The Tip of the Tongue

When I saw the VMS Leo symbol with its tongue sticking out, it reminded me of a South Pacific tongue dancer I saw when I was a teenager. He was dressed in colorful native attire, with tattoos and face paint, a spear in his hand, and looked amazingly fierce when he came over to where we were sitting on the ground and showed the whites of his eyes and displayed his tongue.

When I saw the VMS Leo symbol with its tongue sticking out, it reminded me of a South Pacific tongue dancer I saw when I was a teenager. He was dressed in colorful native attire, with tattoos and face paint, a spear in his hand, and looked amazingly fierce when he came over to where we were sitting on the ground and showed the whites of his eyes and displayed his tongue.

The VMS lion isn’t as fierce looking as the tongue dancer, but the image made me curious about how many other zodiac Leos had their tongues sticking out. After scouring the digital manuscript archives and collecting more than 100 medieval zodiac cycles, I only found nine with protruding tongues, and only two of those had their tails curled between their legs. Another thing I noticed with all the Leos except one or two from the Mediterranean region, is that they had full manes.

The VMS lion isn’t as fierce looking as the tongue dancer, but the image made me curious about how many other zodiac Leos had their tongues sticking out. After scouring the digital manuscript archives and collecting more than 100 medieval zodiac cycles, I only found nine with protruding tongues, and only two of those had their tails curled between their legs. Another thing I noticed with all the Leos except one or two from the Mediterranean region, is that they had full manes.

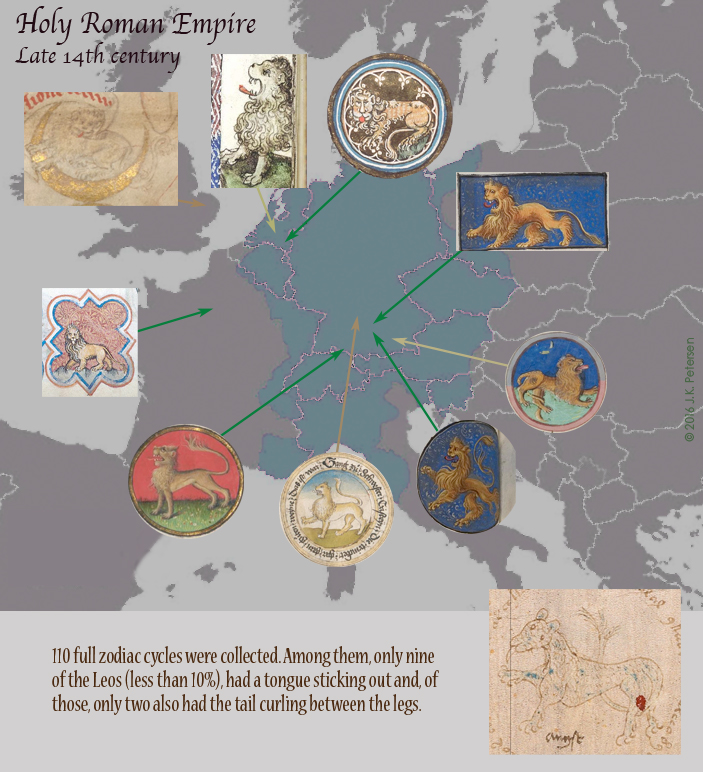

None of the tongue-Leos had a tree in the background, either, so it seems the VMS Leo is unique in a number of ways. You can see the zodiac Leos I found with tongues in the following map, superimposed on political boundaries for the late 14th century.

The tongue Leos were mostly from central Europe with a few in France, the Netherlands, and eastern England.

It’s not even certain whether the VMS symbol is a lion. Sometimes spotted cats such as cheetahs are substituted for lions as zodiac symbols, but these are not common, either. The VMS Leo diverges from tradition and the tree in the background looks like it might be a palm tree rather than a deciduous tree, entirely appropriate if you consider lions are mostly concentrated in hot countries.

It’s possible the VMS lion was inspired by zodiac illustrations of lions from the Mediterranean, which sometimes don’t have manes. There are also non-zodiac lions that have their tails curled through their legs, but whether the VMS illustrator based the drawing of Leo on having seen a lion in real life, or from studying a Mediterranean manuscript, is difficult to determine.

Since the VMS Leo resembles north-central European Leos in other ways, maybe the illustrator simply chose to draw a lion without a mane, just as he or she chose to draw a pair of crayfish (instead of a single one) as a cancer symbol, something I have yet to see in any other zodiac. Resemblance doesn’t always guarantee that a drawing was imitated.

The maned lions we think of as African lions used to inhabit southern Europe but were crowded out by hunting and loss of habitat between the time Stonehenge was built and about a century BCE except for a few that remained in the Caucasus until the 11th century. Cave lions, which looked more like the American mountain lion, were extinct long before the African lion disappeared from Europe.

We know that the VMS illustrator was exposed to zodiac traditions in books or perhaps on the floors and walls of cathedrals or temples, but we don’t know if the way the symbols are drawn is based on other zodiacs or on illustrations and carvings of animals and mythical heroes not directly connected with a zodiac cycle.

We know that the VMS illustrator was exposed to zodiac traditions in books or perhaps on the floors and walls of cathedrals or temples, but we don’t know if the way the symbols are drawn is based on other zodiacs or on illustrations and carvings of animals and mythical heroes not directly connected with a zodiac cycle.

Many western zodiacs, in the north and the south, included labors of the month, and sometimes those labors included animals like goats, sheep, and others, so they too might have inspired an inventive person to create zodiac symbols that were mostly like others but also different in some unique ways.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2016 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

JK

I’ve yet to be convinced that the series was intended to represent any astrological series, and until someone later added month-names in Occitan or Judeo-Catalan, I don’t think it would have been taken for an astrological zodiac.

Not surprising that you have found no exact match if only considering zodiacs; as it happens, there’s an echo of the body-type in some Carolingian manuscripts, but the in MS Beinecke 408, shown with tongue protruding and paw uplifted is not medieval European, even if heralds adopted the ‘bloody tongue’ as a motif. Apparently there it signifies the roar and not the wish to eat people. 🙂

The ‘red splash’ on the Voynich feline shouldn’t be presumed an accident; as I I’ve demonstrated, it occurs on other Caroline and Ottonian works (though not many); its purpose is apotropaic.

After about the tenth or eleventh centuries, such marks aren’t seen, so our fifteenth-century manuscript is faithfully reproducing imagery and associated customs from an earlier time. Some of the calendar’s figures are modernised, though mainly the Archer.

I wont refer you to my posts on the subject; I’m sure you can find them if you wish.

PS – for animals with curled tails, you should look at some Jewish manuscripts of the 12th-14th century, and carvings in wood and ivory. Glass-engraving too. Some images already posted from each, as far as I recall, but I treated the Leo yonks ago, so the posts are likely to have an original date of 2010-11 or so, though I might have reprinted some or all at voynichimagery.

Thank you for your brilliant work on VMS, JK Petersen!

Just one comment: There’s no tree in the background of the lion. The “tree” is the tip of the lions tail (visible from the precisely adequate curving of the lines). And of course is this chapter about Zodiac signs (@DN O’Donovan). As astrologers, we recognize them at first sight, really no doubt. Even correct astrological order, as far as I see – except of the starting point with Pisces. We start with Pisces follower Aries. Kind regards,

Susanne

Yes, I know, we’ve actually discussed this very subject on the Voynich.ninja forum and someone explicitly asked me if I thought that was a tree and I answered technically “no”, I think it’s a tail, but… there are so many aspects to the VMS drawings that seem to have double meanings, I think it may also have been deliberately placed that way (almost straight up) with the tip of the tail drawn in a palm-leaf-like way to “suggest” (if not directly express) a tree.

If you are familiar with medieval astrology, then you know that there are some zodiacs that have a tree placed in exactly that way behind the animals and also that the tails are usually more naturalistic or drawn as medieval “flower tails” (and the VMS cat-tail is a little different from most of them).

I often refer to it as a tree because I suspect it might be both, possibly to indicate the habitat of the cat (which is not necessarily a lion).

The continuity of the line and the irregular “bushiness” (considering the inherent artistic aptitude of the illustrator) leads me to strongly agree with Ms. Riedel.

Thank you J. K. Petersen for the most “learned” (for lack of a better word) analysis of the VMS. I have not encountered a better paleographic analysis and cannot wait to see your personal transcription.