14 February 2020

This is one of the VMS plant IDs I left blank in 2013 because I simply couldn’t find an explanation for the root shape. The plant has always looked to me like Tanacetum (or maybe Achillea), but I wanted to figure out the root before posting and was never completely sure if it was an angel, a bird, or something else. Now I realize it might not matter… there might be enough references in the style of the flower to help us understand the meaning behind it.

But first, let’s look at the VMS drawing…

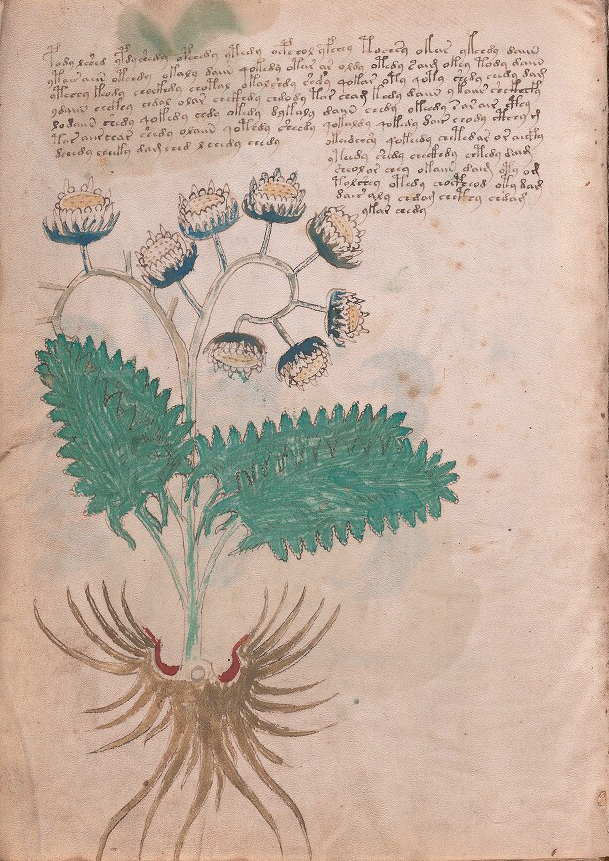

Plant 46v

Plant 46v is drawn toward the left of the page, as though space were left for more text that was never added. The text itself is a bit unusual. There is a right-side column that extends downwards and almost runs into the plant rather than following the shape of the plant. It looks like the text may have been added in two passes, a chunk on the left and a narrowing chunk on the right.

The drawing is fairly large and clipped at the bottom. The size of the flowerheads appears to be exaggerated (perhaps to show the details?). The stalk curls in a way that is not common to very many species—it might be mnemonic or stylized. A few of the individual stalks end abruptly, without flowers, an intriguing detail that might be important.

Coloration

The painting is rough, but the choice of colors indicates some thought. The stalk has clear green on the bottom, shading to a pale grayish-brown on the upper stalk, with blue on the individual flower stalks, and a darker blue for the calyx. The root is a medium brown with a light section where it connects to the stalk, and two red patches on either side.

The leaves are somewhat fernlike, with slight tails, and carefully drawn individual leaf serrations. The leaf stalks are concentrated at the base. On the leaves themselves, almost hidden by paint, are some lines that might represent hairs, veins, or ridges.

In fact, the whole drawing seems somewhat stylized (not just the root, but also the flower stalk and, to some extent, the leaves). To me, the root looks like an angel or maybe a bird and other researchers have suggested it might be a bird. What is provocative about it is the round circle in the “neck” and the red lining on the “shoulders”. These are not accidental details. The round part almost looks like an attachment point, as one might see in a tool or a piece of folding portable furniture.

When I look at the drawing from a distance, it reminds me of Tanacetum or Achillea. Both are in the aster family and have button-like flowers and serrated somewhat frondy leaves. The flower-heads and the serrated leaves in the VMS drawing seem consistent with these plants, but a Voynich researcher had another idea that I think has merit…

Prior IDs

I don’t agree with Edith Sherwood’s 2015 ID. She suggested Geum urbanum (wood avens), which is a plant in the rose family, but the flowers of G. urbanum are not the same shape as the VMS drawing. They have five petals that splay out (see below-right), and the flowerheads are more discrete, and they do not tend to cluster on the same stalk. The palmate leaves don’t match the VMS drawing very well either. She has an earlier ID (2008) suggesting a different plant (Inula conyza), which fits the drawing better, so I’m not sure why she changed the ID.

I think the button-like flowers in the VMS drawing look more like asters than roses, and the VMS leaves are clearly not palmate (there are other VMS drawings that have well-defined palmate leaves, so clearly the illustrator knew how to draw palmate leaves).

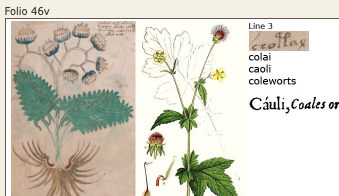

Other IDs

On the Voynich.ninja forum, Ellie Velinska mentioned costmary (Tanacetum balsamita). I like this ID. Costmary has finely serrated leaves and button-like flowers. I think Velinska mentioned a bird in the root, but I had been thinking it might be an angel. Either way, it looks more mnemonic than natural.

In Renaissance-era herbals I have noticed that costmary is sometimes listed under the older name of Chrysanthemum balsamita. Costmary is the Bible-leaf plant (the fragrant leaves are dried and used as bookmarks), and the French name for costmary is Herbe Sainte-Marie (referring sometimes to Mary Magdalene, other times to Mary, mother of Jesus). It was used medicinally in the Middle Ages, and also as a flavoring (hence the alternate name ale-cost).

Velinska’s ID of costmary fits well in almost every way. I wanted to endorse it, but there is one troubling detail…

Costmary is an eastern plant. It is common in Asia but was not introduced to Europe until about the 16th century. It did exist in a few places in the Caucasus, but may not have been abundant, as there were other more common species of Tanacetum that grew in this region, and plants are always competing for habitat. So I tried to find costmary in medieval herbals to see if I could support Velinska’s idea, but found it difficult to find any examples. Those that most resemble it are probably sage, but for the record, here is what I found…

Tracking Down St. Mary

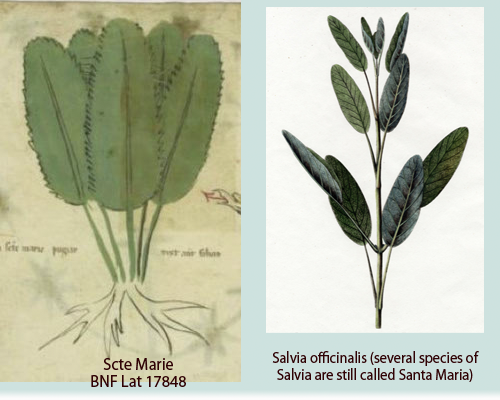

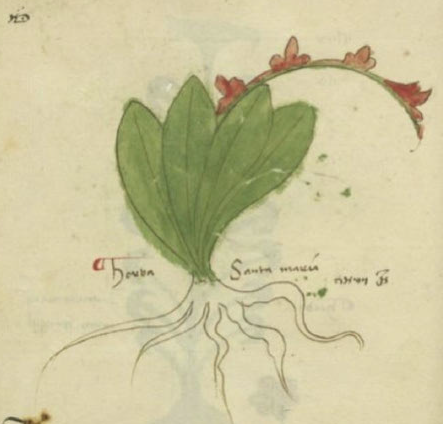

There are many plants called Sancte Maria/Santa Maria (including Dysphania ambrosioides, Solomon’s seal, and some species of Thymus) and the Linnaean system didn’t exist yet to help distinguish them. Most of the medieval drawinngs labeled Santa Maria show forget-me-nots or Solomon’s seal, or do not include flowers (which usually means the flowers are not a prevalent or useful part of the plant).

In medieval herbals, drawings labeled Santa Maria tend to depict leafy plants (which, unfortunately, are very numerous and hard to distinguish from each other), but it’s possible some of them are sage (Salvia), which is often drawn without flowers and called Santa Maria.

There are numerous plants in medieval herbals with flowers that are similar to the VMS 46v. Feverfew, chamomile, and Tanacetum vulgare are common, but they are usually labeled in a way that they can be recognized and I have not found one that can be unambiguously pinpointed as Tanacetum balsamita.

A New Drawing of Santa Maria

Then, while looking through my copious files on medieval plants, I noticed that around the middle of the 15th century, a new drawing labeled Santa Maria shows up in a number of herbals. I couldn’t find it in the older references. Could this be costmary?

Unfortunately, the drawing doesn’t look like costmary, which is an aster. The mystery plant has a single long stalk with flame-like flowers (other versions of the drawing also have orange or red flame-like flowers). It looks more like Gladiolus or Salvia than costmary, so if it is costmary, it’s quite a bad drawing, even compared to other medieval drawings, and since most of the herbals have reasonably accurate drawings of tansy and feverfew (which are similar to costmary). I’m inclined to think the drawing on the right is not costmary, but maybe one of the red salvias.

Other Possibilities

The Tanacetum plants, in general, are a good match for VMS 46v. Many of them have frond-like sawtooth leaves and button-like flowers and, as mentioned, similar plants like tansy and feverfew are commonly found in medieval herbals. For the VMS plant, I was leaning more toward tansy than feverfew, but there are some varieties of feverfew that have shorter-than-usual petals and button-like centers, so it cannot be entirely eliminated.

I’m tempted to include Arabis collina on the list of possibilities. The leaves are a good match and the flower-stalk curls, but unfortunately, the flowers are wrong:

There is another species to consider. Achillea (also known as yarrow) has clusters of button-like flowers and finely serrated or frond-like leaves (depending on the species). It is widely distributed across Asia and Europe, and has much in common with the VMS drawing.

Achillea comes in several colors, including pink and red, but most varieties are yellow or creamy white. On some species, the flowers are like tansy, other times they are like chamomile. The leaves are sometimes feathery, sometimes more solid, and there are even woolly varieties. This plant is often included in medieval herbals under the name Millefolium:

Cotula is another possibiity. It has button flowers (there are quite a lot of asters with button flowers, sometimes called “rayless asters”), but the leaves are typically slender and smooth-margined, so the leaves are not a good match. Acamptopappus species also have button flowers, but it’s a desert plant (and American in origin), and the leaves are quite slender and small.

So I am still uncertain about the identity of 46v, if examined from a naturalistic point of view, and even thought costmary might not have been known in Europe in the early 15th century, it’s still one of my favorite IDs because the idea of an angel in the root would fit well with the name. A bird would too, if we are thinking in terms of Mary’s ascension and bird-drawings of the Holy Spirit.

But what about the curled stalk?

This is a question I’ve been wrestling with for some time, and another reason it has taken so long to post this blog. Is the curled stalk a characteristic of the plant, or is it a decorative embellishment?

There are plants with curled stalks (Arabis, Heliotrope and many others), but they don’t usually have rayless flowers, and the stalk on the right of the VMS drawing has exactly seven flowers (a number important to medieval society).

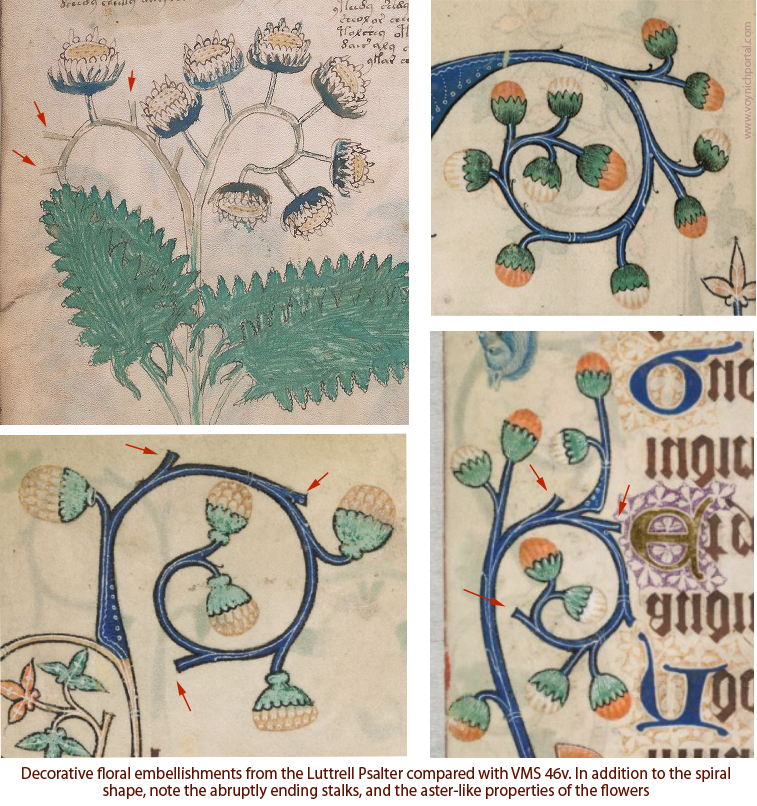

I’m leaning toward 46v being a stylized drawing, especially when I see decorative floral elements in manuscripts such as the ones below (I have flipped them so they face the same way as the VMS flower). In terms of iconography, take note of the clipped stalks:

A Connection to Medieval Cosmology?

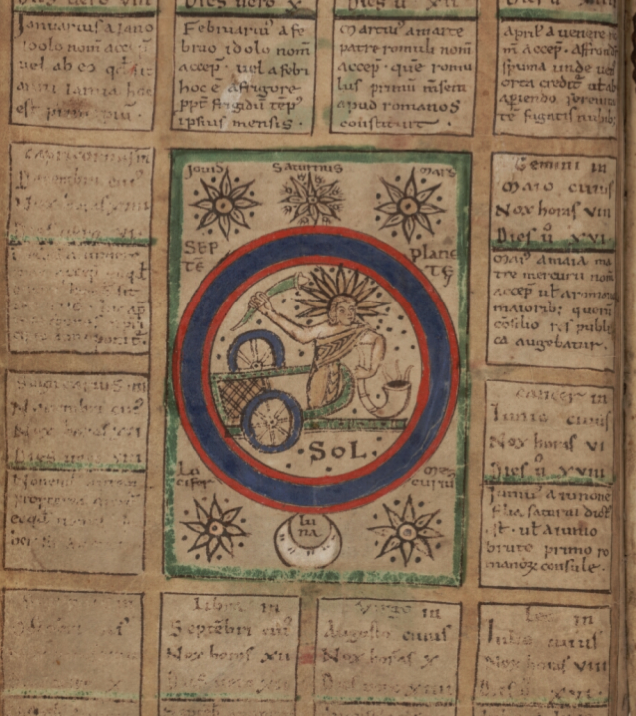

I kept wondering why the VMS illustrator spun the flower stalk in a loop and put seven flowers on the right stalk and one on the left. I knew it was common for medieval and post-medieval emblems to include seven stars representing the “seven planets”. In medieval cosmology, the earth was the center of the universe, orbited by seven “stars”.

Does the flower on the left represent the earth, and the seven flowerheads on the right the seven “stars” (or “planets” as they were conceived at the time), which were defined as Moon, Mercury, Lucifer/Veneris, Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn?

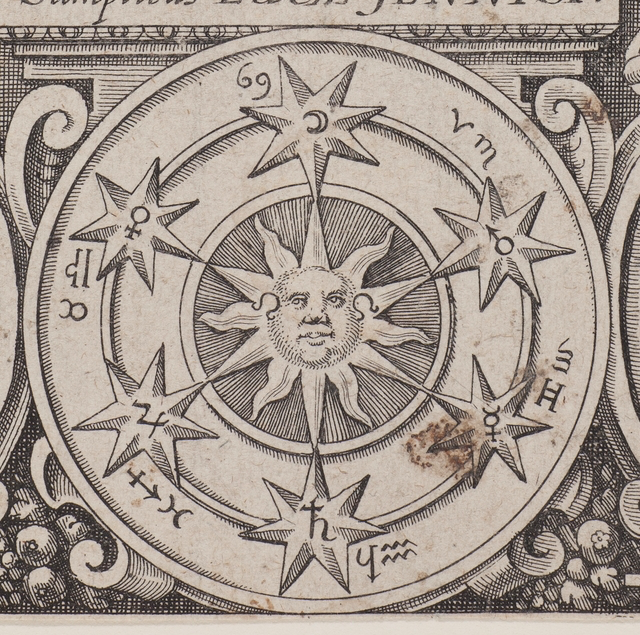

Here is a later example from Anatomia Auri (early 17th century) that I wanted to include because it combines medicine, astrology, cosmology, and alchemy. This astrological diagram focuses on Leo as the sun sign (notice the sign for Leo in the center by each of the sun’s cheeks) and, like earlier medieval drawings, shows the six other “planets” together with the sun:

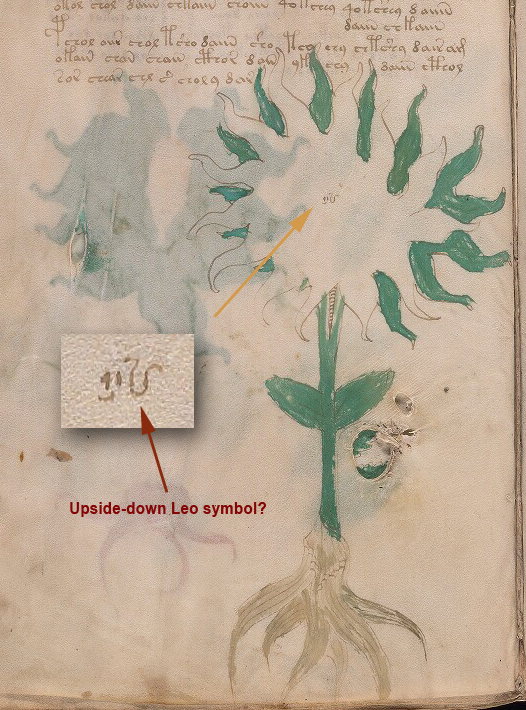

Why did I pick this one from the early 17th century rather than one from the 15th century? Because the Leo sign by the sun’s cheeks reminded me of this diagram on VMS 28v, which was discussed extensively by K. Gheuens and others on the Voynich.ninja forum due to the emblematic shape and the mysterious figures in the center.

I think the writing in the center could be interpreted in several different ways, possibly the way Gheuens suggested, but one of the ideas that crossed my mind was that the portion on the right might be an upside-down Leo symbol, similar to those on the cheeks of the sun-sign in the diagram above.

But getting back to Plant 46v, is it possible the flowers represent the earth on the left and seven “planets” on the right in the medieval earth-centric universe? Or is it something else?

In Kabbalah, the number one is the source, origin; seven is family, harmony, which might fit with an angel-root, but less so with a bird.

If the root is an angel, then perhaps the flowers on the right represent the angels of the seven churches, which are depicted here with each one holding a star:

Sometimes the seven stars of the seven churches are shown on one side, with the key of Solomon on the other:

Unfortunately, it’s hard to narrow down a specific analogy because symbols of 1 + 7 are rather common. It might be a mnemonic for stars, such as the Pleiades (the seven sisters) and their father Atlas. The Pleiades are roughly arranged in an arc, with their father to one side:

Or there might be a religious analogy…

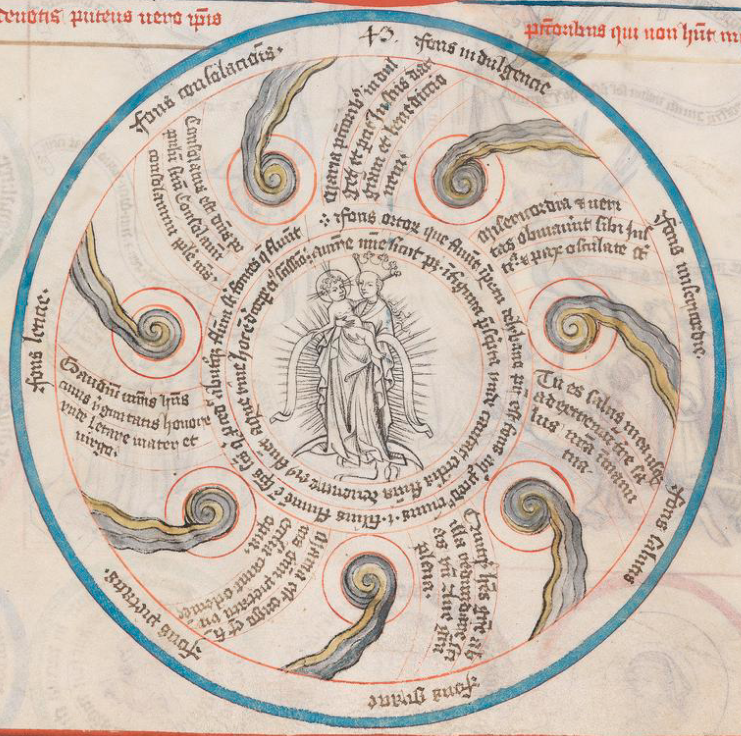

There is an image of the Virgin and child in the Pauper’s Bible that places the Virgin in the center of spiraling rings of water (the fountain or “font” analogy was adapted from water imagery in Pagan times).

You might wonder what this enigmatic drawing means (especially when one sees spiral images and a lot of water in the VMS, as well). It’s a mnemonic, in the Llullian tradition, representing a prayer that was widely included in Books of Hours. The fountains spiraling between Mary and the outer edge are invocations to the Virgin, representing her as the “fount” of mercy, grace, consolation, indulgence, etc.:

Thus, we see a focal point (Virgin and child) with seven comet-like “fonts” (funds, or fountains) in a spiral. It doesn’t look like the VMS plant, but the themes and elements are similar.

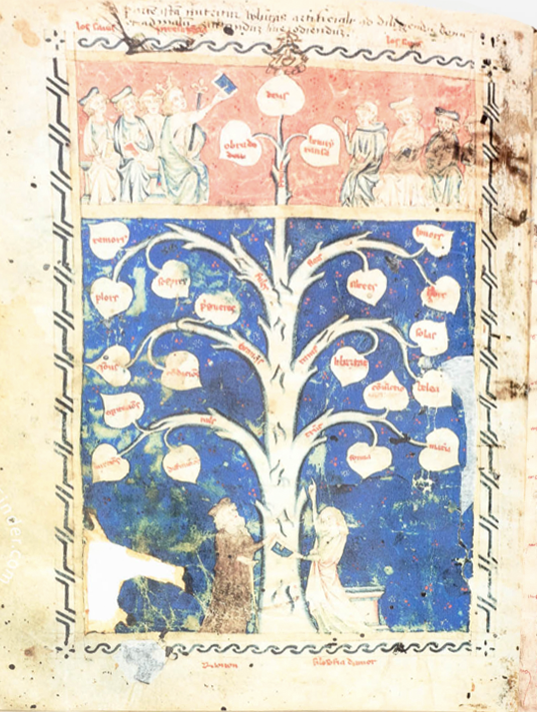

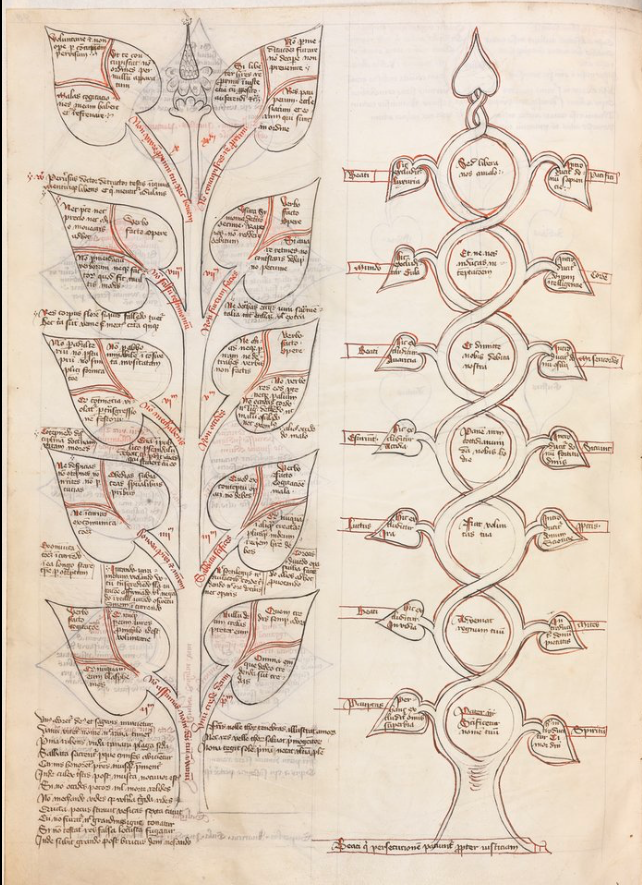

The Pauper’s Bible also has a large number of candlestick-like plant images, similar to those I mentioned in a previous post about The Desert of Religion and similar to those by Ramon Llull, as in this one enumerating key points of the philosophy of love:

Here are similar plant forms in the Pauper’s Bible that are used to express religious categorizations, concepts, and sometimes mnemonics:

Some of the VMS plants also have candelabra-like qualities, but they do not have labels on the leaves, so it’s difficult to know if they have a similar purpose.

In alchemical diagrams, an assumed relationship between astrology, the seven “planets”, plants, and candlesticks (a metaphor variously used for religion, heat, or light) and chemical processes (especially those of distillation) are frequently diagramed in a highly symbolic way, as in this example from Anatomia Auri:

Summary

I think two things are especially important to consider about VMS Plant 46v…

- The first is the apparently symbolic root, and the spiraling, broken-off flower stalks. They are more decorative or mnemonic than naturalistic. Viny plants are common in the borders of medieval manuscripts, but my research so far indicates this style (with the spiral stalks with a few broken off) was especially prevalent in English/Northern French manuscripts of the 13th to 15th centuries. But unlike the VMS drawing, the manuscript flower stalks were mostly decorations and a single plant did not usually occupy a full page.

- The second is to note that the drawing in the Pauper’s Bible is specifically mnemonic, in a way that was probably inspired by the works of Ramon Llull or one of his followers. It is designed to inform and to remind.

It’s easy to consider the root as symbolic, but perhaps the VMS flower is symbolic as well. Maybe the text that accompanies this specific drawing is not about plants. Maybe it is a description of a constellation (like Pleiades). Maybe the root is an eagle and the drawing is about alchemy. Or maybe Plant 46v represents a prayer and there is an angel in the root.

J.K. Petersen

Postscript: After posting a blog, I always notice a few hours later that I’ve forgotten something I intended to include.

This time, I left out the explanation for the oddities at the base of the plant stalk if the plant combines symbols from Christianity and alchemy. The eagle is a prevalent theme in alchemical diagrams and birds frequently represent ascension and the holy spirit in Christian imagery. So…

If 46v represents alchemical or Christian themes (or both), then the red shoulder and the odd round circle at the base of the stalk might be the blood of Christ (wine is a fermented product) and the “host” (the body of Christ as per Catholic tradition). In addition to possibly representing the “host”, the “o” might also double for the hole driven through Christ’s feet and hands at the crucifixion. I have sometimes seen this represented in medieval drawings as a simple “o”-shape.

Or perhaps it’s a symbolic representation of the philosopher’s stone (which was sometimes drawn in the claw of the alchemical eagle) or the pelican piercing its breast to feed its young (one of the common alchemical distillation jars was called a pelican jar due to the curved shape of the glass pipes that fed back into the main jar). In medieval illustrations, the pelican never looked like a real pelican, it was always drawn like a songbird or a small crane.

© Copyright J.K. Petersen Feb. 2020, All Rights Reserved

It seems certain that this plant is among the ones high in symbolism. I keep feeling “baptism of Jesus” with this plant but it’s probably wrong. If the root is the holy spirit, then this is among the options (there are not that many scenes where the holy spirit is routinely depicted).

And the flowers kind of look like cups used for pouring water, or perhaps the leaves as upturned vessels..

But from there on it’s shaky. An aspect of John the Baptist is his rough coat, which may be reflected in the leaves, but that doesn’t explain much about their shape. And he usually has a staff, but not the one with a crook. And then what’s with the amount of flowers…

The cut flower stems may just be there because there was actually no space to draw them, so that’s another complication.

JKP – nice image from the Liber Floridus. It reflects the Greek origin for the word ‘planet’, formed of two words meaning ‘wandering star’. Every literate person knew the term’s origin – it’s already in Isidore’s Etymologiae, the medieval eqivalent of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. (Ety. III.lxvii).

Isidore often illuminates the thinking behind medieval Latin imagery (especially to the 13thC). The first full English translation (published by Cambridge Uni Press in 2006) is now online as a pdf.

No help understanding the thinking behind the Voynich plants, though. 🙂