11 February 2021

I have to make this quick. My time for blogging is very limited (and I have many mostly-finished blogs I need to get posted). But I thought this quirk in some medieval zodiacs might be interesting to Voynich researchers.

Mislabeled or Misunderstood

In a cruise through eBay a couple of years ago I noticed that many small sculptures, pieces of jewelry, and designs on ceramics that were based on animals were mislabeled. Foxes labeled as mice, hedgehogs labeled as boars, deer labeled as foxes. These were not occasional errors, they were common. Apparently, some people don’t recognize animals, especially if they are small.

I’ve already posted a blog on how unrealistic medieval animal drawings can be, but sometimes this is because the animal was unknown. For example, unicorns sometimes resembled a cross between a goat and a rhino. Tigers were sometimes drawn as stripy horses. Elephants were sometimes cowlike animals with long noses.

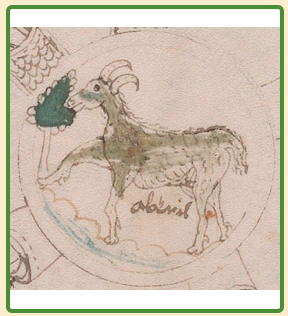

I have also seen marginal drawings of goats labeled as sheep (and sometimes vice-versa). The VMS pic where one would expect a sheep, in the slot usually assigned to Aries, does have fairly curvy horns but otherwise is quite goat-like:

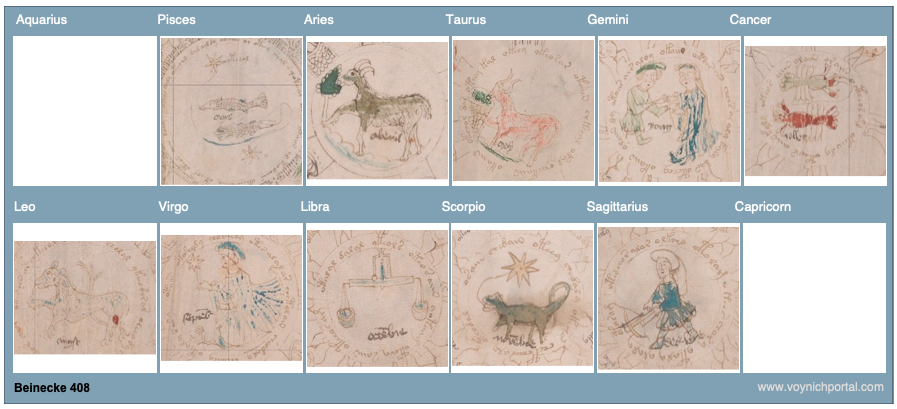

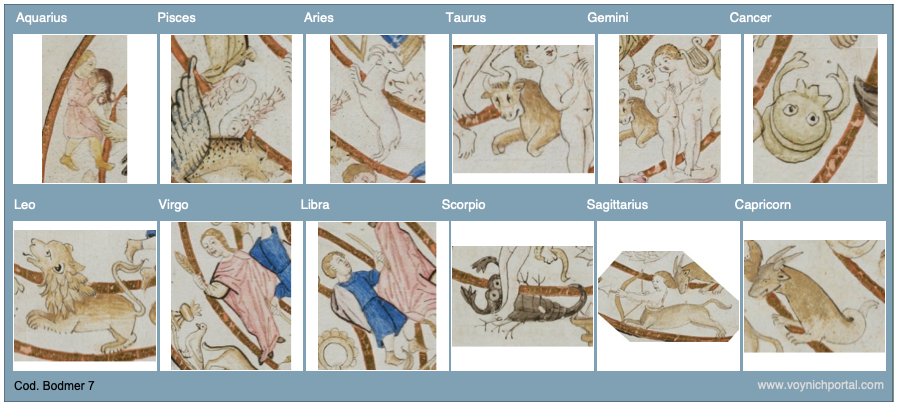

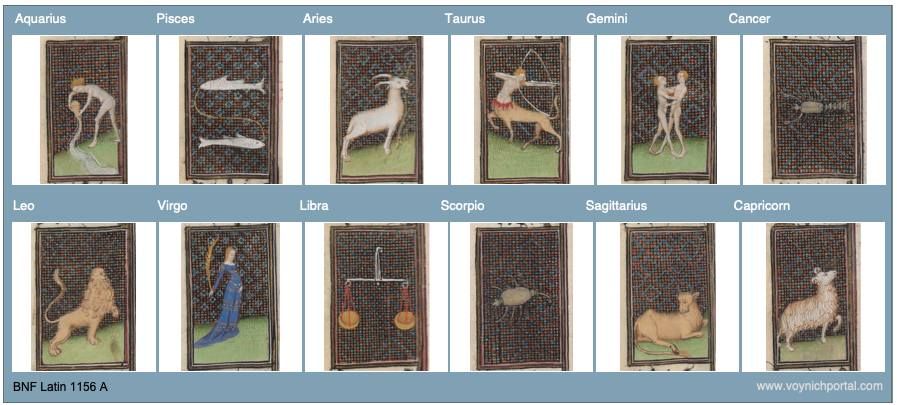

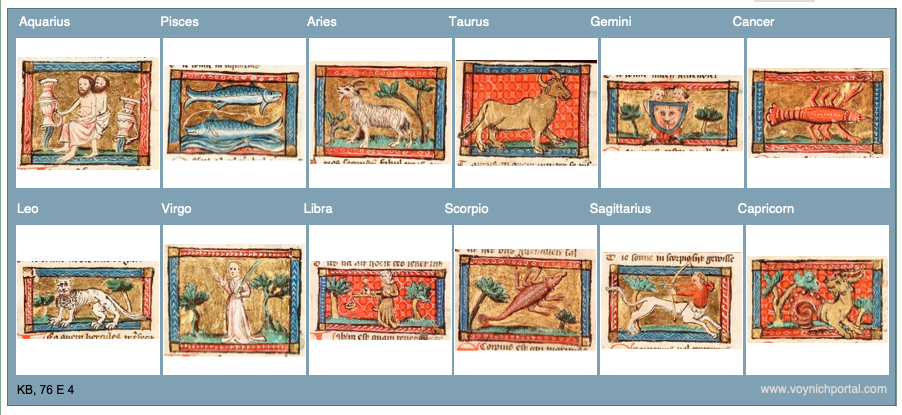

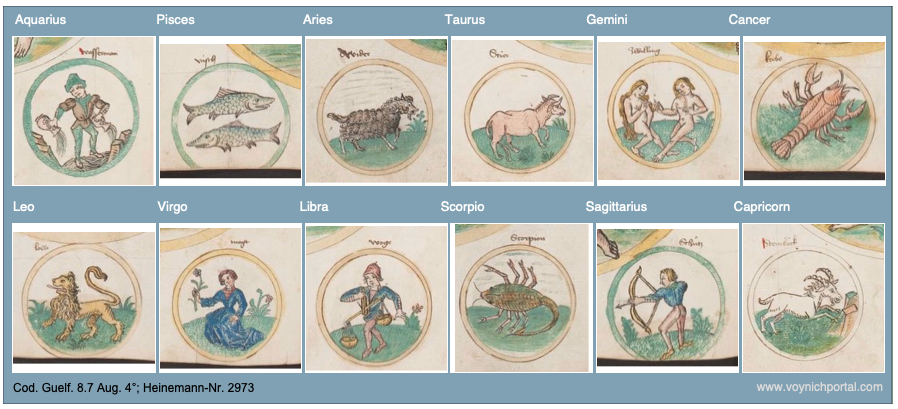

Does this happen in other medieval zodiacs? Yes, sometimes. Here are some examples.

Goat-Like Aries or Misplaced Figures

In the first example, extracted from a wheel illustration, the constellation Aries is somewhat goatlike, especially considering that medieval sheep were often drawn with long tails. However, it can still be distinguished from the goat by having slightly more curved horns:

The following drawings are a bit degraded, so it’s hard to see clearly, but the goat and ram have been transposed. The drawing in Aries has long horns and a short, upturned tail (goat-like), and the one in Capricorn has shorter, curved horns and a longer down-turned tail:

In this example, the figures are out of order. The illustrator mistakenly drew Capricorn (goat) and Sagittarius (centaur) in the months for Aries (ram) and Taurus (bull).

In the next example, Aries has a goatlike beard and the traditional goat-fish has been used for Capricorn:

In this example, Aries has sheep-like wool combined with a goat-like tail and beard:

Sometimes the drawings are so similar, it’s difficult to tell the sheep from the goat. In this case the bodies are almost the same (Aries is slightly thicker, but not much). The main difference is the curl of the horns:

Summary

In general, in medieval zodiacs, Aries is depicted with curly horns and a puffy or long tail (usually pointing down), Capricorn usually has a shorter tail, sometimes upturned, with straighter horns and often a beard.

It doesn’t happen often, but Aries is sometimes drawn like a goat, and Capricorn is occasionally transposed with Aries. The VMS goat-like sheep in the Aries slot is somewhat unusual, but it’s not unprecedented, so it’s difficult to know if the deviation is lack of experience, a mistake, or a deliberate choice.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright February 2021 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

I wonder what happened with the aquarius in the KB MS. Gemini hybrid? Given the VM lack of aquarius, I am not as familiar with this sign to begin with.

Yes, good observation.

Most of the zodiac figures in KB 76 E 4 follow traditional themes, but it’s unusual for Aquarius to have two figures. Two jugs is not unusual, but two figures is different.

I would have to check my files to be sure, but I don’t remember other Aquarius figures being drawn this way.

Koen, it suddenly occurred to me why Aquarius in the KB manuscript has the Janus-style head.

Sometimes the month’s labor for January has a two-headed figure. The illustrator may have combined (or confused) the January zodiac with the January labor.

JKP – the assignments of labors to their months is (as I once explained in detail) changes according to Latitude within manuscripts of Latin Europe and can be helpful pointer to provenance.

It makes sense when you think about it – obviously you can’t do the same things in Norway or Scotland, in February, than you can in southern France or Sicily. So while the month’s constellation was the same, the imagery adapts the labor to what is actually feasible in a given region.

When I hunted for examples of goats used for Aries, I found it had historical and political background, as well as geographic reasons, but since I covered all this aspect of the research when writing it up, I won’t risk boring you by repeating it. I found it especially interesting that the two Aries goats (first noted by a contributer to the first Voynich mailing list) omit the billy’s beard – and one tends to find goats drawn with such nicely formed jaws, and no beard, in the eastern Mediterranean. But again – I talked about all that before.

What I meant to say was that your examples would be even more interesting if you labelled them with details of the manuscripts from which they come. It helps other researchers form a clearer idea of geographic and chronological distributions.

Thanks

D.N. O’Donovan: “What I meant to say was that your examples would be even more interesting if you labelled them with details of the manuscripts from which they come.”

D.N., you constantly rebuke me for not including shelf marks, but every example I posted above includes a shelf mark.

The fact that month’s labors would change with geography seems obvious to me, but we also have to consider that someone in the south might make a faithful copy of a manuscript originally designed in the north, in which case, there might be a mismatch between the creation location and the tasks.

I have also noticed that the intended audience of a manuscript has some influence. Some Months’ Labors series indicate the work that has to be done each month, while others (notably some of the French ones) include times of leisure (for the nobility) while only suggesting (or ignoring) the work done by others during that time.