The container on f89r of the Voynich manuscript has always struck me as an attempt to draw transparency. The bulbous part near the top (below the finial), and the narrow stem, seem to be encased in an outer layer. It would be difficult to create patterns like this out of crystalline stone, but fused glasses sometimes look like this.

I don’t want to get too tied to the idea of glass, but if it is glass, could such a container be fabricated in the 15th century?

Antique Glass

I’m familiar with Murano glass and Bohemian glass in general, I have antique glass in my personal collection. I saw some exquisite etched glass while traveling through Hungary. Italian glass is well-known and has been actively traded through Venice for hundreds of years, but was glass technology sufficiently advanced in the 15th century to create vessels as fabulous as the one in the VMS?

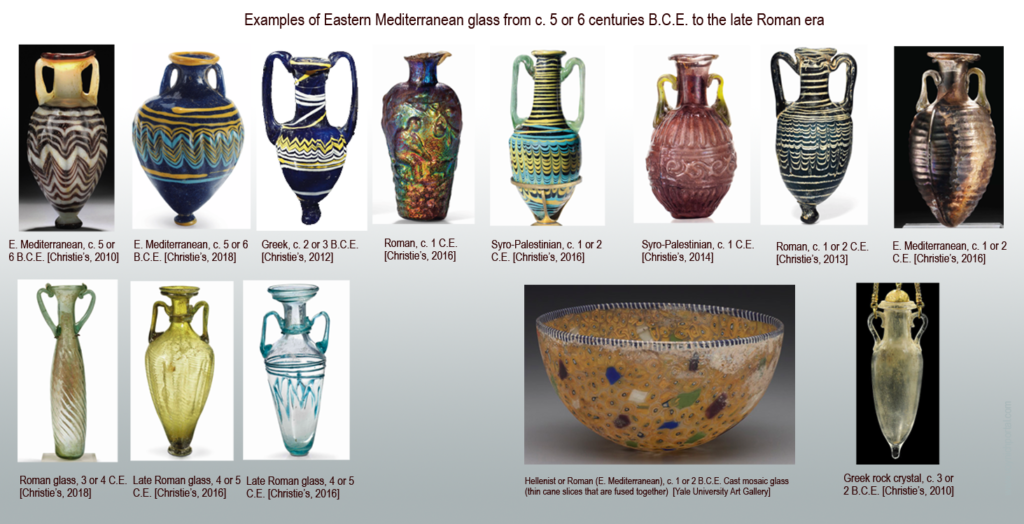

I don’t have enough free time to research and answer this intriguing question, but I gathered a few pictures of amphoriska that demonstrate that glass-making in Greece, the Levant, and the Roman Empire, were quite sophisticated in earlier times. Most of the following artifacts were created 2,600 to 1,500 years ago.

We can see from the examples, that glassmakers knew how to create translucent, feathered glass in multiple colors approximately 2,500 years ago, and that iridescence and the use of sliced canes (the ancient equivalent of millefiori) had also been achieved by the Roman era. Molded and patterned surface textures (both added and intrinsic) were also part of the glassmaker’s repertoire (click to see larger):

The detail in these little amphorae is extraordinary, considering they were only about 3″ high. Note that the detail in the carved rock crystal (bottom-right) was also remarkable—equal to that of many blown-glass vessels.

Signed pieces from the early Roman era also demonstrate a high level of skill in creating molded pieces, some of which compare favorably to glass housewares from the 1940s.

Layered Glass

But what about cased glass, one of the techniques that might result in a container similar to the VMS drawing? Cased glass is glass that is fused so one color shows through another (e.g., transparent glass over colored glass) and is sometimes cut to further reveal the underlying layer. It’s more difficult than fusing multiple colors within the same layer.

Bohemian glass from the last couple of centuries is well-known for this technique (Egermann and Moser pioneered some of the modern methods). Beads made from slices of caned glass (sometimes called “eye” glass) go back to the ancients but I was not able to find ancient artifacts that had a layer of translucent glass fused on top of colored glass in a curved vessel.

The closest I was able to find was “cameo glass” like the magnificent Blue Vase from Pompeii (right), held in the Naples museum (a museum that was “on strike” when I attempted to visit it years ago), but it does not have the same effect as cased glass in which translucent over colored is used instead of the other way around. Still, it does demonstrate the great level of sophistication achieved in ancient times. Some of these techniques disappeared for a few centuries during the Middle Ages.

Medieval Glass

Progress does not occur in a straight line and knowledge is sometimes lost. Millions died in famines, plagues, and wars, and their skills and trade secrets died with them. The techniques illustrated by the ancient amphoras can all be found in Europe in the 16th century, and a century later many new techniques were developed to reproduce ancient styles. But how much was known in the 15th and 14th centuries?

It was quite common for medieval glassmakers to add blobs of transparent or translucent glass as decorative additions. Engraved glass was not uncommon either. Glass enameling and a medieval form of “carnival” glass existed by the 15th century. Metal and glass were frequently combined, but it’s a struggle to find vessels in which a layer of translucent glass was fused on top of a colored layer.

If the VMS container is glass (or possibly glass with a metal base), it might not be cased glass. It might be translucent glass with an embedded pattern of colored glasses. The pattern does not look feathered, and appears too even and regular to be caned glass, so it is not an example of the most common styles, but if the vessel is partly imaginary, or a design for something that was not practical to fabricate, then the imagination of the illustrator may have embellished it.

Maybe it’s not glass at all. Maybe it’s one vessel behind another, or two different ideas for the same vessel. Or maybe it’s like a Russian doll, one vessel inside another, but drawn to show both.

I’m hoping that it’s at least partly glass, I like glass, but I’d better not hold my breath. VMS research has a way of stretching out longer than one expects.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2019 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

Postscript Feb 22, 2019:

I didn’t post this image in the above article because it’s a rights-managed Getty image, and blog readers often don’t click on external links, but I wish I had because it illustrates similarities to the VMS containers that are strongly associated with the 15th century.

It’s a goblet made in Murano with a finial similar to the VMS container (which could be glass or metal). This kind of finial is not difficult to make in glass and is also common to Egyptian glass, so it’s not the primary reason I chose this example. What I suggest you pay attention to is the regular pattern of raised, applied enamel dots, a style and fabrication technique that was not typical of ancient glass:

Now hold that dot style in your mind and imagine it applied to a raised, translucent pattern, as in these Murano vessels (in the Museo del Vetro). Clear glass was a significant innovation of the early 1400s and from that point on was often combined with colored elements:

Scale motifs are found in almost all cultures, they are not exclusive to glass or to Murano, so I try not to get too excited when I see them, but every time I come across them, I am reminded of the many scaly patterns in various sections of the VMS.

Postscript Feb. 24, 2019:

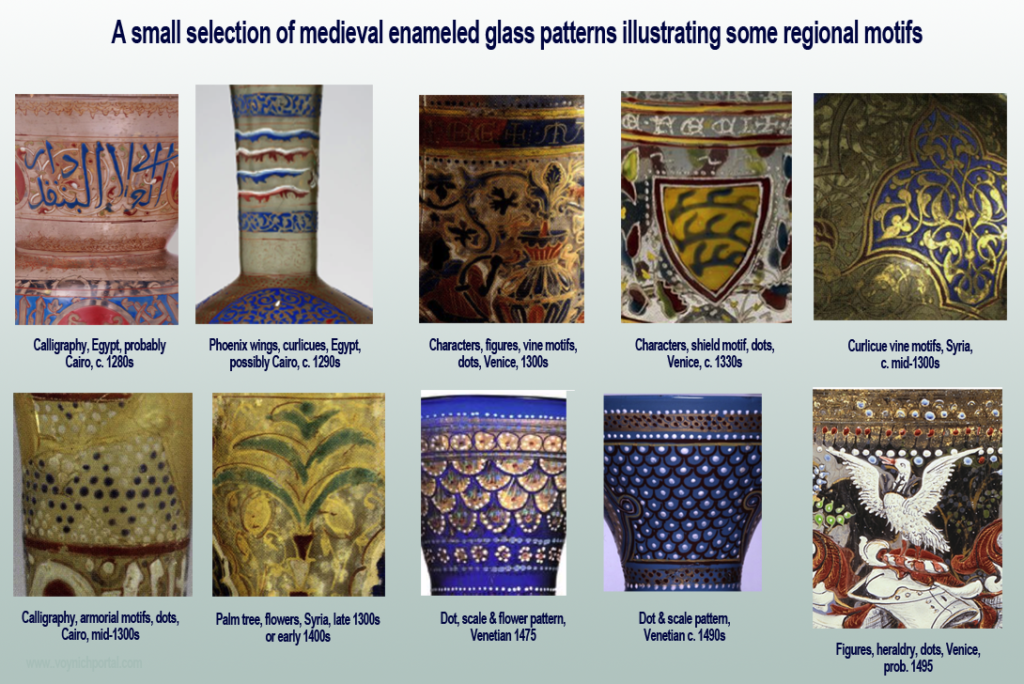

I thought it might be helpful to include a few examples that illustrate regional differences in enameled glass motifs from about the late 1200s to the late 1400s:

JKP – If you’re accepting comments…

I came to the same opinion as you – that the object is made of glass.

I believe the top part is pierced-work, i.e. that it’s a scent-diffuser.

You can see an example of another object formed as ‘pineapple’ pierced-work depicted on an enamelled glass recovered from Begram.

The lower section of the object in the Vms contains the scent itself, and it is shown half-full.

This is was one of numerous details in the manuscript – and not just this section – which led me to conclude that a substantial proportion of it had been first enunciated in the Hellenistic east between the 1st-3rdC AD.

The process for enamelling glass survived there too, and returned to the eastern Mediterranean only around the 12thC . We know from the designs on the 12thC glasses that knowledge of the technique had followed the trade routes from the Indo-Persian contact region (i.e. that of old Bactria).

Recently, Marco Ponzi mentioned a paper by David Pingree about the transmission lines from that same region of images for the Decans and Horas – Pingree is just one of a number of scholars who have worked on the subject of the decans and horas’ transmission, but the point is that once more the origins are right, the right line of transmission too , and the time. By ‘right’ I mean in accord with the information offered by the Vms imagery.

I think it rather a pity that I weren’t first sharing that research now rather than in 2010, when even to mention European trade with medieval Egypt was to be scoffed at, and anyone who dared quote me was displaying exceptional independence of mind.

Here’s the Begram glass, showing the ‘pineapple’. Note the headband on Penelope, and the palette (I mean, the range of colours used on the glass).

https://qmnblog.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/alex-enamelled-glass-beaker-low-res1.jpg

D. O’Donovan wrote: “I came to the same opinion as you – that the object is made of glass.”

I’m not certain it’s made of glass. Cut crystal, like the little amphora I included in the bottom-right of the chart, can be cut and smoothed with a great deal of precision. Or, the drawing might be trying to express something other than glass (double containers or double layers, for example). It LOOKS like it might be glass (I rather hope that it is), but I don’t want to assume so without more evidence.

D. O’Donovan wrote: “This is was one of numerous details in the manuscript – and not just this section – which led me to conclude that a substantial proportion of it had been first enunciated in the Hellenistic east between the 1st-3rdC AD.”

That seems to me to be a bit of a leap in logic.

Whirled, feathered and caned glass were the primary patterns used in colored Hellenistic vessels and the VMS container doesn’t include those patterns. Hellenistic influence is found in many aspects of medieval art and literature—people of the Middle Ages looked to the ancients just as we do today—but my main thrust was to discover whether the knowledge and techniques used in ancient times were still known and used around the 14th and 15th centuries and it appears that some of these skills disappeared for a few centuries, to be gradually resurrected from the late 15th century onward.

It still remains an open question whether they were capable of fabricating this in the early 15th century (or thereabouts). If it is, in fact, meant to represent layered/fused glass (in the style of cased glass), then it is ahead of its time. I was not able to find any Hellenistic examples of cased glass in which the transparent layer is fused over a colored one (the style made popular by Bohemian glassmakers Egermann and Moser in the early 19th century), although the Blue Vase (opaque over translucent) shows that they might have had the technical skills to do it.

If the VMS vessel represents something else (e.g., colors mixed in the same layer as transparent elements), it’s still fabulously ornate for its time and would only be available to a wealthy few. The creator of the VMS either had a very rich imagination or very rich friends.

JKP

I expect that as a single sentence, it would seem like a leap in logic. What it is, actually, is the result of bringing four decades of research and experience to bear on investigation of this manuscript. It’s actually a pleasure to see others now following along the same lines, albeit nine years later. Sooner or later, if one has got it right, it’s inevitable that someone will make the same connections, from the same textual, archaeological and other sources too. It’s a good thing. It is just so much simpler a process if work is acknowledged, and properly attributed to its source – just as people have begun to do more often.

Back then, when I began trying to contribute to the study, the online community – well, not all of them – tended to treat everything as if it were speculation or theorising, and so the end-result of academic-style research was treated as no more than an ‘idea’ being tossed up into the air.

Things have changed a lot since then, and especially of late, there’s a spring wind as it were. It’s such a heartening sign to see the manuscript granted equal dignity with other medieval works and taken seriously at last that I’ve even written a post about it.

Thanks for posting the comment, and for the reply.

Diane, I know you have frequently mentioned Hellenistic influence in connection to the VMS. You’ve also mentioned Spanish, Iranian, and Indian.

My reaction has always been the same. ALL of medieval art and literature is in some way touched by Greco-Roman influence, it’s part of the history of Europe. There were Greek colonies in many regions in the Middle Ages (including Provençe, southern Italy, the Mediterranean islands, and others). There were also a couple of significant revivals in learning the Greek language in the 14th and 15th centuries. Scholars wanted to read the ancient texts.

Latin script is full of Greek scribal conventions. Indian literature (esp. Sanskrit) uses the same concepts. Medieval herbal literature was largely descended from Greek manuscripts. The Juliana Anicia Codex is in Greek.

Just as European culture greatly influenced the history of the Americas, the Greeks and Romans greatly influenced the history of the Middle East and Europe, from Pakistan to northern England.

So how does one distinguish which aspects of a manuscript relate to the natural evolution of culture, and which ones might be related to the cultural background of a specific person? Early medieval manuscripts from France have drawings with unusually long fingers as one might see in Indian cultures. Sixteenth-century Iranian art is full of Chinese motifs.

In the Middle Ages, there were Greeks living in Marseille and Florence, and Scandinavians living in Lombardy and the northern coast of Africa. Greeks living in Marseille are going to have a different culture perspective from those living in Athens. Scandinavians living in Africa will have a different culture from those in Schleswig.

Did the person or persons who designed the VMS come from another culture? Quite possibly. People were mobile. Immigration was easier in those days than it is now. There were foreign colonies everywhere. I don’t see anything particularly unusual in the possibility of multicultural influence.

I found this, 15th century perfume bottles, Italian, Metropolitan Museum of Art

https://66.media.tumblr.com/tumblr_m5kcalaOqN1r60zczo1_r1_540.jpg

Nice examples. A shame the photo is so small.

If I had to guess the date of those I would have guessed 16th century, so perhaps they are very late 15th century? They seem very polished (in the skill sense) and “sure”, something that is less characteristic of early 15th century glass.

Nice variety of styles and techniques. I always enjoy looking at glass (as a child I was enraptured by glass artisans creating mouth-blown glass, and would have watched them for hours if my parents hadn’t dragged me away).

Thanks for the link.

I had the same thought that it was late century. I didn’t find any more info on it.

Just now though, i found this from 1300 Germany. Not the shape of the glass but the painted figures, they resemble nymphs’ faces somewhat, including the splotches

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/46877/46877-h/images/plate-01.jpg

From http://www.gutenberg.org/files/46877/46877-h/46877-h.htm

I also found this from 1400 Florence

https://www.wga.hu/art/zzdeco/1gold/15c/01i_1399.jpg

Hope it helps!