24 October 2020

Mandrake is one of the best-known plants in medieval herbals. The root is roughly humanoid, and medieval entrepreneurs sometimes carved it to make it more overtly human. Folklore said it was dangerous to dig up the root. The plant would shriek and hearing it could kill you, so harvesters were counseled to use a dog on a leash to dig it up.

The Mandrake in Medieval Herbals

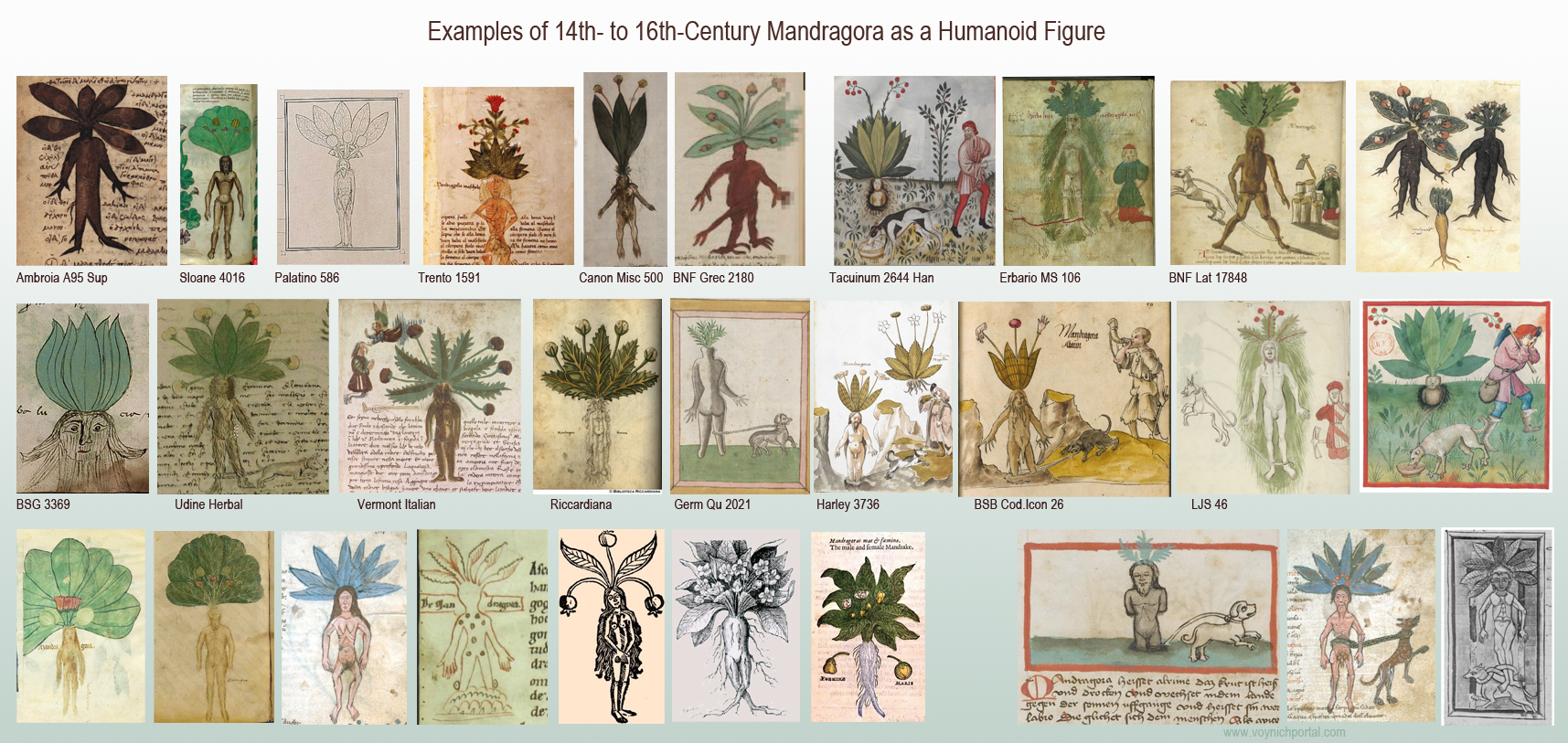

Many medieval herbals included the mandrake, from countries like Italy, France, England, Germany, Greece, the Middle East, and others.

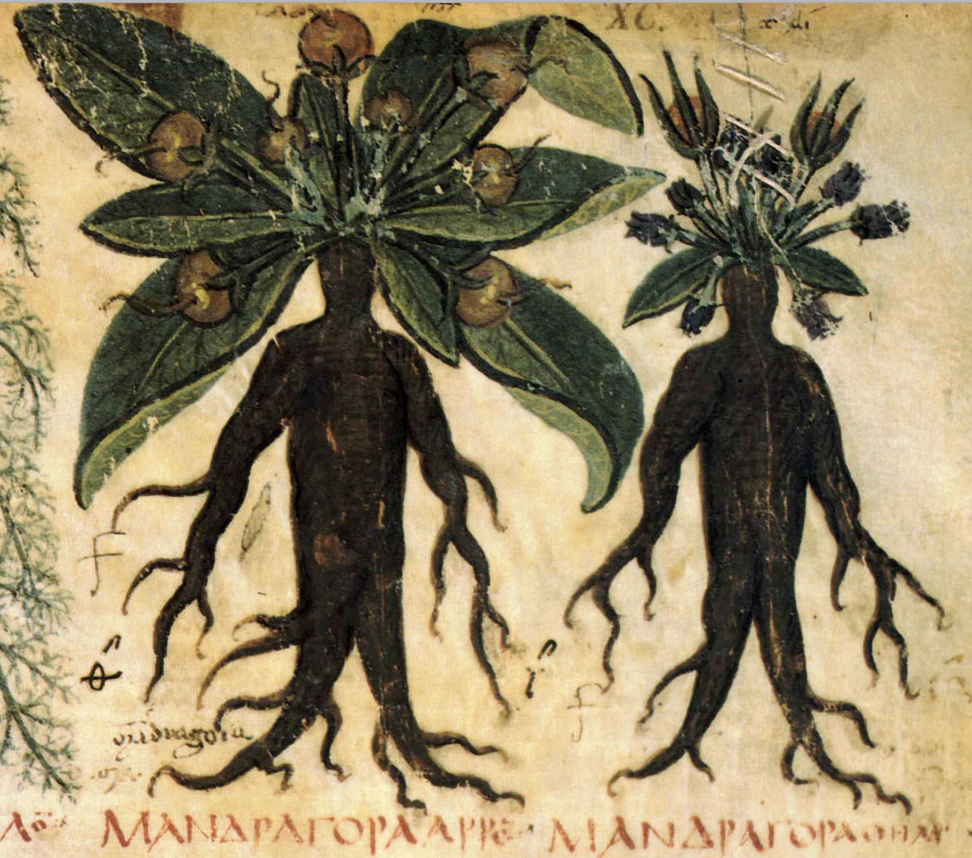

Sometimes only one plant is shown, sometimes two versions: “masculine” and “feminine”, as in these Arabic manuscripts:

The male/female dichotomy goes back to the Dioscorides. In this early copy, the faces are not explicitly drawn, but the roots are distinctly humanoid. A dog is not included in the image, but is mentioned in the text:

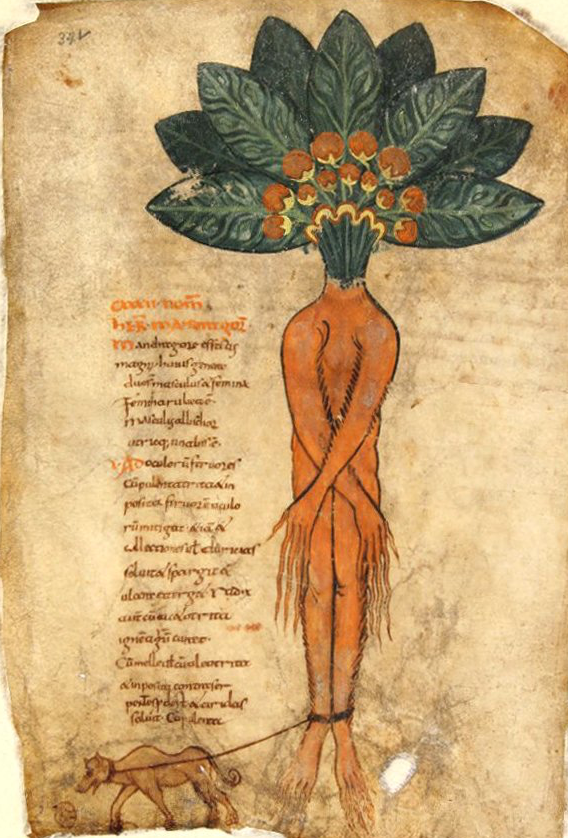

The humanoid root appears in early copies of Pseudo-Apuleis with a dog, but still does not have a humanoid face:

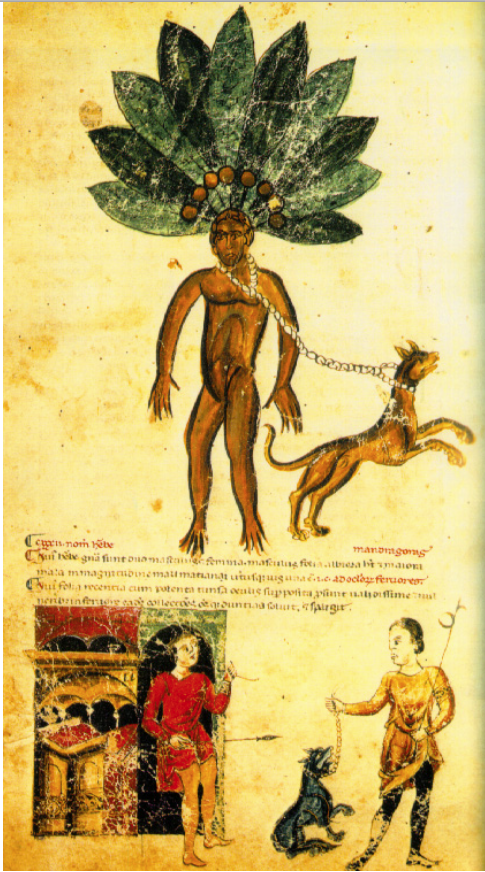

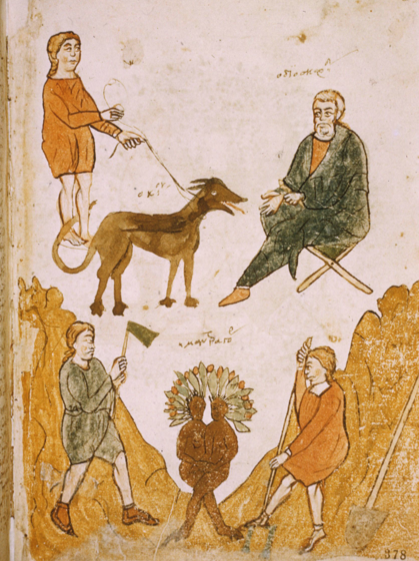

The anthropomorphic Mandrake was especially popular in the 12th to 15th centuries. This one, from 12th-century England, includes the dog pulling out the plant while two figures approach with hooks or spears:

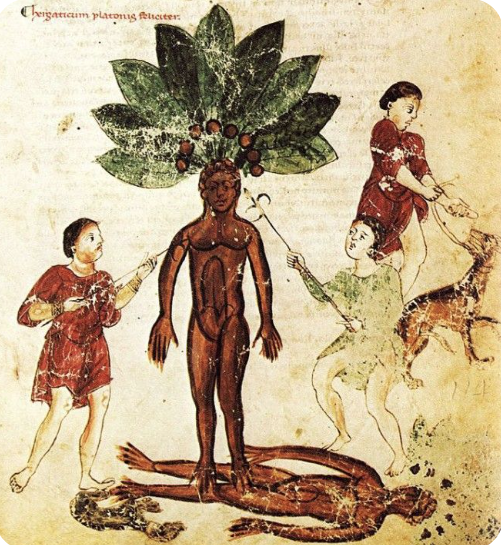

This 13th century example is the same basic theme, with the dog, and figures with spears, but the narrative is broken up into a series of panels:

On the facing folio, the dog has done its job and two figures poke the root with hooked spears, but it is different from most depictions of mandrake in that a second figure is under the feet of the standing mandrake. The shadow under the character on the left is very doglike.

This version is the same general idea, but the spears are replaced by more familiar tools, and the male and female versions are shown as conjoined twins:

The dog is not always included. Here are a number of examples that emphasize the humanoid form both sans and with the dog:

Most mandrake drawings include berries. Some have smooth leaf margins, others are serrate. In real life, the margins are ruffled and irregularly serrate.

In the 16th century, the humanoid form was gradually superseded by naturalistic representations.

Is Mandrake in the VMS?

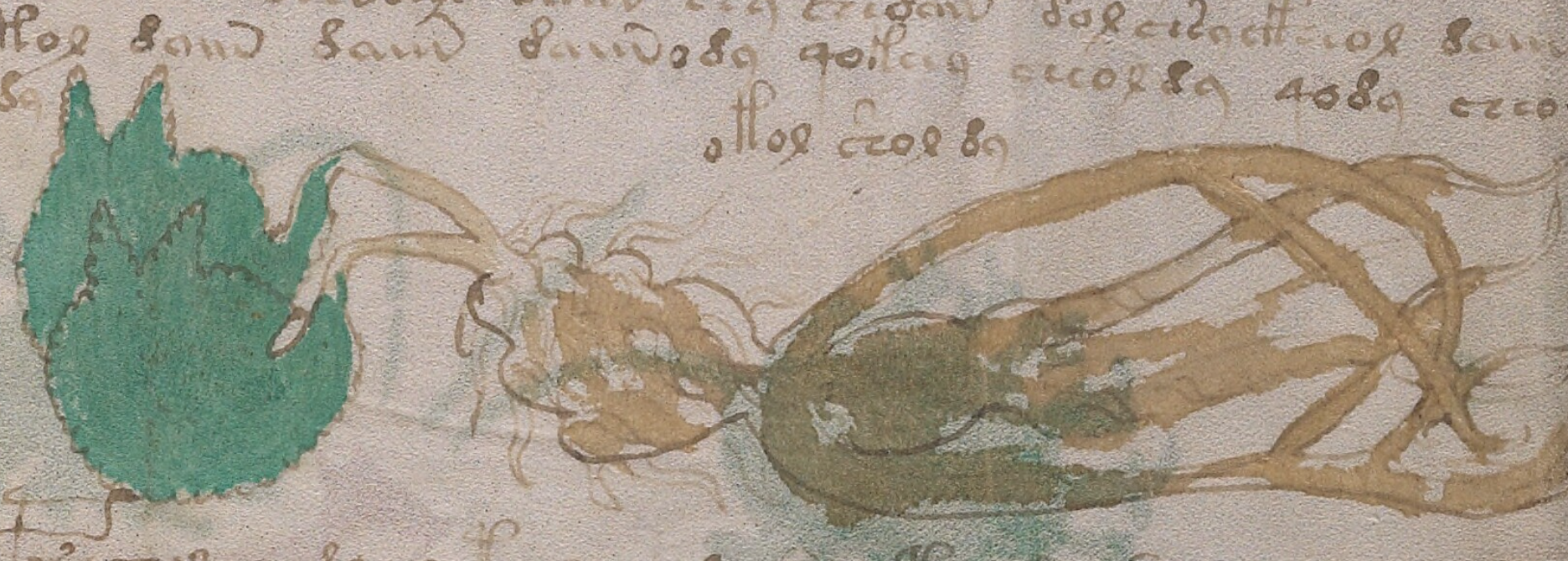

The Voynich Manuscript has a large number of plants in the “big plant drawings” section, and yet there’s nothing that overtly resembles Mandrake. Some have suggested that f33r might be mandrake, but I think there are better identifications for 33r.

A better possibility is f25v, but the root is not humanoid, the leaves are not ruffled or serrate, and they have been carefully drawn with parallel veins, more similar to Plantago or Dracaena. The little dragon is not typical for mandrake plants and I have a few things to say about the critter in another blog.

The VMS is incomplete, so if Mandrake was included, maybe it was separated from other folios. Or… perhaps it is in the section with the small plant drawings…

Artfully Subtle

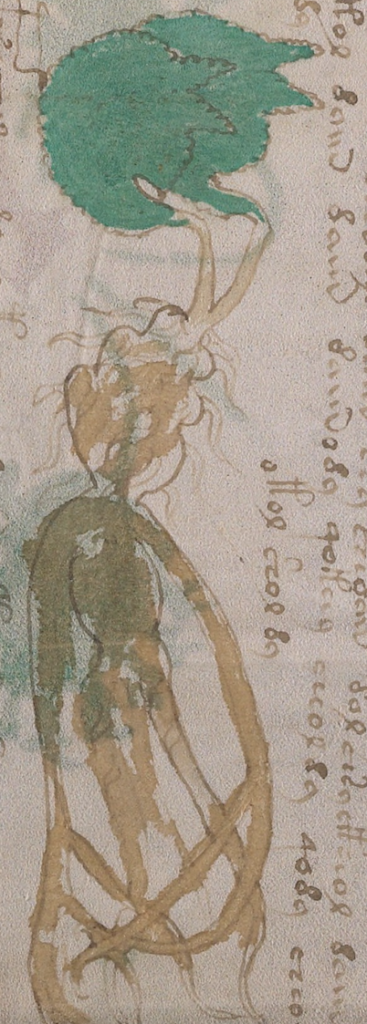

I’ve been intending for years to write about the small-plants section, but it’s a large number of plants, my notes have turned into a dauntingly huge pile, and it’s hard to find time to write it up properly. But I’m beginning to think I should mention this particular plant because I’ve believed for a long time that it is mandrake, and that it is partly mnemonic:

If you turn your head sideways, you can see the human figure, or rather a fairly naturalistic root with humanoid overtones. The head has little rootlets that look like hair, the shoulders have long root-like arms. There’s a rounded body and rootlike legs. To the left, coming out of the head, are two leaves with serrated margins. I believe the leaves are shaped to represent the heads of dogs, with ears facing right and the muzzle vaguely suggested.

Why two dog heads? Maybe the intention was to imply male and female plants without being too obvious about it.

Mandrake is toxic. Maybe the prone posture represents something that can make you ill.

If this is Mandrake, it gives us insight into the drawing style and thought processes of the VMS designer. The important elements are there, but nothing is completely traditional or overt. The figure is sideways, thus making it less noticeably humanoid. The dogs are not drawn separately, but included as a mnemonic in the leaves. It’s subtle, whimsical, clever, and irresistibly cheeky.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright October 2020 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

I think there is more going on, but the plant could certainly be influenced by mandrake. I’d say especially a more “rooty” version like in the Dioscorides. The small-plants section certainly deserves to be written about more often 🙂

I’m not sure there is direct influence from medieval herbals.

Perhaps it was someone who knew plants, who managed a garden, who then had a chance to glance through a regular herbal (oak and ivy) and perhaps one of the so-called “herbals of the alchemists” (with symbolic and mnemonic roots), someone who said, “That’s a cool idea,” and then went home to create the VMS based on his or her personal knowledge of plants (and medieval understanding of mnemonics)… without the opportunity to copy directly (books were precious commodities that most people couldn’t afford).

There is quite a bit of naturalistic detail in the VMS drawings, details one doesn’t usually find in plant drawings of the early 15th century, details that might be included if a harvested plant were next to the illustrator.

The leaves certainly appear to be symbolic or mnemonic, and yet even though the root has a humanoid form, it is more similar to a real mandrake root than it is to traditional drawings.

This is also true of the plant usually called the “water lily”. The rhizome is more similar to a real plant than to traditional drawings.

I enjoyed reading this interpretation of a “small plant” drawing. My father studied the Voynich manuscript for more than forty years. He once showed me a word he’d translated as “dill.” I told him that the drawing on the page quite resembled a dill plant. He knew nothing of herbs and gardening, and had little interest in the illustrations, having spent his life primarily devoted to linguistics and translation. He felt in some places, the very small drawings were used to mark transitions in thought, as in paragraphs (i.e. use of flowers along margins). There were often huge copies of Voynich pages spread across my father’s desk at home, and I remain fascinated by the enigmatic drawings.