20 July 2020

Giovanni Fontana’s circle-line cipher is designed to be mnemonic without being too obvious about what the symbols represent. I’ve noticed this characteristic in several medieval and Renaissance ciphers, including the cipher of Hildegard von Bingen.

The Fontana Cipher

Johannes de Fontana (c. 1395–c. 1455) was a physician and engineer educated at Padua in the early 15th century. Fontana was interested in clockworks, and created entertaining devices, like clockwork-based skeletons, to showcase his engineering talent. But he is best known for Bellicorum instrumentorum (BSB Cod.icon. 242), an illustrated book of devices for warfare and sieges created in Venice in the 1420s.

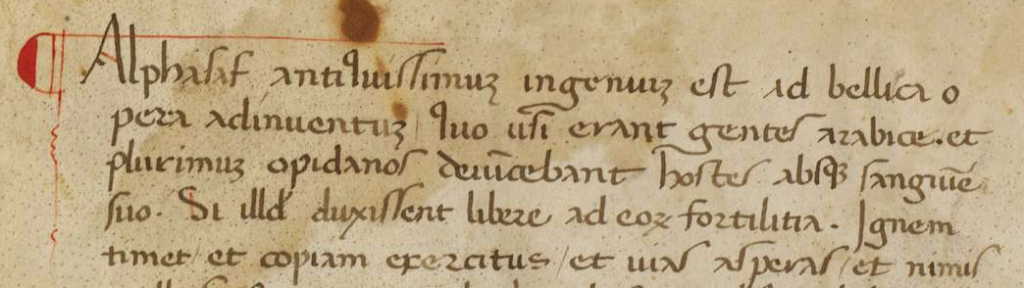

The introductory page of Bellicorum instrumentorum includes a paragraph of plaintext followed by ciphertext. Here is some of the plaintext:

Lombardy and northern Italy were part of the Holy Roman Empire in the 15th century. Venice managed to keep its independence through much of this period but was, of course, influenced by surrounding city-states. Italian culture is more evident in Fontana’s script than germanic culture. The final-ess (long-ess) is one of the clues. This was fairly common in Italy and much less so in Germany and France, where they preferred a B-shape or sigma-shape for final-ess. There is also a distinct lack of loops (a characteristic that was adapted by humanists all over Europe in the late 15th century and 16th century but was uncommon in Germany and France in the 15th century).

The “a” without a crossbar is another letter to note. This is a more traditional form of “a” that was uncommon in 15th-century Germany and France but used from time-to-time in Greek texts, early-medieval texts, and some of the Italian scripts. The raised “q” is unusual and Fontana did not always write it this way in earlier texts.

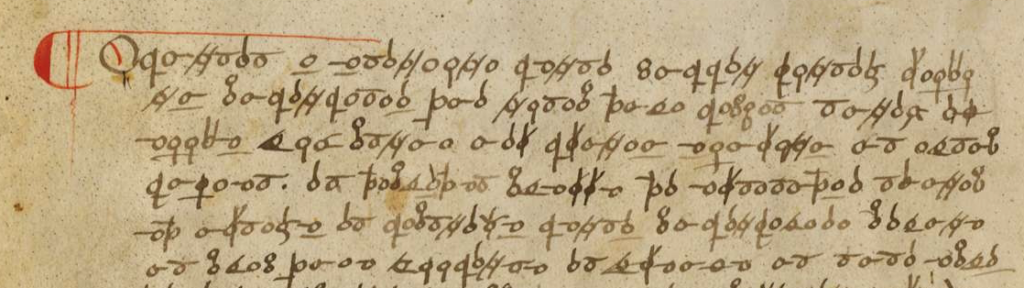

Below the plaintext is a block of ciphertext:

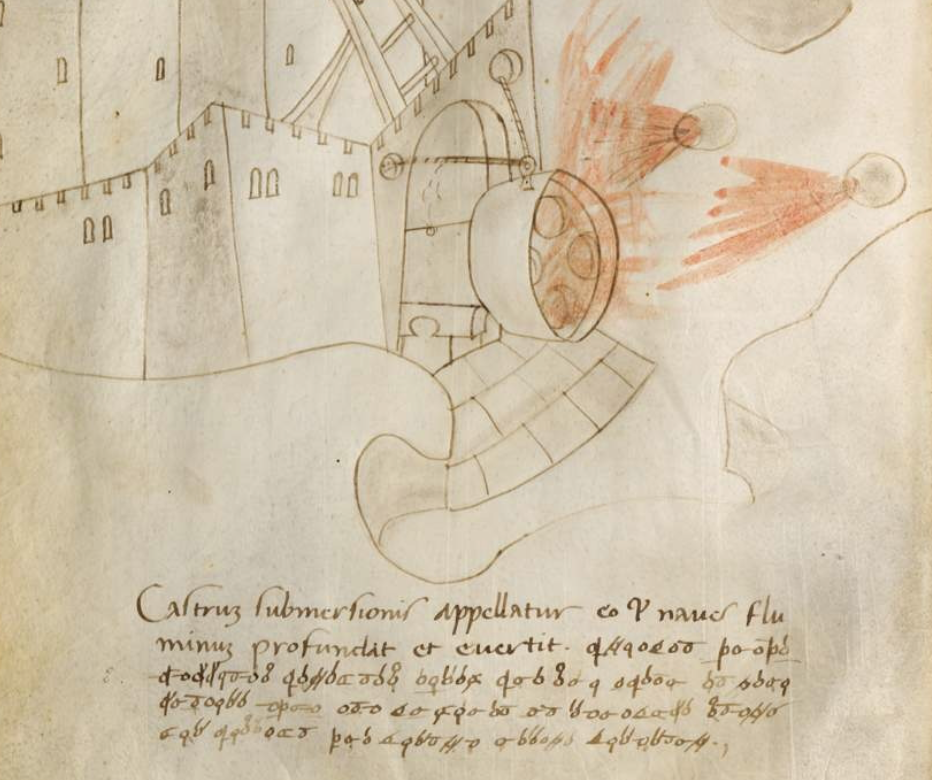

Most of the folios include a drawing, a block of plaintext, and a block of ciphertext:

The drawings are not professional-level, but they are reasonably clear and instructive, like the VMS drawings. The main difference is that the Fontana drawings show a better understanding of three-dimensional mechanics than the VMS (the weakness in three-dimensional thinking is especially apparent in the muddled way VMS human joints are drawn).

The Fontana Cipher Characters

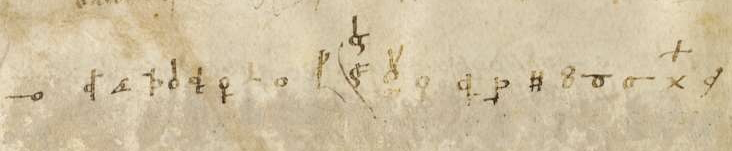

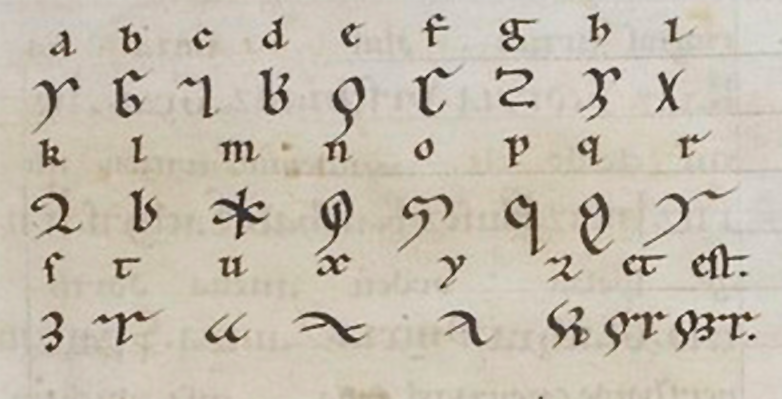

Someone has added the following alphabet to a foreleaf of Bellicorum instrumentorum, but you don’t need it to decode this cipher. Fontana designed his cipher to be easy to read, thus making it easy to decipher:

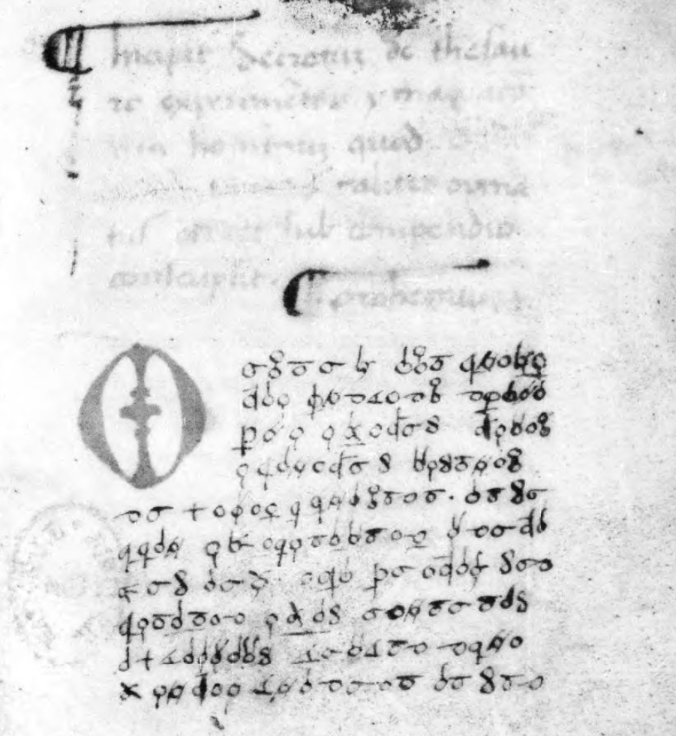

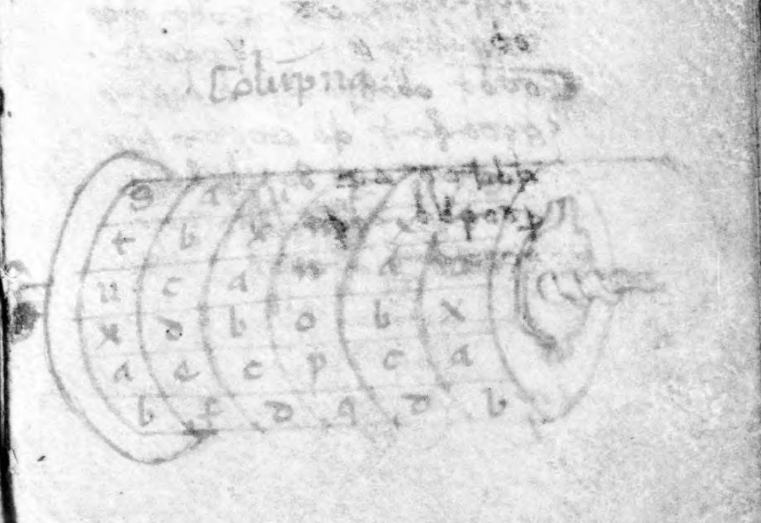

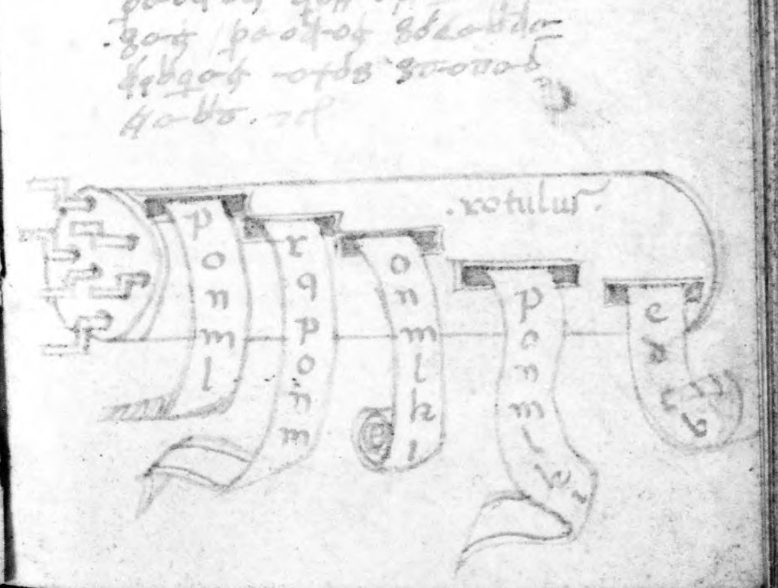

Before I break down the alphabet, I’d like to point out another book by Fontana, called Secretum de thesauro experimentorum ymaginationis hominum (BNF NAL 635, c. 1430). Like Bellicorum, this includes a significant amount of ciphertext and some interesting rotary text mechanisms:

The manuscript describes various kinds of memory and mnemonic devices and Fontana’s interest in these subjects sheds some light on the design of his cipher.

The Rationale Behind the Fontana Cipher

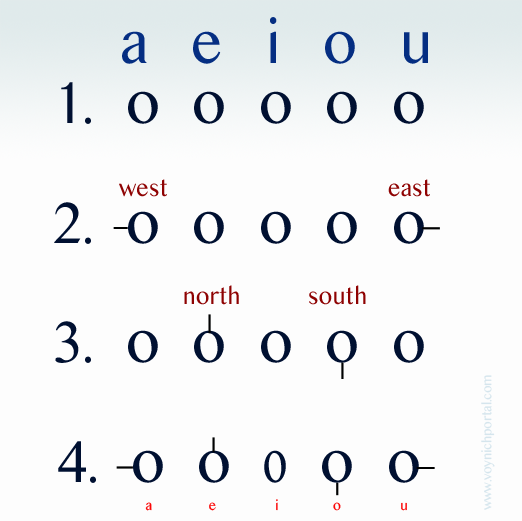

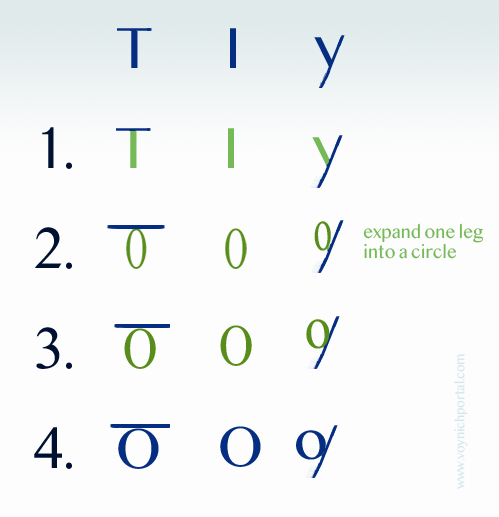

Start with a basic concept—circles and tickmarks.

- Line up the vowels with a circle to represent each one.

- Starting with the outermost circles, add tickmarks facing west and east.

- Now go to the “e” and “o” circles and add tickmarks facing north and south.

- There are 5 vowels and only 4 cardinal directions, so leave the “i” as it is but you can imagine the circle being squished in from the sides until it resembles “i” (this will also help with remembering another letter). You can draw it round, you just have to think of it squished to remember it’s the letter “i”.

Now you have 5 vowels.

How can circles and tickmarks be used to create consonants while still keeping the cipher reasonably mnemonic? Quite often in medieval ciphers (including the cipher of Hildegard von Bingen), some of the cipher shapes are formed by mirroring.

In Hildegard’s lingua ignota, the r, b, and h are drawn almost in the normal way except an extra tickmark has been added to b and h. The letter “u” is normal for her time period, as well (the double-cee sometimes also stands for “a” in early-medieval texts). But the “d” and “p” have been mirrored in the horizontal direction and “y” is mirrored in the vertical direction:

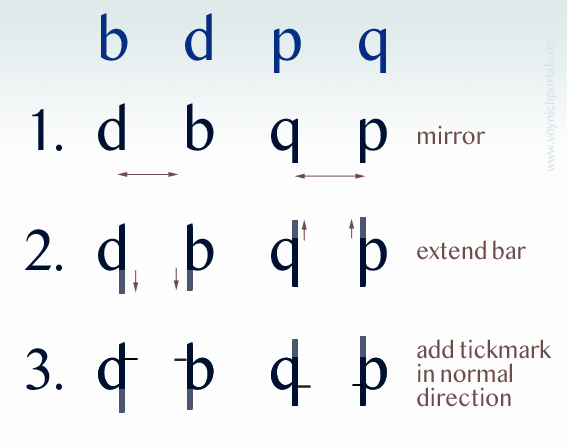

Fontana used mirroring, as well, in a more methodical way than Hildegard.

- Take the letters b, d, p, and q (which are morphologically similar) and mirror them in the horizontal direction.

- Extend the straight strokes (otherwise the identity of the letter is a little too obvious).

- Add a tickmark pointing in the direction the letter would normally face, and further place it up for b and d, down for p and q (the normal direction for the ascender or descender).

Creating a mnemonic “s” is easy. Close the loops. It can be written both vertical and horizontal and is still easy to remember because it is the only character with two loops. The “t” is also easy. Remember that the “i” is a simple loop and imagine it squished. Now add a crossbar on top and you have a mnemonic “t”. In fact, some of the other consonants, like y and z also substitute the circle for a stroke.

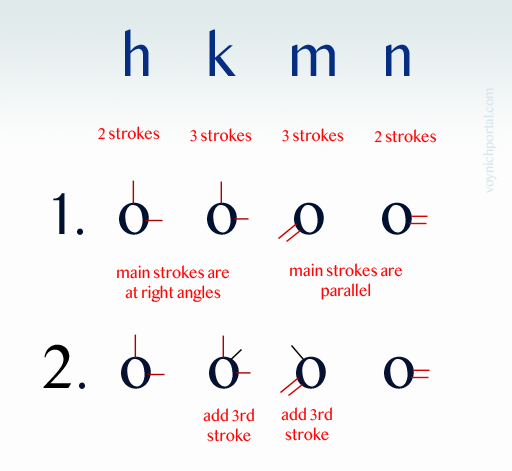

After a while, you run out of the simple shapes, so Fontana used a different way to remember h, k, m, and n. Instead of mirroring, these letters are based on strokes. The letter “h” has two main strokes, so the cipher character has a circle with two strokes up and right. The “k” also has two strokes up and right, but the letter “k” has a third angled stroke, so this is added as well:

The letters “m” and “n” work the same way. The “m” has three strokes, the “n” has two, and this is how many are attached to the circle. The direction doesn’t even matter since h and k are at right angles, with one stroke mimicking the ascender. The m and n are parallel and thus easy to distinguish from h and k.

This is quite clever. It might be worth repeating… since the parallel and perpendicular lines are distinguishable by their angle, the direction doesn’t matter and Fontana does sometimes vary the direction. This concept could be used to design a new cipher that was more difficult to read, by varying shapes so they appear to be different when, in fact, they are not. That was not Fontana’s intention with this cipher, but it presents some intriguing possibilities.

That’s most of the alphabet. The “f” is mirrored in the vertical direction and since all the letters are circles and lines, a circle is added in the crook.

You might think that Fontana used a Venus symbol, but the resemblance is coincidental. If you move the ascender of the “g” to the center and add a tick, in the same pattern as the other characters, it is recognizable as a “g”. If you make a mouth shape with your left hand and imagine you are holding a marble, it creates the ciphershape “c”.

At the end of the alphabet, we have x, y and z. Draw a cross for x and put a circle in the crook. This is another construction in which direction doesn’t matter. As long as it begins with a cross, you could recognize it no matter which direction it’s turned (I’m going to keep emphasizing this, since a cipher based on these concepts has flexibility that linguistic alphabets don’t). Since crosses are often substituted for X, this is easy to remember.

Draw an angled line for y and z (both of which have angled strokes) and put a circle on the side that needs a missing stroke and use an extra connector to distinguish z from y.

There are only two letters that are difficult to categorize, and that is “l” and “r”. Maybe readers can figure out the motivation behind them.

Overall, the cipher is systematic and mnemonic.

Summary

Many ciphers are intended to conceal and the desire for hard-to-crack systems increased in the 15th century. More sophisticated ciphers (by medieval standards) included one-to-many relationships, revolving keys, nulls, and glossaries. Numeric ciphers became more prevalent as well. Soon a whole science of cryptology began to develop, one that is still evolving today. One-to-one substitution was basically obsolete by the 16th century.

So why was Fontana’s cipher so easy to decipher and to learn? I think that’s exactly what he intended. He had an interest in mnemonic systems in general and his cipher demonstrates several memory-jogging techniques that enabled him to write entire tracts in cipher characters.

Now you can read Fontana’s books. Just remember that “u” and “v” were interchangeable in the Middle Ages. Here’s a simple word to get you started.

Also… I noticed, as I was paging through Secretum, that Fontana broke words across lines without line-continuation marks and that he did use some light abbreviation, but he included abbreviation marks, so it’s not particularly troublesome.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright July 2020 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved