25 February 2020

I found the series Ma Me My Mo Mu in a mid-15th-century German manuscript. This surprised me. If you know east Asian languages, you will recognize the syllabic nature of this series. Another sequence in the German codex is Ba Be Bi Bl Bo Be Bu.

So which language is it? It has elements of Japanese or Filippino but isn’t quite a perfect match for the order or the components. It’s unlikely that Japanese was known in the 1460s in Europe. Could east Asian languages have been recorded earlier than we realized? Or is it an African language (some of which are similar to Asian languages)?

Syllables and Numerals

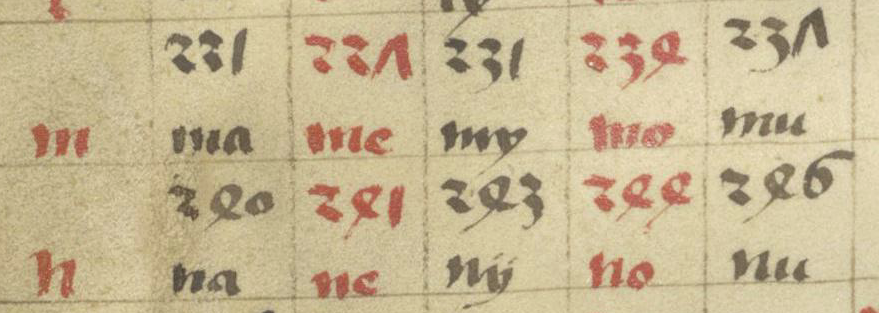

First I’ll introduce you to the manuscript. If you glance through the chart on Barth 24, f1v and you know Japanese, this sequence jumps out: ma me my mo mu (note that medieval languages often substitute “y” shape for “i”)…

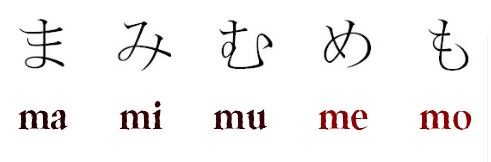

If you read the fragments in this order: black, black, black, red, red, you get ma, my, mu, me, mo which is the correct order for Japanese syllables. Here is the Japanese, with Hiragana equivalents:

But the syllables in the German manuscript are out of order. You have to read the black ones first, followed by the red ones, to get the correct sequence in Japanese. Is this because a medieval scribe or missionary got it wrong? Or because it’s not Japanese but perhaps a related language with a slightly different order?

It turns out it’s not a language at all, it’s a system based on language components and, even more surprising, it is remarkably consistent across unrelated languages. The same system is used in German, Spanish, English, and (believe it or not), Malaysian. Could this be relevant to the VMS, perhaps in more than one way?

It turns out that the German manuscript is a dictionary but not a Romanized-Japanese dictionary. The numbers paired with syllables in the above example refer to folios, and when I looked up an unfamiliar word in the “M” section on Google search, it took me to a word in Tagalog. Once again, I thought, did missionaries compile this? And yet the rest of it looked like Latin (and read as Latin).

The word I selected turned out to be one very big coincidences. It is Latin. The manuscript is Catholicon, and I coincidentally picked a word that is also valid in Latinized Tagalog.

So what are these syllables if they are not Japanese or Tagalog?

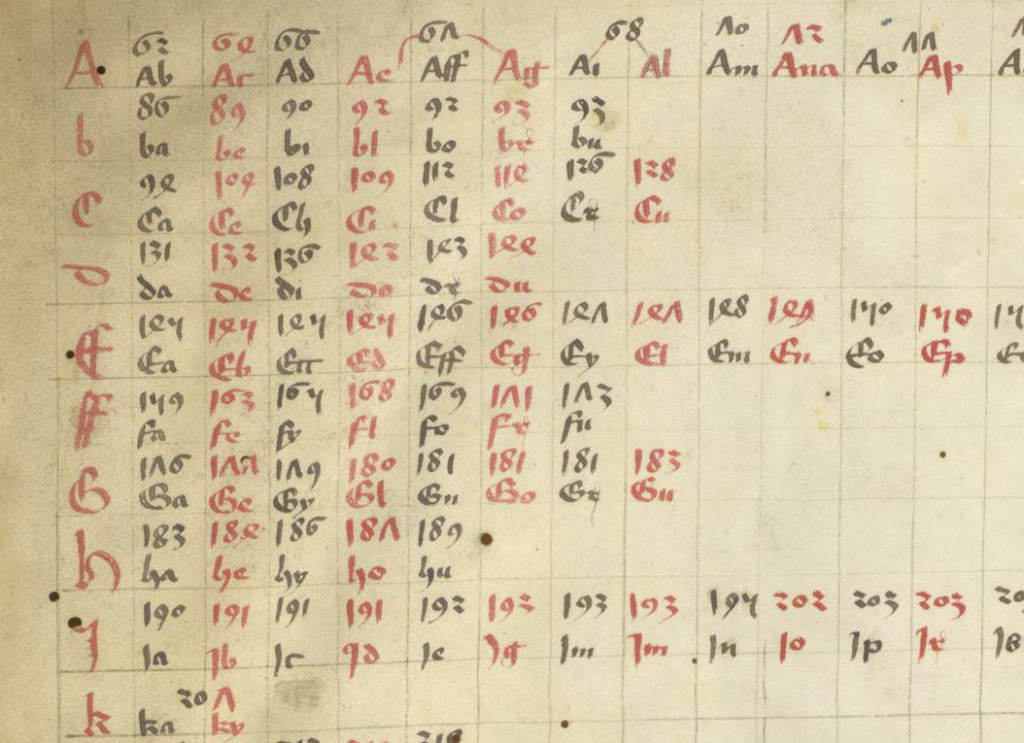

Here is a larger screensnap so you can get a sense of the overall system. The numbers above the syllables are folio numbers:

It took a bit of research to find answers, but I learned that this is a medieval indexing system, one that was designed for large datasets.

We’re used to indexes with numbers accompanying short words and phrases. The one above is a little different and reaches us from the minds of people who lived more than 500 years ago, and it’s still valid! In the post-medieval centuries, it was adapted by schools to teach writing, and by American companies to sell filing systems and insurance services. It is still in use today for a wide variety of purposes.

The system is based on the lookup characteristics of common syllables at the beginnings of words and it’s almost spooky the way it generalizes across unrelated languages. It appears that basic and common sounds at the beginnings of words are somewhat universal despite dramatic differences between western and eastern languages.

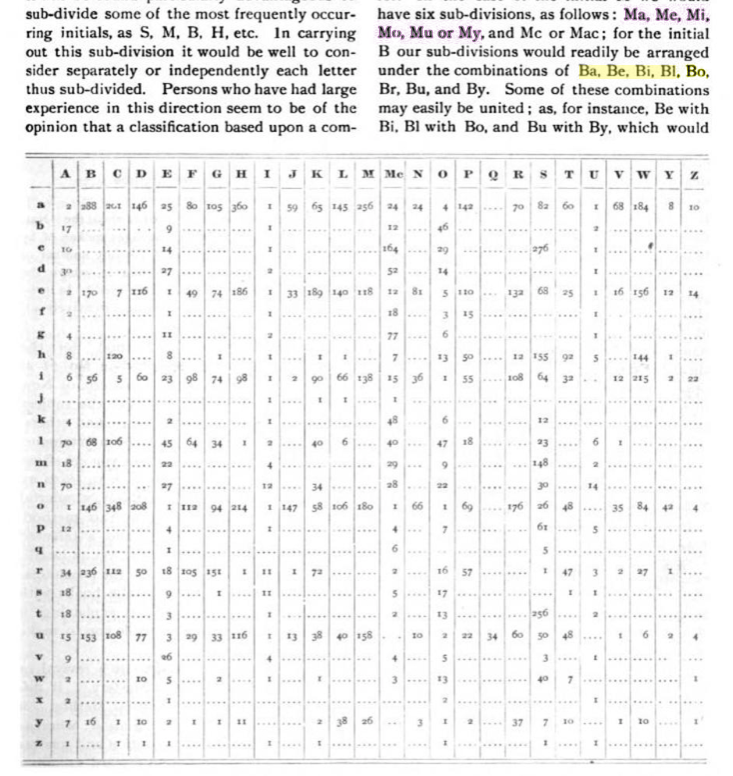

Here are some examples. The first one is an indexing system used in American accounting systems in the 19th century. Note the M and B sequences:

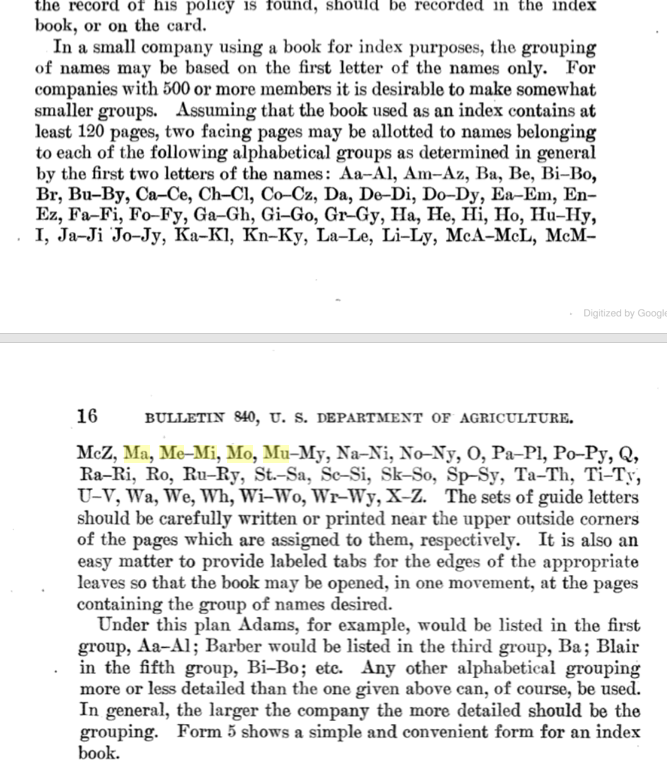

Here is another example of indexing for large sets of names (companies with 500 or more members). Note Ba Be Bi Bo Br Bu (not identical to the German example Ba Be Bi Bl Bo Be Bu, but close and also close to the Japanese Ma Me Mu Me Mo alphabet sequence:

The instructions for this system say to write the “guide letters” near the upper outside corners of the relevant pages (similar to folio numbers). It should probably be emphasized that even though medieval manuscripts were sometimes annotated with quire numbers prior to being sold, they were usually foliated by the purchaser, his heirs, or the bookbinder’s assistant when it was taken in for binding (sometimes decades or centuries after it was created).

Indexing didn’t always happen when a book was bound, sometimes the index was added weeks or decades later, but when it was professionally indexed, the indexers took their jobs very seriously. It could take months to critically analyze the manuscript, to annotate the margins and, finally, to create the index (as an example of this process, see BNF Latin 15754). In a sense, the index was like a Cliff Notes version of the manuscript.

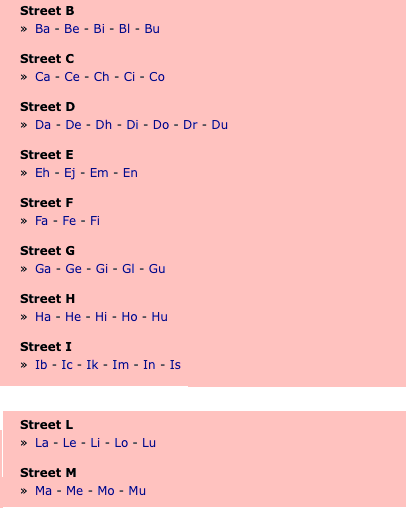

So how could this indexing system possibly relate to east Asia? Well take a look at this 21st-century sequence for indexing street names in Malaysia:

I have removed “J” because it was generally non-existent in medieval Europe (what looks like a “j” is usually an embellished “i”) and also k because there are many more “k” syllables in 21st century Malaysian names than most western medieval languages. It is not a complete match by any means, but considering that German and Malaysian languages are very different, there are a remarkable number of matches in content and sequence.

This unexpected linguistic continuity gave me food for thought. I wondered… can this characteristic of languages have any relevance to the VMS?

Are There Indexes in the VMS?

Maybe. Here are some things to consider…

- Some manuscripts were almost entirely indexes, which means the word patterns don’t match full sentences and numbers are frequent.

- Some manuscripts, even long ones, had no indexes at all.

- Some had brief section indexes (note the folios in the VMS that resemble “key” pages).

- Some depended on an index as a separate volume.

- Some had long indexes, extending for several folios (not unlike the dense text at the end of the Voynich Manuscript). Sometimes each entry was notated by a symbol such as a cross or flower.

Summary

Numerous insights can be gleaned from this. First of all, it shows there are aspects of language that are similar among western and Asian languages. The sample posted above demonstrates this with startling clarity.

Maybe it explains why Voynich “solutions” have been offered in a dozen different languages with many solvers (and statistical analysts) feeling strongly that it matches their language of choice. Perhaps we are seeing fragments (as in an index or as in words that have been broken into syllables with extra spaces) that follow patterns common to a number of languages.

Or perhaps the VMS (or portions of it) comprises an index which, in the middle ages could sometimes look like a student notebook, with many note-style annotations interspersed with numbers.

The concept of multiple volumes existed in the Middle Ages. There are a number of medieval herbals designed with separate text and illustrations. Bibliographers and historians have suggested that certain specific books, in a variety of subjects, may once have had a companion volume.

But does this apply to the Voynich Manuscript?

It’s my opinion that many of the VMS “labels” are not words, at least not if space boundaries are retained. Maybe they are references rather than names. It seems intuitively obvious to look for label matches in the main text (and I, of course, have done this as well), but this isn’t the only way to cross-reference. Label text doesn’t have to match the exact pattern of glyphs in the main text to function as a reference. It just has to “point” in some way (e.g., referencing a folio number, section, paragraph or quadrant, or perhaps a separate volume), a process that would result in a high degree of repetition and self-similarity.

I have seen cross-referencing in medieval manuscripts. There is an herbal in an English repository that cross-references the same plant in another manuscript, with a short annotation near the root. It is also very common in Greek herbals for illustrations in the margins to include an indexed number (written as letters) that references a formal index or some part of the text.

Even so, it should probably be noted that the VMS has quite a lot of text, most of it carefully integrated with the illustrations, which seems to speak against a companion volume, but if the VMS glyphs represent a verbose code, as one possibility, then the information content could be much lower than it appears.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright Feb. 2020, J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

JKP – very interesting post.

The part which intrigues me most is where you say, “I learned that this is a medieval indexing system, one that was designed for large datasets.”

I’d be interested to know where and when the system is first attested, and for how long it was used, the range over which it is known to have been used, and whether it was first devised for secular, or for religious libraries, or appears in both from about the same time – whatever that might be.

DId your source cite many non-German examples, and especially from fourteenth century?

With regard to the Voynich glyphs, it occurs to me that if you can correlate the ‘mi mo mu’ with specific glyphs, Julian Bunn’s colour-coded pixel-grids may be of value to you. He also concluded that the Voynich ‘vords’ weren’t words at all.

Thanks.

“I’d be interested to know where and when the system is first attested, and for how long it was used, the range over which it is known to have been used, and whether it was first devised for secular, or for religious libraries, or appears in both from about the same time – whatever that might be.”

I don’t know where this indexing system was first attested (it may go back to ancient times) and whether it was originally devised for secular or religious libraries (it’s possible that no one knows the answer to this). If you have an interest in ancient and medieval indexing systems for large datasets, I’m sure you can find research sources to follow up your questions.

“He [Brunn] also concluded that the Voynich ‘vords’ weren’t words at all.”

I have not concluded that the Voynich tokens are not words. I stated in this blog that I don’t think most of the labels are words, at least not if the spaces are taken literally, but I think it’s too soon to generalize this impression to all the text.

JKP – Hope the following may be of interest to you and other readers. It’s all I can find in my sources and doesn’t answer the broader questions, but may shed some light..

“Another interesting decision was made in the catalog of the library of the Augustinian

Friars at York, compiled around 1372. Here, the cataloger assigned letters of the alphabet to

each book in each subject class. Letters were repeated or combined with symbols when necessary. In this way, a book listed by its letter then its content clearly shows which titles are

contained therein, avoiding the problem of titles running together.[44] While these organizational

schemes may seem to modern librarians as “stopgap” measures which do not fully compensate

for lack of access to each title and subject, they obviously served their purpose in the libraries

they described.”

I have that information from

Beth M. Russell, ;Hidden Wisdom and Unseen Treasure: Revisiting Cataloging in Medieval Libraries,

[in journal..] Libraries and Classification Quarterly, 1998, vol. 26, no. 3, p.21-30.

The source which Russell cites in her footnote [44] is

Dorothy May Norris, A History of Cataloguing Methods 1100-1850: With an Introductory Survey of Ancient Times, (London: Grafton & Co., 1939) p.51