Eureka I Think I’ve Found It

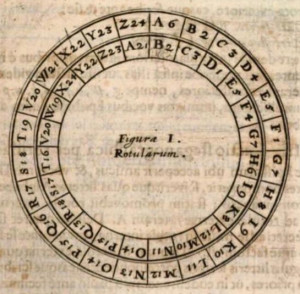

Every few months, someone claims to have decoded the baffling text of the Voynich Manuscript. Many eager code-breakers seem to think it’s enough to crack the door a couple of inches and let others do the actual work of decrypting it according to their revelatory method. To date, no one has published even two paragraphs of text that can be generalized to the document as a whole and some have offered only a few words that have yielded not even a single decrypted sentence.

Every few months, someone claims to have decoded the baffling text of the Voynich Manuscript. Many eager code-breakers seem to think it’s enough to crack the door a couple of inches and let others do the actual work of decrypting it according to their revelatory method. To date, no one has published even two paragraphs of text that can be generalized to the document as a whole and some have offered only a few words that have yielded not even a single decrypted sentence.

Even methods that show promise are applied to the inscrutable text in inconsistent ways or result in text that doesn’t have the flow of natural language and can be interpreted according to whim rather than to an objective standard. Until someone describes a method that can be adapted by others and generalized to at least a few pages, the VMS text remains unsolved.

When the Tail Wags the Dog

I’ve never made any assumptions about where the VMS was created or by whom. I look for trails and follow them wherever they happen to lead and, if they run cold, I look for another and follow that. Thus, it surprised me that Edith and Erica Sherwood made this statement several years ago on their Voynich site with regard to plant identifications:

“Acting on the premise that the Voynich Manuscript is a 15th century Italian manuscript, we limited our selection to plants native to Europe or at least the old world and excluded all plants from the Americas.”

It’s entirely possible that the VMS originated in Italy, and maybe it makes sense to start in the most likely locale, but why begin with a limited set of data when you are in the information-gathering stage? It’s possible the Sherwoods had a good reason for limiting their search for plants, maybe they knew something about the VMS that others didn’t, but my feeling is that if you’re starting out, it’s sometimes better to cast a wide net and let the data lead you rather than putting artificial constraints on the search.

There are times when it makes sense to impose limitations, if the scope of a problem is intractable due to time or resources, but identifying plants isn’t an intractable problem. Botanists do it every day, often with plants for which the origin is unknown. If you choose to keyhole your research, do it in a reasonable way or someone will come along and upset the apple cart like this…

A New World Origin

One of the more interesting ideas on the origin of the VMS was offered by Arthur O. Tucker, botanist, and Rexford H. Talbert, an information technologist with an interest in chemistry and botany. Tucker and Talbert’s 2013 paper was published in the American Botanical Council’s journal, the HerbalGram. A New World origin was proposed, with the suggestion that an extinct form of the Nahuatl language underlay the text.

This is a cool idea, if you consider someone trying to write a 16th century Aztec language with Latin characters might make up new characters to represent sounds not found in Spanish or Latin. That the VMS could have been created somewhere other than Europe is a reasonable hypothesis. The VMS was found in a Jesuit library and missionaries (Jesuit, Franciscan, Benedictine and others) were often the first to set up schools and housing in new colonies in both the far east and the west, and a number of them were interested in recording natural history. It’s also reasonable to consider that the text and drawings in the VMS might have been added to the parchment years after the parchment was prepared. There may even be small caches of centuries-old parchment that remain unused.

Pinning Down that Pesky Date

Radiocarbon dating is a very good scientific tool and has been greatly improved since it was first introduced. Scientists rarely use carbon dating by itself to determine the age of a document, they look at many factors (often hundreds of clues are considered together before estimating a date) but even by itself, carbon dating can sometimes yield useful information.

When the VMS style of drawing and writing, the cultural references in the pictures, the ink, parchment preparation, carbon dating, and other factors are taken into consideration, they point to the early 15th century. The Voynich Manuscript probably wasn’t created earlier than that (you can’t write on vellum/parchment that is still on the hoof), but there is a possibility that it was created later than the estimated dates, if the parchment (and ink) sat for a while before being used. Ink doesn’t last as long as parchment, it will dry out if exposed to air, but even ink can be stored for a couple of decades (maybe longer) in glass containers with good stoppers.

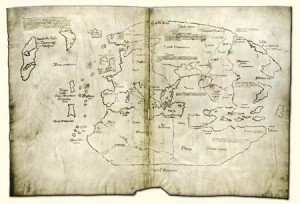

Carbon dating narrowed down the origin of the materials used to create the VMS to between 1404 and 1438. Interestingly, radiocarbon dating on the famous Vinland map (a Nordic map of the New World) dates it to the early 15th century as well.

Carbon dating narrowed down the origin of the materials used to create the VMS to between 1404 and 1438. Interestingly, radiocarbon dating on the famous Vinland map (a Nordic map of the New World) dates it to the early 15th century as well.

Like the Voynich Manuscript, the Vinland map has been called a hoax, especially as it appears to have been created about four centuries after the original Viking voyages to the New World, but it’s also possible it is a copy of an older map that was passed down after the original voyages and may yet have some historical importance. Whether the VMS is historically important beyond being a curiosity depends in part on how much, if any, of the text can be deciphered.

It’s not practical to apply radiocarbon dating to every page of the manuscript, but the results from the samples were quite consistent. Whether the VMS was a short- or long-term project is difficult to assess. There are some puzzling anomalies in the text and illustrations that suggest it may have been created by more than one person. Perhaps it was begun in one decade and finished in another. But is it possible that it was created a century later than the ink and parchment, the clothing styles, and the style of drawing suggest? Except for some exploratory pillaging and slaughter of indigenous people in the late 1490s, the New World wasn’t colonized by Europeans until the 16th century. Could the VMS have been created later than the journeys of Columbus?

Herbal Tradition and New World Plants

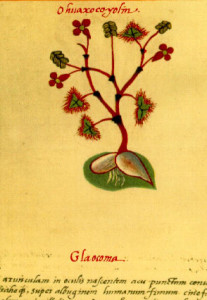

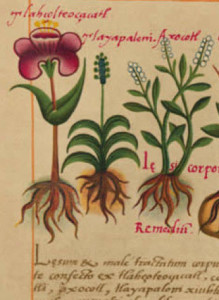

The first New World herbal manuscript that has survived to the present day is the Codex Badanius, written in Nahuatl, in 1552, by Martinus de la Cruz, a physician at the College of Santa Cruz in Tlaltelolco. The Voynich text even looks a bit like Nahuatl, which has some linguistic rules that create a higher level of repetition than is characteristic of English.

English has many loan words from other languages, including old Norse and French. In fact, in the 15th century, a number of words in Middle English were spoken as they were in old Norse. Nahuatl gives the impression of being more homogenous than English (as Korean was before Chinese commercial terms and English computer terms began interfering with the internal consistency of the language). As cultures mingle, the basic “logic” of a language gets lost in the jumble of new words.

So what is the connection between the Voynich Manuscript and Spanish colonies at the southwest corner of the Gulf of Mexico?

In their paper, Tucker and Talbert state that they were

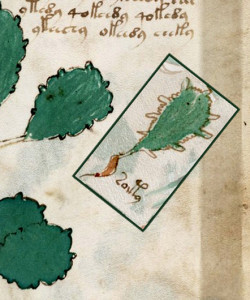

“… initially drawn to plant No. 8 of the 16 plants on folio 100r; this is obviously a cactus pad or fruit, i.e.g, Opuntia spp., quite possibly Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill. (Cactaceae) or a related species. Thus, is quite easily transliterated as nashti, a variant of nochtli, the Nahuatl (Aztec) name for the fruit of the prickly pear cactus or the cactus itself.”

A Thorny Conundrum

Based on their assertion that plant f100r–8 (right) was obviously a cactus, I consulted folio 100r and immediately questioned how so little information could result in such a definite ID. Given the limited artistic skills of the VMS illustrator, it could be many things and this plant didn’t look spiny to me, it looks knobby.

Based on their assertion that plant f100r–8 (right) was obviously a cactus, I consulted folio 100r and immediately questioned how so little information could result in such a definite ID. Given the limited artistic skills of the VMS illustrator, it could be many things and this plant didn’t look spiny to me, it looks knobby.

I was also curious as to how the VMS text next to the plant “easily transliterated” as nashtl. If this says nashtl, why can’t we translate the other plant names on the page using the same system of substitution? How do the researchers know this is a label for the plant rather than an instruction for processing it or perhaps a word to indicate which part of the plant is used? Maybe the text has nothing to do with the plant.

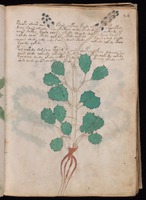

I also recalled there being a plant with a similar leaf structure on another page and sought out Plant 26r for comparison with f100r–8. It has somewhat pear-shaped leaves with regularly spaced, rounded protrusions. The margins are drawn darker than the plant on f100r and the area between the big bumps isn’t as ragged, but the essential shape of the leaf is similar.

I also recalled there being a plant with a similar leaf structure on another page and sought out Plant 26r for comparison with f100r–8. It has somewhat pear-shaped leaves with regularly spaced, rounded protrusions. The margins are drawn darker than the plant on f100r and the area between the big bumps isn’t as ragged, but the essential shape of the leaf is similar.

There are other instances in the VMS where a smaller version of a larger plant can be found in the sections near the end of the manuscript, so it’s possible that the same plant might appear in two places. I’ve added the plant from f100r to 26r so you can see the similar shapes of the leaves. They’re not identical, but they’re close enough to propose that they might be the same plant and if they are, this is definitely not a cactus plant. It has a slender stem, long petioles, and flowers on long spikes. This plant would wither and die in a desert environment.

There are other instances in the VMS where a smaller version of a larger plant can be found in the sections near the end of the manuscript, so it’s possible that the same plant might appear in two places. I’ve added the plant from f100r to 26r so you can see the similar shapes of the leaves. They’re not identical, but they’re close enough to propose that they might be the same plant and if they are, this is definitely not a cactus plant. It has a slender stem, long petioles, and flowers on long spikes. This plant would wither and die in a desert environment.

Even if Plant 26r and f100–8 are different plants, I think Plant 26r demonstrates that a pear-shaped leaf with protrusions can be something other than a cactus plant.

buy provigil from mexico Summary

Cactus plant symbolically representing Mexico in the Codex Osuna, with Nahuatl in Latin script underneath.The Aztecs had a pictorial written language prior to colonization by Spanish-speaking Europeans, so the sounds were transliterated into the Latin alphabet and taught to young Aztec boys.

I’m not going to go through the Tucker and Talbert arguments point-by-point because it would be too long for a single blog post, but I’ll leave you to read their article, if you haven’t already (it’s an interesting read), and to think about whether the VMS plants are accurate and specific enough to say whether they correspond to New World or Old World plants.

Also, make note of Tucker’s statement about how botany students tend to draw by emphasizing the parts they particularly notice. This is something I’ve observed in a more general sense, as well, and it may explain some of the more bizarre physical traits of some of the VMS plants.

There were similar plants growing in both Eurasia and the New World in the 15th century, including violas, ivy, plantain, saxifrages, St. John’s wort, sundews, water lilies, terrestrial lilies, alliums (onions), loosestrife, chicory, wild lettuce, dodder, juniper, calendula, and solanum (nightshade). Whether the VMS represents New or Old World plants (or both) is still up for debate. I’m leaning toward Old World based on studying the plants for a couple of years, but if the plant that looks like Ricinus (an Old World plant) turned out to be a New World chestnut tree, for example, that would have a substantial impact on our understanding of the VMS.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2016 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

……Cactus plant symbolically representing Mexico in the Codex Osuna, with Nahuatl in Latin script underneath……

Looking at the cropped photo of the Cactus Plant, with small sample of text;

Does this appear to be 2 more refined “gallows” characters to anyone else?

It puts me in mind of a slightly sloppy “tl”, but perhaps the standard in the place and time.

The VMS has many of these, albeit in a less refined hand – perhaps parts of the VMS were prepared in “The Field”?? Is that something that was done 600 years ago?