant and is still a staple in many medicine cabinets. It also has some toxic properties and must be processed and used with care.

Valerian has a very long history as a medicinal plant and is still a staple in many medicine cabinets. It also has some toxic properties and must be processed and used with care.

It would be hard to say whether Plant 90r resembles Valeriana or Scabiosa more closely. The main difference is the root. Scabiosa has a distinct tap root whereas Valerian sometimes has a tap root that is knobby near the stem but then branches more broadly. Depending on how literally one takes the VM drawing, one might lean toward Valeriana. Also, given Valerian’s significant history as a medicinal herb, it would not be surprising to find it in a health-related compendium.

Plant 90r may not be Valeriana (or Scabiosa), but it’s more likely to be either of these than Conyza bonariensis.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2013 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

————————————————————————————————-

Addendum: I found another picture in my files that illustrates why I’m leaning toward Valerian phu as an ID for Plant 90r. It’s drawn by Elizabeth Blackwell, known for her accuracy in portraying herbs.

Note the fine-textured odd-pinnate leaves that branch to either side (Scabiosa also has this), the three-branched heads of white blossoms, and the three green protrusions cupping each flower head. The root is moderately thick with many root hairs. It matches well with the VMS drawing.

Large Plants – Folio 89v

Large Plants – Folio 87v

Large Plants – Folio 87r

Large Plants – Folio 66v

Large Plants – Folio 65v

Folio 65v shows a large plant illustration stretching from the bottom edge almost to the top and sides. Text is sparse on this page, comprising less than six full lines, and is broken across the stem of the plant (assuming it’s intended to be read line by line).

Most of the plant is painted green with the exception of the inner flower at the top, which is blue. The smaller flower heads (or seed heads) surrounding it have small petals or other structures, that have been left unpainted. The roots are medium brown.

This page follows another Large Plant page and immediately precedes a page full of text with columns of characters down the left side.

Details

Stems: The stems branch regularly, sometimes opposite, sometimes alternate, becoming thinner near the seed heads (I’m calling them “seed heads” to distinguish them from the larger central head that more nearly resembles a flower head).

Leaves: The leaves are long, narrow, sparse, and some curl back toward the ground.

Flower: The top central structure looks like a flower that is partially emerged or perhaps which doesn’t protrude very far even when in full bloom. It is drawn in green and blue. The green area has spikes that may represent a calyx.

Seed Heads: It’s not certain these are seed heads, but many plants with blossoms will have a rounder look to the head and missing or shriveled petals when they go to seed. The centers have been painted green and the small rounded “petals” or other structures remain unpainted.

Side note about the painting technique: Throughout most of VM 408, it appears that the writer and illustrator (we don’t know for certain they are one and the same, but I suspect they are) preferred to write or paint as much as possible before redipping the pen or brush. Thus, the first few dabs are dark and those following become progressively lighter. Here the seed heads top left are darker green, and the rest become lighter as the pigment is depleted. If the illustrator were right-handed and were concerned about not smearing, then starting top left would be practical. It looks like the brush may have been dipped two or three times to fill in all the seed heads.Roots: The roots are fairly numerous and fairly thick, like multiple tap roots, with fine hairs emanating along their length. They are painted medium brown.

Prior Identification

Edith Sherwood has identified this as Centaurea cyanus (cornflower), perhaps because the part that appears to be the flower is painted blue.

Edith Sherwood has identified this as Centaurea cyanus (cornflower), perhaps because the part that appears to be the flower is painted blue.

Other than the color, however, Plant 65v differs from C. cyanus in a number of ways:

- C. cyanus has a rounded, scaly base to the flower head. Plant 65v is more tapered and triangular and lacks the scales.

- C. cyanus spreads out in an umbrella-like fashion from the flower head and each individual petal splits into several pointed tips. Plant 65v barely protrudes and does not have the characteristic parasol shape of the cornflower.

- C. cyanus has more numerous leaves and they do not typically curl like the leaves of 65v. Nearer the base, C. cyanus leaves are larger and have a basal whorl somewhat like a dandelion.

- C. cyanus typically has a single taproot rather than multiple taproots.

- It appears that other plants may be a better match than Centaurea cyanus.

Other Possibilities

The blue flower and long slender leaves of 65v bring to mind Cichorium intybus (chicory), a salad and forage plant, but chickory leaves are somewhat serrated and they don’t curl in the manner of Plant 65v. C. intybus doesn’t have the scaly round flower head found on C. cyanus, but it does have petals that fan out like a reverse parasol. I don’t think it’s a likely a match for Plant 65v.

The blue flower and long slender leaves of 65v bring to mind Cichorium intybus (chicory), a salad and forage plant, but chickory leaves are somewhat serrated and they don’t curl in the manner of Plant 65v. C. intybus doesn’t have the scaly round flower head found on C. cyanus, but it does have petals that fan out like a reverse parasol. I don’t think it’s a likely a match for Plant 65v.

Scorzonera purpurea or many of the other Scorzoneras might be considered. Many Scorzonera have long narrow leaves that sometimes curl, long calyxes, and one or more tap roots that are sometimes eaten as food. Some Scorzonera have scaly calyxes similar to Centaurea but others (e.g., S. purpurea) have a simple double-layered calyx rather than a complex of scales.

Scorzonera might be a better match than Centaurea, but there are others that come closer.

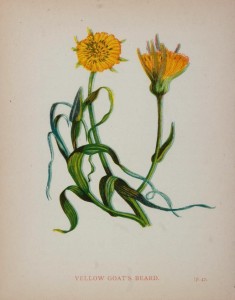

Tragopogon porrifolius (salsify, oyster plant) is a good candidate for Plant 65v. Various Tragopogon species have blue, purple, pink, or yellow flowers. The calyx of T. porrifolius is triangular and the sepals extend beyond the blossoms, so that the blossoms often have a “tucked in” look. The leaves are long and slender. Tragopogon pratensis (middle) has leaves that curl, as does T. pratensis (right). The long parsnip-like tubers of several species of Tragopogon have a medicinal history and can be eaten boiled or roasted. Sometimes Tragopogon has numerous and surprisingly thick side roots.

But what about all the green and white “puffs” surrounding the blue flower? Later in the year, Tragopogon puts out seed heads that are similar to dandelion puffs, with airy white fluff and a hard center. In some species, the center is white, in others, it is dark. Eventually, the fluff blows away, leaving only the center and a slight fringe of withered sepals. Whether the green and white “knobs” represent seed heads is not clear—it’s something of a stretch. Perhaps this is a representation of the knobs after the seeds have flown or perhaps it’s a different, but related plant.

There is an important detail in Plant 65v that points to Tragopogon as a good candidate. The lower leaves tend to clasp the stem. If you look closely at the Voynich illustration, there are wide spots that look like leaves clasping stems, even if simply and crudely drawn.

Plant 65v may not be Tragopogon, but there’s a good chance that it is and, in terms of flower head, leaf arrangement, stem, and root characteristics, it’s a better candidate than Centaurea cyanus.

Posted by J. Petersen