I had hoped to write a whole series on this one specific topic (the Villa d’Este). I have thousands of images and copious notes, but I simply cannot find the time to sort and credit all the images and grammatize my notes. The material has been languishing in my files for nine years, so at the risk of never posting it at all, I have decided to upload it in skeletal form…

Of Water and Worts

buy Clomiphene for cheap  In 2008, as I was familiarizing myself with the VMS plant drawings, and looking at the pool pages, I spent several months looking up all the botanical gardens that were in existence prior to 1520 and, while doing so, also investigated the culinary/medical gardens that were present in most large estates, including castles, universities, monasteries, and medical schools. Some of the ones I found were later than my cutoff date of 1520 but I hoped they might provide clues to earlier structures that inspired them.

In 2008, as I was familiarizing myself with the VMS plant drawings, and looking at the pool pages, I spent several months looking up all the botanical gardens that were in existence prior to 1520 and, while doing so, also investigated the culinary/medical gardens that were present in most large estates, including castles, universities, monasteries, and medical schools. Some of the ones I found were later than my cutoff date of 1520 but I hoped they might provide clues to earlier structures that inspired them.

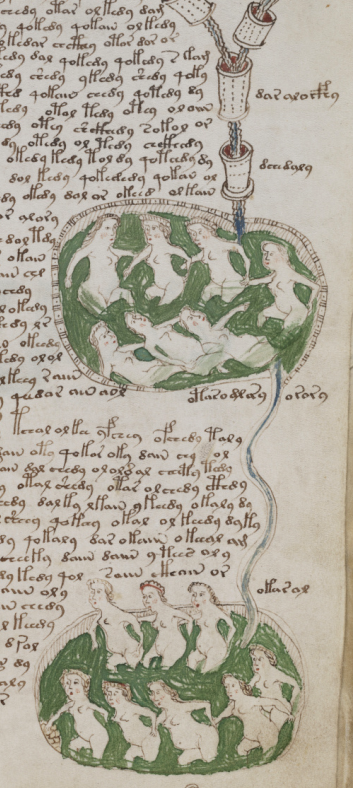

Palladam What motivated me to look into botanical and courtly gardens was the VMS emphasis on plants and water, and several “map” rosettes that looked like they might be related to gardens, as well (particularly the “aerial” view on rosette 9, which resembles a garden design with water flows).

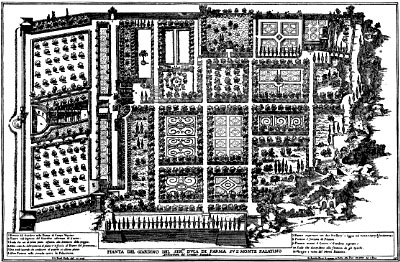

The Farnese Gardens were created on the Capotilline hill in Rome, in the mid 16th century. This shows an aerial view of the garden layout with each section arranged with different geometric shapes. Culinary, medical, and decorative gardens were an integral part of court and institutional life, and gardens with waterworks were particularly popular in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Other parts of the VMS “map” could be interpreted as fountains and pipes. The little decorative element between rosette 6 and 7 (right) might be a fountain and there are obvious parallels to water and streams in rosettes 3 and 7. Other parts look like water spraying and it’s possible that rosette 2 represents a water source with gargoyle spouts around a central column, as were found in many pubic squares.

In my search for medieval gardens that might have a strong connection to water, especially piped water, I explored the Vatican gardens, the Garzoni Gardens, the Versailles gardens, the Dresden fountains, the Salerno, Padua (which were framed by a circular wall), and Verona gardens, St. Petersburg gardens, English gardens (especially ones near Roman baths), the Villa d’Este, in Tivoli, Italy, and many others. I also looked into spa areas in Bohemia, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, and some of the Grecian islands. Information on similar themes in Spain was sparse. They may exist, but in 2008 there was almost no information on the Web about them.

Viva Villa d’Este

The d’Este estate particularly interested me because it had piped water and many Pagan artworks and architectural structures strongly connected to water, nymphs, and plants—reminiscent of VMS plant-and-water imagery in general and to the rosettes page, in particular. One could describe the d’Este estate as “unapologetically” Pagan for reasons I’ll discuss below.

A Brief Background

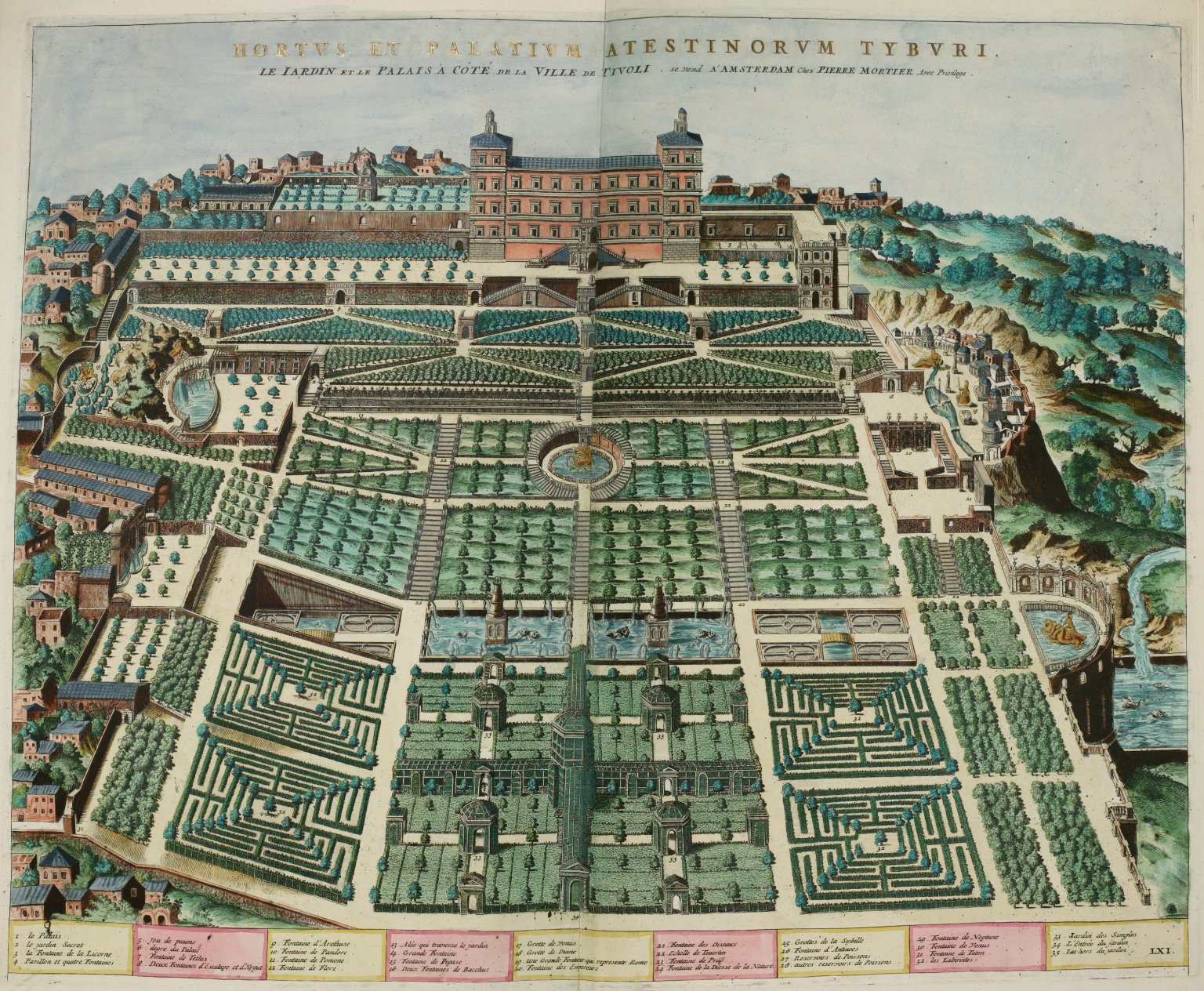

The d’Este family was wealthy, influential, and strongly interested in the arts. The Villa d’Este, in a scenic mountainous area near Rome, was commissioned by Ippolito II d’Este (1509–1572) and even though he was connected to the Roman Catholic church and became a cardinal, he was apparently more interested in Roman history and beliefs than in contemporary Christian customs. As such, the artworks on the estate include Greco-Roman gods, the Ephesian Diana, and round arched Pagan temple pools with nymphs sheltered under archways. Throughout the estate are fountains, cascades, gargoyles, and pools.

Thus, there are many parallels between the d’Este estate and the VMS and rather than blog about each one, as I originally hoped, I’m simply going to list them

The dangling teats/testicles under the nymph on folio 77v is reminiscent of the acorns/testicles/breasts depicted on many ancient sculptures of Diana. It’s difficult to know what the breast-like shapes signify in the VMS. At first I thought it might refer to the she-wolf that suckled Romulus and Remus. Then I thought the figure might represent the Sabine who stopped the fight between the Romans and the native hill people. K. Gheuens has pointed out that it might represent a constellation, in which case Cassiopaea would be a good candidate. On the left, the Ephesian Diana is framed by an arched grotto, as are several of the VMS nymphs, as water streams around her and from the breast-like forms on her chest. Note also that the crown-veil shape framing the head of one of the VMS nymphs could be based on crown-veil shape imagery related to an ancient goddess. [Image courtesy of Yair Haklai, Wikimedia Commons.]

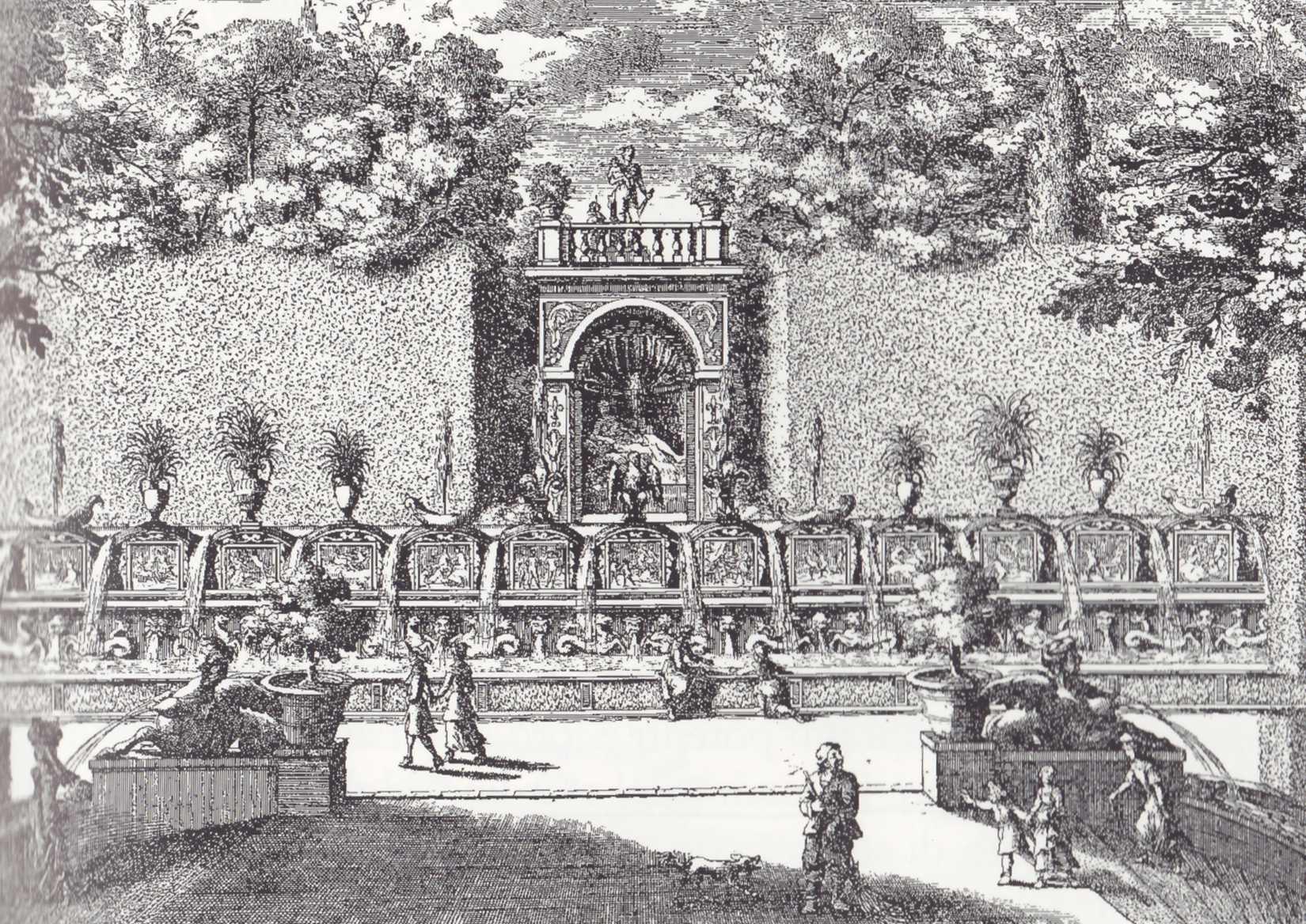

Legendary Greco-Roman figures are framed by archways and numerous fountain works. Trees and water were sacred and intrinsic to Pagan religion, as water was believed to be the birth and dwelling place of goddess nymphs. [Image courtesy of Google Maps Street-view].

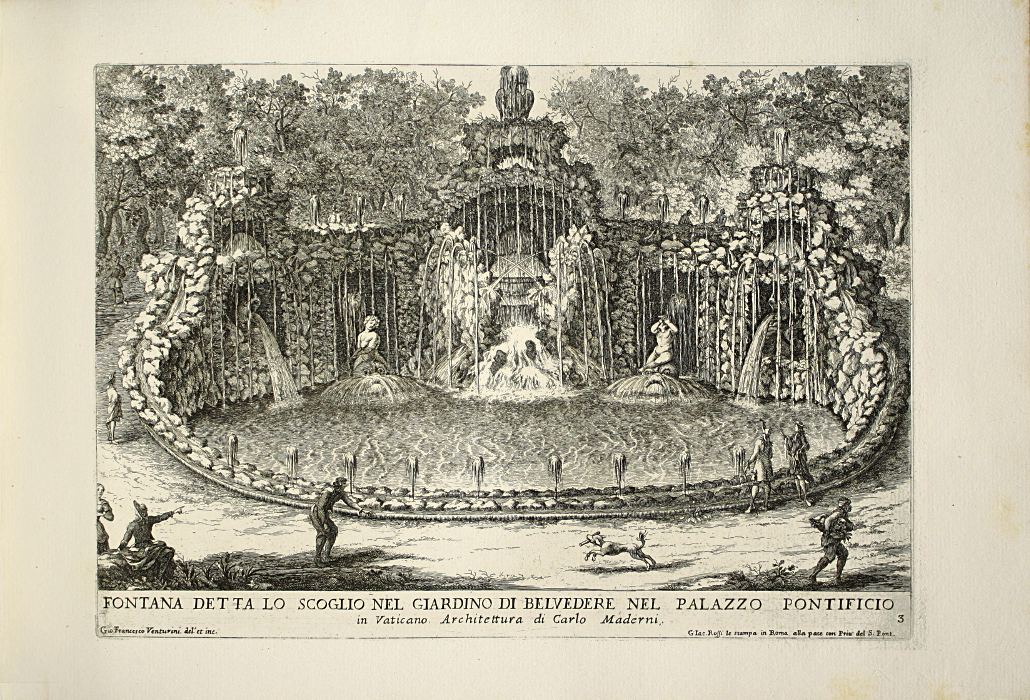

The Della Ovata pond and archways are evocative of Pagan goddess-temple styles. The VMS central rosette, which features a circular structure with stars and decorative “columns” could be an iconic representation of ancient goddess temple architecture. The Falda grotto-style fountain pool (below), built on a similar concept, shows what the rockwork around the Della Ovata may have looked like before the more recent low-wall was added.

Waterfalls and Green Pools

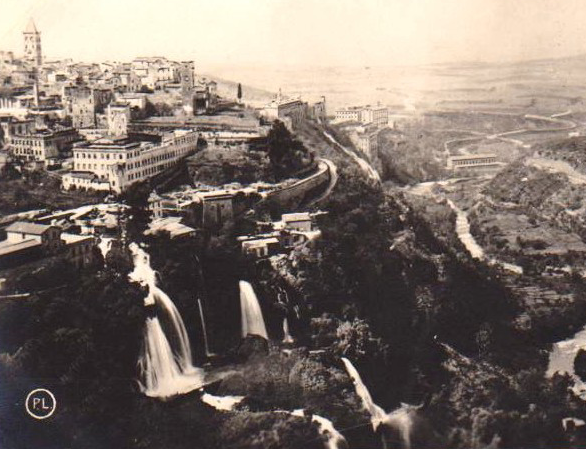

In the middle ages, the Villa d’Este was surrounded by natural wonders: mountains, cliffs, crooked roads, and many rivulets and waterfalls. The VMS is full of “waterfall”, pool, and bathing imagery that bears similarities to this topography. The VMS rosettes page includes many escarpments, and there is a shape between rosettes 4 and 6 that could be interpreted as a fountain. There is also a crooked mountain road connecting rosettes 1 and 4 leading from what might be an eye-shaped mountain or volcano. A similar road leads to the Villa d’Este. Notice the pipes coming out of the VMS volcano-like “mountain” (water was piped down to feed the estate’s cistern and extensive waterworks).

The Cascadia is a scenic landmark in Tivoli, by the Villa d’Este. Notice the green pools and the rivulet connecting the pools, very similar to how green pools are arranged in folios 78r and 81r. The Cascadia lower river has terraced pools, some of which have been shaped with nearby rocks to make them more comfortable for bathing.

This image, from the 1930s, shows the topography of the d’Este estate in Tivoli, Italy, with its many waterfalls and green-water bathing pools. In the 16th century, the gardens were much more extensive.

The pool imagery on folio 78r might represent natural waterholes that have been rocked in for bathing, so it’s difficult to know whether the VMS “pipes” that appear to be feeding the pools represent natural water, or aquaducts and pools constructed to create bathing holes.

Natural water holes existed in the landscape in countless regions, including the Alps, Bohemia, Pozzuoli, and the town of Tivoli, Italy, and there may also have been bathing holes in the Villa d’Este grounds, which were larger in the 16th century than they are now, which makes it very difficult to know if these pool pages are generalized, allegorical, or meant to represent a specific location.

The Villa d’Este had a large culinary/medical garden, similar to those at monasteries. It’s possible that rosette 9 is an aerial view of gardens common to castles, monasteries, and universities.

The VMS map is full of pipe shapes. They come out of the mountain, they surround the central rosette, and they spray between rosettes 2, 4, 6, and 8. No one has been able to convincingly explain the meaning of the pipes or their relation to the rest of the imagery, and they may be allegorical, but if they are intended to be real pipes, here is one thought…

The Villa d’Este was built with some incredible piping systems and waterworks, centuries ahead of their time. They form a lattice underneath the grounds and are not just there to provide water to people and plants, but also to feed elaborate fountains and whimsical waterworks, throughout the estate, some of which were triggered by people walking nearby, so they would be showered unexpectedly as a form of entertainment. The estate was a marvel of hydraulic engineering and is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

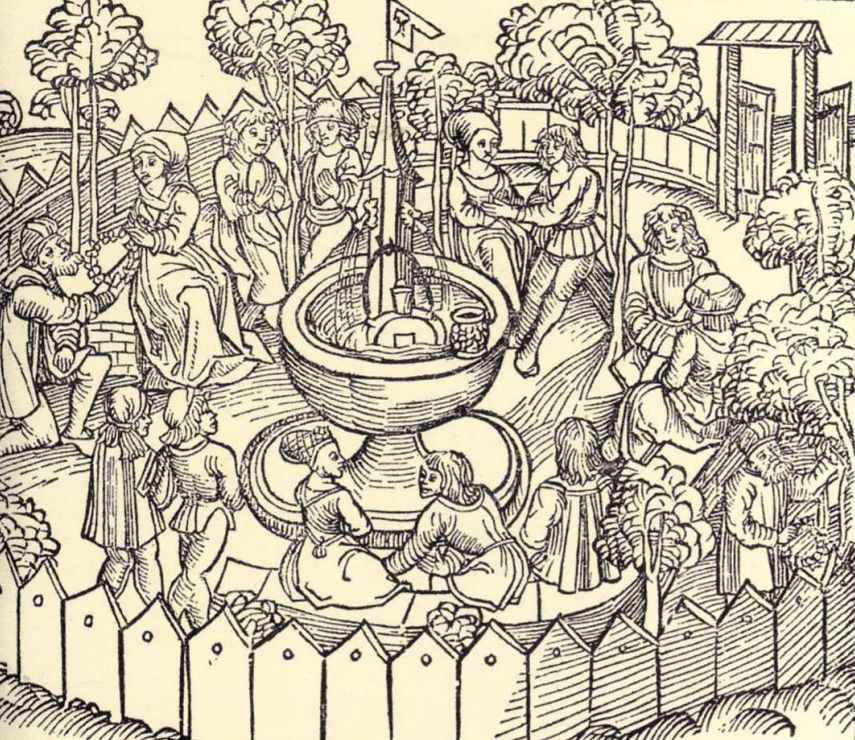

A popular theme in medieval imagery is the courtly garden party, which is often shown as a ringed area with a central fountain. You might notice in the second picture below that the fountain embellishment resembles not only the containers in the VMS small-plants section, but also the VMS “architectural columns with feet” that look like large containers in the central rosette.

A popular theme in medieval imagery is the courtly garden party, which is often shown as a ringed area with a central fountain. You might notice in the second picture below that the fountain embellishment resembles not only the containers in the VMS small-plants section, but also the VMS “architectural columns with feet” that look like large containers in the central rosette.

I didn’t want to constrain my research to Europe, I always search as far afield as possible, but information on medieval spa sites and gardens east of Constantinople or south of the Mediterranean is scarce and was especially scarce nine years ago, but I did find some information on gardens in the Levant, including the area around Jerusalem. The idea of Jerusalem intrigued me because I thought the “mountain” in rosette 1, with its almond-shaped “eye” (similar to an olive pit) might be the Mount of Olives.

The Garden of Gethsemane (image from 1893) is in an arid region, where it’s harder to grow things, but still bears some similarities to more northerly gardens, with a circular design and a fountain-like centerpiece, but I wasn’t able to reconcile many features of the VMS map with this part of the world.

Summary

I hate to stop in the middle of a topic, I have much more information but so little time, so I’ll end by saying I wasn’t able to convince myself that the rosette map was the Villa d’Este or any of the similar gardens that preceded it (many of which no longer exist except in verbal descriptions). The reason I’m not sure is because I couldn’t reconcile what looks like compass points (the two suns and the T-O map) with the layout of the d’Este estate. It’s close… the “mountain”, the water, the escarpments, and some of the other features could be related to real physical features, but it takes a bit of wrangling, and there is some imagery that doesn’t quite seem to fit this location.

Villa d’Este was one of many ideas, and I’m keeping it on the table, but it post-dates the VMS by more than a century, and information on its predecessors is scanty. Also, I subsequently found a location that MIGHT explain the rosettes page better than Villa d’Este, a location that better fits the compass points. It doesn’t have extensive waterworks, but it did have piped water and nearby natural waters, and some of the other features on the rosettes. Unfortunately, I can’t spare time to describe it today. It will have to wait for another blog.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2017 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

Surely one of the better near-hits provoked by the Voynich. With some wonderful sightseeing along the way 🙂

I think certain sections of the MS have been designed to work on various levels. On the surface, it looks like a green water pool party, but upon closer inspection it doesn’t appear to be that simple.

Now the rosettes foldout, that’s something else stull. Maybe you are right that it does look like a garden layout. But as you say, there are other elements which make this unlikely. Also the middle citcle must represent a city of some sorts.

This is one of the most Voyniched-up parts of the manuscript and I hope somebody will be able to explain it all one day…

Yes, possibly a city.

The first time I saw it, it reminded me of Constantinople or Baghdad, but then I noticed the “pillars” had feet, like the containers in the small-plants section and that made me wonder if I was assuming too much about scale. Looking at it again, the inverted blue dome with stars reminded me of a temple and I must have collected hundreds of images of the insides of domed ceilings looking for matches to anything in the VMS that was vaguely dome-like. It seems that every trail has a dozen branches.

After that, I wondered if the whole thing were metaphorical (like the mythical “New Jerusalem”) and the mountain/volcano/colliseum rosette might possibly be a hell-mouth rather than real geography.

In other words, to this day, I have no idea what it represents, but I have some possibilities that I’ll try to get posted.

-JKP –

For a considerable time I thought it likely – after treating much else – that the enclosed sparkling water amid those incense-burner like things was meant for the dam of Mar’ib. Now I think – like you – it’s meant less literally, and probably denotes Arin. For historical reasons, the two are not necessary mutually exclusive identifications, though I guess I may have to opt for one or the other some time.

During the time you spent looking at medieval and later gardens, did you find any good historical-botanical sources? I’m trying to find if any of the pre-1438 gardens’ records exist, especially in connection with imported exotics. Not much luck so far. I guess most people didn’t keep records of plant-purchases for hundreds of years. Mere tradesmen stuff.

It’s so long ago I can’t even remember if I was able to locate garden records that predate the VMS. I found a little bit of information on two Italian gardens that may have inspired Villa d’Este, but there really wasn’t much. I also found a few textual descriptions of garden layouts, sometimes written by visitors from other villages, or notes by the person designing them. There are some older diagrams, but accurate drawings of gardens weren’t very common until after ca. 1450. Some of the early maps include rough sketches of castle gardens but it’s hard to tell if they are accurate or iconic.

There was a monk in England who cataloged a number of the plants in a monastery garden, but I don’t think he included any information on where they got the plants.

There was significant communication among monasteries all over Europe (and presumably those in the more distant colonies), especially between Bury St. Edmonds, England, and St. Gall, Switzerland. They actively shared letters and manuscripts, so I assume they probably shared seeds, as well.

One of the things I’ve learned about culinary and medicinal plants that grew in these gardens is that the majority were common plants, ones that grow wild, often in abundance (e.g., oregano, thyme, lemon balm, galiopsis, viola, sonchus, lactuca, brassica, petroselinum, veronica, clover, borage, allium, etc.) and perhaps that is because wild-crafted seeds are easily harvested and sown without having to buy them.

I’ve read correspondence among some of the later (16th and 17th century) gardeners and botanists in which they expressly ask their friends and colleagues to bring back seeds, bulbs, and dried specimens from more distant locations, so this may have been customary in earlier times, as well. Seeds are easy to carry, which might explain the lack of records regarding medieval plant purchases.

I see you catching on to the Este’s. Well then don’t give me such row then!

I did my research on the Villa d’Este in 2008 and the time period and location I’ve written about in this blog are quite different from the one you mentioned on the forum.

Also, to be clear, I never gave you row about bringing up the d’Este family—I expressed concern about the questionable way you equated VMS glyphs to decorative shapes in tarot cards.

If you really are interested in D’Este maybe we could work together instead of argue!

Academic critique is a part of presenting your findings. Since you are posting and selling your results to the public, you have to expect feedback and commentary on questionable research methods or results.

I originally thought about Botantical gardens and activately searched for a suitable candidate, but then my thinking turned in quite a different direction. I haď some idea as to where I expected to find this specific rosette, but could find nothing that fitted in terms of a garden. Actually I think the first Botantical gardens date from a later period than the manuscript. Anyway I began to look at monastic cloisters viewed from above adjoining a herb garden. “X shaped” cloisters are rarer than “+ shaped cloisters. I found a candidate which closely resembles this rosette and other details fit neatly. This is a far less grand possible identification than the gardens of Este, but fits the time period much better.

Perhaps interesting to recommend for additional reading the article “Orto dei semplici: botanical gardens in Italy”. http://voynich.webpoint.nl/?page_id=4928