Please note. This blog was originally posted July 19, 2013, and I immediately removed it and inserted a placeholder because I thought to myself, “Am I giving too much away? Will this help someone else solve the VMS before I have a chance to solve it?” It took a few years to acknowledge that the VMS was going to be much harder to decipher than I assumed and might even require a coordinated effort among researchers, so I have enlarged a couple of the drawings, updated the fonts, and posted it again.

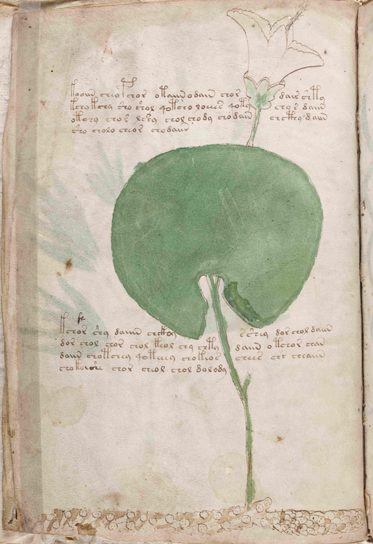

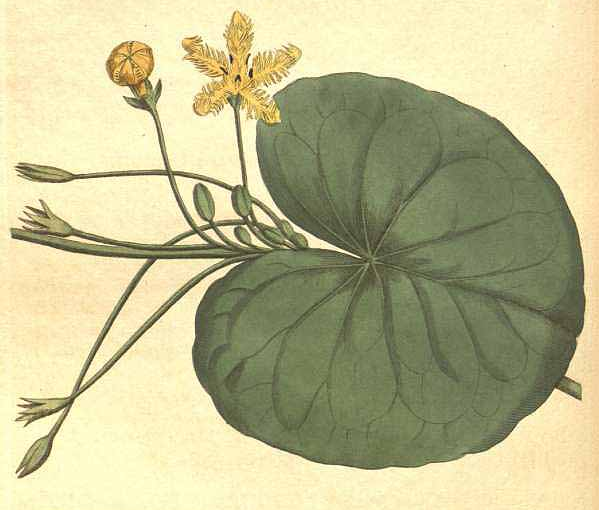

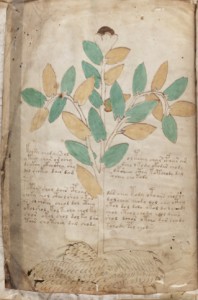

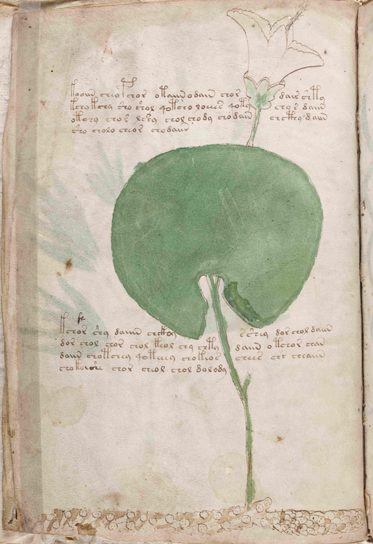

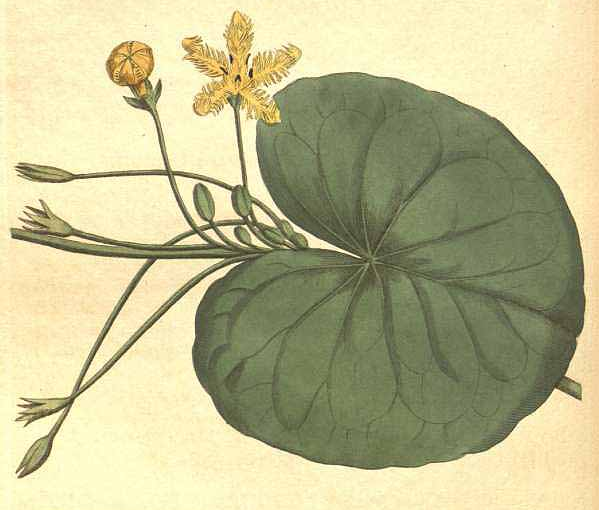

This is the image that started it all—the drawing that hooked me on the VMS… Folio 2v appears at first glance to be some kind of aquatic plant with a fringed flower, and it shows not only a leaf and flower, but the side-growing root, as well.

I‘m interested in plants, and I had never seen such an amazing drawing of a side-growing root (called a “rhizome”) in a medieval manuscript. It’s not only an excellent portrayal at a time when accuracy took second place to tradition, but holds some important clues to how the drawings are composed and where the plant might have originated.

I‘m interested in plants, and I had never seen such an amazing drawing of a side-growing root (called a “rhizome”) in a medieval manuscript. It’s not only an excellent portrayal at a time when accuracy took second place to tradition, but holds some important clues to how the drawings are composed and where the plant might have originated.

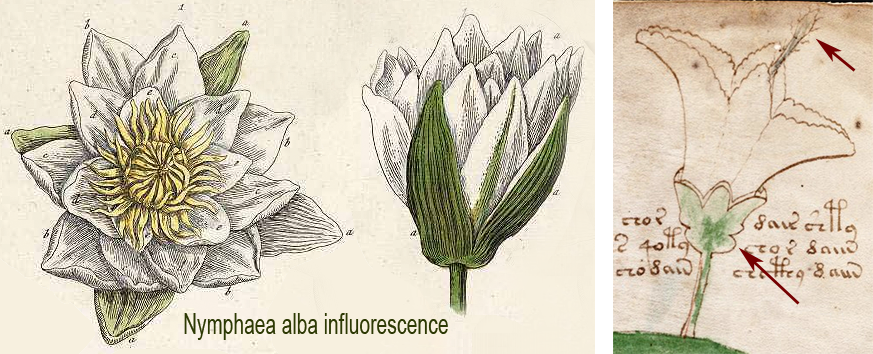

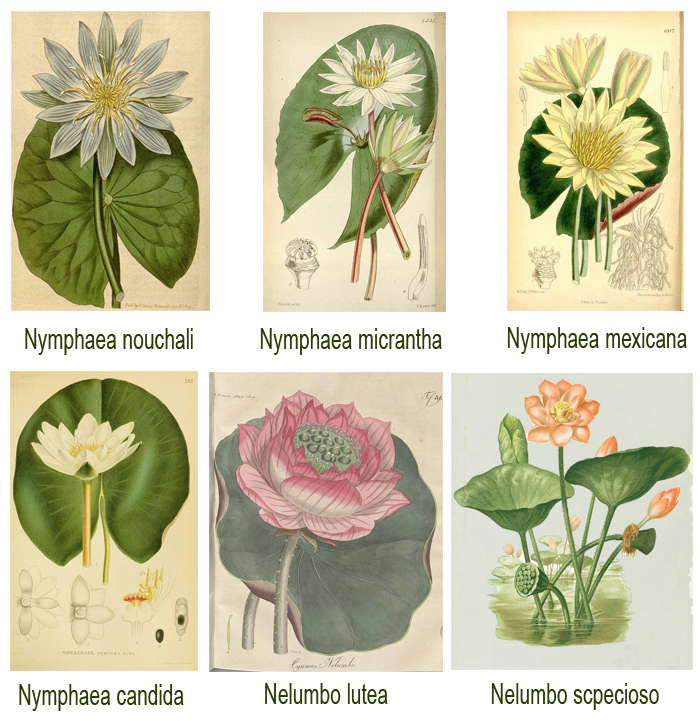

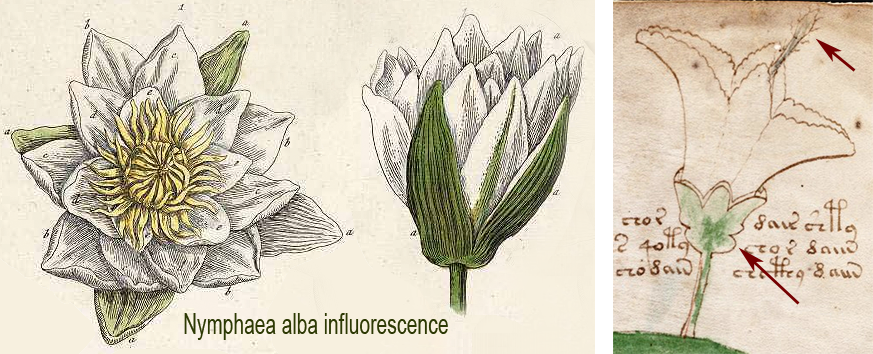

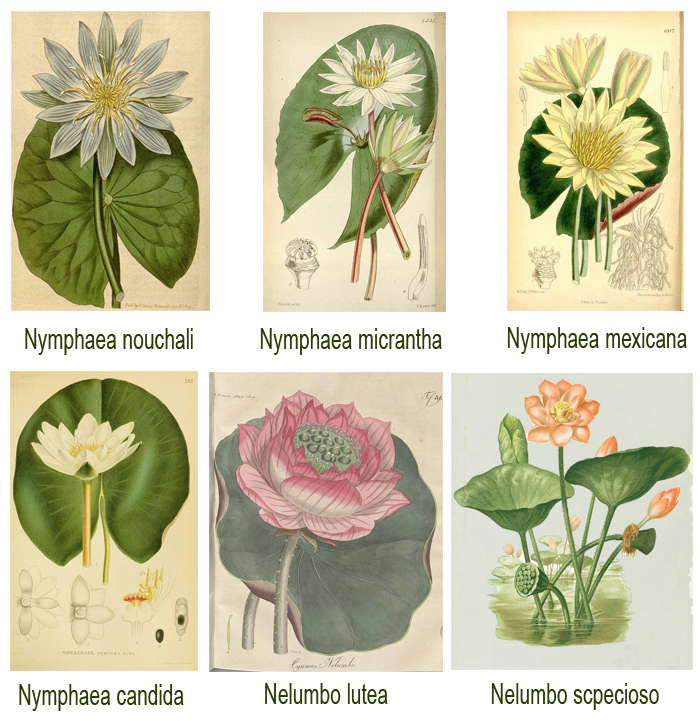

But I was perplexed because 2v didn’t have a typical water lily flower. The pistil is long and hirsute, there are only four petals, and they are fringed. Also, the calyx is stubby and indented. Obviously it wasn’t Nymphaeaceae, a family common to Eurasia and Africa, but due to the accuracy of the rhizome, I assumed there must be other wetland plants that would match the flower more closely. So, late in 2007, I started scouring the Web for a match.

Why look for wetland plants? Because this kind of rhizome is not practical for a land-dwelling plant that has to push its way through soil. There are many terrestrial plants with rhizomes, and even some with leaf scars (such as Solomon’s seal), but very few plants outside of aquatic, coastal, or swampy environments have this specific form of rhizome.

If the Voynich Manuscript did not have this drawing, my interest would probably have fizzled by 2009. Fantasy plants or poorly drawn plants don’t offer much help in deciphering cryptic text. There are other recognizable plants in the VMS, including viola and salsify, and possibly ricinus and cannabis, but they are common plants and less helpful in determining origin. Assuming the text is related to the drawings, identifying 2v might be useful.

So how does one interpret this drawing?

Dissecting the VMS Plant

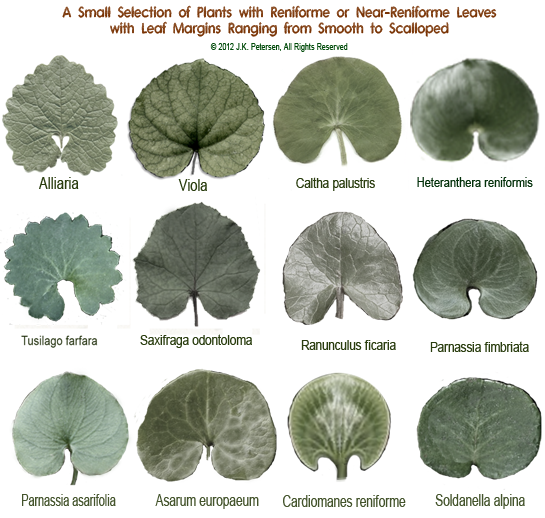

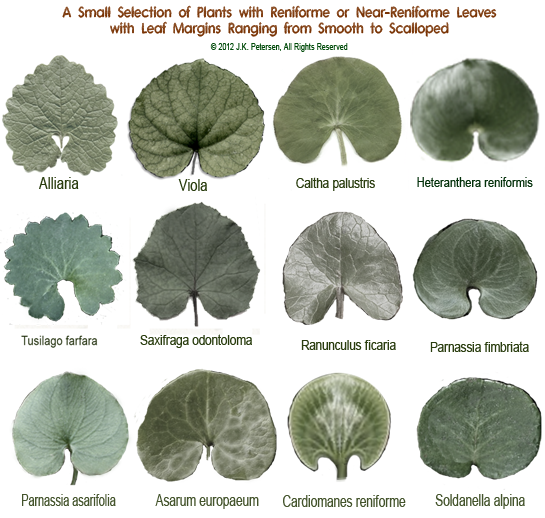

Let’s start with the leaf, since that’s what most people recognize. With most plants, the root is hidden, and the flowers of wetland plants can be quite variable, but kidney-shaped leaves (called “reniforme”) are distinctive enough to catch one’s attention.

Reniforme leaves can be smooth, serrated, or elegantly scalloped. Some have deep indentations where the stem attaches to the leaf, others have narrow or rounded indentations. Here are some examples:

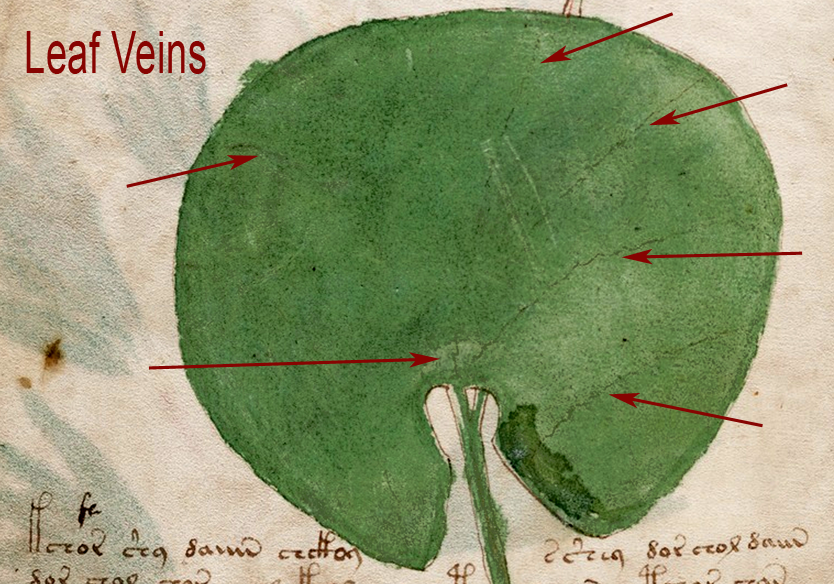

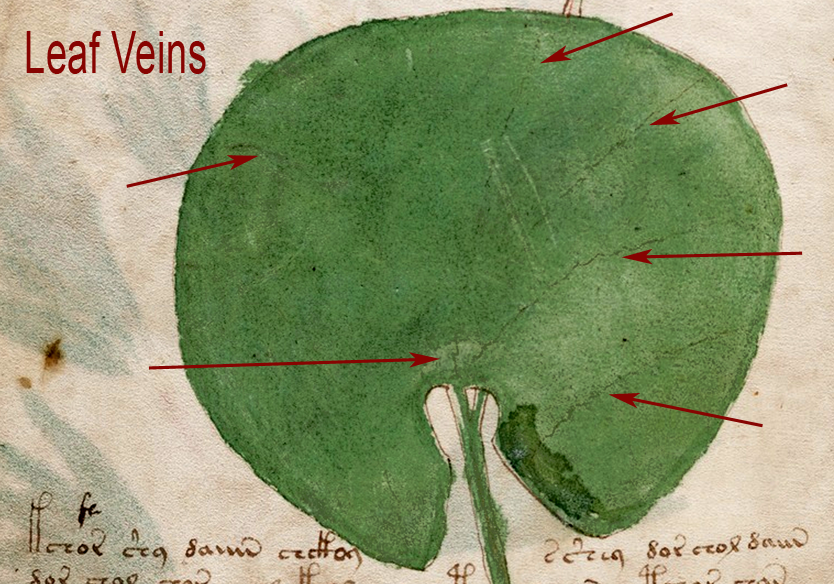

Notice the different patterns in the veins. The primary veins originate at the deepest part of the indentation, but flow out differently, depending on the species. Some are straight, some rounded, some arch back in toward the top.

The 2v veins have been lightly sketched with wiggly lines running to the outer margin. I have added arrows to make them easier to see. The lower-right vein seems out of place—it runs from margin to margin rather than starting in the center and there’s something tentative about the veins—there’s not enough detail to trust their accuracy, but the way they arc is closer to Soldanella or Caltha palustris than most other reniforme plants :

Note that the indentation where the stem attaches to the leaf is distinctly rounded, similar to Heteranthera, Parnassia, and Asarum. This shape is not characteristic of Nymphaea species, which usually have V-shaped indentations, or Nelumbo, which is typically round, with the stem attaching near the center:

So what kind of plant is 2v?

There are about two hundred commonly known species with reniforme leaves and about two-thirds of these have smooth margins. They range in size from delicate thumb-sized alpine snowbells, miniature honey-suckles, and tropical Geophilas, to water lilies so large, they can support the weight of a child. There are even spore-bearing ferns with kidney-shaped leaves.

The VMS Root

Many reniforme plants spread through rhizomes. The root inches sideways, under water or soil (usually moist soil), to send up new shoots at a distance from the old plant. As the old leaves fall off, a pattern of scars is left behind. Since there is less soil to impede them, aquatic plants may have rhizomes that are many meters long.

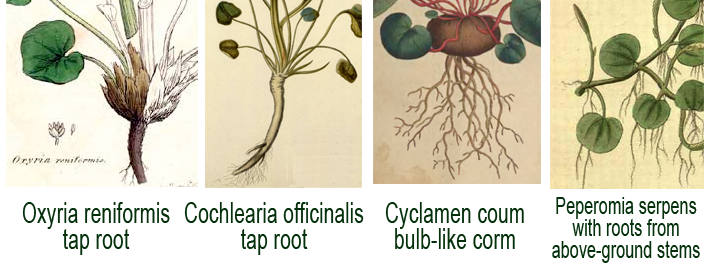

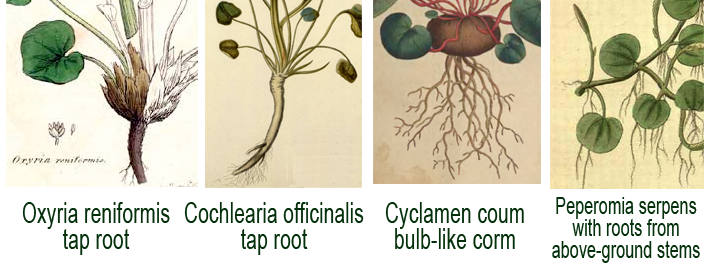

Some plants, like Cochlearia officinalis, Cyclamen, and Oxyria reniformis have tap roots, corms, tendrils (like buttercup), or runners that spread above ground rather than beneath ground or water, so there isn’t one kind of root specific to reniforme plants, as these examples illustrate:

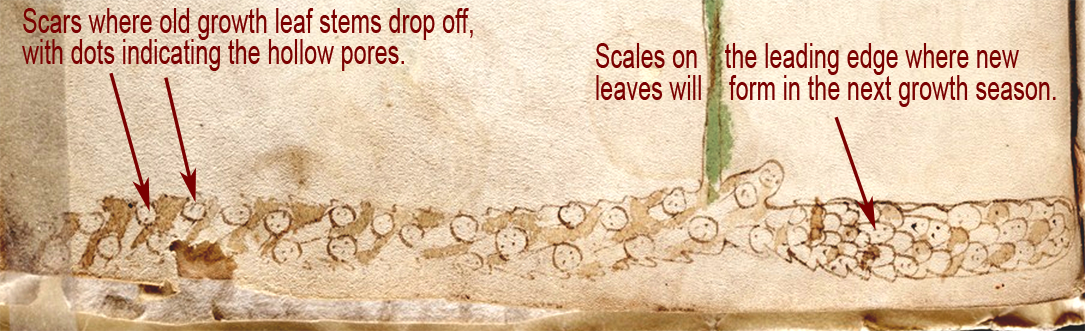

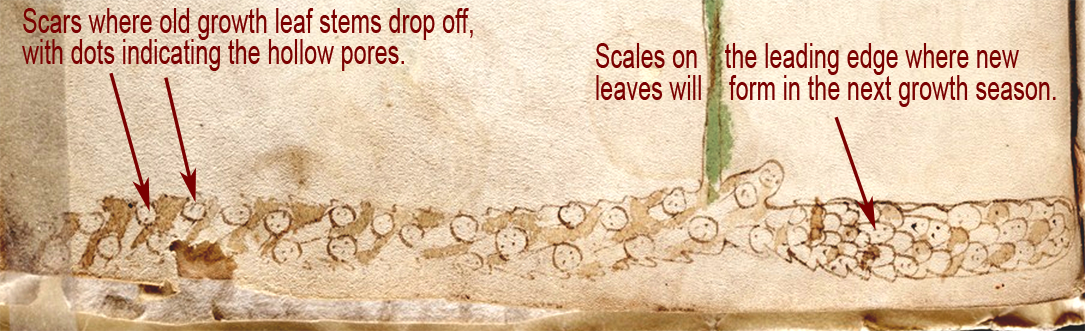

The VMS rhizome is not professionally drawn, but it’s pretty good—there’s an effort to document important structures ignored by other botanical illustrators. Note the series of nubs to the left, where the the old stems dropped off, with dots to indicate the vascular pores. The scaly growth with a rounded head, to the right, is where new leaves will emerge in the next growing season. Plants with this form of rhizome don’t always have a scaly root-cap on the leading edge, which helps to narrow down possible IDs for this plant.

Even though the leaf and flower don’t match 2v, the roots of some Nymphaea species are similar to the VMS. In the following images, note how the two roots have different shapes and patterns of leaf scars. As the leaves die out, they resemble fossils from Jurassic Park (right):

Even though the leaf and flower don’t match 2v, the roots of some Nymphaea species are similar to the VMS. In the following images, note how the two roots have different shapes and patterns of leaf scars. As the leaves die out, they resemble fossils from Jurassic Park (right):

There are a number of species with leaves and flowers that look like 2v. Some of these also have similar roots:

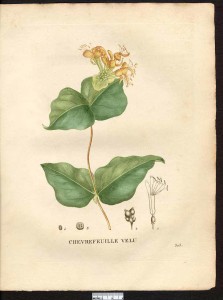

Nymphoides peltata, a Eurasian plant, has fringed yellow flowers and reniforme leaves, but the calyx has slender points, and the pistils are not typically long. Villarsia nymphoides, the fringed water lily, is a European species very similar to Nymphoides peltata. Villarsia reniformis, an Australian plant, is similar as well, and often has an extended pistil. The leaves will sometimes stand up in much the same manner as the VMS drawing.

Nymphoides peltata, a Eurasian plant, has fringed yellow flowers and reniforme leaves, but the calyx has slender points, and the pistils are not typically long. Villarsia nymphoides, the fringed water lily, is a European species very similar to Nymphoides peltata. Villarsia reniformis, an Australian plant, is similar as well, and often has an extended pistil. The leaves will sometimes stand up in much the same manner as the VMS drawing.- Nymphoides aquatica, a North American plant, matches quite well. It has white, slightly fringed flowers, reniforme leaves (although not as indented as the VMS plant), and distinctive white leaf-scar nubs at the base of the plant. It’s a small plant and the “bananas” that dangle from the base are much more noticeable than the scars, but it does produce a horizontal root.

- Nymphoides indica, an Asian plant known as the water snowflake, is similar as well, with white flowers that range from lightly to heavily fringed, and which sometimes have an extended pistil that becomes more visible as the petals spread. In most respects, it is a good match but it’s very difficult to determine from online images if the root has a leading cap like the VMS plant and, like the other Nymphoides, the calyx is slender and pointed.

- The New World counterpart to Nymphides indica is Villarsia humboldtiana, and it resembles the VMS plant in many respects. It has white fringed flowers, with an extended pistil, reniforme leaves, and a rhizome similar to N. indica. In fact, it was first thought they might be the same species. N. humboldtiana grows in the North American Gulf region.

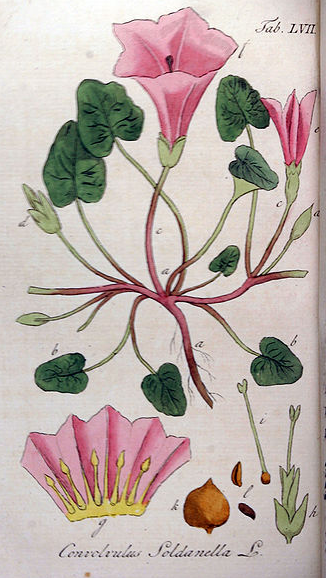

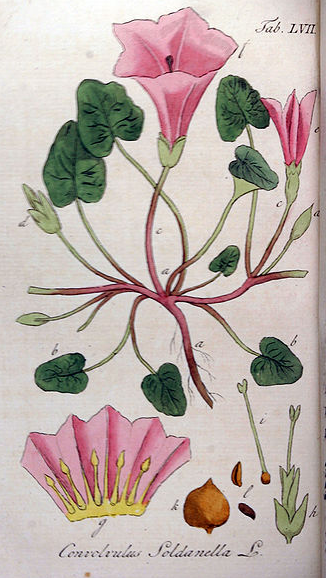

There are terrestrial plants that are smilar, as well. Examples include Parnassia fimbriata, a wetland plant with lightly fringed white petals, an extended style, and reniforme leaves, and Calystegia soldanella (right), a coastal plant with an extended pistil, slightly ruffled petals, and running rhizomes. Also Asarum europaeum, which has reniforme leaves and extensive rhizomes, although the flower looks more like a jug. Even some species of Malva bear similarities to the flowers and the leaf, but the rhizome is not a good match. Very few terrestrial plants include these traits together with a rhizome with leaf scars that match as closely as water-loving plants.

There are terrestrial plants that are smilar, as well. Examples include Parnassia fimbriata, a wetland plant with lightly fringed white petals, an extended style, and reniforme leaves, and Calystegia soldanella (right), a coastal plant with an extended pistil, slightly ruffled petals, and running rhizomes. Also Asarum europaeum, which has reniforme leaves and extensive rhizomes, although the flower looks more like a jug. Even some species of Malva bear similarities to the flowers and the leaf, but the rhizome is not a good match. Very few terrestrial plants include these traits together with a rhizome with leaf scars that match as closely as water-loving plants.

Thus, the small aquatic and semi-aquatic plants variously known as Nymphoides/Villarsia/Menyanthes/Ornduffia match well to most aspects of the VMS plant, depending on the species. They differ in that the calyx tends to be a little longer and more pointed than Plant 2v, there are five petals rather than 4, and not all species have an extended pistil/style or significant leaf scars, but some do. This category of plants is native to Asia/Malaysia, Australia, Europe, parts of Africa, and the Americas, so there are many possible origins.

Summary

It’s difficult to pinpoint a species without detailed images of the rhizomes, and very few are currently documented online, but perhaps in time they will become available so that tentative identifications of Plant 2r can be confirmed or denied. One thing is certain however—if all parts of the plant are taken into consideration, the VMS plant matches floating hearts and their cousins (and even Calystegia soldanella) much more closely than the larger Nymphaeas and Nelumbos that we typically associate with the term “water lily”.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2013 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved