Author Archives: J.K. Petersen

Large Plants – Folio 39r

Large Plants – Folio 38v

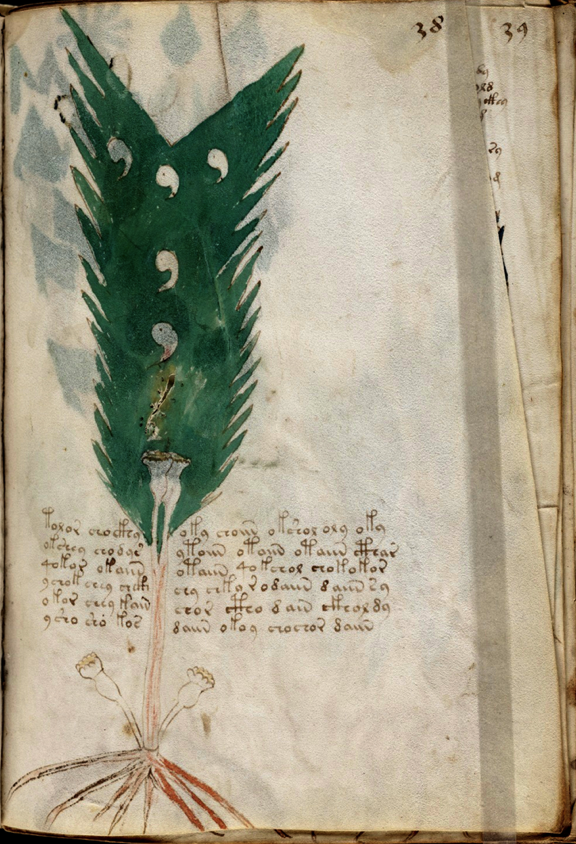

Voynich Large Plants – Folio 38r

In 2013, I posted some initial impressions of Plant 38r, stating that the “apostrophes” probably represented droplets (sap), but I couldn’t find enough public-domain images to fully explain what I feel it represents (posting an idea is one thing, convincing people that it’s a valid idea is entirely another) and opted to redact it rather than leaving it half illustrated. Since then, many more botanical images have been added to the Web and I finally have enough visual aids to demonstrate the logic behind this choice. — May 3, 2018

Description

Plant 38r is a tall narrow drawing inhabiting the entire vertical space. Note how it has been slightly crowded toward the left of the folio. The sheet itself is narrower than others, with a long triangular section missing from the top right so that the text from folio 39r is visible.

Plant 38r is a tall narrow drawing inhabiting the entire vertical space. Note how it has been slightly crowded toward the left of the folio. The sheet itself is narrower than others, with a long triangular section missing from the top right so that the text from folio 39r is visible.

The drawing has a jagged green background against which are unpainted yin/yang-like symbols with a single carefully placed dot in each one.

There is a jagged line underneath them where the parchment has a hole that was at one time stitched and, below that, is a pair of vase-like shapes coming out of the stalk with a pale amber color painted inside, perhaps to give it a more rounded 3D look.

The vase shapes converge into a stalk that has been lightly brushed with reddish-brown and the bottom of the stalk sports two additional vase shapes splayed to each side. The base spreads into finger-like roots—brown on the left, reddish-brown on the right. A single paragraph of text fits around the plant where it narrows into the stalk.

When I first saw it, I wondered whether one could interpret the top green part as a river or stream. There are a number of herbal illustrations of water-cress, hepatica, and several aquatic weeds that are drawn within or along river-banks, but there are other aspects to this drawing that suggest the green area is probably representative of leaves rather than water.

I find it interesting that the average number of tokens per line on this folio has been reduced in much the same way as the width of the plant. Perhaps the scribe adjusted the text in anticipation of the sheet being trimmed to make it straighter?

Prior Identifications

I hadn’t seen any prior IDs at the time I worked out an explanation for this plant but it strikes me as metaphorical in some ways and literal in others and when I started exploring herbal manuscripts, I saw a pattern that might account for its features.

I think the height of Plant 38r, which touches the top of the folio and runs off the bottom edge, might be an indication of scale. The green area has a feather-, palm-, or fern-like quality, but if it’s meant to be a large plant, then some relationship to palm trees (or trees or large shrubs with fern-like leaves) seems more likely than allusions to feathers.

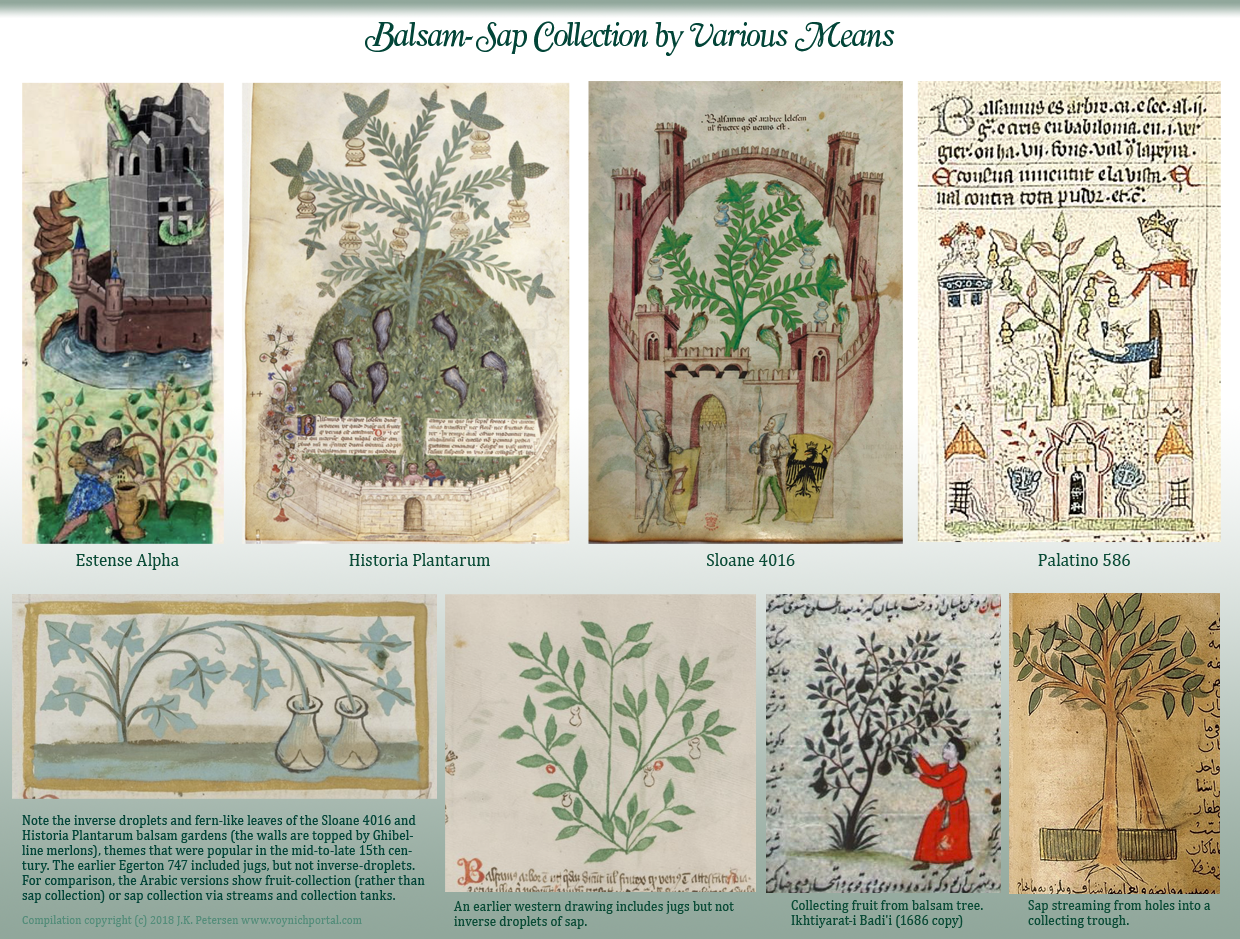

So, imagine for a moment that the green area represents leaves or a garden and the yin shapes are droplets, then the vase-like shapes beneath them might simultaneously represent flowers and receptacles for collecting sap. Sap was harvested from quite a number of plants, including date palms and the rare balsam tree, which is said to have been cultivated within guarded and gated gardens. The saps were variously used as sweeteners, perfumes, and medicinal resins.Thus, it’s not surprising that quite a number of herbal manuscripts include drawings of walled gardens and jugs for collecting sap, sometimes hung on branches, other times held in the hands of the workers [click to see larger].

Note how the droplets are drawn, with the tail facing down, the opposite of what one would expect if they were falling. The VMS drawing orients them tip-down, as well. Note also the fern-like way some of the leaves are drawn, even though balsam trees don’t immediately strike one as fernlike until one looks closely and simplifies their basic structure. The fern-like approach was more common in the 15th century. In the 14th century, the leaves were usually elliptical.

How Herbal Traditions Relate to the Voynich Plant

I am fascinated by the possibility that the VMS drawing depicts a plant that is harvested for sap, because there is still considerable debate over whether the VS plant images follow eastern or western traditions (personally I don’t think the dividing line is as cut-and-dry as some people suggest, since there was considerable copying in both directions, but there are some overall patterns). For example, the theme of vines twining around plants with oak-like leaves that I blogged about in 2013 is found in western manuscripts, but is it a solitary example (or a coincidence)? or are there several drawings in the VMS whose traditions can be identified?

I am fascinated by the possibility that the VMS drawing depicts a plant that is harvested for sap, because there is still considerable debate over whether the VS plant images follow eastern or western traditions (personally I don’t think the dividing line is as cut-and-dry as some people suggest, since there was considerable copying in both directions, but there are some overall patterns). For example, the theme of vines twining around plants with oak-like leaves that I blogged about in 2013 is found in western manuscripts, but is it a solitary example (or a coincidence)? or are there several drawings in the VMS whose traditions can be identified?

As far as I can tell, the inverse-droplet-and-jug theme is western, and wasn’t prevalent until the 15th century. You might notice that the Arabic manuscript included in the compilation above depicts sap collection in quite a different way, with liquid streaming from holes in the tree into a collection-trough at the base—no vases or droplets. The image to its left shows no sap collection at all, the “jugs” are actually fruits being harvested (probably Momordica “balsam apple” which is different from the resin-balsams). I am still keeping my eyes open for non-Western manuscripts with jugs and inverse-droplets but haven’t seen any yet.

As can be seen from the examples directly above, 14th-century images of balsam don’t typically include inverse-droplets (although sometimes they include vases or buckets), and tend to focus on naturalistic aspects of the plants. By the 17th century, accurate drawings of plants had largely superseded illustrations that incorporate the use and environment of the plant. So, the time period during which inverse-droplets were popular in herbal manuscripts is important to VMS research because it is temporally similar to the century during which crossbowmen appeared as Sagittarius in zodiac illustrations.

Why does the VMS drawing have dual-colored roots? I think it’s deliberate, not just haphazard paint application, but I’m hesitant to interpret it too soon. I’ll hazard a preliminary guess, however, that it might be because the Commiphora that produces Balm of Gilead and the Commiphoras that produce myrrh are quite similar, are harvested the same way, and are variously called “balsam” or, perhaps, that both balsam and date palm saps are represented.

Summary

Vase-like Commiphora bud [Photo detail courtesy of toptropicals.com]

If the VMS drawing represents balsam, or some kind of sap that is harvested like balsam, then it follows tradition in a number of important ways: it’s somewhat fern-like, includes a reference to collecting-vases, and includes droplets with their tails pointing down, all characteristics found in manuscripts of the early/mid-15th century. But it is also different in some significant ways. It is greatly simplified, includes no gates or castles, and yet has something lacking from the other medieval drawings… the unusual little flower “vases” characteristic of balsam trees, a detail that only someone interested in plants would notice because these buds quickly turn into little knobs. I’ve said many times that I think whoever drew the VMS plants wasn’t just a copyist, that it was someone who knew a few things about plants, and the addition of these buds seems to point in that direction.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright July 2013 and 3 May 2018 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved

Large Plants – Folio 37v

Large Plants – Folio 36v

Large Plants – Folio 36r

Voynich Large Plants – Folio 35v 21 July 2013

The VMS plants are more detailed than many herbal drawings of the 15th century, but this has not made identification easy. Some appear identifiable at first glance while others require study. The text is not helpful because, as yet, it has not been deciphered and even once it is, there’s no guarantee the text has anything to do with plants.

Description

It would take far too much space in one blog to trace herbal traditions that precede the VMS that may have influenced the way the plants were drawn but, at the risk of making even this post too long, I would like to offer an observation about the plant on folio 35v, which suggests, along with other clues, that the Voynich illustrator was familiar with some of the traditional texts.

It would take far too much space in one blog to trace herbal traditions that precede the VMS that may have influenced the way the plants were drawn but, at the risk of making even this post too long, I would like to offer an observation about the plant on folio 35v, which suggests, along with other clues, that the Voynich illustrator was familiar with some of the traditional texts.

Folio 35v shows a tall plant stretching from the top to the bottom of the page, with roots that reach almost all the way from left to right. There is either a single block of text on the left, or two blocks closely spaced.

The crenelated green leaves on the trunk of the central stalk, and at the top, resemble oak leaves and the roots are reddish brown. The central stem and the winding stem are roughly painted a slightly lighter shade of green.

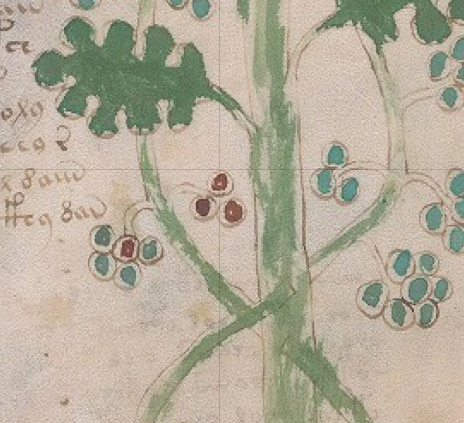

If you look at it a little more closely, you can see that there may be two plants on this page. I’ve mentioned this possibility in my description of Plant 49r, as well—that the Voynich images are not necessarily all drawings of single plants.

What appears to be a second plant winds its way around (and through) the trunk of the taller plant and has berrylike clusters at fairly regular intervals. The knobs are mostly aqua-blue, a color that doesn’t occur often in the VMS. A few are a slightly darker blue or red. Note that the berries are painted more carefully than the trunk and vine stems, as though the lighter ring around the edge was intentional.

What appears to be a second plant winds its way around (and through) the trunk of the taller plant and has berrylike clusters at fairly regular intervals. The knobs are mostly aqua-blue, a color that doesn’t occur often in the VMS. A few are a slightly darker blue or red. Note that the berries are painted more carefully than the trunk and vine stems, as though the lighter ring around the edge was intentional.

It’s possible that this is some kind of vine and perhaps the tree in the center is a host (either in the sense of providing a support for growth or in the sense of a parasitic host).

It’s difficult to identify the vine from a handful of berries. They might be grapes, they might be something else, they might be buds rather than berries. Also, notice the absence of leaves. In my post on Cuscuta, I suggested the vine might be paired in the drawing with its host plant. That’s possible here too. It’s also possible that the leaves drop in the fall while the berries remain. There are many plants that can be seen in winter with berries and no leaves. There’s simply not enough information to know, unless… we get some help from herbal tradition.

The Twining Vine

A vine from the Juliana Anicia Codex that follows the same basic format as that of De Materia Medica of, Dioscorides.

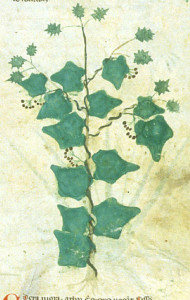

Assuming for a moment that the twining plant is a vine and that the round knobs are berries rather than buds, we can look at other depictions of vines in the old herbals to see if any are similar. What we discover is that some are thickly matted, some twirl in one direction tight against the host stem, and some wriggle through the air toward the top or side of the page (e.g., Pseudo-Apuleius). Most have leaves, or leaves and flowers, but some are shown with berries. Harley 4986 differs from most by emphasizing the berries, but doesn’t otherwise resemble Plant 35v.

So it would seem, at first glance, that the VM plant doesn’t follow previous traditions unless we delve a little further.

Herbals Originating from Other Regions

There is a picture of common ivy in Harley 4986, in which the berries are emphasized to the point of looking like grapes, but the drawing is not otherwise similar to Plant 35v—it includes leaves, doesn’t noticeably twine, and doesn’t include a host. Morgan M.873 twines the vine around the host and includes berries but doesn’t show any leaves on the host.

There is a picture of common ivy in Harley 4986, in which the berries are emphasized to the point of looking like grapes, but the drawing is not otherwise similar to Plant 35v—it includes leaves, doesn’t noticeably twine, and doesn’t include a host. Morgan M.873 twines the vine around the host and includes berries but doesn’t show any leaves on the host.

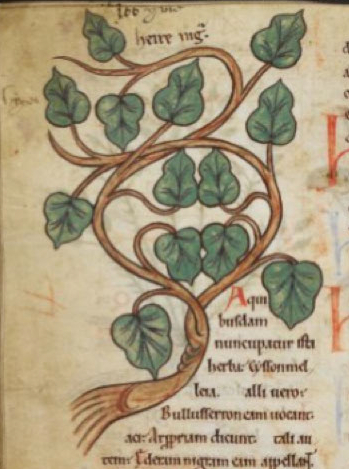

In Harley 1585 (pictured left), an herbal manuscript from the Florentine area, and Ashmole 1462, (copied from H. 1585), there is a vine worth noting because it almost forms a figure-8, but it’s not a great match for the vine on Folio 35v in other ways, even if it’s closer than the ones previously mentioned.

Herbals That May Have Influenced the VMS

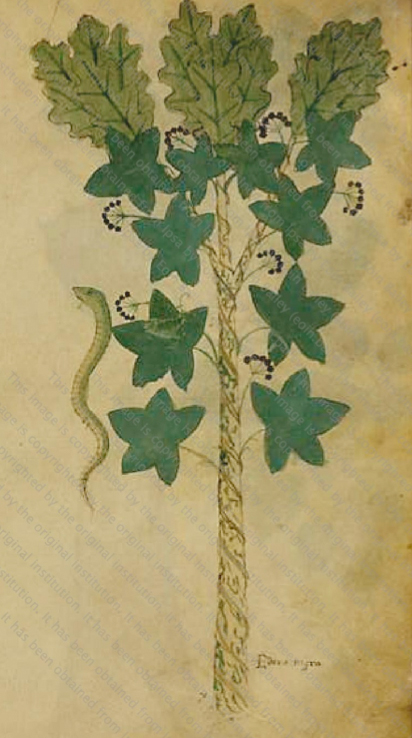

In Liber de herbis et plantis an extensive, well-constructed herbal from the 1300s, we find a number of features that might have inspired Plant 35v. The vine twines around a host, there are clumps of dark-colored berries and, an important detail, the host has crenelated oak-like leaves. Plant 35v resembles the Liber de herbis diagram in many ways.

In Liber de herbis et plantis an extensive, well-constructed herbal from the 1300s, we find a number of features that might have inspired Plant 35v. The vine twines around a host, there are clumps of dark-colored berries and, an important detail, the host has crenelated oak-like leaves. Plant 35v resembles the Liber de herbis diagram in many ways.

The ivy in Sloane 4016, a carefully drawn herbal from c. 1440, is presented in the same way as Liber de herbis except for the shape of the leaves and is probably copied from it or a source common to both.

The biggest difference between Plant 35r and the drawing in Liber de herbis, is that the VMS plant includes roots and does not include leaves. The other significant difference is double-vine twining from opposite directions around the host. Since it seems unlikely that the VM illustrator would concidentally use an oak-leaved host that is drawn so similarly to the one in Liber de herbis, we can surmise that he may have seen this drawing or one of the herbals it inspired.

Could the VMS Plant Have Been Independently Conceived?

The VMS Plant is difficult to identify without leaves or a label, so we don’t know for sure if it is Hedera. One could argue that the vine in the VMS might be one that is attracted to oak trees, as poison oak is in North America, but it follows the same conventions as the vines depicted in other European medieval herbals and they are all labeled Hedera (usually Hedera helix or Hedera nigra) and Hedera species are quite happy to climb any vertical surface that is near the young plant.

The VMS Plant is difficult to identify without leaves or a label, so we don’t know for sure if it is Hedera. One could argue that the vine in the VMS might be one that is attracted to oak trees, as poison oak is in North America, but it follows the same conventions as the vines depicted in other European medieval herbals and they are all labeled Hedera (usually Hedera helix or Hedera nigra) and Hedera species are quite happy to climb any vertical surface that is near the young plant.

Since Hedera is not parasitic, it can sink its hooks into almost any host, including a bare wall, and isn’t specifically attracted to oak trees. Thus, the choice of an oak-leaved host in the drawings is more likely to be based on herbal tradition than the propensity of the plant.

Herbal Tradition or Original Work?

Sloane 4016 (left) was created around 1440 and probably post-dates the Voynich Manuscript, but its forerunner Liber de herbis et plantis, probably predates the VMS by several decades.

If Liber de herbis influenced the VMS, it’s natural to ask where it was created.

It originated in the southern Holy Roman Empire in the region of Lombardy, land of the “long beards.” The kingdom of Lombardy went into decline but still stretched from the Piedmont region in the west to Austria in the east during the late 14th and early 15th centuries. Italy as we know it didn’t exist until the later 1800s. Some researchers have categorized herbals from this time and place as “northern Italian herbals” but I prefer to think of them as Lombardic.

Is Plant 35v intended to be a Hedera species? We don’t know. It’s noteworthy that Hedera has a darker more roughly-textured knob in the center of each berry such that light reflects more readily off the smoother surface around it. Could this account for the way the berries in the VMS are drawn with lighter rings around the edges?

Was the VMS influenced by Lombardic herbals? Possibly.

Based on extensive observation of the VMS document and its various drawings, I’m inclined to think the author of the VMS was a creative person who danced to a different drummer—either someone from a different culture who brought along a fresh viewpoint, or an individual with a unique way of seeing things. If the illustrator based the drawings, in part, on other herbals, it’s difficult to know for sure, as they have not been slavishly copied, and that is part of its attraction. If the drawings were standard copies of earlier work, there would be less of a mystery, and less to explore.

J.K. Petersen

——————————————————————————————————————-

Postscript, 12 Feb. 2016:

There is something I appear to have overlooked when I first wrote this article. I didn’t include the ivy drawing in Egerton 747 because I initially perceived it as a different style of drawing. It’s a twining example of Hedera nigra, but it doesn’t twine around an oak-like tree. Or does it?

Let’s look at the drawing more closely. You’ll notice that it’s two plants and that it’s twining around something that looks like an upright shrub with deeply serrated leaves. Some herbals show ivy twining around a bare trunk. In nature, Hedera will twine around almost anything. In this picture, the leaves of the host plant are quite small, which is why I initially assumed there was no relationship between Egerton 747 and the herbals that show a larger oak-like plant as the host.

Let’s look at the drawing more closely. You’ll notice that it’s two plants and that it’s twining around something that looks like an upright shrub with deeply serrated leaves. Some herbals show ivy twining around a bare trunk. In nature, Hedera will twine around almost anything. In this picture, the leaves of the host plant are quite small, which is why I initially assumed there was no relationship between Egerton 747 and the herbals that show a larger oak-like plant as the host.

Recently, I realized that a later artist might interpret the deeply serrated leaves as crenelated leaves and may have morphed the concept in Egerton 747 into the oak-like tree in the other herbals, especially if the artist lived in an area with oak trees.

Egerton 747 is one of the early herbals, thought to have been created between c. 1280 and c. 1310 for use as a physician’s reference, and is known to have influenced some of the later herbals. Whether it influenced the style of drawing that led to the oak-like leaves is difficult to know, but the possibility should be considered and perhaps the text that accompanies some of the illustrations can help sort it all out.

© Copyright 2013 & 2016 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved