Stylistic Variations

Medieval scribes were copyists. Before the invention of the printing press, it was difficult to mass-produce text other than by carving woodblocks or creating ceramic molds that could be impressed into wax or clay, both of which were inefficient, laborious processes for texts of more than a few pages. So they copied by hand, one letter at a time.

Many of the copied manuscripts were sacred texts and it was considered sacrilege to alter the wording. Exact copies were encouraged and in some cases required by cultural law (as in the Hebrew Torah).

Since the idea was to reproduce the book as closely as possible, not to create an original composition, the basic template was often the same and regional patterns can be recognized, some of which can help us trace the origins of a manuscript.

That’s not to say there was no room for originality. Often the text was accompanied by embellished initials or illustrations, and variations were introduced by some of the more creative (or rebellious) individuals, variations that were then copied by subsequent generations.

Copying Zodiac Symbols

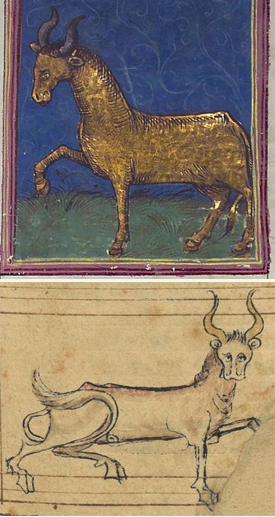

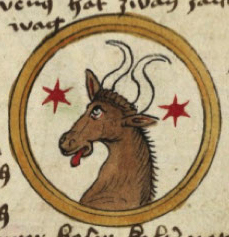

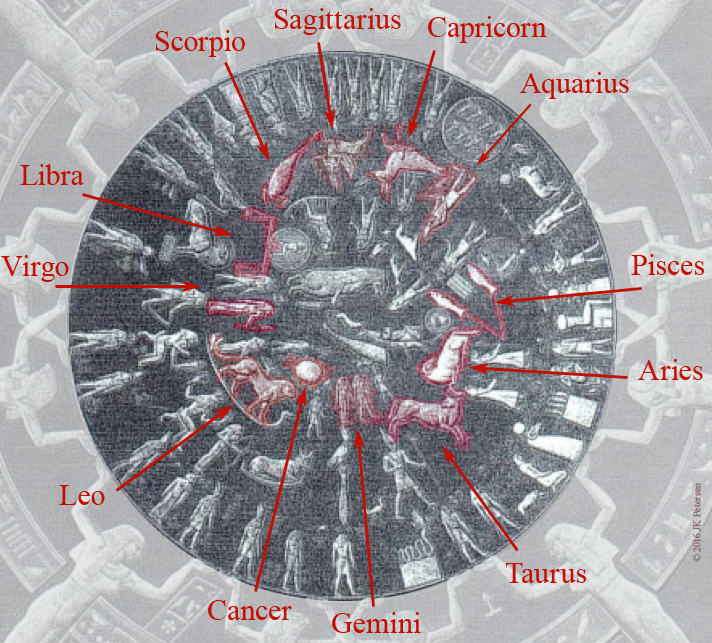

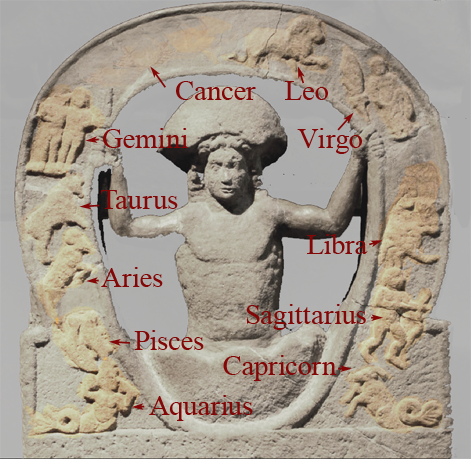

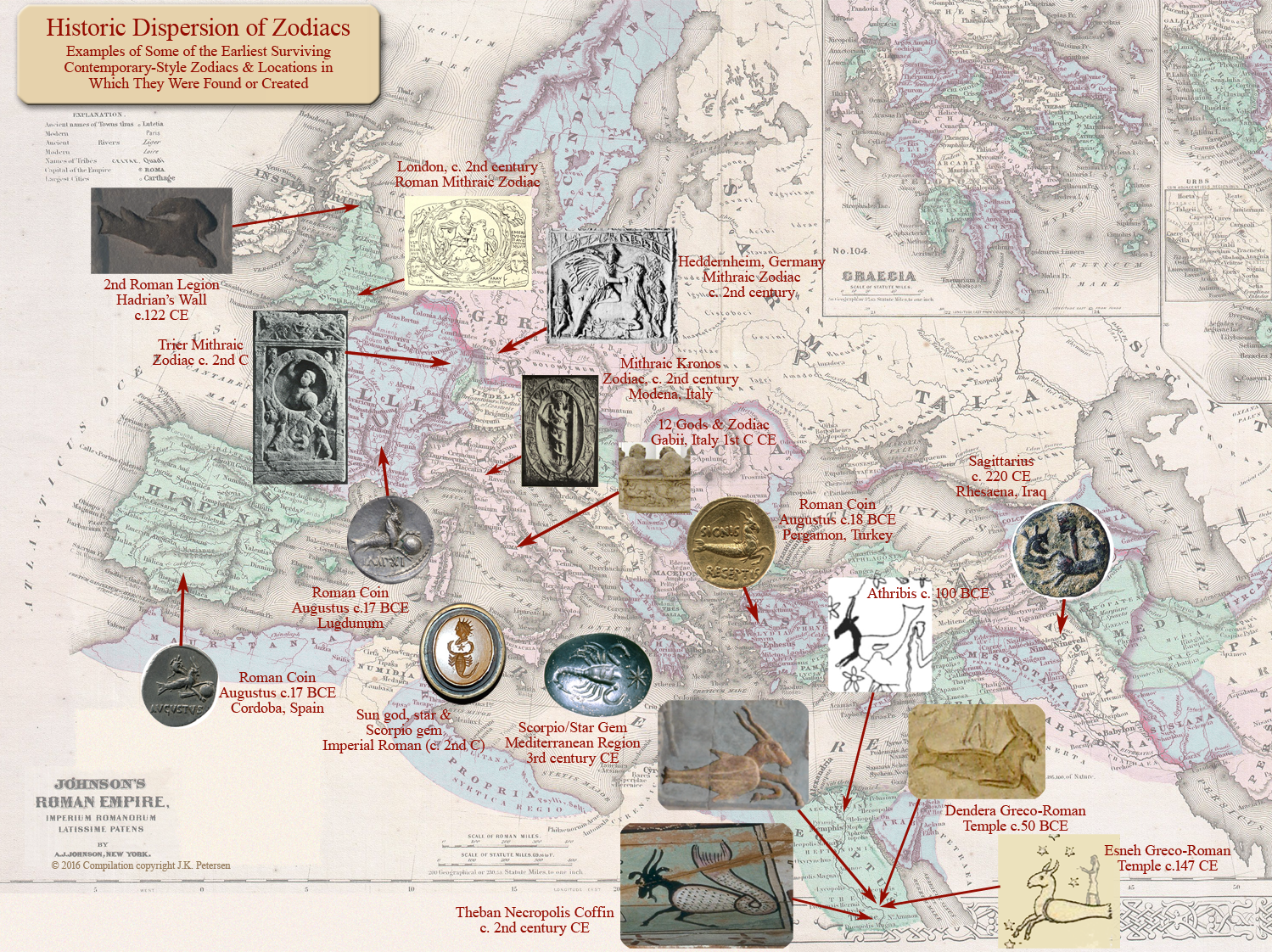

Drawings offered a little more leeway for artistic expression than the text. Over the centuries, zodiac symbols have been drawn or sculpted with small variations that point to certain regions or illustrative traditions. Ancient zodiacal figures, based on Pagan or Mithraic beliefs (which were broadly disseminated by Roman soldiers), often depicted figures as nude or dressed in scanty togas, while those from the late middle ages more often were clothed.

Drawings offered a little more leeway for artistic expression than the text. Over the centuries, zodiac symbols have been drawn or sculpted with small variations that point to certain regions or illustrative traditions. Ancient zodiacal figures, based on Pagan or Mithraic beliefs (which were broadly disseminated by Roman soldiers), often depicted figures as nude or dressed in scanty togas, while those from the late middle ages more often were clothed.

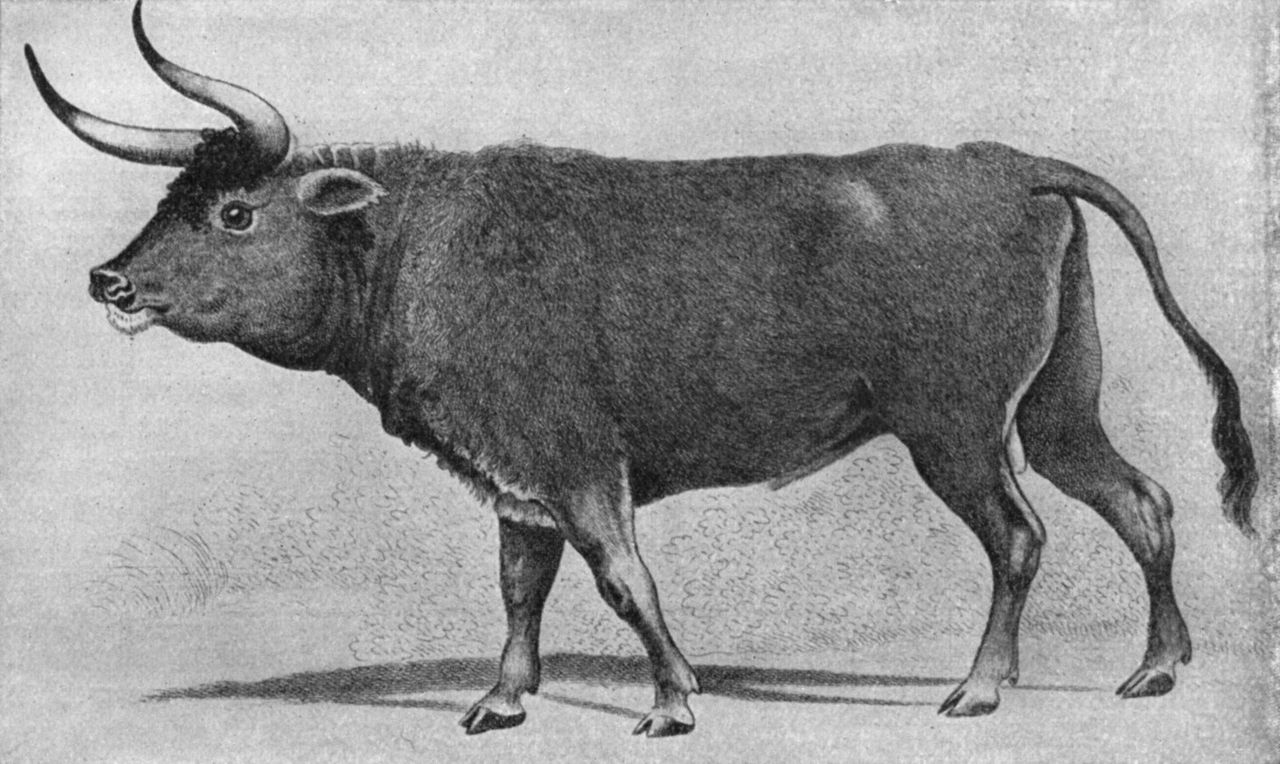

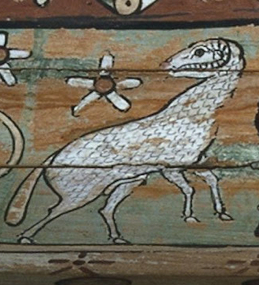

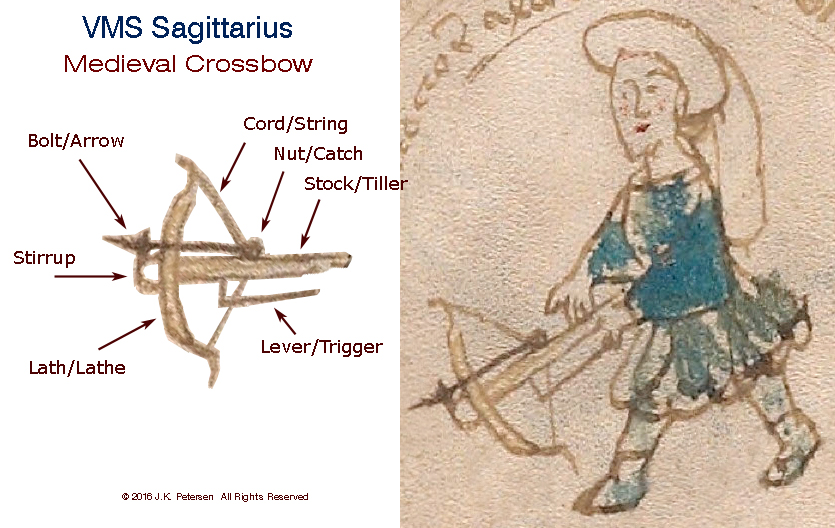

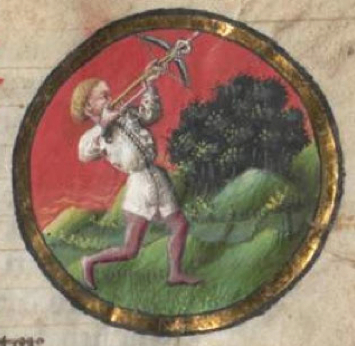

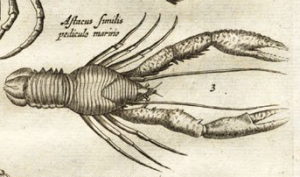

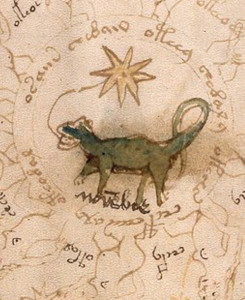

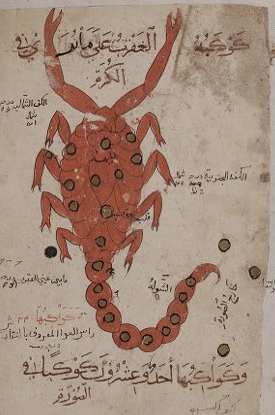

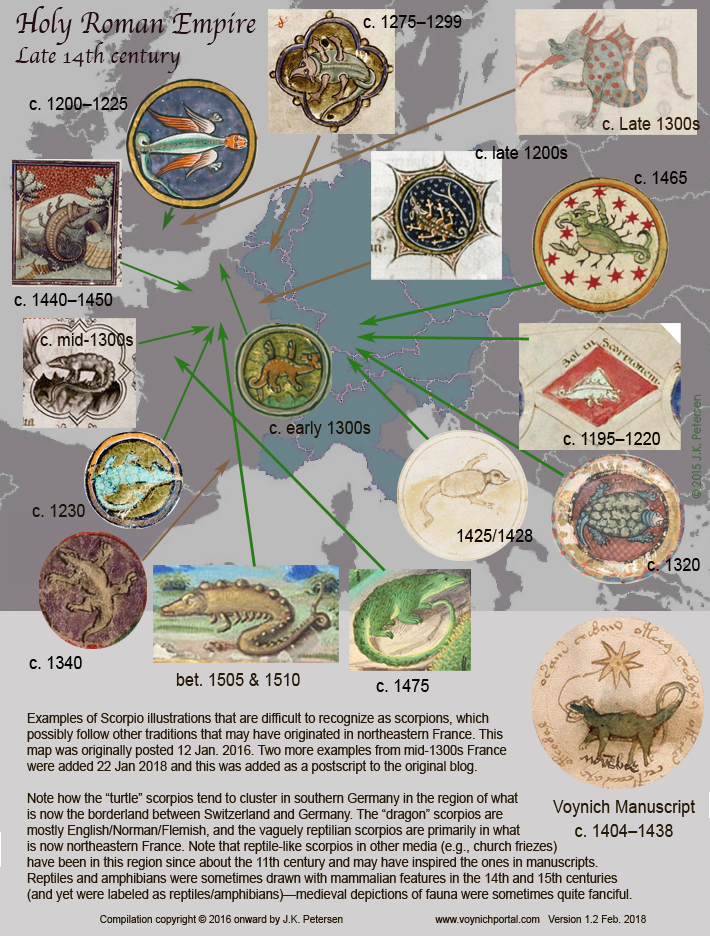

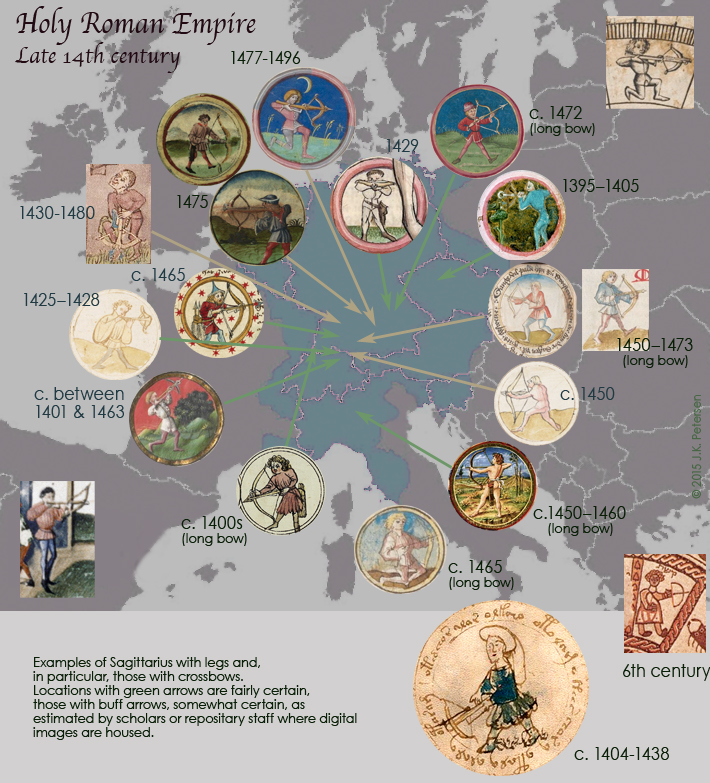

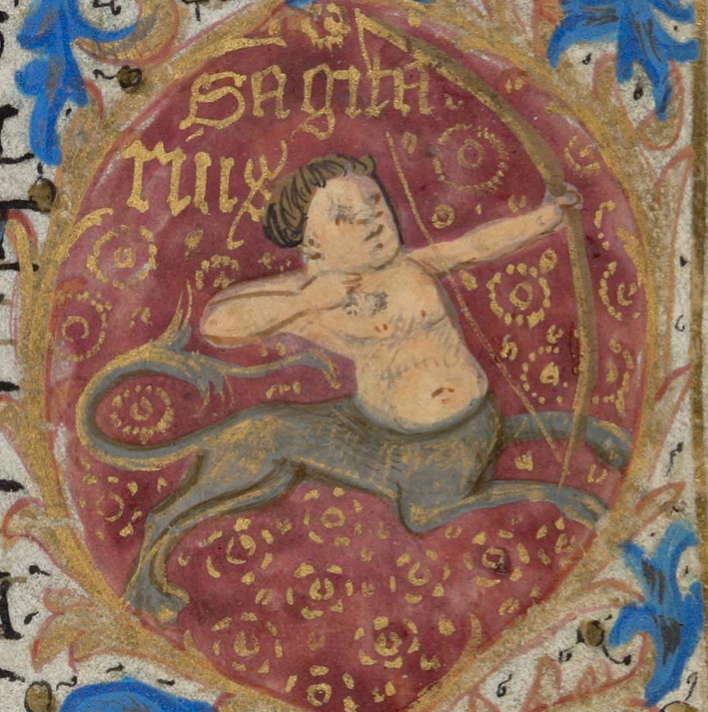

Animal symbols underwent small changes, as well. Capricorn started out as a seagoat with a distinctive fish-tail, and gradually took on a variety of forms, including goats in shells, goats with dragon tails, or a naturalistic goat with four legs. Cancer could be a crab, crayfish, or lobster. Scorpio was originally a scorpion but was later shown in some areas as a lizard or dragon. Sagittarius could be a centaur, satyr, or human figure.

Tracing the Traditions

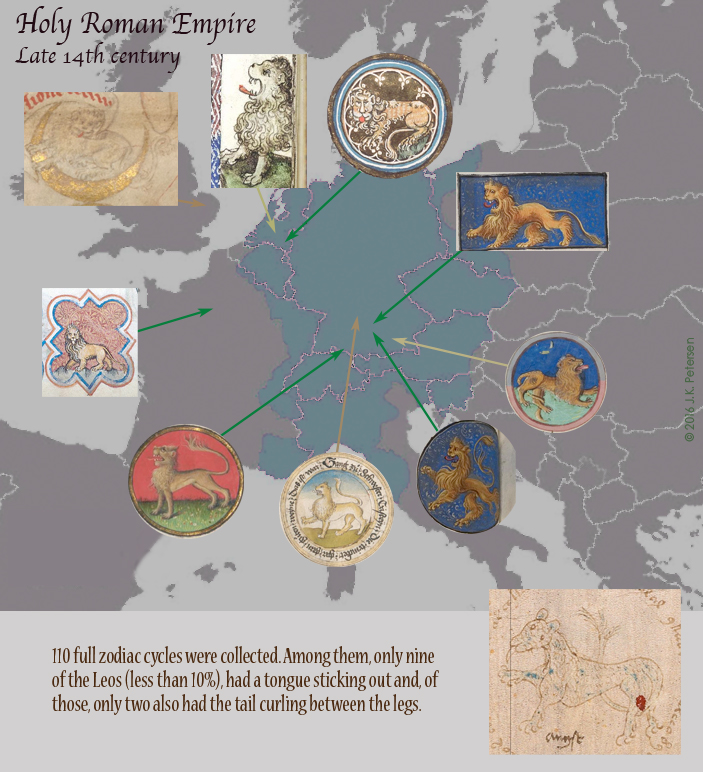

Over a period of several years, I collected hundreds of examples of zodiac cycles. Almost 400 of them were western-style zodiacs (most of them full cycles with 12 signs). After comparing them for stylistic patterns and trends, I was surprised to notice a change in the depiction of Libra in the early 12th century that I haven’t seen others remark upon but which may tell us something about the VMS.

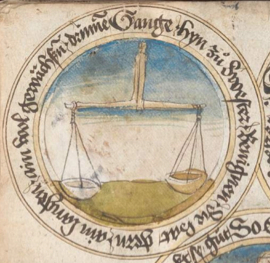

Libra in Hand

Prior to the 12th century, Libran scales were usually held in the hand of a human figure, except in a few instances where space was very constrained. There are a number of exceptions where the scales are shown alone, including

- a Roman mosaic in Tunis

- the 9th century Leiden Aratea zodiac, and

- an 11th century mosaic in Otranto Cathedral (south of Brindisi, Italy).

But these are exceptions rather than the rule—scales-only Libras are less common than those where the scales are held by a human or human-like figure (usually a Roman god), as will be seen from examples that follow.

Exploring the Imagery

Male Libra holds scales aloft in this Carolingian zodiac from the Reichenau monastery, Germany. Image courtesy of the Vatican Library.

Prior to the 12th century, most treatises on astronomy and astrology were not illustrated, but there are some and they derived from Greco-Roman styles.

The painting on the right is from a Carolingian manuscript, illuminated at the largest scriptorium in S.W. Germany. The face has been damaged, but based on the clothing treatment of other figures in the cycle, the figure holding the scales appears to be male. This example illustrates that the figure-with-scales imagery was in use in central European manuscripts by the 9th or early 10th century, but that local styles of dress had not yet been incorporated into zodiac drawings.

About 200 years later, something changed and that change appears to center around southwest Germany.

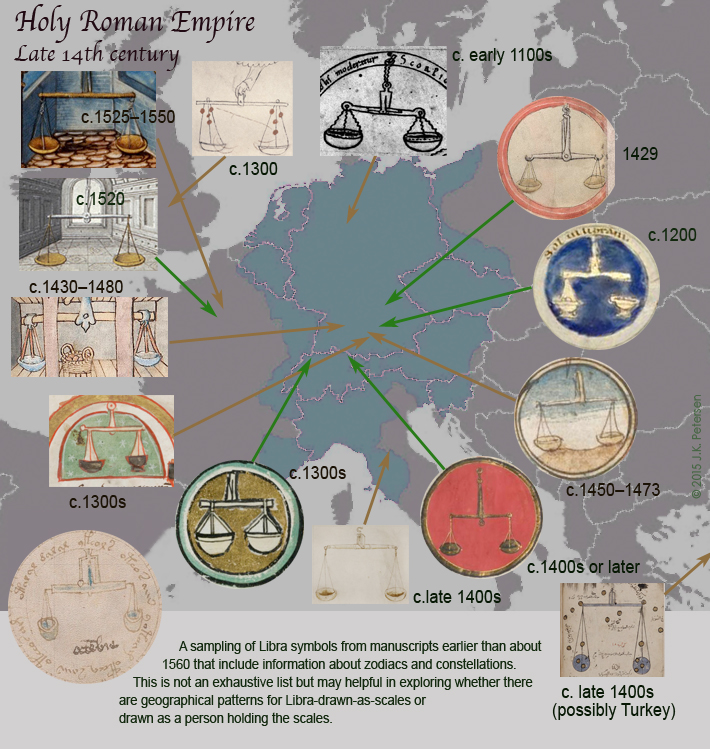

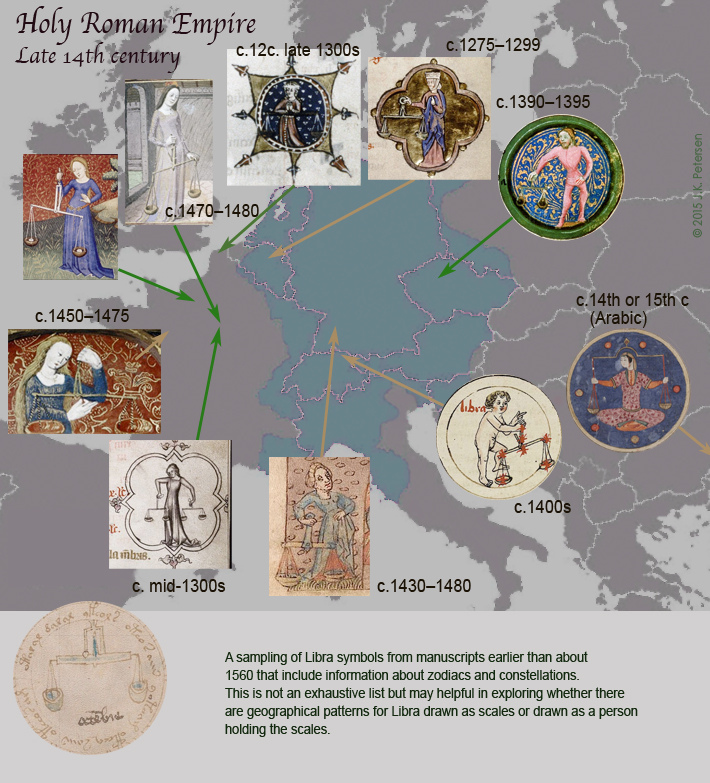

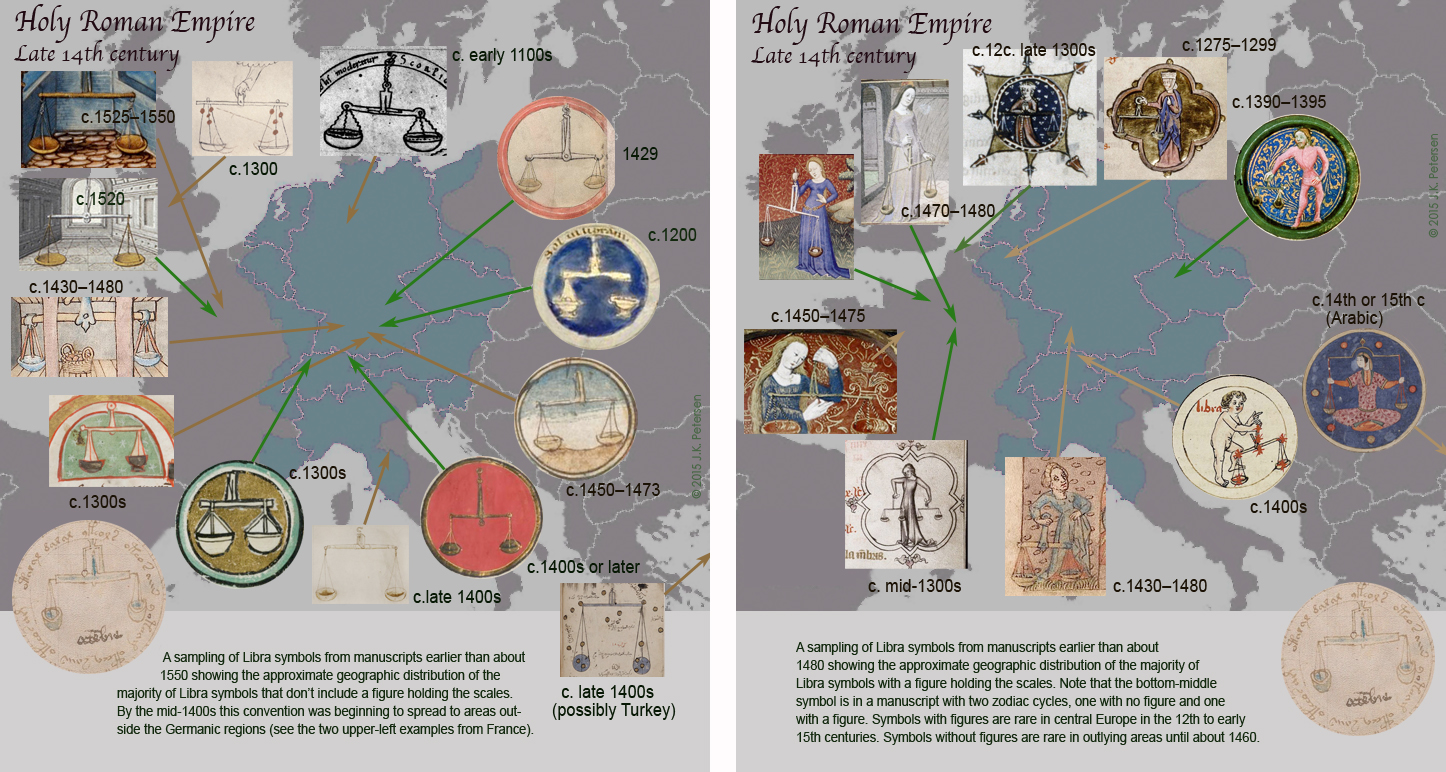

What stands out after comparing hundreds of sets of pre-1500 zodiacs is a temporal and geographic cluster of Germanic zodiac signs that depict the scales alone (mostly in missals and psalters but also in medical and astrological texts). There is also a 13th-century zodiac from Georgia without a figure that could be an isolated example or which might be related in some as-yet undetermined way to the others that I have included in the diagram below.

In the following chart, I have grouped the images according to whether Libra includes a figure (top) or only the scales (bottom). It is further organized according to approximate date of creation (exact dates are not known but are probably correct within about 10 to 70 years):

I thought I had found a 12th-century example of scales without a figure in the Soissons Cathedral stained-glass windows but then discovered that most of the glass had been replaced in the late 1800s.

I thought I had found a 12th-century example of scales without a figure in the Soissons Cathedral stained-glass windows but then discovered that most of the glass had been replaced in the late 1800s.

[Addendum: I forgot to post this map that accompanies the above chart, which shows a sampling of the approximate temporal/geographical distribution of these symbols. I include it now (May 7, 2016)]

As with most research, the above chart, assembled over several years, is still a work-in-progress. Nevertheless, some interesting patterns are apparent between approx. 1130 and 1460:

As with most research, the above chart, assembled over several years, is still a work-in-progress. Nevertheless, some interesting patterns are apparent between approx. 1130 and 1460:

- Most zodiacs signs were enclosed by circles unless they were a spoke in a zodiac “wheel”. A few were on plain backgrounds. By the 15th century, some were becoming more elaborate, especially those from France.

- Zodiacs in Frankish and English manuscripts typically feature a figure holding the scales (Trinity B-11-5 from Normandy is an exception to this general pattern) until around 1460.

- The figures holding the scales are usually standing, except those from Persia and possibly Armenia, which are usually sitting cross-legged.

- Libra images in traditional Roman garb are usually male. Others are usually female.

- By the mid-13th century, most of the zodiacs are drawn with medieval dress rather than Roman togas.

- Ancient Roman zodiacs were often created in tile or stone, but Carolingian-era and early-medieval zodiacs from English and Germanic regions (Germany, Switzerland, Austria and northern Italy) showed up frequently in manuscripts, whereas Frankish zodiacs tended to embellish physical structures such as churches (stone-carved portals and stained-glass windows were popular).

- Before 1455, scales without figures were mostly Germanic.

- Simple versions of scales without figures don’t show up with any regularity in England, Italy, or France until about 1260, and even then they were a distinct minority compared to those with figures.

The Missing Link

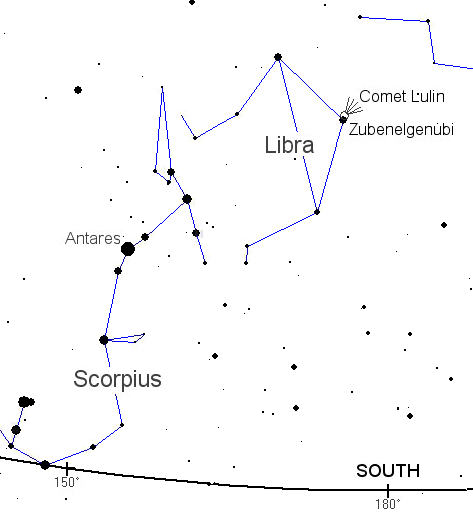

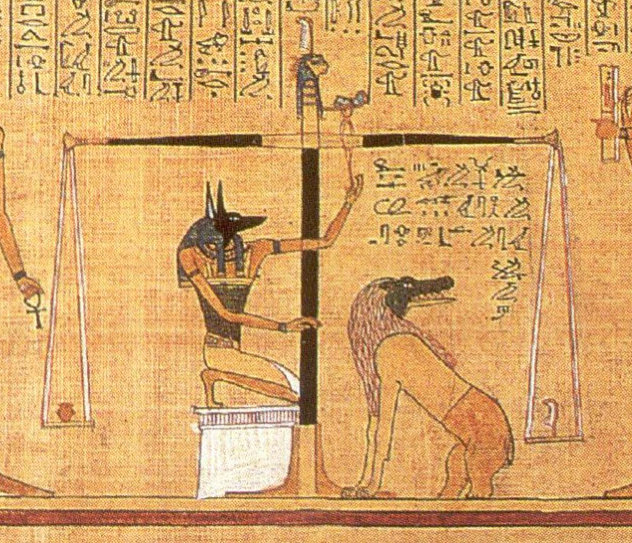

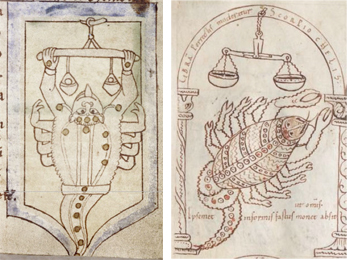

In Bodley Ms 614 and Digby 83 (both English manuscripts), a scorpion (rather than a human figure) holds the scales. In the German version (right) the scorpion is close to the scales but doesn’t hold them, which may have led copyists to assume the scales and scorpion were completely separate.

I searched extensively through zodiacs to discover a reason for the simplified Libra and finally had enough examples to guess what may have happened. Ancient depictions of Libra sometimes show the scales held by a scorpion rather than by Virgo.

The examples on the right serve as a tentative explanation. The one with a scorpion holding the scales is from England from c. 1150. The one on the right is from S.W. Germany from around the same time. They both derive from the Hyginus tradition (which traces back to Greek sources before the 2nd century CE), but the second one visually separates the scorpion from the scales. Since Scorpio is a constellation in its own right, copyists may have overlooked or dismissed the association between Scorpio and Libra and further separated the scales from the Scorpion in subsequent copies, thus creating a stand-alone Libra that was particularly prevalent in Germany.

The Spread of the Illustrative Tradition

The simplified scales in the Germanic manuscripts are not due to lack of space—the images of Sagittarius and Aquarius in the same zodiac cycles are quite detailed—so it appears to be a stylistic choice that contrasted with that of surrounding regions.

The simplified scales in the Germanic manuscripts are not due to lack of space—the images of Sagittarius and Aquarius in the same zodiac cycles are quite detailed—so it appears to be a stylistic choice that contrasted with that of surrounding regions.

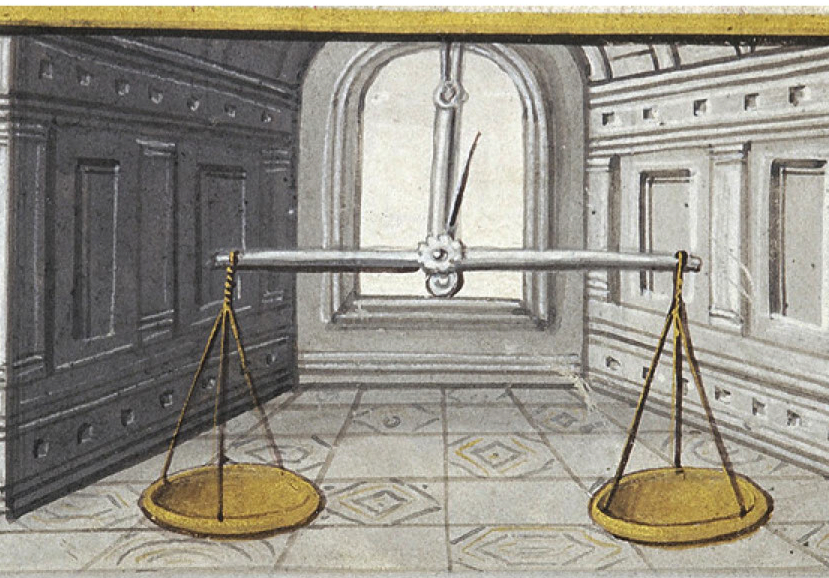

By the second half of the 15th century, it is apparent that figureless scales had spread to other countries, as in this example from France from c. 1457 (right). The French zodiac cycles (which were sometimes painted by Flemish artists) tended to be more ornate and more richly colored than earlier Germanic Libras and were often shown within architectural settings, an innovation that set them apart from the Germanic examples.

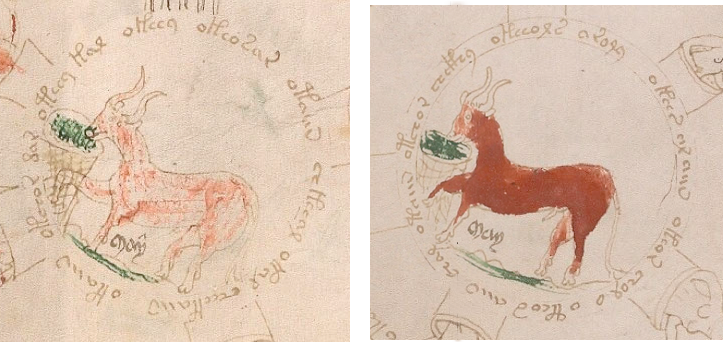

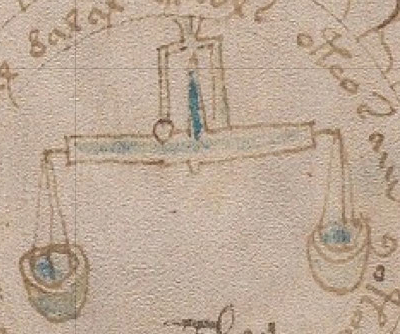

Simplified Libra and the Voynich Manuscript

The Voynich Libra most closely resembles the Germanic zodiacs, regardless of whether this was coincidental or deliberate. It doesn’t look like conventional Libras from France (with the exception of few isolated examples from NE France or Flanders) or from the eastern Mediterranean. It particularly resembles those from Switzerland, southern Germany, eastern Austria, and England (note that England had strong ties with St. Gall at the time).

This by itself doesn’t prove an association, but taken together with Cancer as a crayfish, Scorpio as a lizard or dragon, and Sagittarius with legs and a crossbow (which is a rare combination), there are multiple illustrative choices that point to the same region.

Summary

A German Libra from c. 1460s probably post-dates the VMS but I’ve included it here because it is a rare example of a zodiac with text written around the sign in a circle (BSB CGM 312).

There may not be an exact model from which the VMS was copied (if there is, it may not be publicly accessible or may have perished along the way). It’s entirely possible that the VMS illustrator was exposed to a variety of styles if a manuscript library or scriptorium were nearby, or if his profession involved travel.

If the illustrator researched multiple sources and then filled in the blanks with original ideas, the Voynich Manuscript’s association with other documents may never be clear, but the examples in the above chart show that this style of Libra was particularly prevalent in central Europe from about the early 12th century to the 15th century, which includes the period during which the VMS was created.

It hasn’t been determined where the VMS illustrator was born or lived, but it appears that he or she was influenced, at least in part, by documents from central Europe.

J.K. Petersen

© Copyright 2016 J.K. Petersen, All Rights Reserved