I have written numerous times about Voynich “4o”, on my blog, on the forum, in comments on other blogs, but I have a feeling it needs to be done again because there may be misunderstandings about how the “4” glyph relates to others in Voynichese and to ciphers in general.

I’ve often seen Voynich researchers say that “o” usually follows “4” and, from a visual point of view that may be true but, in terms of understanding the VMS “4” character, it would be wiser to say that “o-tokens” are frequently prefaced by “4”. The idea that the “4” and the “o” are inextricably linked is not completely true and the idea that they are a unit, in essence one character, is not supported by evidence.

Does 4o Relate to Diplomatic Ciphers?

The diplomatic cryptography systems documented by Tranchedino are based on many-to-one and one-to-many substitution schemes, which means there are sometimes hundreds of characters per cipher system. The cipher on folio 1r of Diplomatsche Geheimschriften packs almost 340 glyphs into a single cipher system.

Think about that… 340 shape-combinations for a single cipher. This is in stark contrast to the VMS, which renders most of the text with 22 glyphs.

Diplomatic ciphers also coded names and common words into symbols and cipher pairs. For example, the cipher glyph for “Papa” is the Latin abbreviation symbol v + “-is”.

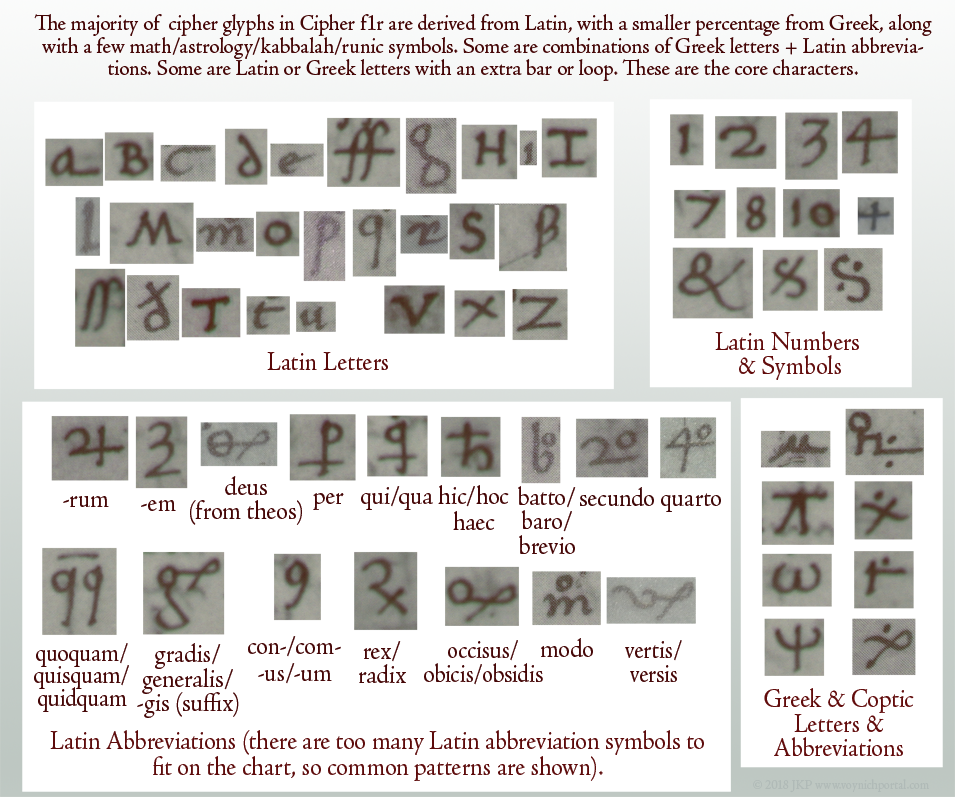

This creates a huge demand for shapes, but many were based on a core set. Here are the most familiar characters used to create the cipher system on f1r of Tranchedino’s collection:

It’s clear that Cipher 1r relies heavily on Latin letters, numbers, and abbreviations. Arabic and Hebrew letters (other than kabbalistic loops and lines) are conspicuously absent.

The straight and wiggly lines above some of the letters (not shown) are Latin macrons (the medieval version of the apostrophe). In fact, there are dozens of Latin abbreviations, too many to include on the chart. There is also a smaller percentage of Greek letters and abbreviations, and math/astrology/kabbalah/runic symbols. Sometimes Greek letters are combined with Latin endings (e.g., Greek letter theta + Latin “is” abbreviation), which is not uncommon in Latin texts.

The cryptographers created many new shapes by adding an extra line to a common shape. Or they would remove a stem or add a loop, as in these examples:

There are very few shapes that are pure inventions. Most are common shapes, combinations of common shapes, or common shapes altered in regular ways, as in the above examples.

There are very few shapes that are pure inventions. Most are common shapes, combinations of common shapes, or common shapes altered in regular ways, as in the above examples.

So what inspired “4o” in diplomatic ciphers?

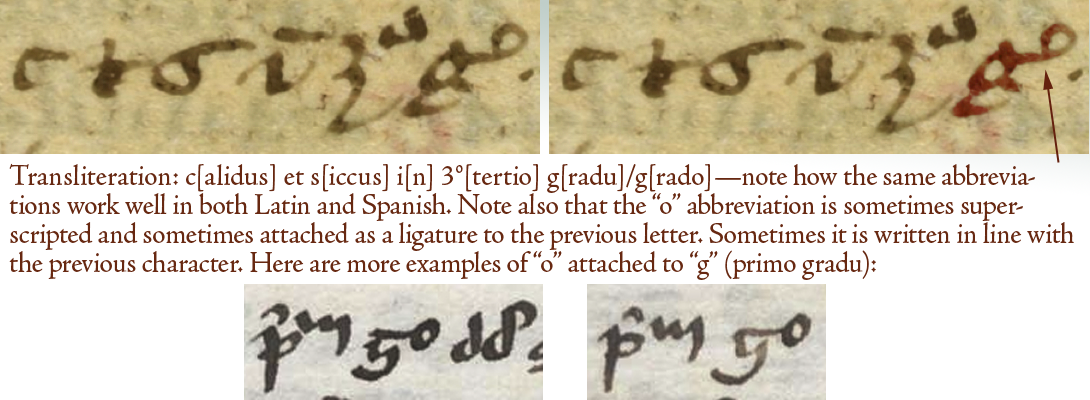

In Latin, it is a common convention to add a small “o” to represent words that end in “o” like “modo”, “quomodo”, “quo”, “libro”, “ergo”, “tertio”, or “quarto”. Latin abbreviations are also applied to homonyms, so buy cheap Gabapentin online go can also represent “gradu”. Thus, we have mo or mo (modo), go or go (ergo/gradu), quo or qo (quo), and 4o or 4o (quarto), etc., several of which are included in Cipher 1r.

One of the more common of these abbreviations, often seen in herbal manuscripts, is “gradu” (grade/degree). It is typically written like the character highlighted below-right.

This is highly abbreviated Latin, so I have transliterated it to make the ordinal number (tertio) and the “o” abbreviation (gradu) easier to see. Both are abbreviated in the same way. Note that the “g” has the “o” attached:

The abbreviation “o” can be placed in almost any position and still mean the same thing. It can be directly above the letter, superscripted to the right of the letter, or attached directly to the letter.

Diplomatic Cipher 1r includes abbreviations for “modo”, “secundo”, and “quarto” (4o). The 4o is not an invented shape. It is used to represent ordinal numbers in several languages.

Related Abbreviations

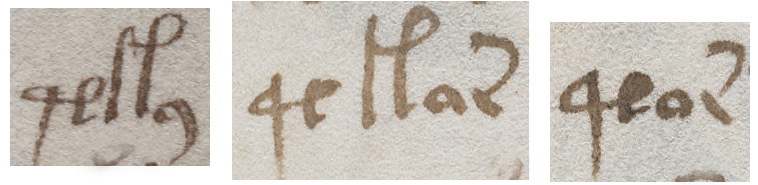

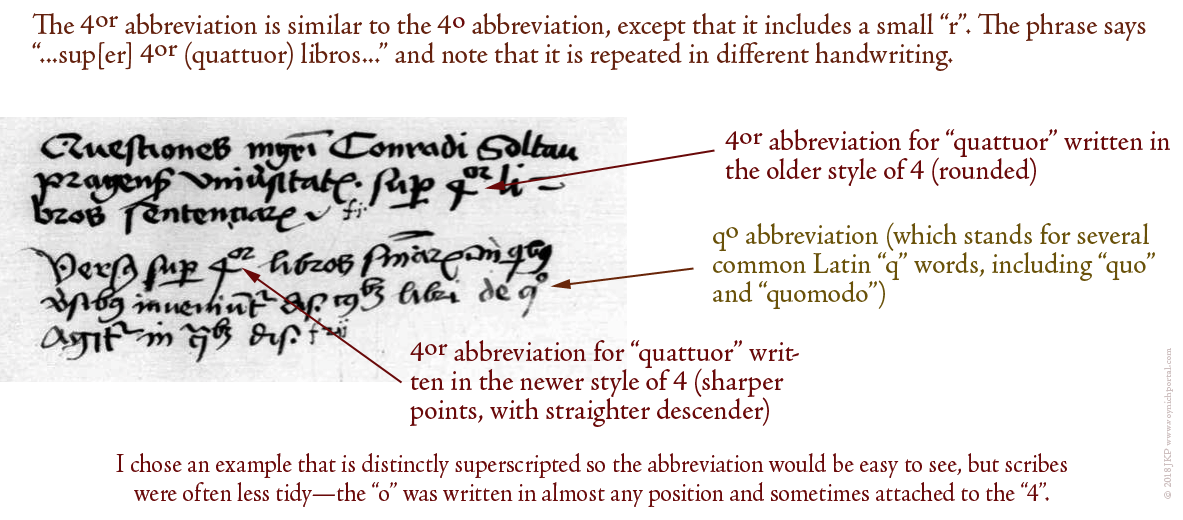

Here is an example of a related abbreviation (4or ) so you can see that this is a generalizable pattern. Even if you’ve never seen it before, you can figure out what it means because it is constructed in the same manner as mo, go, and 4o:

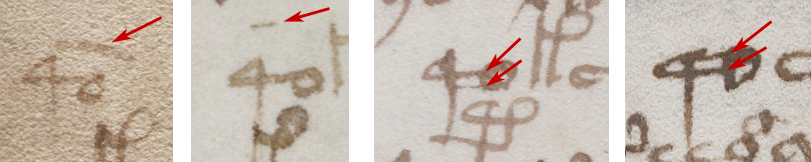

I chose this example for a second reason… it is written by two different scribes, one using the older form of “4”, the second using the newer. Note the “soft-4” (the older form) and the “sharp-4” (the one that became popular by the mid-15th century). In the VMS we see the “4” character written both these ways, and there is also an in-between shape that resembles “q” more than “4”:

This variability could have a number of explanations… different scribes, subtly different glyphs (possibly with different meanings), or scribes from the early 15th century who were transitioning to the newer form (I’ve seen foliation where the scribe changed the older rounded 4 to the newer one and then continued the rest of the numbers with the newer form, as though someone had told him to update the style).

Here is an example of how “quarto” was abbreviated in the 14th century, with the rounder form of “4” that was popular at the time:

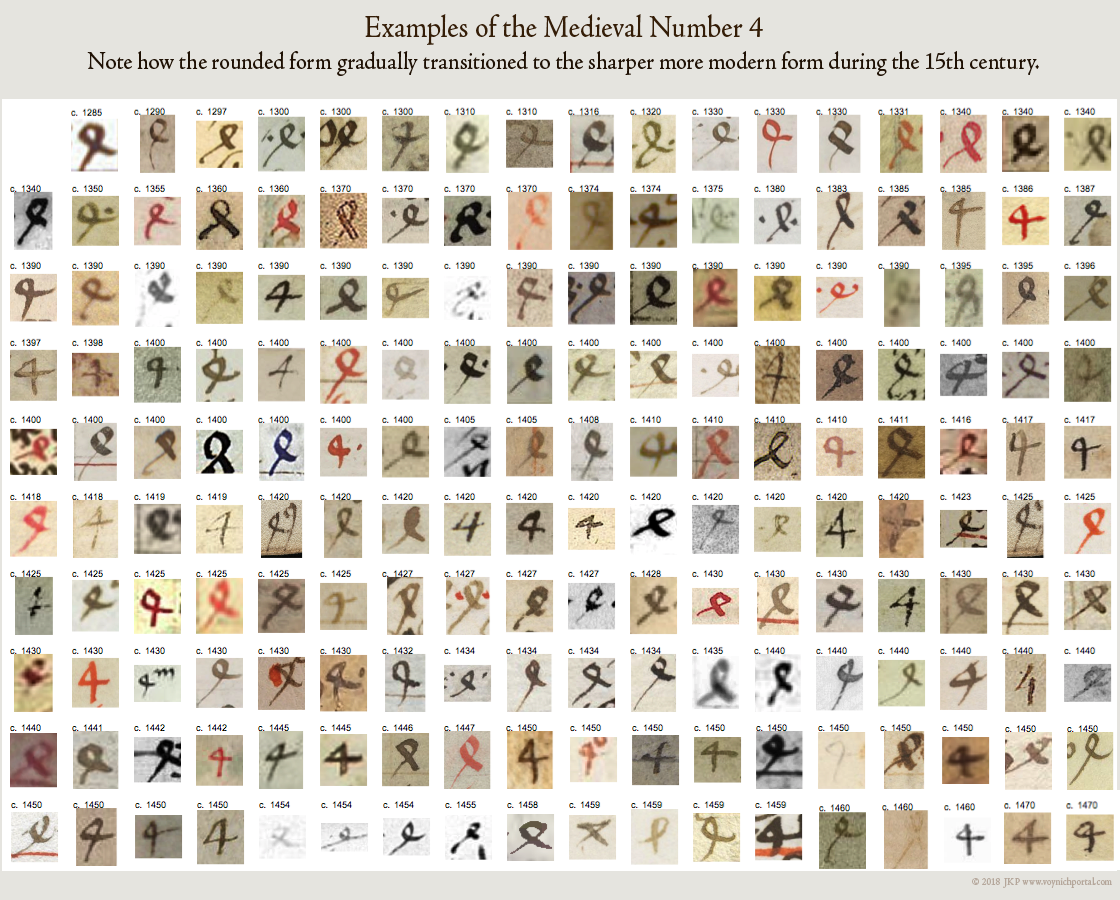

The following examples, dating from the 14th and 15th centuries, illustrate how the shape of the four gradually changed from the rounded form to the sharper, more modern form. Note how the sharper form starts to show up in the late 14th century and is more frequent by the mid-15th century:

Is 4o one character or two?

In the VMS, “4” and “o” are strongly associated, just as “th” or “ly” are strongly associated in English, but I don’t see anything that points to them being one character. If you write t + h to create a “th” ligature, they are still two different letters. The same applies to 4 + o in languages that use Latin conventions—they are written together but still represent separate characters.

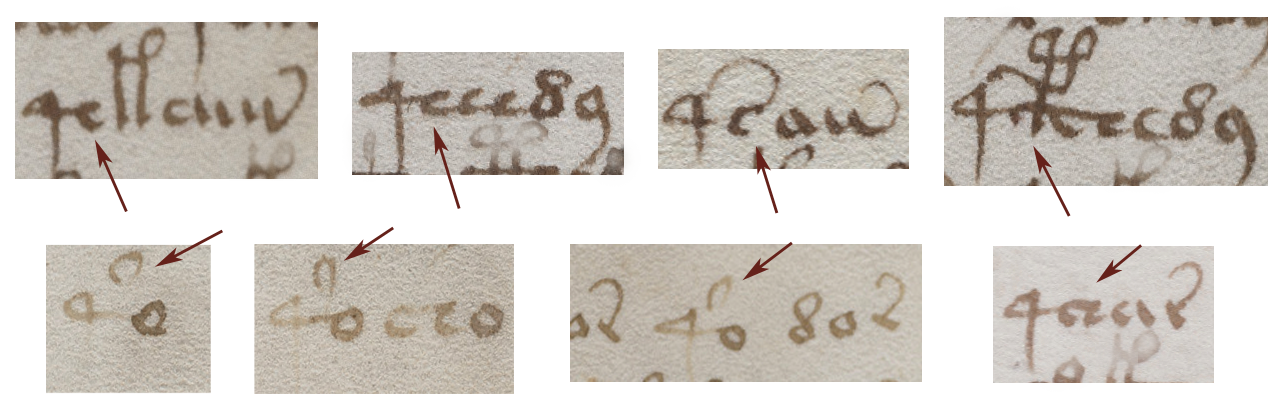

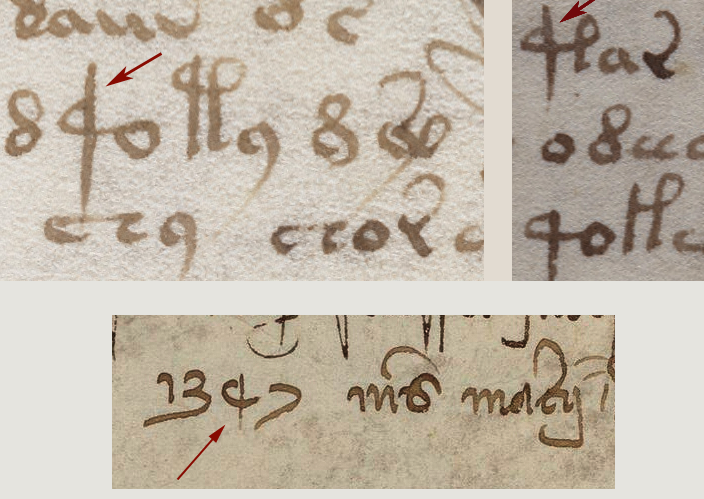

As I have illustrated in previous blogs, the VMS “4” glyph is not always followed by “o”. Sometimes it is followed 1) by other glyphs, 2) by a macron (which, if it were Latin, would indicate missing letters), or 3) by a shape that resembles a small Gothic “l” or the right leg of EVA-k or t:

Another picture I’ve posted before is the long-stemmed glyph that is similar to the “4”. Is it the same glyph or something different?

I’ve updated the sample by adding a date from a 14th-century manuscript that doesn’t completely answer the question but shows how diverse numerals could be in the Middle Ages. It’s not even clear if the marked letter is a 4 or a 9. It’s an oddball numeral that I’ve only seen once, yet it struck me as similar to the oddball character in the VMS, with a shorter stem but a similar swooped curve. At least we know from the context that it’s a number:

Is 4 a prefix that doesn’t require “o”?

There are many “o” words in the VMS and the “o” character sometimes stands alone. It’s possible “4” has an affinity for “o” words rather than “4o” being a character. Perhaps it’s a marker or modifier. Maybe it’s a number.

The 4 char has some interesting properties. It appears only once on f1v, yet is numerous on f3r. Voynichese is highly repetitive, but it’s not like homogenized milk, there are peaks and valleys, and 4 is not always at the beginning of tokens.

To really understand it, it has to be determined if sharp-4, round-4, and long-stemmed “4” represent the same thing, and it should be remembered that the “o” that follows “4” might relate more strongly to what follows than what precedes it.

J.K. Petersen

© 2018 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserve

Qu for 40 makes a great deal of sense, particularly in light of your research. I had been thinking of it as a Ju, maybe a capital J, for Jupiter, Juno, Judah, Julian calendar, etc. So an angular 9 (which seems to be an i/j sometimes, depending on position). They both make sense but I think q makes more sense!